|

| |

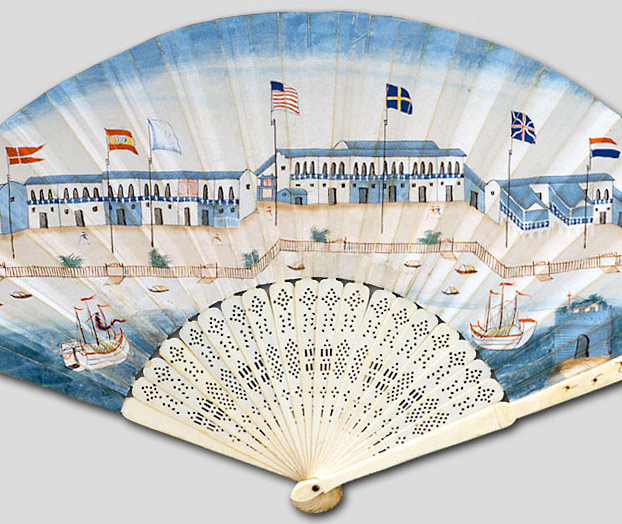

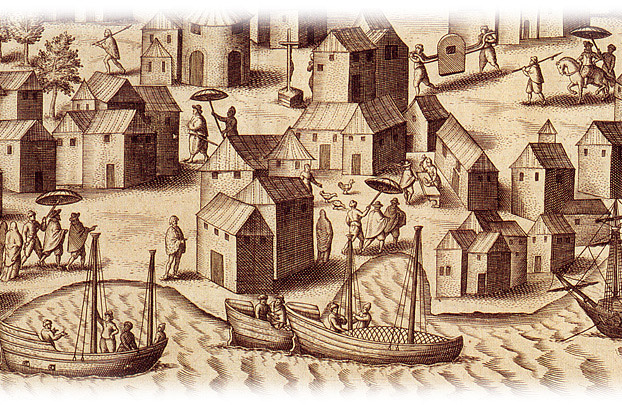

Canton, where the business of trade was primarily conducted during this period, is depicted on this fan created for the foreign market. Seven national flags fly from the Western headquarters that line the shore.

Fan with Foreign Factories in Canton, 1790–1800

Peabody Essex Museum [cwOF_1790c_E80202]

MACAU, CANTON, HONG KONG

From early times China engaged in extensive trade relations with other countries, and until the mid 19th century Chinese officials directed by the imperial court in Beijing dictated the conditions under which such trade was conducted. From the 16th century to mid 1800s, three cities became the centers of the trading system linking the “Middle Kingdom” to Western European powers and eventually the United States: Macau, Canton, and Hong Kong.

Macau was under Portuguese control from 1557 to 1999. From the late 1700s the center of Western trade activities shifted upriver to foreign quarters at Canton (Guangzhou), which remained under the tight regulation of Chinese authorities. The so-called Canton trade system reflected the strength of the Chinese state at the height of the Manchu-led Ching dynasty (1644–1911); and the collapse of this system in the mid 19th century marked the beginning of the long decades of China’s decline and humiliation as a great power.

Two factors in particular precipitated the end of Chinese control over trade with the West. One was opium, which the Western powers began smuggling into China to compensate for a paucity of other exports. The other was naval technology epitomized by the emergence of Western steam-powered vessels deployed as both merchant ships and warships. The collapse of the Canton system was marked by the Opium War of 1839 to 1842, in which the British defeated the Chinese under the banner of free trade and forced them to legalize opium imports, open new ports to trade, and agree to a low fixed tariff.

In the wake of the Opium War, Canton carried on as a trading port but British commercial interests in particular were extended elsewhere—most dramatically to the newly acquired harbor at Hong Kong. Hong Kong became not merely a symbol of the new era of “free trade,” but a bona-fide British colony—arch-symbol indeed of the new era of China’s loss of autonomy.

In Western eyes, the Canton trade system became the source of a romanticized image of both Western commercial activity and China itself. Fine examples of Chinese art and luxury items—porcelain, lacquer, silk, and furniture—were prized in upper-class circles in Europe and the United States. Tea became a favorite import in the West. And at the same time, foreign merchants commissioned both Western and Chinese artists to provide a visual record of their own involvement in the China trade.

This export art provides the visual flesh and bones of this unit and enables viewers to see the China trade as the foreign traders themselves wished it to be seen by their contemporaries by home and remembered by later generations. There exists no counterpart visual record for domestic consumption on the Chinese side. The foreign enclaves seemed marginal to Chinese at the time; there was no domestic market for viewing outsiders; there was indeed as yet no technology of mass reproduction. Photography still lay ahead.

