[kk9012_1925_Goun_QuakeScroll]

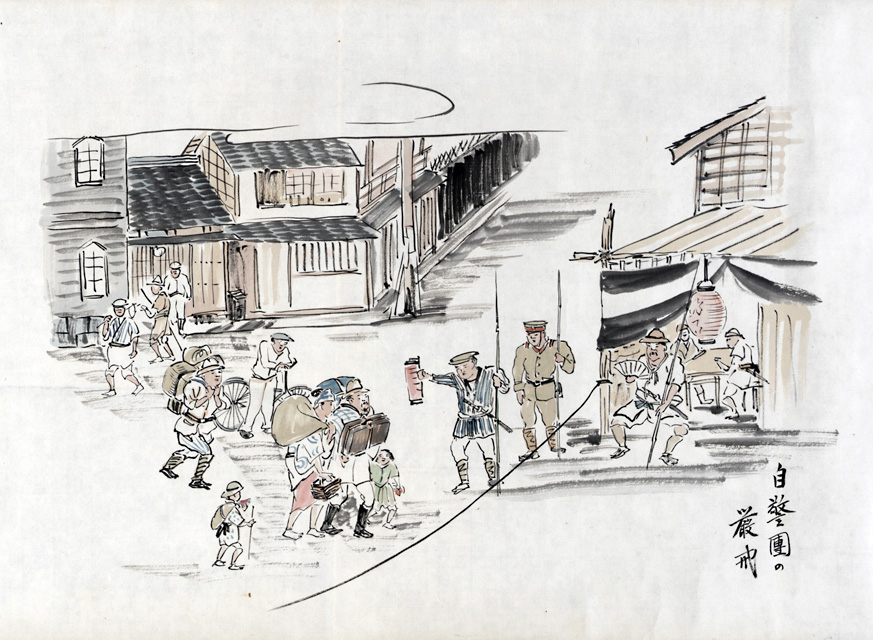

11. Jikeidan no genkai

(Self defense forces on high alert)

[kk9011_1925_Goun_QuakeScroll]

10. Gissha teitei (?) toshite shodo wo iku

(Oxcarts go one after another on a burned out field)

[kk9010_1925_Goun_QuakeScroll]

9. Romei wo tsunagu genmaimeshi

(Surviving by eating brown rice)

[kk9009_1925_Goun_QuakeScroll]

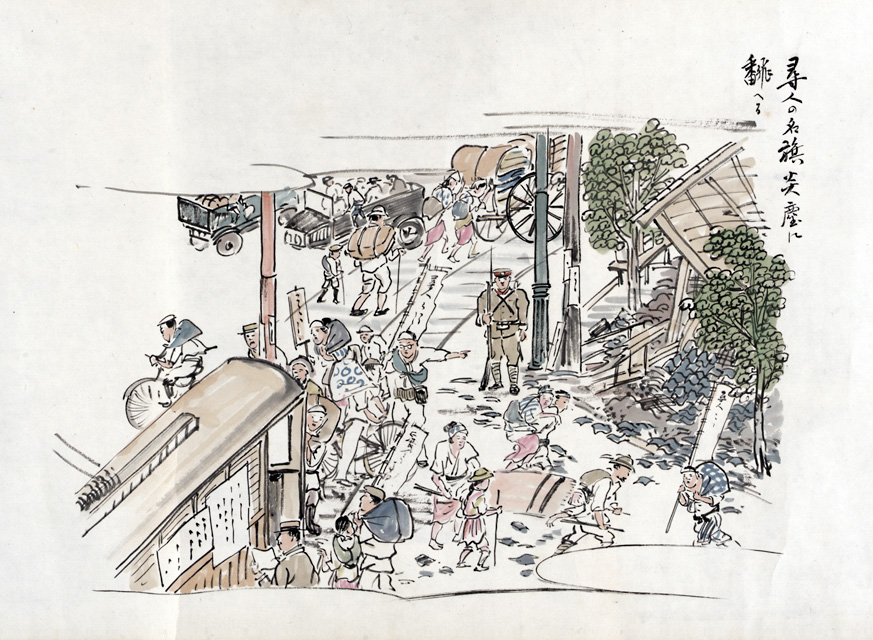

8. Tazunebito no meiki enjin ni hiruga’eru

(Name flag identifying those yet unaccounted for waves in the ashes)

[kk9008_1925_Goun_QuakeScroll]

7. Kyo’en Azumabashi ni semaru

(Blaze getting closer to Azuma bridge)

[kk9007_1925_Goun_QuakeScroll]

