On September 1, 1923, a devastating earthquake struck the Kantō plain where Tokyo and Yokohama are located, causing fires that created a windstorm that in turn propelled a raging conflagration. On September 1, 1923, a devastating earthquake struck the Kantō plain where Tokyo and Yokohama are located, causing fires that created a windstorm that in turn propelled a raging conflagration.

Enormous portions of the two great cities were destroyed. As many as 140,000 people are estimated to have perished, and more than two million were made homeless. |

|

| |

A little more than two decades later, on March 9, 1945, as the U.S. war with Japan entered its endgame, the U.S. Army Air Forces introduced a new tactic of aerial bombardment in a nighttime raid on Tokyo. Over 300 four-engine B-29 bombers were sent in at low altitude and dropped incendiary bombs that destroyed—in a matter of hours—over 14 square miles of the most densely populated city in the world. The number killed in this single air raid was around 130,000, and again over two million were made homeless. In the weeks and months that followed before Japan’s surrender in mid-August 1945, Tokyo (and 65 other Japanese cities) were subjected to an ongoing campaign of firebombing. At war’s end, the capital city was mostly rubble.

Among the many things that the war and obliteration bombing destroyed was memory of the exuberant rebirth of Tokyo that took place after 1923. The earthquake was a catastrophe—but also the occasion for massive reconstruction in modern, up-to-date ways. “New Tokyo” became a catchphrase of the time. Imposing structures of steel and stone were one manifestation of this. Mass transit including a subway system was another. Yet another manifestation of rebirth was the emergence of vibrant inner-city districts devoted to governance, commerce, and entertainment. After the earthquake, Tokyo began to emerge as one of the world’s great cosmopolitan cities.

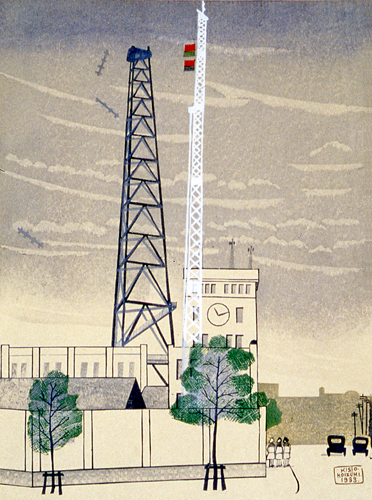

One of the most graphic celebrations of this modern metropolis took the form of woodblock prints by an innovative generation of artists influenced by Western individualism and expressionism. Their creations were known collectively as “creative prints” (sōsaku-hanga); and, for anyone who loves history, one of the most invaluable contributions of these artists to our ability to imagine the city reconstructed after 1923 only to be pulverized again in 1945 was the creation of not one but two print sets offering “100 views” of the “new Tokyo.” These visions of the city are reproduced and analyzed here.

* * *

“Tokyo Modern — I” introduces the “100 Views of Great Tokyo in the Shōwa Era” created between 1928 and 1940 by printmaker Koizumi Kishio. An accompanying “visual narrative” here enables viewers to explore 18 thematic pathways—digital city tours, if you will. This introduction provides a scholarly guide to Koizumi’s opus and draws out tensions and undercurrents in his ostensibly modern city—including the pull of the past, the pervasive imperial presence, and the growing intrusion of militarism.

“Tokyo Modern — II” is a complete gallery of Koizumi’s famous series, including all revised scenes (thus totaling 109 prints in all). Included here are the cryptic annotations Koizumi provided for the series after it was completed in 1940.

Between 1928 and 1932, eight other woodblock artists working in the “creative prints” mode also produced a subscription series titled “100 Views of New Tokyo.” The variety of their styles, as well as the urban scenes they chose to depict, complement Koizumi’s renderings to enhance our appreciation of the dynamic sense of cosmopolitan rebirth that prevailed in the wake of the earthquake. The complete set by these eight artists is also made accessible for the first time here, in “Tokyo Modern — III.”

“Modernity” and its contradictions is a subject of great comparative interest, and “Tokyo Modern” can help us rethink both modernization and our various roads to war. At the same time, these graphics provide a rare window on the dynamic baseline to the “postwar Japan” we too often isolate from its prewar and wartime past.

