| |

|

|

| |

”A picture of an ambush at Tianjin city using land mines, and the great victory of Commander-in-chief Dong over the Western forces. The first month of autumn in the Gengzi year of the Guangxu reign [1900].” ”A picture of an ambush at Tianjin city using land mines, and the great victory of Commander-in-chief Dong over the Western forces. The first month of autumn in the Gengzi year of the Guangxu reign [1900].”

Chinese nianhua woodblock print, 1900

[lbx_na06_NatArchives010]

When war broke out with China in 1900, eight foreign armies prepared to invade the capital of Beijing, while Boxer militia forces and Qing troops besieged foreign diplomats and missionaries in their legations. This unit describes the war between the foreigners and the Qing and Boxer forces, the siege of the legations in Beijing, and the occupation, looting, and massacre that followed.

These dramatic events attracted the attention of media around the world, including pamphlets and pictures appealing to the Chinese rural population. The New Year’s print above celebrates an early victory by Qing forces and Boxer militia over foreign armies outside Tianjin. Images of the Boxer Uprising delivered to the Chinese public differed radically from the versions portrayed in the Western news media, but both sides exaggerated their victories and minimized their defeats. We include twelve of the Chinese prints, with translations and commentary, to show the rarely seen Chinese perspective on the war of the Qing court and Boxers against the foreign powers.

|

|

|

| |

WAR & SIEGE

Foreign Diplomats in Beijing Before the Siege: 1898

Before the Boxer war began, foreigners had lived in an uneasy state of coexistence with the Qing court in Beijing for nearly fifty years. The treaty provisions of the Second Opium War had granted them the right to reside in the capital, but the Qing rulers only reluctantly accepted their presence.

The eleven foreign legations in Beijing were located in a single quarter in the southern district of the city, just inside the wall of the Tartar City, or outer wall of the capital. This was the district where—before the 19th century—Mongols, Tibetans, Koreans, Vietnamese, and other tributary vassals had stayed when they presented gifts to the emperor. Each of the new Western powers rented and renovated old palaces, with gardens in the center, courts, pavilions, housing, and other buildings arranged around them. By 1900, many other foreign institutions, including the Hong Kong and Shanghai bank, Imperial Maritime Customs, the Peking hotel, and other foreign stores had joined them. The legation street which ran through the center of the quarter was unpaved, filled with sewage, and crowded with animals, people, and carts.

The diplomats and their families spent nearly all their time in the comfortable seclusion of their legations, only sending servants out to get supplies. They could play tennis, hold teas and parties, and attend balls and official dinners among themselves all year round. During the hot summers, they sent their families outside the city to the cool Western Hills, hosted by priests at local Buddhist temples. They very seldom came into contact with Chinese officials. The Zongli Yamen, China’s new Foreign Ministry, was located far away in the eastern part of the city, and its suspicious officials held only formal ritualistic meetings with the foreign diplomats.

The Empress Dowager Cixi, grandmother of the emperor, kept herself and the emperor secluded from both foreigners and the Chinese population nearly all the time. Once a year the emperor went in a grand procession to bow down at the Temple of Heaven and Temple of Agriculture, but no foreigners could view the ceremonies inside. Yet, the empress dowager was curious about the customs of foreign women, and she commissioned photographers to record her meetings with several visiting women.

When she received the wives of foreign diplomats on December 19, 1898, the audience was recorded in foreign newspapers. It was almost the last time that Chinese and foreigners in the city could meet together in peaceful circumstances.

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

“The Audience given by the Empress-Dowager and the Emperor of China to the Wives of the Foreign Ministers at Peking, on December 19”

The Illustrated London News, March 18, 1899

Artist: Henry Charles Seppings Wright

[iln_1899_v1_007]

|

|

| |

“Au Palais Impérial de Pékin.

L'Impératrice De Chine Recevant Les Dames Européennes”

Le Petit Parisien, Supplément Littéraire Illustré

December 18, 1898 (No. 515)

[lpp_1898_12_18_cixi]

|

|

| |

1899: The Court & the Foreigners Come into Conflict

As the Boxers began their rampage through the countryside, the court in Beijing, dominated by anti-foreign reactionaries, had resolved in 1899 to try to protect Christians, but not to suppress the Boxers with military force. On January 3, 1900, it ordered Yuan Shikai (1859-1916), the new Governor of Shandong, not to use force against the Boxers.

In a decree to the foreign powers, it declared:

When peaceful and law-abiding people practice their skill in mechanical arts for the self-preservation of themselves and their families, or when they combine in village communities for the mutual protection of the rural population, this is only a matter of mutual help and mutual defense.[1]

The British, American, French, German, and Italian ministers protested the decree and demanded the immediate suppression of the Boxers. The court considered officially authorizing the Boxers as militia troops, but Yuan Shikai strongly objected that the Boxers had never been a village militia, but were only a heretical sect.

The foreign powers themselves decided to strengthen guards at their legations. The first conflict between Boxers and foreign troops occurred on May 31 near Tianjin when 25 Russian Cossacks rescued a group of European engineers, killing many Boxers.

The 1st Intervention: the Seymour Expedition, Defeated (June 10–28, 1900)

By June 6th the Boxers had cut railway communications between Beijing and Tianjin. The British minister called on Admiral Sir Edward Seymour in Tianjin to send reinforcements to Beijing. His force of 2000 English, French, German, Russian, Japanese, and American troops set out from Tianjin on June 10 on board five trains for Beijing. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

Troops on board trains can be glimpsed in these photographs captioned “Departure from Tientsin of Admiral Seymour's Column for Beijing”

June, 1900

Source:

Visual Cultures in East Asia

(View top image) (View bottom image)

[vcea_1900_NA02-02] [vcea_1900_NA02-01]

|

|

| |

Chinese troops sabotaged the tracks and fought pitched battles with Seymour’s troops. By June 13, the “First Relief Expedition” that had confidently set out for Beijing was forced to turn back, abandoning the trains to find overland routes back to Tianjin. Chinese forces—including Boxer militia, imperial Qing troops, and the Gansu Braves recruited by General Dong Fuxiang—attacked the retreating columns, inflicting heavy casualties. Seymour lost 300 men, and found himself surrounded by large masses of Chinese peasant militiamen. The foreign media at this point first took notice of the large scale of upheaval in China.