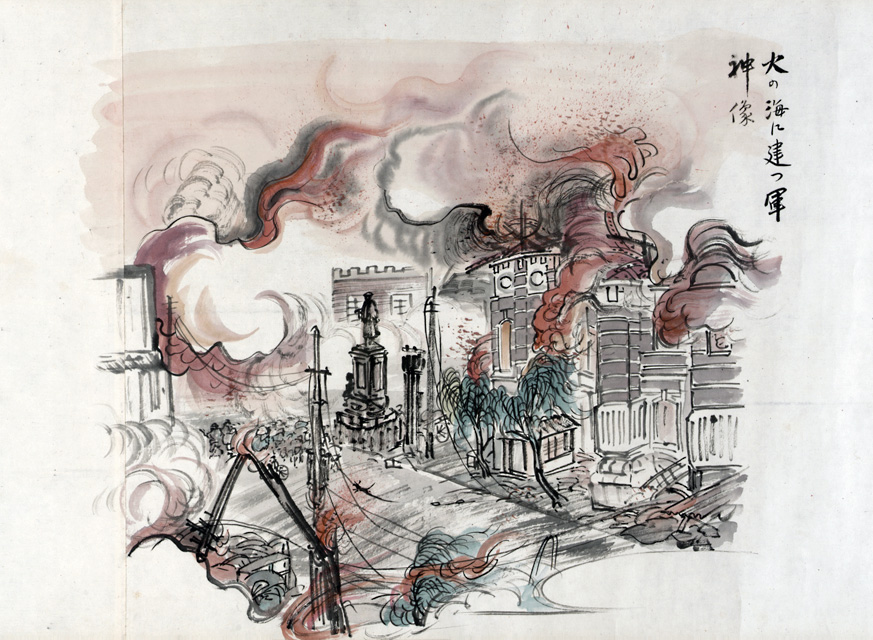

6. Hi no umi ni tatsu gunjin-zo

(Statue of a military figure stood in the blazing inferno)

[kk9006_1925_Goun_QuakeScroll]

5. Mouka Ginza gaitou wo osou

(Blaze attacking Ginza streets)

[kk9005_1925_Goun_QuakeScroll]

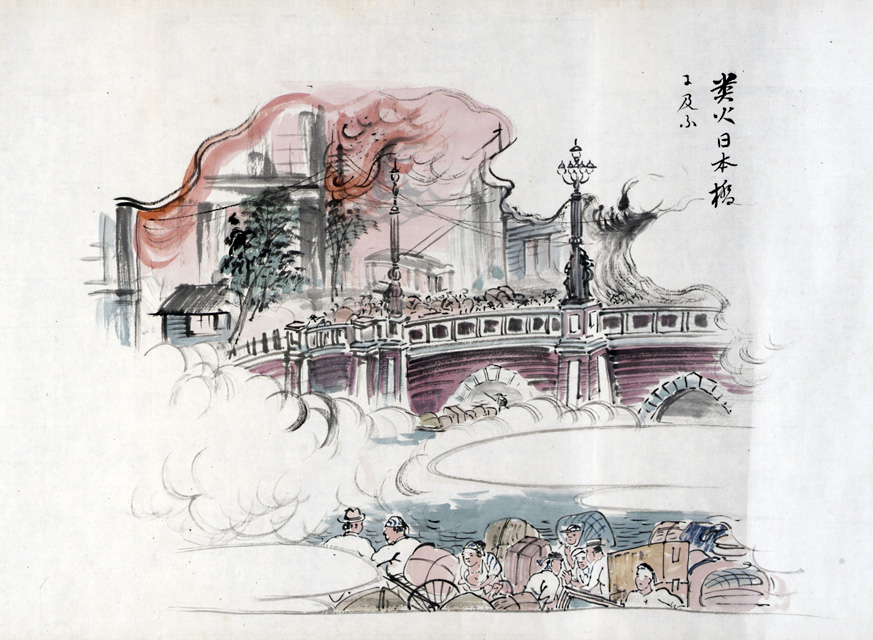

4. Gouka Nihonbashi e oyobu

(Flames reaching Nihon bridge)

[kk9004_1925_Goun_QuakeScroll]

