| |

This chapter gives an overview of the Second Opium War (1856–1860) in the form of a timeline, with imagery drawn mainly from the British Illustrated London News and the French publication, L’Illustration.

1856

February 29, 1856: Execution of a French Missionary

The French missionary, Father Auguste Chapdelaine, is arrested in December 1855 while traveling in Guangxi province, a restricted area. Accused of preaching a prohibited faith, he is tortured and killed. The incident eventually leads France to join Great Britain in an Anglo-French military alliance against China.

October 8, 1856: Chinese Authorities Seize the Arrow

Port officials in Canton (Guangzhou) harbor board the Arrow—a small boat that claimed British registration—on suspicion of piracy. The Chinese haul down the boat's ensign and arrest the crew. The British claim their flag has been insulted. More importantly, the arrests appear to violate the 1842 Treaty of Nanking, signed after the first Opium War (1839–1842). Within weeks, the “Arrow incident” is used by Britain as a pretext for attacking Canton. Their aim is to force the Qing court into a favorable renegotiation of the 1842 treaty, thereby gaining trade and other concessions.

October 23, 1856: Britain Attacks – U.S. Lands in Canton

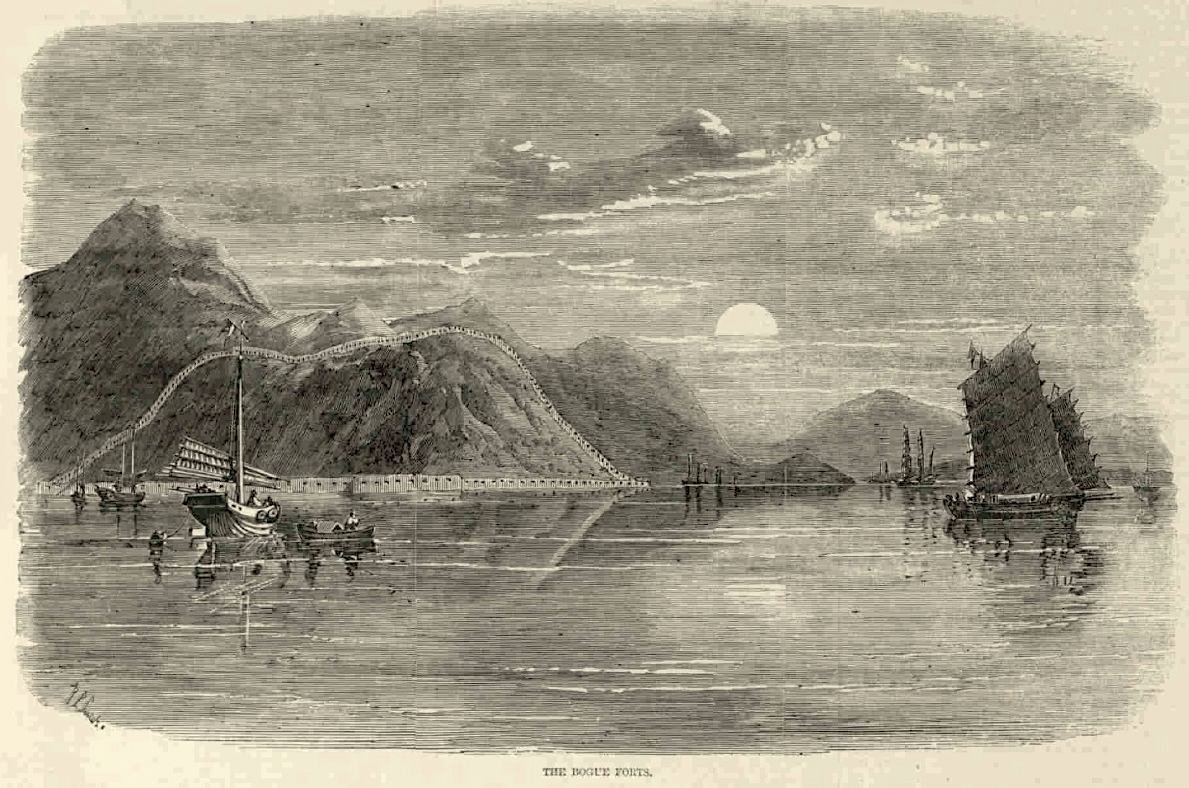

Rear-Admiral Sir Michael Seymour leads British warships up the Pearl River estuary to engage the Boca Tigris forts that protect Canton. Many of the Chinese forts are subdued by bombardment, seized, and burned. |

|

|

| |

“The Boque Forts.” (Boca Tigris Forts)