What we encounter in these visuals, in short, is the Canton trade system as portrayed largely through (and for) the eyes of the non-Chinese—colorful, romantic, sometimes exotic, often heroic, and exceedingly incomplete.

|

|

|

| |

Trade with the West

From 1500 to 1800, the great empires of Europe and Asia expanded across the world, conquering new territories and intensifying their internal and external trading networks. We know best the story of the European expansions into the New World, India, and Southeast Asia, or Russia’s conquest of Siberia, but China’s armies, settlers, and traders also penetrated distant regions, extending market networks and creating increasingly dense populations on the frontiers. Under the Ming and Qing dynasties, the Chinese empire reached a new peak of population and expanded its territory to an unprecedented degree. The Ming dynasty (1368–1644) in the 16th century held off Mongol raids in the northwest while expanding military garrisons in the southwest. In addition, large numbers of Chinese moved into Southeast Asian countries, rising to become the dominant commercial forces there. The Manchu founders of the Qing dynasty (1636–1911), after conquering Beijing in 1644 and Taiwan in 1683, established an even larger empire which continued to expand until the mid 18th century. At its peak, it controlled Manchuria, Outer and Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang, and Taiwan, and exerted influence on its neighbors in Russia, Burma, and Vietnam.

The Western European powers, beginning with the Portuguese and soon followed by the Spanish, Dutch, French, and English, went down the coast of Africa and across the Indian Ocean in pursuit of the spices of the east. In 1492, Columbus headed across the Atlantic Ocean in search of the same oriental luxuries. Once the Spanish took the Philippines and discovered the rich mines of Bolivia in the 1560s and 1570s, silver and gold flowed from Latin America across the Atlantic and Pacific, tying together the markets of the Old and New worlds for the first time. Bullion moved from Latin American colonies to Spain, and from there to Dutch and English financial markets, where European merchants brought the silver to Asia to buy precious commodities. The Manila galleon brought bullion directly across the Pacific from Latin America to Spain’s colonial possessions in Asia. Most of the silver ended up in China, because the great empire’s major exports of tea, porcelain, and silk commanded high prices and the Europeans had no equivalent goods to offer in return. China sent out its high quality commodities and craft goods to meet eager European consumers through the southern coastal ports of Macau, Canton, and Hong Kong. Thus began the continuous interaction of China with Western traders that marks the opening of modern times.

From ancient times, China had always traded with the outside world. Camel caravans crossing the silk routes of Central Eurasia carried textiles, tea, and porcelain to the Middle East and Europe since the first century BCE, and a trickle of adventurous priests and travelers had followed these routes eastward to China. Beginning in the 16th century, however, large numbers of ordinary Western and Chinese people met each other in the great trading cities of South China, doing business across a wide cultural divide. Here the large empires of East and West, with their ships, guns, commercial goods, and officials, had to negotiate acceptable rules to support profitable trade. The leasing of Macau to the Portuguese in 1557 began the system of regulated trade on the coast which evolved into the Canton or “Old China” trade system of the 18th and early 19th centuries. Under this system, the Chinese state restricted the access of Westerners to the interior of China, but allowed them to conduct trade under the name of “tribute,” or gifts to the emperor, which he gratefully returned. This system of commercial exchange lasted from the 18th century until 1842, when China’s loss in the Opium War caused its abandonment. Then a new era of Sino-Western relations—a much less equal one—began.

The British East India Company

For Europeans, the 16th and 17th centuries were the era of exploration, the promotion of Christianity, expansion of maritime trade, and piracy. The Portuguese led the way down the coast of Africa and into the Indian Ocean, supporting their commercial interests with military force. By mounting cannon on their small caravel ships, they were able to muscle their way into a flourishing Asian trade system dominated by Arabs, Indians, Malays, and Chinese.

|

|

|

| |

China has always traded with the outside world. Besides the fabled silk route caravans, Chinese ships competed with Arabs, Indians, and Southeast Asians in maritime trade. The Portuguese were the first Europeans to arrive, looking for a maritime route to China. They negotiated a contract to settle and trade at Macau in 1557.

“Portugese Carracks off a Rocky Coast,” ca. 1540

Circle of Joachim Patinir

National Maritime Museum [cwSP_1540_nmm_BHC0705]

|

|

| |

The Portuguese gained footholds on the Asian mainland at Goa in India and Macau in China by negotiating with the local authorities. Coastal China had suffered from pirate raids led by Chinese smugglers collaborating with Japanese and other armed maritime groups, but Portuguese aid in the suppression of the pirates gained them the reward of a leasehold in Macau. As silver from the New World flowed into China through Macau, Chinese officials found the Portuguese port a profitable source of currency. But they kept the Portuguese confined to the city and did not allow them to penetrate inland.

|

|

|

| |

This detail of Macau in the late 1500s reveals Westerners being carried in palanquins or walking through town accompanied by servants with umbrellas. The inner harbor is busy with Western ships. Macau, the earliest city inhabited by European traders, also attracted Christian converts, including Chinese, mixed-race Chinese, and Japanese.