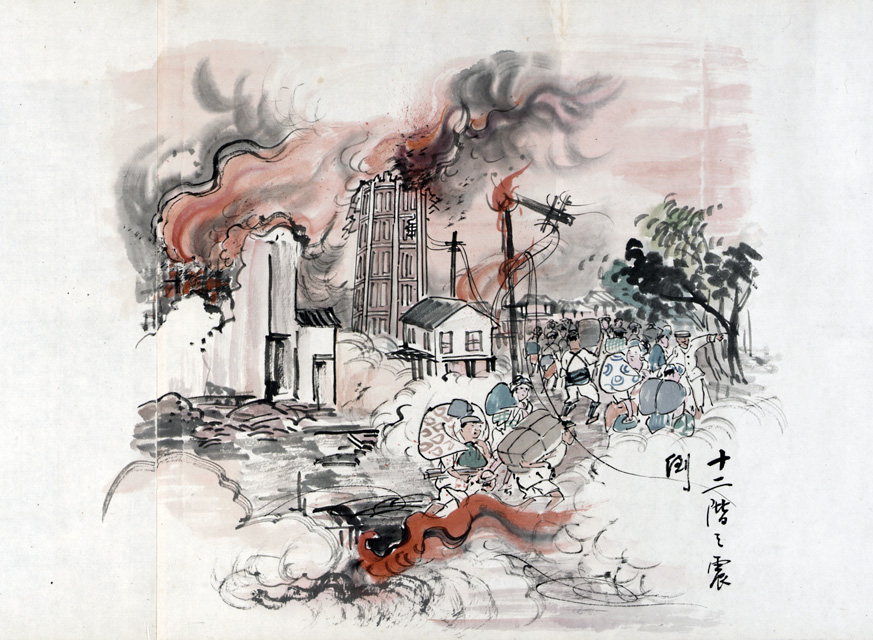

3. Juni-kai wo (?) shinto

(The Junikai Building is collapsed by earthquake)

[kk9003_1925_Goun_QuakeScroll]

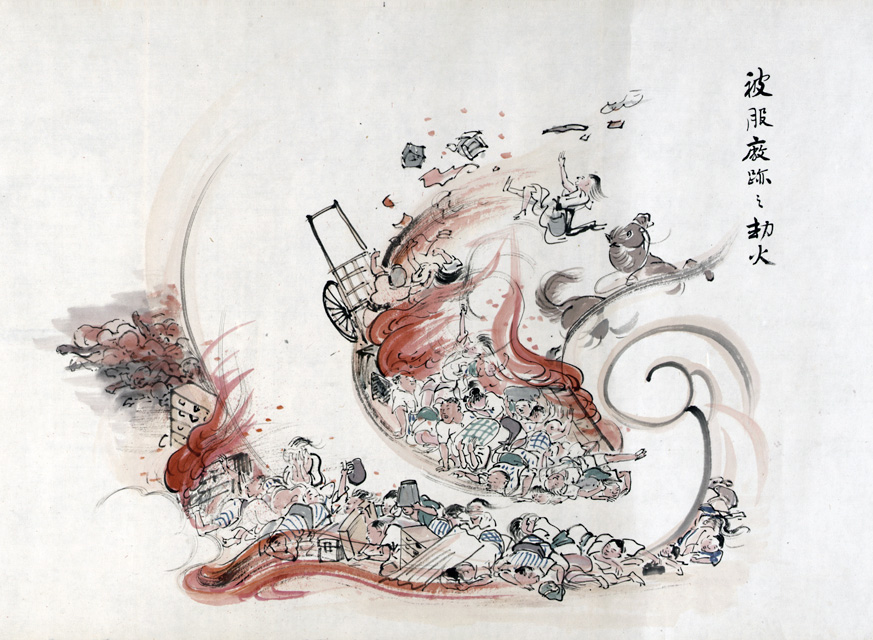

2. Hifukusho-ato to Kouka

(Military clothing factory and devouring flames)

[kk9002_1925_Goun_QuakeScroll]

1. Asakusa Kanze’on no Reiken

(Appearance of the spirit at Asakusa Kanze’on)

[kk9001_1925_Goun_QuakeScroll]

Scenes of the 1923 Earthquake,

by Nishimura Goun, 1925

Japanese scrolls are read right-to-left.

Nishumura Goun (1877–1938) was a student of the great Kyoto painter Takeuchi Seiho (1864–1942). Seiho is credited with advancing into modern times a style of lyrical realism developed by the painter Maruyama Okyo (1733–95). A mixture of closely observed, almost scientifically accurate detail, blended with a soft atmospheric quality, is a major generalized feature of the style.

Goun’s handscroll rendering of earthquake scenes is dated to 1925. It is difficult to imagine that he was an eye witness to the conflagration. More likely, he had access to photographs and other accounts of the disaster, and constructed scenes with a mixture of fact and imaginative flair. Goun’s style of representing human figures in almost doll-like form seems to diffuse and distance the sheer terror of the event. Similarly, the titles that he offers for the scenes have a poetic rather than precise flavor. Occasionally he uses terminology that has Buddhist nuance. Indeed, the rendering of flame-filled devastation recalls depiciions of hell found in ancient Buddhist handscrolls.

Scenes of the 1923 Earthquake,

Nishimura Goun, Japanese, Taisho era, 1925

Handscroll, color on paper, 32.8 x 560.9 cm

Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C