Illustrated London News, January 10, 1857 (p. 4)

Illustrated London News Group

[ILN_1857-01-10_04_boque-forts_BL.jpg]

|

|

| |

At the same time, about 80 American officers, sailors, and marines from the sloop-of-war USS Portsmouth land unopposed in Canton. Acting at the request of Consul Oliver H. Perry, they take positions on rooftops to guard the American factory (warehouse) district. The foreign factories were all located outside of Canton's city walls.

|

|

| |

Translated from French:

“Factory Street, in Canton. — After a Sketch by Mr. A. Borget.”

The foreign factories that lined the Canton waterfront

were easily recognized by their nations' flags.

L'illustration, Journal Universel, Paris,

May 15, 1858 (p. 309)

University of California

[illustration_1858-05-15_309_canton]

|

|

| |

October 24, 1856: British Secure Factories

Royal marines occupy the British districts, and gunships easily seize Chinese defenses that could threaten the factories. Many of the foreign merchants flee.

October 25, 1856: British Warships Blockade Canton

After capturing all of Canton's defenses, Admiral Seymour sends Commissioner Ye (Ye Mingchen, governor general of Guangdong and Guangxi) a message: trade will resume when Ye agrees to negotiate. Ye sends no reply.

|

|

| |

October 27, 1856: Bombardment of Canton

In the morning, a fresh ultimatum is issued but there is still no reply. At 1:00 pm British ships begin the bombardment of Canton by destroying Ye's official residence. Attacks like this continue through November, but the British fail to breach the city walls or enter Canton.

|

|

| |

Translated from French:

“Plan of the Bombardment of Canton by English Ships.”Bombing of Canton:

We receive from an eyewitness the account of the deplorable events which have just bloodied the city and the surroundings of Canton: the character of our correspondent is for us a guarantee of his perfect truth. (L'illustration, Journal Universel, Paris, January 10, 1857 (p. 17)

University of California

[illustration_1857-01-10_017_canton]

|

|

| |

November 15–22, 1856: U.S. Destroys Boca Tigris Forts

On November 15, a Boca Tigris fort fires on American boats in the Pearl River. In retaliation, U.S. forces destroy four of the five forts between November 20–22.

December 1856: Factories Burned in Canton

The few remaining merchants—Chinese and foreign—are driven from the city when the factory districts are burned, presumably by the Chinese. There are many skirmishes, and both sides commit aggressions. The Illustrated London News presents a full-page illustration of the fires with the following account, putting the blame on the Chinese, despite Ye’s claims that it was the British:You will have heard how the factories were burned, and how the Viceroy Yeh had the audacity to charge the English with having themselves caused the conflagration, and that he actually wrote a letter of expostulation, showing plainly enough that he knew “a day of reckoning” would come sooner or later. … Although driven from their homes, the Cantonese merchants behaved in an admirable way, encouraging the Admiral and strengthening his hands as far as they could. … (Illustrated London News, March 14 1857, p. 251) |

|

| |

“Canton and Part of the Suburbs, Sketched During the Conflagration of the City“

Illustrated London News, March 14, 1857 (p. 250)

Illustrated London News Group

[ILN_1857-03-14_250_canton-burns_yale]

|

|

| |

1857

Early 1857: U.S. & China Agree on Neutrality

The November destruction of the Boca Tigris forts by the Americans results in an agreement with China, keeping the U.S. out of the conflict. Both sides honor it, until U.S. warships participate in the June 1859 attack at Dagu (Taku).

January 8–17, 1857: British Forces Leave Canton

Lacking a clear military objective and short of men, the British commanders in Canton decide to retreat down the Pearl River to the Portuguese colony of Macao.

