|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

The earliest known photographs of the ruins of the European section of the

Yuanmingyuan were taken by Ernst Ohlmer in 1873, just 13 years after the

looting and destruction of the site. 12 of the original glass negatives

were collected for an exhibition at Beijing's China Millennium Monument in 2011.

This depicts the north side of the Xieqiqu, one of the main

palaces.

[ohlmer_1873]

In October 1860, the Second Opium War came to a violent end when British and

French forces sacked and destroyed the sumptuous imperial retreat known as the

Yuanmingyuan. This was defended at the time as a proper response to the torture

and murder by Qing officials of a delegation of foreigners sent to Beijing in

the final stages of the conflict. In the imperialistic rhetoric of the time,

wantonly destroying one of the greatest treasures and pleasures of the imperial

court was justified as a fitting and civilized act by which to punish China and

its leaders for their barbaric behavior.

The sack of the Garden of Perfect Brightness was thoroughgoing and left no

buildings intact. Although scavenging and looting of the site continued for

decades thereafter, for all practical purposes the Chinese section was

obliterated while the stone and marble palaces and pavilions of the European

section survived only as ruins and rubble. Yet the Yuanmingyuan also lived on

in two very different, but equally compelling, ways.

Despite the rampant trashing of untold treasures that had been housed in this

vast complex, many valuable objects of art were taken as plunder and made their

way into the great “Oriental” collections of the West, particularly in England and France. The issue of

looted Chinese art and artifacts, many dating back to this time, continues to

make news today.

On the other side of the coin, in Chinese popular consciousness the destruction

of the Yuanmingyuan has lived on as perhaps the single most powerful symbol of modern China’s humiliation at the hands of the rapacious foreigners. The ruins of the Western buildings

have been turned into a popular theme park—simultaneously a stark reminder of Western barbarity and celebration of Chinese

nationalism. Once the nation’s Communist leaders reversed course and embraced rather than denounced the

accomplishments of earlier generations—even the Manchu emperors—the Garden of Perfect Brightness became a natural media window for

remembering and embracing the great traditions and accomplishments of China’s past.

OPIUM WARS: THE FINAL ACT

In October 1860, British and French troops plundered and destroyed virtually the

entire Yuanmingyuan complex of elegant Chinese and European-style buildings.

This notorious act marked the final chapter in the so-called Second Opium War

(1856-60), and became a vivid symbol of rapacious Western imperialism to which

Chinese historians have never ceased to call attention. Dissatisfied with the

terms of the Treaty of Nanjing that ended the First Opium War (1839-42), the

British and French used various pretexts to secure further trade rights, gain missionary privileges, and, in particular, establish diplomatic representation at Beijing. They

wished to conduct diplomatic relations with China as equal sovereign states

rather than following outdated tributary-state rituals traditionally demanded

by the Chinese court. By so doing, they could further their own imperial

ambitions in China.

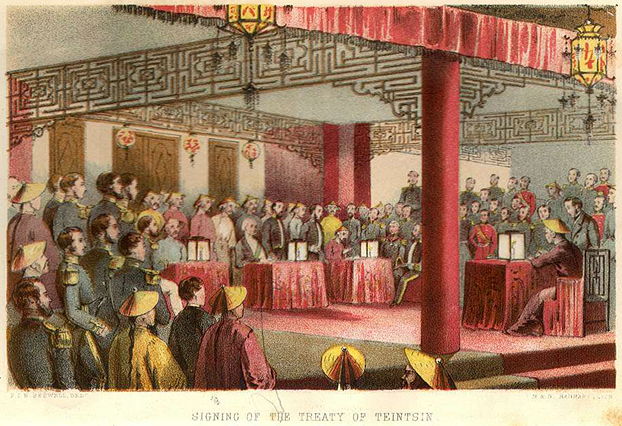

In 1858, after a series of naval skirmishes, British forces under Lord Elgin

(James Bruce, son of Thomas Bruce of “Elgin Marbles” fame) proceeded to northern China. Backed by French troops, they captured the Dagu

(Taku) forts, and arrived at the port of Tianjin (Tientsin), about 80 miles

from Beijing. Under the threat of direct force, the emperor Xianfeng (r.

1851 to 1862)—only 27 years old—authorized two high-ranking officials to negotiate the Treaty of Tianjin, which

gave the foreign powers practically everything they sought.

The next year, the newly-appointed British envoy Frederick Bruce, who was the brother of Lord Elgin, returned to China expecting to exchange treaty ratifications in

Beijing. The court, seeking every way to avoid this, ordered an attack on

British forces at Dagu forts when they tried to proceed to Beijing by river

rather than the prescribed land route. Taken by surprise, the British lost

four gunboats and 89 men, and sustained hundreds of casualties. They were forced to

retreat.

The French supported the British and the two nations returned the following

summer with a much larger joint military force. On August 21, 1860, they

successfully attacked the Dagu forts and, four days later, took the city of Tianjin. At this

point the court agreed to have treaty ratifications take place in Beijing, but

further complications developed when the court ordered the arrest of Harry

Parkes, a controversial British diplomat who was serving as the interpreter to

Lord Elgin. The British forces continued to advance on Beijing, reaching the

northern Anding Gate of the Forbidden City on October 5.

Lord Elgin at the 1858 “Signing of the Treaty of Tientsin,” frontispiece, Narrative of the Earl of Elgin's Mission to China and Japan in the years 1857, ‘58, ‘59, volume 1, by Laurence Oliphant, published 1859.

[1858_TreatyTeintsin_bx]

For more British views of the 1859 campaign from this volume,