|

|

|

| |

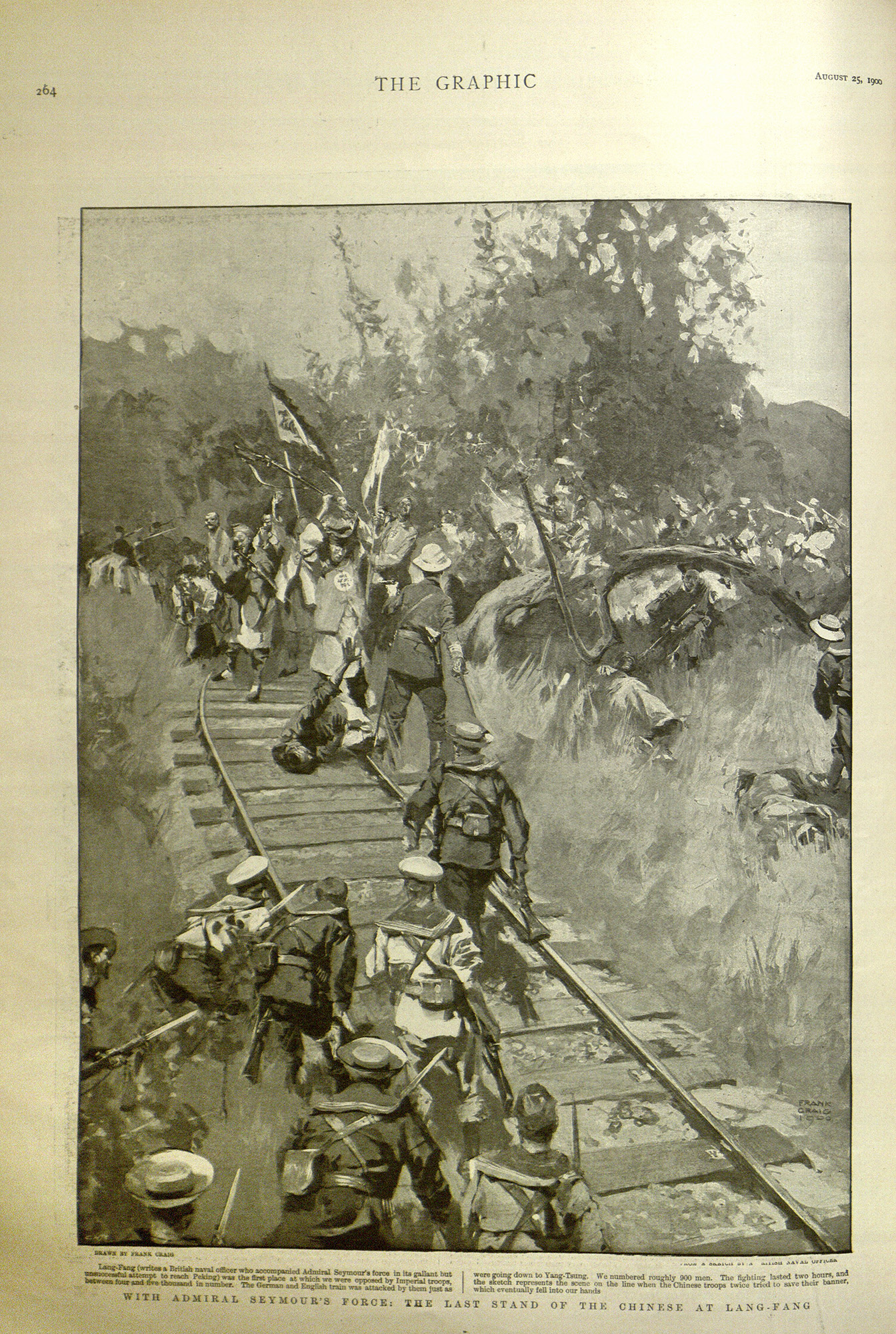

“With Admiral Seymour’s Force:

The Last Stand of the Chinese at Lang-Fang.

Lang-Fang (writes a British naval officer who accompanied Admiral Seymour’s force in its gallant but unsuccessful attempt to reach Peking) was the first place at which we were opposed by Imperial troops, between four and five thousand in number. The German and English train was attacked by them just as were going down to Yang-Tsung. We numbered roughly 900 men. The fighting lasted two hours, and the sketch represents the scene on the line when the Chinese troops twice tried to save their banner, which eventually fell into our hands.”

The Graphic,

August 25, 1900

[lgraphic_1900_031i]

|

|

| |

The Boxers blocked the Seymour expedition on June 13, and a large detachment of them entered Beijing, burning churches and foreign houses in the city. The American Monthly Review of Reviews recounted the Seymour expedition’s failure to reach Beijing with these words:

At that time Admiral Seymour’s force of English, Russian, German, American, French, and Japanese troops sent out to the relief of the legations was evidently in trouble somewhere between Tientsin and Peking. On June 26, the expedition returned to Tientsin. It had failed to come within 25 miles of Peking, had lost nearly 300 men in battle with comparatively enormous masses of Chinese insurgents and soldiers, and thought itself lucky to escape annihilation. Seymour’s failure brought to the world the first realization of the overwhelming nature of the trouble.[2]

This account makes clear that Seymour's expedition was a failure, and implies that the disorganized foreign force greatly underestimated the strength of the Chinese forces they faced. Seymour's troops fought not only against Chinese peasant martial artists and militiamen, but detachments of the Qing army and highly skilled Gansu Braves led by General Dong Fuxiang. Captions and illustrations in the foreign press, however, give the implication that Seymour nearly won the battle, and turned back voluntarily.

|

|

|

| |

“Admiral Seymour’s Relief Column:

the Wounded on the March to Tientsin.

‘After fighting our way through with rebels, who tore up the rails faster than we could lay them again,’ writes a correspondent, ‘we were confronted with Chinese imperial troops to the number of 16,000 or 20,000. A battle ensued, which lasted from noon till 6 p.m. on June 18, and our casualties being very heavy, we were forced to retire to within twenty miles of Tientsin again, where we found it impossible to retire farther by train on account of the bridge over the river being destroyed. The wounded were placed in junks at this point, the train was deserted, each man took provisions for two days, and the march started by river back to Tientsin. We had several ‘Boxer’ prisoners, who were made to tow the junks, and bluejackets used poles on board them.’”

The Graphic, September 8, 1900

Drawn by W. Hatherell, R.I.

From a sketch by Robert Carr

[lgraphic_1900_031i]

|

|

| |

Chinese New Year’s prints, however, like the graphic that begins this unit shown in a close up detail below, celebrated the victory with colorful scenes of banners, smoke, and troops waving swords, driving back the helpless foreign armies. (For more discussion of the New Year's Prints, see Chapter 2: “The View from China.”)

|

|

| |

”A Picture of an Ambush at Tianjin City using Land Mines, and the Great Victory of Commander-in-Chief Dong over the Western Forces. The First Month of Autumn in the Gengzi Year of the Guangxu Reign [1900],” (detail).

Chinese nianhua woodblock print, 1900.

This close-up detail of a nianhua print shows Chinese forces fighting foreigners in Tianjin. The explosion on the right, depicted as a Buddhist image of hellfire, throws bodies into the air. A Japanese woman appears within the enclave on the bottom right. Beheaded foreign soldiers and a volley of cannon balls, banners, and ships appear in the battle.

[lgraphic_1900_031i]

|

|

| |

Many types of maps appeared in Western publications that illustrated the embattled area in China, including illustrative, bird’s-eye views like the following, “From the Pei-Ho to Pekin: A Bird’s-eye View of the Disturbed Area in China.” The full-page spread in Leslie’s Weekly depicts and describes the trajectory of the Seymour expedition.

|

|

|

| |

“From the Pei-Ho to Pekin:

A Bird’s-eye View of the Disturbed Area in China.