The harrying tactics of the Chinese, who seldom left the squadron alone for many hours together, annoying it almost every night with rockets, fire rafts, and all sorts of devilments, led Rear-Admiral Seymour to doubt the possibility of keeping the river communication open with the small force at his disposal; and, learning from India that no troops could be spared thence, he was disposed partially to withdraw from his position. … it was finally determined to hold Macao Fort, and to keep at least the lower reaches of the river open. (Clowes, William Laird. The Royal Navy, A History From the Earliest Times to the Death of Queen Victoria, vol. vii. London, Sampson Low, Marston & Company 1903, pp. 93-136.)

March 3, 1857: Parliament Votes Against China War

Prime Minister Palmerston advocates new military action against China, but the House of Commons considers the attack on Canton unjustified. Member of Parliament Nicholas Kendall points out: “The hostile acts committed by Admiral Seymour … could not be justified on the plea of necessity, and were worthy of the heaviest censure.”

April, 1857: New Government Reverses Course

After a snap election, Palmerston has the votes in Parliament to defeat what he calls the “anti-English” opposition. Britain invites the U.S., Russia, and France into an alliance against China. Only the French—who stand to gain from renegotiating the 1842 treaty—accept, using the execution of Chapdelaine as the cause. The Anglo-French alliance becomes central to British war plans in China.

May–November, 1857: Allies Plan Joint China Expedition

The Illustrated London News reproduced from a photograph a scene of British troops mustered in Malta preparing for the campaign in China, which is described in patriotic tones:

The War in China. We have to thank Captain Inglefield, R.A., for the original of the accompanying Illustration, a photograph, taken by him of the garrison of Malta, when upwards of 7000 troops were reviewed by Sir John Pennefather, K.C.B., in the presence of Major-General Ashburnham, and Major-General Garrett, and staff en route to China. … The parade of so large a body of fine troops beneath the walls of the noble fortress is a scene of no ordinary interest. (The London Illustrated News, Supplement, May 16, 1857, p. 471)

By October, Allied war planners decide that Anglo-French forces will first re-take Canton, then attack Beijing.

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

“Sir John Pennefather, K.C.B., reviewing the troops in the presence of Major-Generals Ashburnham and Garrett, on their way for the China

Expedition—from a photograph.”

The Illustrated London News, Supplement, May 16, 1857 (p. 471)

Visualizing Cultures

[co2_ILN_1857_0516_471s_pg_b ]

|

|

| |

May 10, 1857: Indian Uprising Begins

In India, an uprising against the British East India Company preoccupies Great Britain for most of 1857. Britain's control of India will not be fully regained until the following year.

June–July, 1857: China War Delayed

In June, High Commissioner Lord Elgin (James Bruce, son of Thomas “Elgin Marbles” Bruce), learns of the uprising in India: he diverts many reinforcements intended for China to the uprising. On July 15th, Admiral Seymour orders two warships with 300 marines aboard from China to Calcutta (Kolkata). By November the British will have held down the “mutiny” well enough to send a large force from India to join the war in China.

The French also suffer logistical problems. In July, Minister-in-Command Baron Gros is ordered to China to meet with Lord Elgin, but Gros will be delayed until October. The French naval squadron will not reach the mouth of the Boca Tigris until December 10th, too late to take part in the blockade of Canton.

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Translated from French:

“Mooring of the French division in the Boca Tigris, December 11, 1857. — From a Sketch Sent by Mr. Deslandes.”

L'illustration, Journal Universel, Paris, February 6, 1858 (p. 82)

University of California

[illustration_1858-02-06_082_macau]

|

|

| |

December 10, 1857: British Warships Blockade Canton

On December 10, Canton is blockaded. New demands are made, among them compensation for the Arrow incident and the murder of Chapdelaine. Commissioner Ye refuses. Hesitant to be the bearer of bad news, he writes to the emperor and assures him that things are under control: “The English barbarian is now begging us for peace, trading should be allowed to resume soon.”

