|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

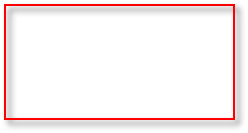

Almost a mirror-image of the illustration of French revelers in front of one of

the looted European-style palaces that appeared in L’Illustration, this print was done by G. C. de Fortavion, an artist who

accompanied the French high command in China in 1860.

(full image and detail highlighted in red)

[ymy7102]

|

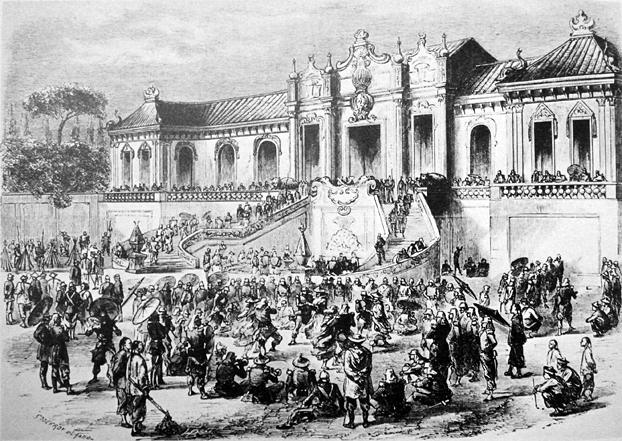

This vivid illustration from a French memoir published by Armand Lucy in 1860

depicts a French soldier leading on a leash a mustachioed Chinese “peasant” who carries a halberd, dwarfs him in height, and carries various items taken

from the Yuanmingyuan on his back. The soldier carries a parasol in one hand

and a fan in the other. His booty includes, remarkably, a bird in a cage.

Caption under the drawing:

“Cela s'appelle: ENTREPRISE DE DÉMÉNAGEMENTS CHAUVIN ET Cie, POUR LA CAMPAGNE ET L'ÉTRANGER.” (translation: “This is called: Business and Removal Chauvin and Co., Campaign and Abroad.”)

[8161_113_Armand_Lucy_gb135] Google Books |

PLUNDERING PARADISE

The plunder that took place before the burning of the palaces was perhaps even

more shocking than the destruction of the buildings themselves. The British

said that the first round of “plunder and wanton destruction” was the work of the French. Soon, however, the British did more than their share. They ransacked

each building, appropriating the contents of the private quarters and

public rooms. Great amounts of gold, furs, robes, silks, jades,

porcelains, and statues were taken, as well as Western clocks and ornaments—gifts of the 1793 Macartney mission, or from European contacts

of earlier eras. Much was destroyed or damaged in the melee.

Numerous first-person accounts by both British and French dramatize the total,

unbridled greed and savagery, and the extent to which the violence was wreaked

on material objects. Frederick Stephenson, adjutant-general of the British

army, wrote his brother:

The rooms and halls of audience... and specially the Emperor’s bedroom, were literally crammed with the most lovely knick-knacks you can

conceive.... Large magazines full of richly ornamented robes lined with costly

furs, such as ermine and sable, were ruthlessly pulled from their shelves, and

those that did not please the eye, thrown aside and trampled under foot. There

were large storerooms full of fans. Mandarins’ hats, and clothes of every description, others again piled up to the ceiling

with rolls of silk, all embroidered, and to an incredible amount.... All these

were plundered and pulled to pieces, floors were literally covered with fur

robes, jade ornaments, porcelain, sweetmeats, and beautiful wood carvings.

[4]

Garnet Wolseley, a lieutenant colonel with the British forces at the time, later

recalled arriving at the Yuanmingyuan just in time to see “a string of French soldiers going in empty-handed and another coming out laden

with loot of all sorts and kinds. Many were dressed in the richly embroidered

gowns of women, and almost all wore fine Chinese hats instead of the French

kepi.” [5] The riotous scene he recalled actually found representation in prints published

in France at the time.

Occupation of the Yuanmingyuan by Anglo-French Forces,

published in L'Illustration, December 22, 1860, France.

(full image and detail highlighted in red)

[ymy7121] Wikimedia Commons