On this bird’s-eye map all the important points between Taku and Pekin are to be seen in their relative positions. The absolute distances are given in the adjoining table. The route of the unsuccessful relief force lay along the railway from Tientsin to the village of Lang-fang, a party of bluejackets from H.M.S. ‘Aurora’ pushing as far as Anting. On June 16 the force was compelled to return to Yang-tsun, from which it fought its way back to Tientsin, taking the wounded in boats down the Pei-ho. Only low hills break the surface as far away as the Great Wall, which is seen rising like a rampart in the distance.

Distances

Taku to Tientsin - 27 miles

Tientsin to Pekin - 79 miles

Tientsin to Yang-tsun bridge - 17 miles

Tangku to Chung Liang Cheng - 13 1/2 miles

Pei-ho River to bar at mouth - 6 miles”

Leslie’s Weekly, 1900 (vol. 90, p. 24)

[leslies_1900_v90_2_024]

|

|

| |

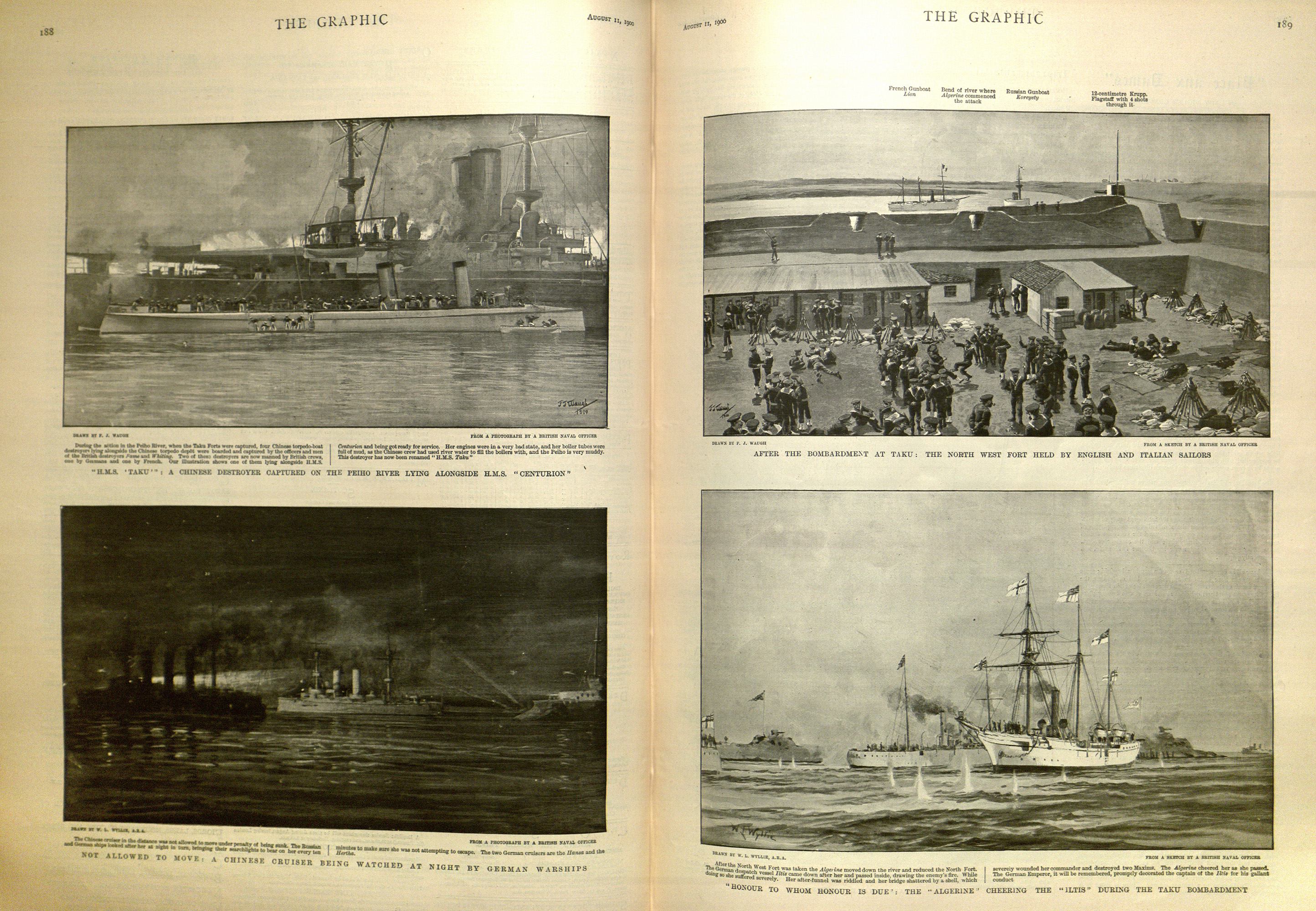

Foreign Powers Attack the Forts at Dagu (June 16–17, 1900)

While Seymour was still on the way to Beijing, the Allied navies decided to attack the Dagu forts guarding the mouth of the Hai River that led from Tianjin to Beijing. On June 17, after weak Chinese resistance, the Allies assaulted the forts and captured them quickly. Even though the Chinese had modern destroyers, they were unable to use them. The news of the loss pushed the Qing government to support the Boxers unequivocally and to ally with them to expel foreign armies from Chinese soil.

This Chinese New Year's print shows the Chinese defenders firing cannon in a duel with the foreign warships. The New Year's prints, like the foreign media, quickly broadcast simple accounts of the battle to a broad engaged public.

|

|

|

| |

Foreign powers launch a naval attack on the forts at Taku (Dagu)

Chinese nianhua woodblock print, 1900

各國水軍大會天津唐沽口

Translation: “All countries’ navies gather at Tianjin’s Tanggu Kou.“

率眾軍還炮應擊,互有損傷,未分勝負云

Translation: “[Our armies] responded with cannon attacks. Each side has amassed casualties, but the winner has not yet been determined.”

Image, left: 大沽口西炮台;大沽口;俄羅斯水軍极快兵船

Translation: “The Western cannon battery at Dagu Kou; Dagu Kou; The Russian Navy’s extremely fast vessel”

Image, right: 紫竹林;英國兵船 俄罗斯军极快兵船; 法国兵船

Translation: “Purple bamboo forest [Place name];

English warship; Russian fast warship; French warship”

[na12_NatArchives004]

|

|

| |

“H.M.S. ‘Taku’: A Chinese Destroyer Captured on the Peiho River Lying Alongside H.M.S. ‘Centurion.’” Detail (above) from 2-page spread (right)