December 28–29, 1857: Anglo-French Forces Enter Canton

On the morning of December 28, the city is bombarded by British and French warships. Allied troops land about two miles from Canton. The following morning, they bring ladders to the city wall: the French beat the British over the ramparts by minutes. The north-east gate is opened and the main city is occupied. On December 30, flags of truce appear but Ye refuses to discuss terms with the Allies.

|

|

|

| |

Translated from German:

“Conquest and Bombardment of Canton in China, by the English and French Army, December 28, 1857”

Published by Carl Lanzedelli, Vienna, ca. 1859

Anne S.K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library

[1857_12-28_conquest-canton]

|

|

| |

1858

January 5, 1858: Allies Abduct Chinese Officials

At daybreak in Canton, French troops capture the Tartar general Muh, while the British kidnap the governor and Ye, who is designated as a prisoner of war. The general and the governor are released: both agree to help the Allies maintain order in Canton, and the blockade is lifted on February 10. Ye dies imprisoned at Fort William in Calcutta in 1859.

|

|

| |

1858–1861: Anglo-French Occupation of Canton

|

|

|

| |

April 14, 1858: Lord Elgin Arrives—China Plays for Time

Lord Elgin anchors his squadron in the mouth of the Peiho River (Hai He) on April 14th. After meeting with a local commissioner, Elgin decides the Chinese aren't serious about negotiating. Allied warships prepare to attack the Dagu forts that guard access to Beijing.

May 16, 1858: Russia & China Accord on Manchuria

In the 1858 Treaty of Aigun, China cedes to Russia over 600,000 square kilometers (231,660 square miles) of Manchuria (north-east China). The treaty stipulates that only Russian and Chinese vessels will be permitted to navigate certain rivers. It takes until 1860 for China to ratify the treaty, which it does in exchange for Russian diplomatic intercession at the end of the Second Opium War.

May 20, 1858: Allies Take Dagu Forts, Threaten Beijing

British forces under Lord Elgin, backed by French troops, capture the Dagu forts. They destroy many of the forts and river defenses, exposing Beijing to attack.

|

|

| |

June, 1858: China Signs the Treaties of Tianjin

|

|

| |

November 8, 1858: China Legalizes Opium Trade

Further negotiations legalize importation of opium, with an 8% tariff. The British support legalization in order to regulate the trade: at the time, opium is legal and sold openly in Britain. China gives in. A Chinese commissioner later explains,China still retains her objection to the use of the drug on moral grounds, but the present generation of smokers, at all events, must and will have opium. (Friend of China. The Organ of the Society for the Suppression of the Opium Trade, vol. xi, no. 3, July 1889. London, Samuel Harris & Co.)

|

|

| |

Chinese Opium Smokers

Illustrated London News, September 20, 1858 (p. 483)

Illustrated London News Group

[ILN_1858-11-20_483_opium_BL]

|

|

| |

November 9, 1858: British Reconnaissance Mission in the Yangtze

To ascertain the state of the interior, Lord Elgin commands a two-month fact-finding mission up the Yangtze (Chang Jiang) River. There are altercations, including a two-day bombardment of the forts at Nanking (Nanjing), sparked by a cannon fired at the British by mistake.

|

|

| |

Translated from French:

“Passage of the Two Pillars in the Yang-tze-kiang.”

Leaving Shanghai on November 9, the squadron of three steamers and

two gunboats went up the Yangtze as far as Hankow (Wuhan).

L'illustration, Journal Universel, Paris, March 12, 1859 (p. 161)

University of California

[llustration_1859-03-12_161_yangtze]

|

|

| |

1859

June 25, 1859: Hostilities Escalate – Chinese Victory at Dagu

When British and French envoys are sent to exchange treaty ratifications in Beijing, they find the Pieho River defenses—destroyed in 1858—have been rebuilt and improved, making the river impassable. Demands for free passage go unanswered and on June 25, British gunboats and a landing force of 350 royal marines attack the Dagu forts, the second such attack in the war. Having underestimated the strength of Chinese forces, they're driven back, losing three ships and taking many casualties. The incident fuels animosity on both sides, and stiffens the resistance of the Qing court.

|

|

|

| |

Translated from French:

“Surprise, by the Chinese, on the Pie-Ho River, of the Allied Fleet Conducting Ambassadors from France and England to Pekin.”

Spurious reports of an attack on the diplomatic mission, like this one in L'illustration, were often repeated as fact.