|

|

|

| |

EARTHQUAKE & AFTERMATH

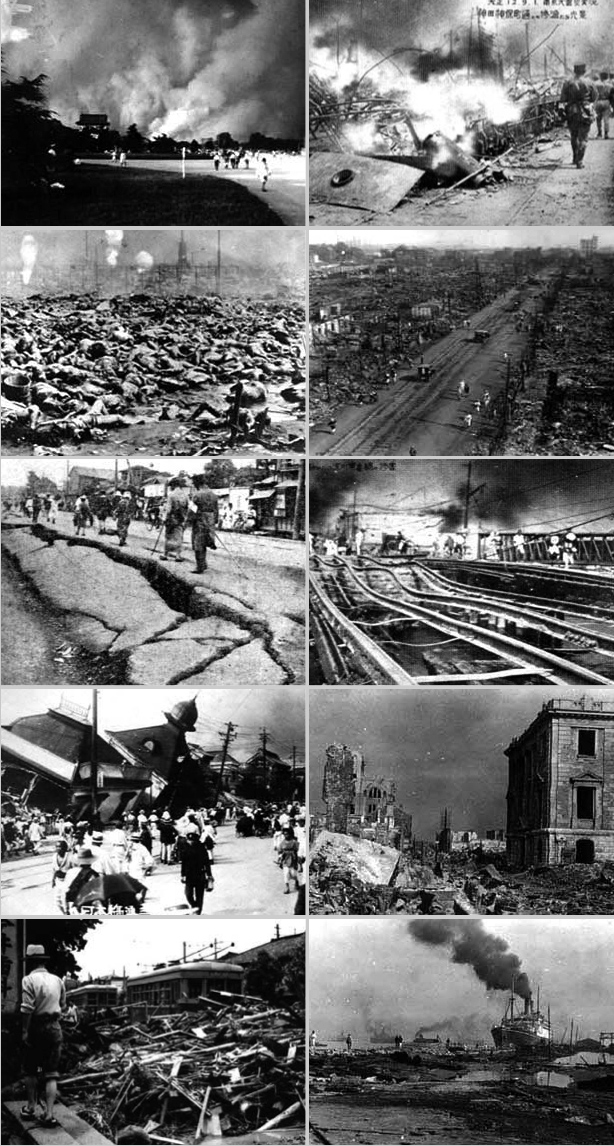

At 11:58 am on September 1, 1923, an earthquake struck eastern Japan with devastating force, completely incapacitating Tokyo and Yokohama, Japan’s primary port city. The earthquake struck just as charcoal and wood-burning stoves were being stoked to prepare for the noon meal. A comparatively small percentage of the destruction was actually caused by the tremor. Fire, propelled by what would otherwise have been a welcome breeze and fuelled by the wood structures that filled the congested metropolis, caused most of the devastation. The intense heat consumed nearly all of the existing oxygen and created a bizarre sequence of windstorms that only accelerated the destruction. Planned firebreaks, in the form of parks and boulevards, were virtually nonexistent. Official estimates put the number of deaths at 104,619, over 90 percent of them in Tokyo. Approximately 70 percent of the metropolitan population of 2,265,000 was left homeless.

Municipal and national governments were ill-prepared to respond to this catastrophe, and declaration of martial law was virtually the first reaction. The earthquake almost immediately exposed the raw social tensions of the period. Many citizens were only too willing to give credence to rumors that resident Koreans were poisoning water sources and torching buildings. Military police and vigilante groups used the cover of chaos to eliminate union organizers, communists, socialists and all brand of left-of-center radicals. On September 16, police arrested the prominent radicals Osugi Sakae (1885–1923) and his wife, Itō Noe (1895–1923). They were taken to the Kameido police station and killed. Within the first few weeks of September the opportunistic purging of unwanted ethnic and political elements resulted in an estimated 6,000 deaths.

|

|

Photos of the Earthquake Aftermath

Destruction caused by the Great Kantō Earthquake

that devastated Tokyo and Yokohama on September 1, 1923

Photographs by August Kengelbacher

|

| |

On December 28, 1923, four months after the earthquake, Namba Daisuke (1899–1924) joined a crowd at the Toranomon intersection awaiting the motorcade of Prince Regent Hirohito, who was to open a new session of the parliament. Namba, a radical harboring grievances over government suppression of nonconformist views and, most immediately, outraged by the murder of so many Koreans and radicals in the wake of the earthquake, fired a pistol at the prince. The shot missed its mark, but the incident—ultimately concluding with Namba’s execution—shook the nation. The assassination attempt provided impetus for passage of a Peace Preservation Law on February 19, 1925. This law laid the foundation for subsequent legislation and regulations that would formalize official intolerance for dissenting ideologies.

Thus, the maelstrom of the Kantō earthquake provided two crucial elements that, in the ensuing several decades, would lead to the construction of an “imperial capital”: (1) a fire-cleansed canvas upon which a new city could be constructed, and (2) the legal/ideological methods for structuring an urban and political landscape amenable to an evolving imperial ideology that was premised on ancient myths and traditions but, at the time of the earthquake, was in reality less than 50 years old—dating back only to the Meiji Restoration of 1868.

There is an abundance of textual and visual documentation about the earthquake and subsequent reconstruction of Tokyo—a process that was most evident during the 1930s. Central to recovery was a secure source of natural resources, most readily available in the northeastern Chinese territory of Manchuria. Ensuring such access became a development parallel and not unrelated to reconstruction at home, leading to increased Japanese militarism and eventually war.

|

|

|

| |

One section of a 12-part Kantō Earthquake Scroll, 1925

by Nishimura Goun

Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution F1975.12

|

|

| |

The long journey from Tokyo’s earthquake-devastated landscape to a city reordered, rebuilt, and renewed, was narrated in official literature as a kind of “march of progress,” a sequence of mercantile successes and modernizing projects. Yet, contrary news—resistance and war in China, political assassinations at home—gave Japanese reason to view the newly formed city and its outlying empire with some skepticism. And beneath the vicissitudes of daily life the earthquake had left a permanent memory scar that quietly mocked optimism. Living in the new city required adjustment to changed configurations, different points of emphasis, and, most importantly, resetting awareness of the places that conveyed a sense of identity and stability.

|

|

|