The Graphic, August 11, 1900

[graphic_1900_026_11Aug]

|

|

| |

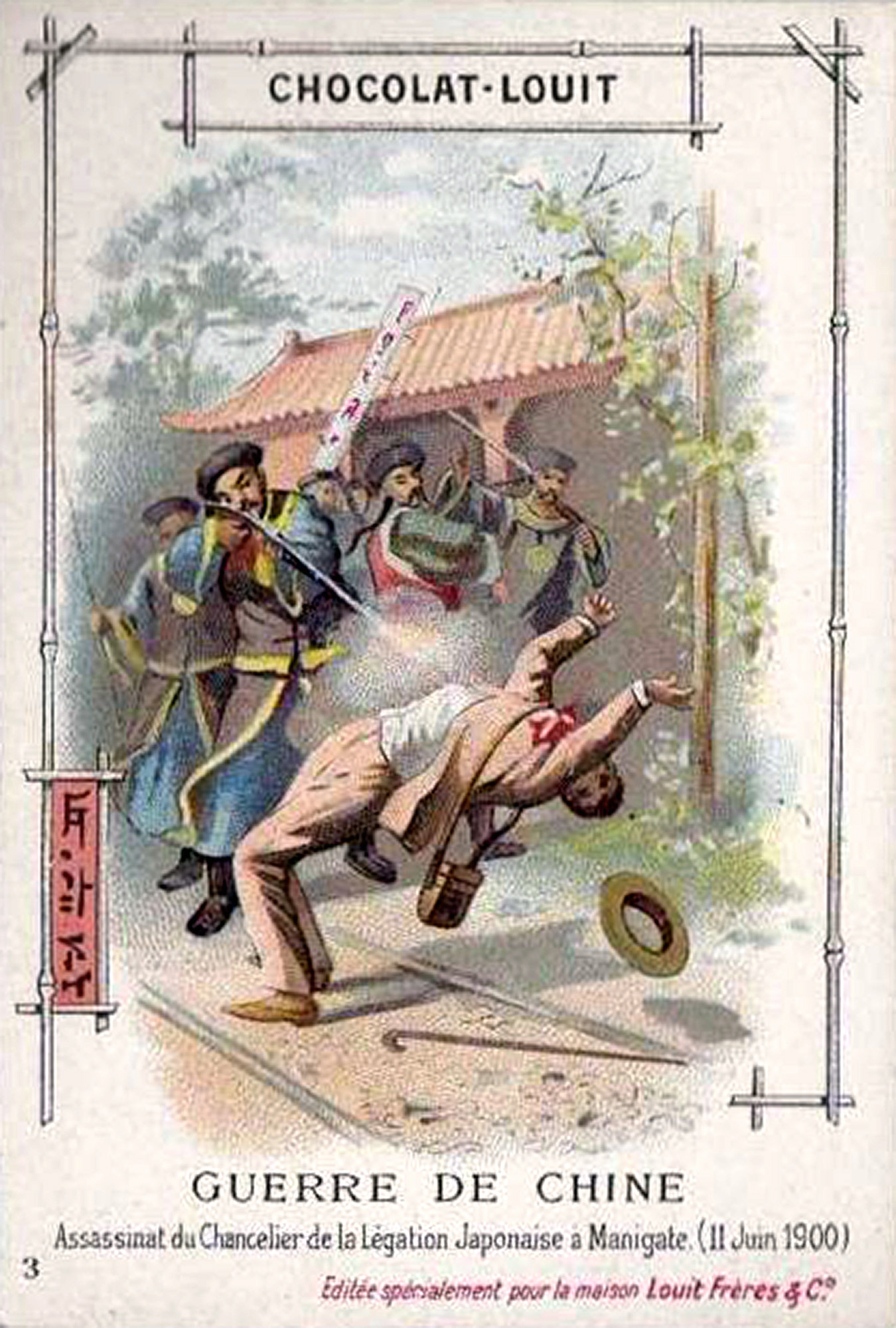

Murder of Foreign Diplomats (June 11 & June 20, 1900)

By June 1900, the Boxers, supported by Qing troops, had killed the chancellor of the Japanese mission and the German ambassador, burned the British summer legation west of Beijing, and cut off telegraph contact of the city. The legation quarter in the southeast district of the city came under siege. Foreign troops shot Chinese civilians who were suspected of being Boxers, and the German minister, Baron von Ketteler, was killed in the street on June 20 by Muslim Gansu Braves after he killed a Chinese boy.

For a while, the court made conciliatory moves, offering to feed the foreigners in the legations and escort them safely out of Beijing, but it was too late. Now the court openly supported the Boxers, and the siege of the legations began.

The assassinations of foreign diplomats stimulated further agitation in Western media against Chinese savagery. The images spread not only through news media, but commercial products, even including chocolate cards. French chocolate cards contain an incongruous mixture of pictures of martyrs, close-up battles, and gruesome executions embedded in advertisements. But these pictures give accurate dates and locations of battles, published in a series, so that the French consumer could keep up with the news from far away while enjoying his chocolate safely at home.

|

|

| |

Shooting of M. Sougiyama

“Assassinat du Chancelier de la Légation Japonaise a Manigate (11 Juin 1900)” Chocolat-Louit card

[choc-louit03_1900_11June_3] |

|

| |

“Événements de Chine.

Assassinat du Baron de Ketteler, Ministre d’Allemagne”

Le Petit Journal, Supplément Illustré, July 22, 1900

Source: Widener Library, Harvard University

[lpj_1900_07_22_widener]

|

|

| |

Declaration of War Against Foreign Powers (June 21, 1900)

By June 16, the Empress Dowager and her Imperial Council had resolved to resist the entry of foreign troops into the capital. She stated, “The Powers have started the aggression, and the extinction of our nation is imminent... If we must perish, why not fight to the death?”[3]

After the Allied naval forces attacked the Dagu forts that protected the port of Tianjin, the court declared war on June 21.

The court formally supported the Boxers only after the declaration of war, now praising them for their patriotism and wishing them success. Qing officers now collaborated with Boxer militia to enroll more fighters against the foreign menace. Wall posters in cities like Tianjin spread the news of the anti-foreign conflict.

|

|

|

| |

“‘Kill the Foreigners’: Natives Reading an Anti-Foreign Manifesto in Peking.

Not only in Peking, but in the villages between the capital and Tientsin, the “Boxers” have posted up placards calling upon the readers to kill all foreigners. They have been exciting ignorant superstition against Europeans in this way for some time now.”

The Graphic, June 23, 1900

Artist: Frank Dadd

[graphic_1900_004b]

|

|

| |

“Tientsin – Dernieres Nouvelles – Latest News”

Translation of Chinese text above wall: “World News for Your Benefit.”

French postcard, Tianjin.