L'illustration, Journal Universel, Paris, September 24, 1859 (p. 228)

Hathi Trust Digital Library

[illustration_1859-09-24_228_surprise-peiho]

|

|

| |

November 13, 1859: France Appoints a Commander-in-Chief

General Cousin Montauban is selected as French commander-in-chief of the China expedition by Napoleon lll, who later grants him the title of Comte de Palikao (after the Battle of Palikao).

|

|

| |

Translated from French:

“General Cousin Montauban, Commander-in-Chief of the French Expeditionary Force sent to China. From a photograph by Mr. Moulin.”

University of California

[illustration_1859-12_36a525]

|

|

| |

Late 1859–mid 1860: Allies Move Resources Into Place

|

|

| |

1860

February–May 1860: War Photographer Felice Beato Joins the Expedition

Finished with documenting the uprising in India, Felice Beato sails from Calcutta on February 26 with General Sir Hope Grant, commander of the British army in China. They arrive in Hong Kong on March 13. Beato soon befriends Charles Wirgman, a sketch artist for the Illustrated London News. Bored with waiting, on May 20 they are at last berthed on a British troop transport heading toward Beijing.

|

|

| |

June 5, 1860: Allied Commanders Embark for China

Lord Elgin and Baron Gros leave Ceylon (Sri Lanka) for China on the mailboat Pekin. |

|

| |

Translated from French:

“Lord Elgin and Baron Gros leaving Ceylon for China on Board the Mailboat Pekin, June 5, 1860. From drawings sent by Mr. F. L. Roux.”

L'illustration, Journal Universel, Paris, July 14, 1860 (p. 17)

University of California

[llustration_1860-07-14_017_cover-ships]

|

|

| |

August 14–21, 1860: Anglo-French Forces Re-Capture Dagu Forts

|

|

| |

August–September 1860: Allies Advance – Chinese Imprison Negotiators

After garrisoning the forts, British and French troops march upriver toward Beijing—each nation on opposite banks of the Peiho. The Chinese agree to talks, but then ambush the Western negotiators and imprison them in Beijing.

|

|

| |

September 18, 1860: Large Chinese Force Routed

Reaching Chang-Kia-Wan (Zhangjiawan), Allied troops meet a 30,000-strong Chinese army, said to be five miles wide, and quickly defeat it. Qing commander-in-chief Senggerinchen decides his remaining cavalry will make their last stand at the Tonghui River, eight miles from Beijing.

September 20, 1860: Anglo-French Forces Invade Beijing

|

|

| |

October 6, 1860: Capture & Looting of the Yuanmingyuan

|

|

| |

October 11, 1860: Beijing Truce Declared

Demands for the release of the captured negotiators having failed, British engineers prepare to demolish the walls of Beijing. At 11:30 pm the two sides agree to a truce, and the Chinese open the city gate. |

|

| |

Translated from French:

“Entry of the Allied Troops Into Pekin by the Tchao-yant Gate, October 22, 1860.”

The pitched battle portrayed in L'illustration may have been dramatized, or repurposed from other events. Agreeing to a truce, Prince Gong opened the Andingmen gate: Allied forces remained camped outside the city walls or in the Andingmen. (Beato took the first photographs of Beijing from atop the gate.)

L'illustration, Journal Universel, Paris, December 2, 1860 (p. 412)

University of California

[illustration_1860-12-02_412_pekin-22Oct]

|

|

| |

October 18–19, 1860: Yuanmingyuan Destroyed on Elgin's Command

Upon learning that some of the imprisoned negotiators are dead, Lord Elgin considers the destruction of the Yuanmingyuan, “not for vengeance, but for future security.” At a meeting with Baron Gros, he claims some prisoners were tortured there:

To this place [the emperor] brought our hapless countrymen, in order that they might undergo their severest tortures within its precincts. Here have been found the horses and accoutrements of the troopers seized, the decorations torn from the breast of a gallant French officer, and other effects belonging to the prisoners. (Letters and Journals of James, Eighth Earl of Elgin. London, 1872, pp. 365-366)

Gros demurs, but doesn't stand in Elgin's way. On October 18–19, British troops led by Hope Grant demolish and burn most of the roughly 200 palaces, gardens, and pavilions.

October–November 1860: Second Opium War Ends

| |

|