“Amacao,” ca. 1598

by Theodore de Bry

Hong Kong Museum of Art [cwM_1598_AH8121]

|

|

| |

The Dutch and English followed the Portuguese into Asia using a different political and commercial system. They founded joint stock trading companies, each of which was given monopoly rights to trade in the East Indies. The companies expanded trade for their countries and shareholders, but also used military force to intervene on the mainland. The Dutch founded Batavia (modern Jakarta) in Java as the base for access to the spice islands of Southeast Asia, and they occupied Taiwan and gained access to Japan. The Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie or VOC), founded in 1602, supported the expansion and eventual colonization of Java and the rest of Indonesia.

The first British East India Company, founded in 1600, established footholds by negotiation with local powers on the coast of India. Like the Dutch VOC, it was a national chartered company dedicated to gaining profits from the Asian trade. By the mid 17th century, it had 23 “factories,” or warehouses and living quarters for trading, along the Indian coast, and competed with the Dutch for access to the spice islands at Malacca.

England emerged in the late 17th century from decades of internal warfare just as the Qing empire was completing its conquest of China. In 1684 the Kangxi emperor reopened free trade access to the Chinese coast. A second British company opened in 1698 to seize on the new opportunities, and the two merged to form the united East India Company in 1708. In 1711, it gained its first outpost in Canton. Soon Canton became the central focus of trade with China for both the trading companies and the Qing empire.

|

|

|

| |

The East Indiamen were the largest ships belonging to the British East India Company and some of the largest merchant sailing ships ever built. They also carried guns to protect themselves on the high seas, ensuring British domination of the China trade. This painting shows the ship Asia off of Hong Kong in the 1830s, flying its distinctive flags next to smaller Chinese junks.

“The East Indiaman Asia,” 1836

by William John Huggins

National Maritime Museum [cwSP_1836_nmm_BHC3209]

|

|

| |

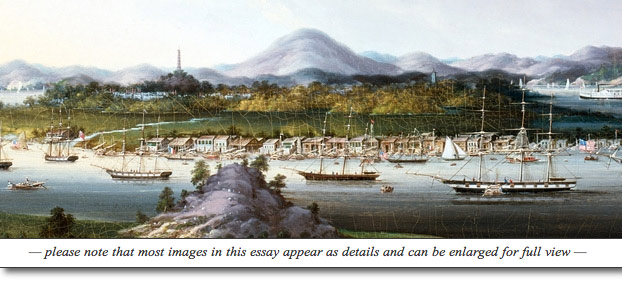

Canton’s natural advantages—its location and its local topography—gave it the preferred position on the China coast for foreign trade. The monsoon winds determined the access of trading ships to the south China coast. From June to September the winds blew from the southwest, allowing sailing ships to ride smoothly downwind across the Indian Ocean, the Arabian Sea, and the South China Sea. When the monsoon ended in October, ships remained in the Canton region for a four-month trading season. The northeast monsoon winds beginning in January gave them smooth sailing back to India and ultimately England. The Pearl River leading from Macau to Canton was easily accessible on the monsoon winds to foreigners. At the same time, since Canton itself was not on the coast, imperial officials could control foreigners who came and went along the river.

|

|

|

| |

A group portrait of three sons of William Money (1738–96), a famous early director of the East India Company. In the picture the eldest son, William Taylor, has his arm on the shoulder of the youngest, Robert, who is pointing to Canton on the map, while the middle son, James, points at Calcutta. The East India Company, which monopolized the British Asian trade for over 200 years, made Calcutta and Canton its key bases. It shipped textiles and opium from India to China in exchange for tea, silk, and porcelain for English consumption. Profits from Asian trade supported the British empire in India and generated great wealth for the prominent landowners who were its directors.