[1900s_TientsinCrd_stmpbds]

|

|

| |

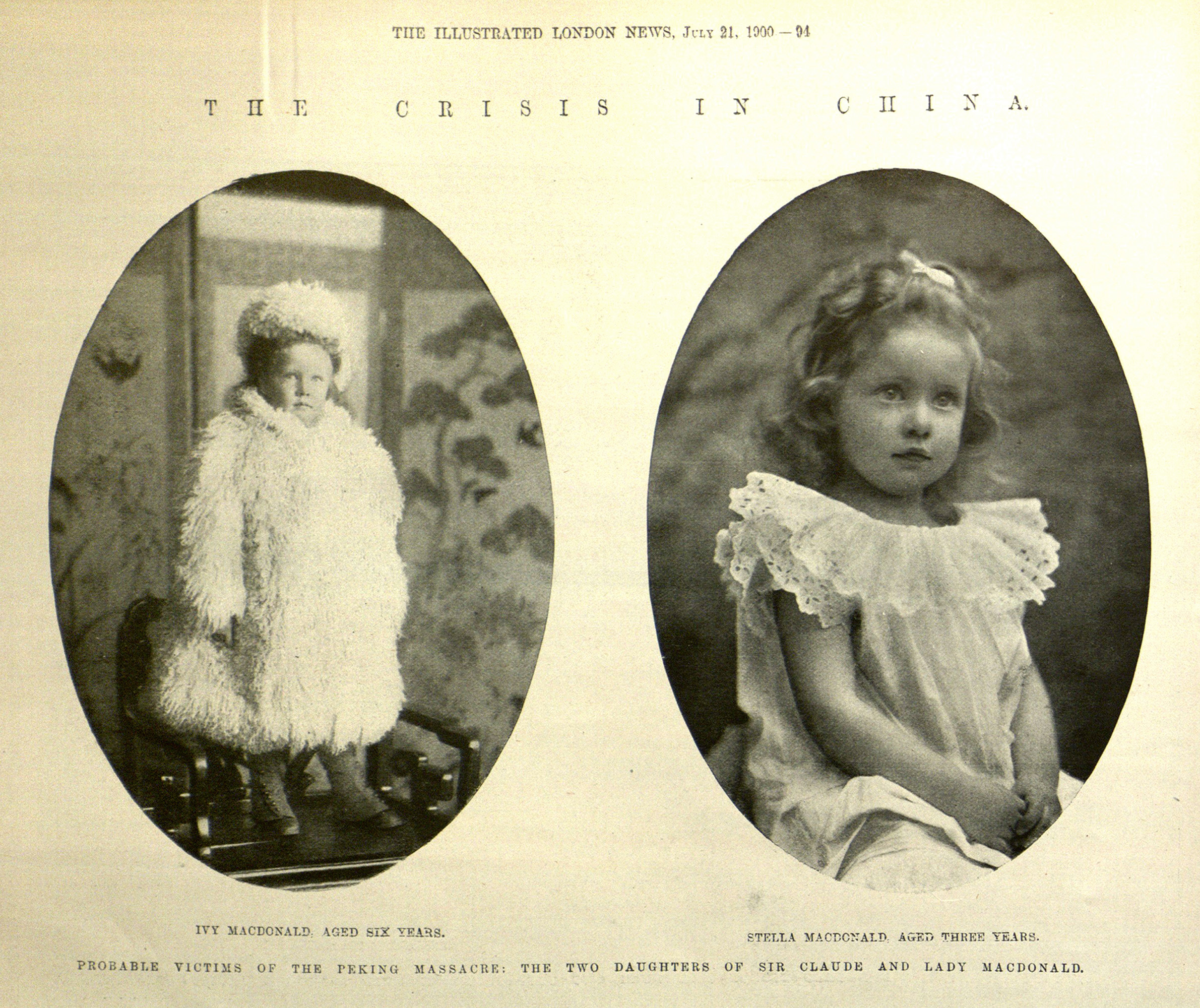

As the Boxers rampaged through Beijing, putting up wall posters calling on Chinese to kill foreigners, foreigners retreated to the legation quarter. The court heard of foreign victories in Tianjin and the death of the distinguished general Nie Shicheng, leader of a Western-trained army who had fought in the Sino-Japanese War. The southern provincial leaders, on the other hand, had no interest in fighting the foreign powers, and they pressed the court to negotiate. This period of the war attracted the greatest foreign media attention, but information was scarce and unreliable. The foreign press raised fears with sensationalist, inaccurate reports of massacres, stressing the pitiable condition of foreign women trapped in the legations. Few reports mentioned that large numbers of Chinese Christians had also taken shelter within the legation walls. Photographs from within the legation stress the preparations made for defense and the cooperation among missionaries, diplomats, and soldiers to maintain the community's morale.

|

|

|

| |

“The Crisis in China.

Boxers Enrolling at a Military Post.

Along the roads of China are encountered great numbers of military posts at which small garrisons, about ten or fifteen soldiers in time of peace, are stationed. Close by is a look-out commanding an extensive prospect. The cones of brickwork and plaster are used to fire out a fierce combustible in time of alarm as a signal to the next post. They are also employed on all festive occasions. It is here that the Boxers now enrol [sic] themselves and are sworn in to form their semi-military corps. A Government official belonging to the army presides at the table. He is, as the umbrella indicates,

a Mandarin of consideration.”

The Illustrated London News

July 14, 1900 (no. 55)

[iln_1900_v2_015]

|

|

| |

The 55-Day Siege in Beijing (June 20 – August 14/15, 1900)

The siege began on June 20, and lasted until foreign Armies entered Beijing on August 14 and 15. During these 55 days, two sites in Beijing were under siege: The Northern Cathedral and the Foreign Legation Quarter. 900 foreigners and 2,800 Chinese Christians held out in the legation quarter, and 71 priests, nuns, and soldiers, along with 3,400 Chinese Christians in the Northern Cathedral.

|

|

| |

“The British Legation at Peking,

where the foreign ministers were besieged from June 20 to August 15.”

American Review of Reviews (vol. i, p. 285), 1900

[AmRofR_1900_v1_015_detail]

|

|

| |

“The Legations at Peking, 1900”

From a sketch by Capt. John T. Myers

[Western_Legations_Peking_19]

|

|

| |

The press raised fears with sensationalized inaccurate reports. For example, the “Probable Victims of the Massacre at Peking” in the July 21, 1900 Illustrated London News featured portraits of diplomats, missionaries, and children who were the supposed victims of a massacre that never took place.

|

|

|

“Probable Victims of the Massacre at Peking,”

“Probable Victims of the Massacre at Peking,”

The Illustrated London News, July 21, 1900

(above, and detail left)

[iln_1900_v2_021]

[iln_1900_v2_027b] | |

| |

Photographs taken inside the legations reveal siege life, including the internal communication centers, overcrowded makeshift sleeping quarters, food preparation that in time meant butchering the ponies for food, defense of the legations from fire and gunfire, executed and dead bodies on the streets, and the graves honoring those killed in the attacks. The photographs offer a rare view of the many Chinese Christians who escaped Boxer attacks by taking refuge in the legations. Despite receiving inadequate shares of provisions, these Chinese refugees contributed heavily to the survival of the residents.

|

|

| |

Reverend Charles A. Killie photographs from

the series “The Siege in Peking”

Left: No. 51. Killie’s captions explain that Chinese Christians help combat a “fire started in the Mongol Market by the Boxers.”

Right: No. 38, the lone sentry at the wall, an American Marine “on guard when the photograph was taken, was afterwards killed.”

[killie51_46860_yale_36]

[killie38_46853_yale_29]

|

|

|

| |

Isolation and poor communication heightened the fears of the foreigners both overseas and inside the siege.

Left: “No. 62. In the British Legation. The only messengers (out of a score or more sent) who succeeded in getting to Tientsin and return. Although they went in all sorts of disguises, all but those three were understood to have been either killed or captured.”

Right: “No. 36. In the Methodist Compound. Group just within the big gate, listening to alarming rumors.”

Photographs from the series “The Siege in Peking”

by Reverend Charles A. Killie

Source: Yale University

[killie62_46869_yale_45]

[killie36_46869_yale_28]

|

|

|

| |

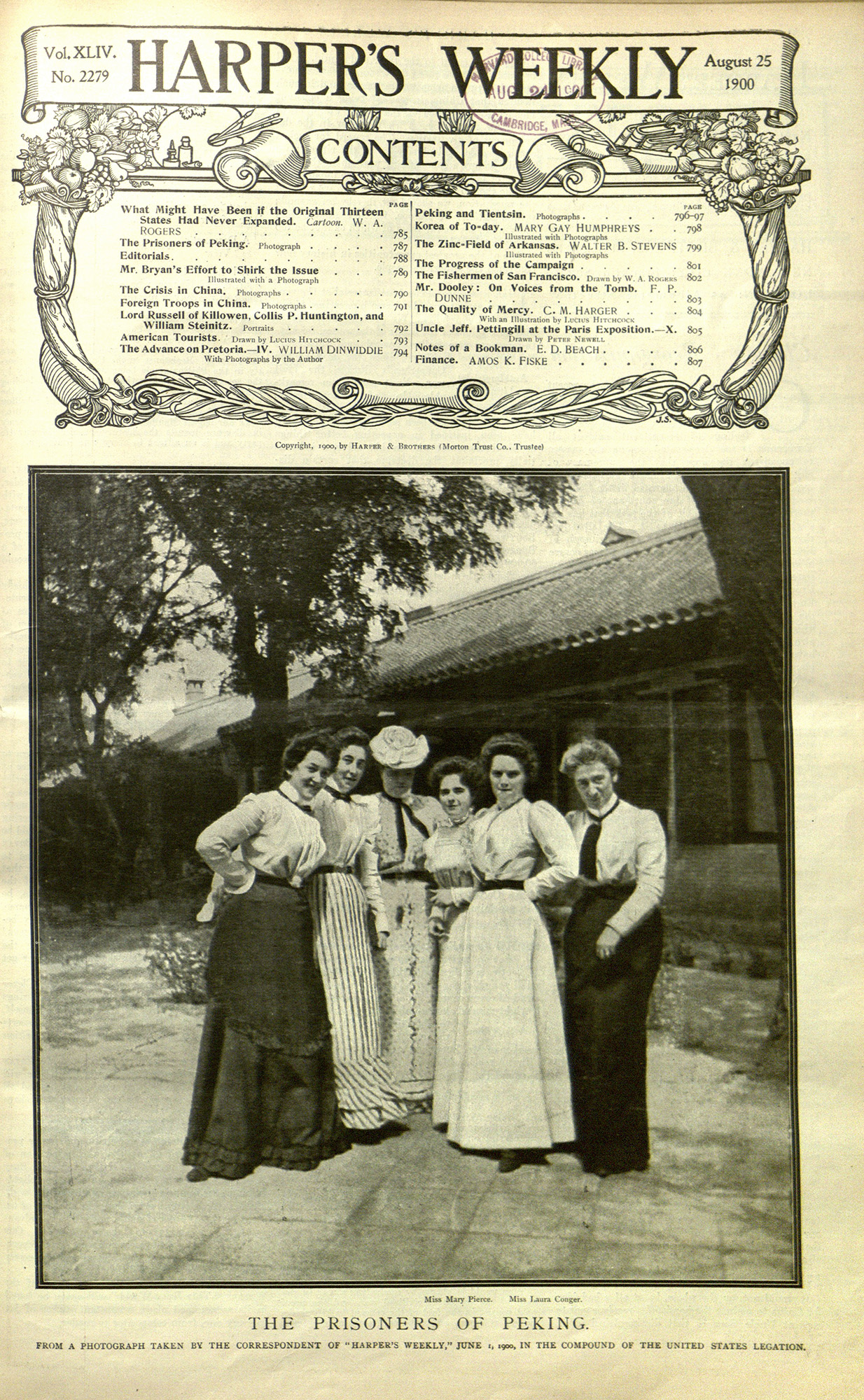

Images of women in captivity had always been surefire means to arouse public sympathy. The repeated images of women carried in cages portrayed during the Opium War now echoed in portraits of dignified women confined behind the walls of the legations.

“The Prisoners of Peking. Miss Mary Pierce. Miss Laura Conger.

From a photograph taken by the correspondent of ‘Harper’s Weekly,’ June 1, 1900, in the Compound of the United States Legation.”

Harper’s Weekly,

August 25, 1900

[harpers1900_07b_v2b_019]

|

|

| |

Battle of Tianjin (July 13–14, 1900)

Tianjin, a large city of one million Chinese on the coast southeast of Beijing, contained a substantial foreign settlement of about 700 people along the banks of the Hai River. On June 15 and 16, Boxers from the countryside destroyed Christian churches in the city, killed Chinese Christians, and attempted to attack the foreign settlement. At this point, the Qing government decided to support the Boxers, besieging and bombarding the foreigners. After the failure of Admiral Seymour’s efforts, the Allies prepared a large force to assault the city and raise the siege. Japanese soldiers broke through the south gate while Russians broke through the east gate, and the Chinese soldiers withdrew. The Allied forces, however, had no unified command, so they quickly turned to looting, rape, and acts of vengeance against Chinese civilians. The very able general Nie Shicheng was killed, leaving only Dong Fuxiang and his Muslim Braves to resist the march of the foreign armies on Beijing. The impressive resistance of Chinese troops at Tianjin, however, forced the allied armies to delay their final advance until August. The images shown here portray Chinese Christian refugees, Allied troops, and dramatic—though imaginary—battle pictures by Japanese and Chinese artists.

|

|

|

|

| |

陸軍與團民鏖戰圖

Translation: “A Battle Picture of the Bitter Fight Between the [Western] Land Army and the Boxers”

六月廿八日,團民傾巢出隊,經英法陸軍暨各國之兵與團民開仗,

我國聶軍門標下統帶從中夾攻,鏖戰多時,未分勝負云。

Translation: “On the 28th day of the 6th lunar month (July 24), the boxers turned out in full force and moved out as an army. They encountered the armies of England, France and other countries, which began to fight with them. A legion of our army under the command of General Nie attacked from the middle. They bitterly fought for a long time but neither side won the battle.”

Image, upper left: 華兵從中夾攻;義和童子軍;後隊大砲兵埋伏

Translation: “The Chinese army attacking from their midst; The Yihe [righteous and harmonious] child army; An ambush by the rear army’s large artillery troops”

Image, center: 守望相助 義和;兩軍對陣大戰

Translation: “Mutual help and protection; Yihe [righteous/harmonious]; Two armies poised for a large scale clash”

Image, right: 英法各國大兵

Translation: “England and France’s great army”

Chinese nianhua

New Year’s print, 1900

Source: National Archives

[na05_NatArchives002]

|

|

|

| |

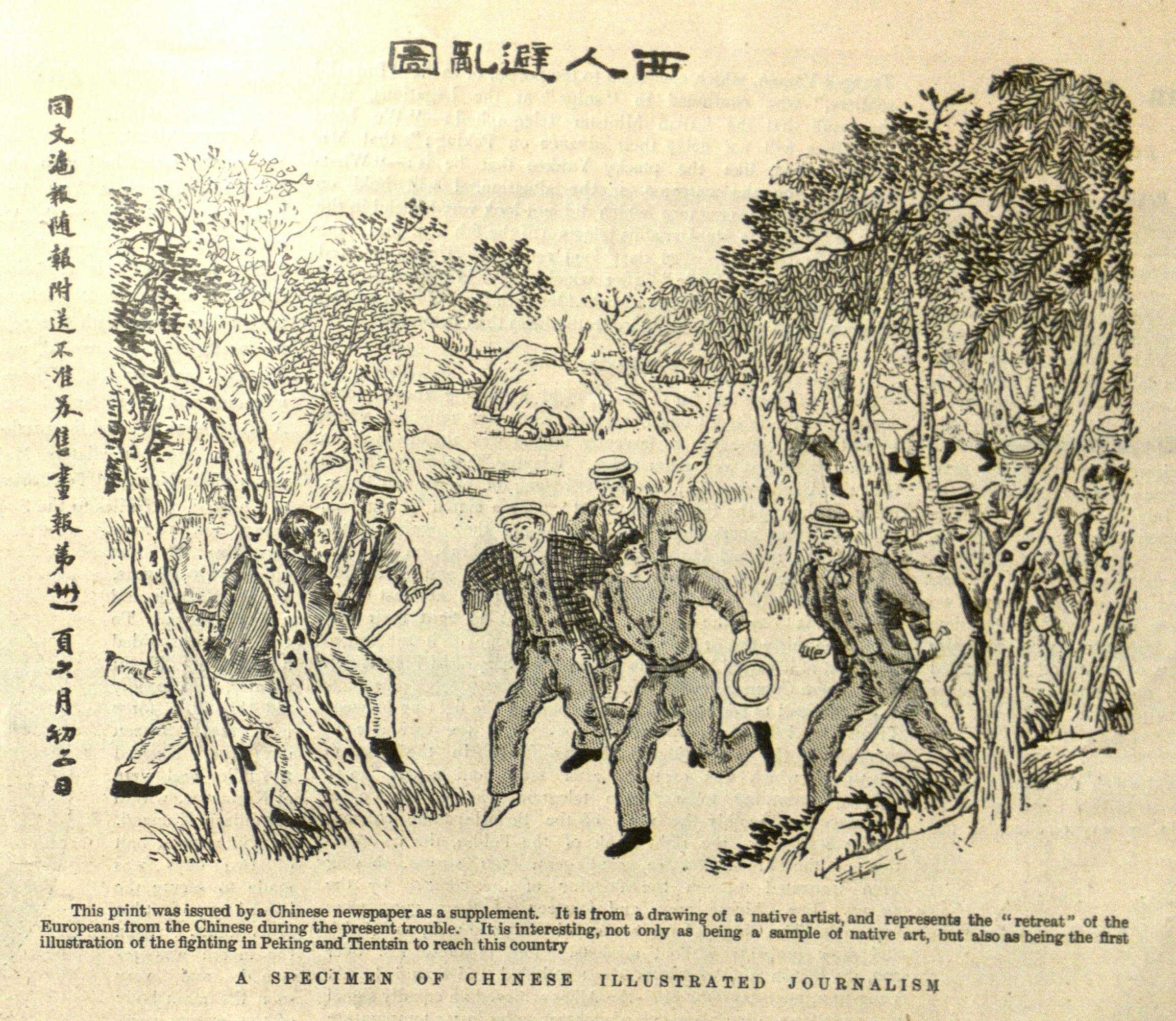

Translation: “Image of the Westerners Fleeing Disaster”

English text: “A Specimen of Chinese Illustrated Journalism.

This print was issued by a Chinese newspaper as a supplement. It is from a drawing of a native artist, and represents the ‘retreat’ of the Europeans from the Chinese during the present trouble. It is interesting, now only as being a sample of native art, but also as being the first illustration of the fighting in Peking and Tientsin to reach this country.”

Cartoon from the Chinese newspaper of Tientsin, “Tung-Wen-Hu-Pao” Reproduced in The Graphic, August 18, 1900

[graphic_1900_030]

|

|

| |

“Chinese Christian Refugees Gathered by Father Quilloux into the Apostolic Mission During Bombardment of Tientsin, China.”

Detail from stereograph

Source: Library of Congress

[libc_1901_3c03013ub]

|

|

| |

天津城廂保甲全圖

Translation: “Complete Map of the Community Self-Defense System

of the

Walled City of Tianjin and its Environs,” 1899

Artist: Feng Qihuang

Source: Library of Congress

[1899_tianjin_ct002306_map_L]

|

|

|

| |

The 2nd Intervention: March on Beijing (August 4–14, 1900)

Foreign armies gathered in Tianjin to join in an unprecedented international alliance of rivals, having chosen a commander, Alfred von Waldersee, who was still far away in Germany. The troops departed under command of British General Gaselee.

The main force of the “Eight-Power Expeditionary Army” in fact included soldiers from only five nations (Germany sent a small force that turned back after the first battle, and Austria-Hungary and Italy sent only small forces). Most of the British forces were Indian troops. The total size was about 18,000 men, consisting of 8,000 Japanese; 4,300 Russian infantry, Cossacks, and artillery; 3,000 British infantry, cavalry, and artillery; 2,500 U.S. soldiers; and an 800-man French brigade from Indochina.

|

|

|

| |

“Eight-Nation Alliance with their Naval Ensigns,” 1900

“Allied International Forces by order of troop size: Japan, Russia, United Kingdom, France, United States, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Italy.”

Japanese print

Source: Wikipedia

[dh7110_BoxerTroops_wikipedi]

|

|

| |

Images of the imperial forces who relieved the siege display openly the common assumptions and practices of the major world powers. The military forces themselves took advantage of the expedition to show their discipline, weaponry, and modern leadership. In photos of the expedition, each of the countries has an equal visual rank, with their generals lined up alongside each other. Imperial internationalism promoted a picture of united modern forces faced by mysterious but undisciplined Asian hordes. On the other hand, the powers also used the war to reinforce national loyalties, stressing that different classes of the population all held a common patriotic interest in the protection of empire and the defeat of the Chinese. The armies of the French and British included large contingents from the colonies. Sikhs and Pathans from India and the French Zouaves conscripted from the French settlers in Algeria and Tunisia stand out because of their colorful uniforms. A French image of Japanese army troops also portrays them as similar to the French, in colorful uniforms, with mustaches, sitting in stately form on horses. Japan has clearly joined the ranks of imperial military forces. Frequent pictures of large warships and guns indicated the high level of technology and destructive power of the imperial forces.

|

|

|

| |

“Troops of the Eight-Nations Alliance,” ca. 1900

Left to right: Britain, United States, Australia, India, Germany,

France, Austria-Hungary, Italy, Japan.

Source: Wikipedia

[solders_of_the_eight_nation]

|

|

| |

“No. 2 Company, Bombay Sappers and Miners, China, 1900”

Tianjin, 1900

Source: Wikipedia

From National Army Museum website: “No. 2 Company was the last of the sapper and miner units to land in China, reaching Tianjin on 11 August 1900. The company was employed for a time on the Tianjin defenses and on 19 August took part in an engagement to disperse the Boxer forces threatening the city from the south west. Towards the end of 1900 the unit was occupied in the bridging and preparing winter quarters, as well as, during the following spring, in demolishing wrecks in the Pei-Ho River.”

[1900_84115_Bombay_Sappers]

|

|

| |

The forces left Tianjin on August 4 and reached Beijing on August 14, facing very little military resistance, but suffering heavily from heat exhaustion. The foreign armies suffered very few casualties. In the next two days, they occupied and liberated the legation quarter and Northern Cathedral, and on August 28 they staged a march through the city to display their completed occupation. The empress dowager and her court had fled on August 15 to take refuge in Shanxi.

|

|

| |

Two routes followed by Allied expeditions from Tianjin to Beijing.

The Seymour expedition traveled by train, until defeat, returning over land and by boat.

The second expedition marched overland adjacent to supply boats on the Hai (Peiho) River.

(Above) “Map Showing Routes of Relief Forces.

To accompany China in Convulsion by Arthur H. Smith,” 1901

[smith438a_MapRelief_1901]

(Right) “The March to Pekin”

[RevOfRev_1900_v22_014] |

|

| |

At the same time, the Russians sent warships down the river into Manchuria, attacking and occupying the three provinces of Heilongjiang, Jilin, and Fengtian.

All the foreign journals produced dramatic pictures of the battle for Beijing, each featuring the actions of the troops of their own nation. The battle portraits contain pictures of masses of men fighting in great confusion, and views of disciplined armies charging toward the massive walls of Beijing.

They vary greatly in degrees of realism and fantasy. Many images reinforced existing stereotypes of China as a huge country, with an ancient, but degenerate civilization, taken over by barbarian hordes. Others showed specific events, demonstrating Western forces triumphing over Chinese soldiers and Boxer militiamen. An amazing array of modern mass media, ranging from newspapers, to leaflets, to advertising cards contained in consumer products like chocolate and soap, distributed the battle pictures widely.

The French magazine Le Petit Journal featured colored pictures of crowded masses of people, with very little depiction of military gore. The French had very few troops in the Eight-Power Army, so they could not display their own military contributions, but the French three-color flag flies prominently among the large military forces.

|

|

|

| |

“Événements de Chine.

Une Victoire Française”

Le Petit Journal, Supplément Illustré, January 13, 1901

[lpji_1901_01_13th_2]

|

|

| |

The most dramatic of all the siege pictures is a French illustration showing close combat between foreigners firing machine guns and Chinese storming the wall. (Note that in this picture the Chinese troops use artillery as well, and the image features militarily trained forces instead of Boxer peasants.)

|

|

| |

Not to be outdone, a dramatic Japanese print celebrates the charge of Japanese troops on the walls of Beijing. Atmospheric views of Beijing seen through clouds of smoke echo the fanciful illustrations of the Sino-Japanese War by artists who had never seen the front.

|

|

| |

English caption on Japanese print: “The fall of the Pekin Castle, the Hostile Army Being Beaten Away From the Imperial Castle by the Allied Armies.”

September, 1900

Artist: Kasai Torajirō

Source: Library of Congress

[j_1900_BeijingCastleBoxerR]

|

|

| |

Another print depicts Japanese Red Cross representatives tending to wounded Western soldiers while Japanese officers mingle with the Allied commanders. Japan asserts its equality with the imperial armies while clouds of smoke billow over the walls of Beijing in the distance.

|

|

|

| |

Japanese imagery did not stress religious themes, and it represented both the coercive and the restorative functions of the expedition. In Western imagery, however, drawings of attacks on missionaries aroused the most popular sentiments. Descriptions of Boxer attacks drew explicitly on stories of martyrdom in the Christian tradition dating back to the Elizabethan writer John Foxe’s Book of Martyrs. Even though details of the events were scanty, it was all too easy to fit the Boxer attacks into a narrative that followed closely the 16th-century hagiographic text, in which all Christians, foreigners and Chinese alike, were innocent, heroic victims of savage brutality.

Depictions of Boxers massacring Western missionaries appeared alongside Western retaliation with looting and destruction of government buildings, giving viewers a sense of righteous revenge. But in this narrative, order soon returned, with the troops marching into the Forbidden City and the besieged missionaries gratefully receiving their liberators.

|

|

|

| |

Massacre of the Russian missionaries.

“Événements de Chine.

Massacre dans l'Église de Moukden en Mandchourie” [sic]

Translation: “Massacre in the Mukden Church in Manchuria”

Le Petit Journal, Supplément Illustré, August 5, 1900

[lpji_1900_08_05th_9]

|

|

| |

“Événements de Chine.

Les Marins Allemands Brulent le Tsung-li-Yamen.”

Translation: “German Sailors Burn Tsung-li-Yamen”

Le Petit Journal, Supplément Illustré, July 22, 1900

[lpji_1900_07_22nd_9]

|

|

| |

Water gate through which British forces walked, the first to reach the legations.

Source: Library of Congress

[libc_1900_3a49563u]

|

|

|

| |

“The Site of the British Legation at Peking; Driving the Troops of Fung Fu Hsiang [Dong Fuxiang] From the Hanlin Yuan.

The Imperial troops were driven from the Hall of the Hanlin Yuan, or National Academy, by a sortie made by a small party of defenders of the British legation—British and American. The Hanlin Yuan had the night before been reconnoitred by the British. The officer in command of the reconnoitring party was probably the first European to enter this home of Chinese learning, which is a century old, and contains a priceless library, and is as sacred to Chinese as probably Mecca is to Musulmans. All this tradition had no weight with the Imperial troops, who even fired the library in order to enter the British Legation to massacre women, children and native Christians. This made it absolutely necessary that they should be driven out. The fire was got under [control], and a portion of the Hanlin was occupied by the defending force."

The Graphic, October 13, 1900

[graphic_1900_049]

|

|

|

| |

“The Siege of the Peking Legation:

the Arrival of the Head of the Relief Column.

All the buildings near the Legation bear witness to the severity of the fire of the Chinese. In the houses adjoining the Legation, several tiers of loopholes had been pierced, and through these a continuous fire was poured during the siege. Three thousand shells were fired by the Chinese. Fortunately, most of them were fired too high and the aim was wild. The meeting of the besieged with the relieving troops gave rise to a scene of wild enthusiasm, men and women cheering and shaking hands with officers, soldiers, and camp followers—with anyone, in fact, who came along. The first to arrive of the relieving column were Major Scott and four men of the 1st Sikhs.”

The Graphic, October 13, 1900

Artists: W. Hatherell, R.I., & Frank Craig,

from a sketch by Captain F. G. Poole

[graphic_1900_048]

|

|

|