“The Money Brothers,” left to right: Robert (1775–1803),

William (1769–1834), and James (1772–1833)

by John Francis Rigaud

National Maritime Museum [cwPT_1788-92_nmm_BHC2866]

|

|

| |

Ships of the Canton Trade

Traders sailing to China from the West expected great profits but risked great dangers. Typhoons, pirates, and foreign warships could easily destroy a merchant’s career, but those who succeeded made huge profits, as much as 400 to 500 percent on one voyage. Shipbuilders improved the stability and size of the merchant ships in order to enhance the prospects of the China trade. The huge East Indiamen carried the bulk goods on which the trade was based—tea and textiles. The fast clippers, first designed in the United States and copied by others, carried the freshest teas home and smuggled the valuable illegal opium cargoes past Chinese officials. Steamships finally destroyed the Chinese restraints on foreign trade when they arrived in the 1820s, because they could move into shallow waters and help warships bombard Chinese defenses.

|

|

Profits and Perils

Western Ships in the 19th-Century China Trade

|

|

|

Perils at Sea

"The Distress'd Situation of the ship Eliza in a Typhoon in the Gulph of Japan."

An American ship, likely by Spoilum

ca. 1798–1800

Peabody Essex Museum [cwBTW_1798c_ct113] PEM |

|

|

East Indiamen

"East Indiamen in the China Seas,"

by William Huggins

ca. 1820–30

National Maritime Museum [cwSP_1820-30_nmm

_BHC1157.htm] |

|

|

Tea Clippers

"Tea Clipper Medina"

by Philip John Ouless

1817–85

National Maritime Museum [cwSP_1817-

85_nmm

_bhc3486.jpg] |

|

|

Opium Clippers

"The Opium Ships at Lintin Island in China, 1824"

by William Huggins, 1838

National Maritime Museum [nmm_1824_pz0240] |

|

|

Steamships

“The H.E.I. Cos: Steamer Pluto

John Tudor, Lt Commander, R.N.

on her Voyage to China,” 1842

National Maritime Museum [nmm_1842_PAD6713] |

|

|

Warships

“Hon. East India Company's Steamer Nemesis & the Boats of the Sulphur Calliope Larne & Starling Destroying Chinese War Junks in Anson's Bay,” Jan. 7 1841

National Maritime Museum [cwSP_1841_nmm

_PAD5865] |

|

| |

The ships of the East India trade, known as East Indiamen, were the largest merchant sailing ships ever built. They needed both a great deal of space for their cargo and heavy guns to defend against pirates and warships. They increased in capacity from 400 tons in the 18th century to a maximum of 1100 to 1400 tons in the 19th century, and were forty to fifty meters long. In the 1760s, about 20 ships per year visited China, but by the 1840s there were over 300 per year. Despite their size, they faced many dangers. The Royal Captain, 860 tons, 44 meters long, sank off the coast of China in 1773. The Earl of Abergavenny, built in 1797, weighed 1440 tons and was wrecked off the English coast in 1805. Many of these armed merchant ships were built in India and used only for runs from India to China. Those that voyaged from England or the U.S. faced even greater dangers on the high seas. William C. Hunter, a young American, traveled from Salem to China and back three times, and his journey took at least four months each way. Everyone traveling to China risked destruction by typhoons and death by disease or even falling overboard.

|

|

|

Ocean voyages held risks from weather, piracy, privation, illness, and the sea itself, and could go awry at any point, most poignantly off the coast of their home port. Many of the traders were young men in their 20s entering business for the first time. Ocean voyages held risks from weather, piracy, privation, illness, and the sea itself, and could go awry at any point, most poignantly off the coast of their home port. Many of the traders were young men in their 20s entering business for the first time.

“A Man Overboard”

by Thomas & William Daniell, Jan. 1, 1810

National Maritime Museum [cwSP_1810_nmm_PAF4993]

|

Hunter described portrait artist George Chinnery in his 1885 book Bits of Old China: “As a 'story-teller' his words and manner

equalled his skill with the brush, while to one of the ugliest of

faces were added deep-set eyes with heavy brows, beaming with

expression and goodnature.”

“William C. Hunter,”

by George Chinnery

Yale Center for British Art [cwPT_1830s_HunterByChin_ycba]

|

|

| |

Despite these perils, the China trade was so profitable that it attracted daring seamen and ambitious merchants. It also stimulated advances in nautical technology, like the tea and opium clipper ships. Because tea was a seasonal crop, consumers wanted it as fresh as possible. The Americans designed tea clippers in the 1830s to compete with the English. They held less cargo than the East Indiamen and they were built for speed, with narrow pointed hulls and large sail areas. The tea clipper Medina (pictured above in the collage of ships) was active in 1857, at a size of 410 tons. Their peak speed reached 30 kilometers per hour. Even mounted with cannon, on average they sailed at twice the speed of traditional merchant ships. In the Great Tea Race of 1866, two tea clippers raced each other from Canton to London, and both arrived after three months within one hour of each other. The fast clippers also served as excellent opium smuggling ships, as they could outrun the Chinese junks with ease.

The first steamships came to Canton from India in 1828, followed by the East India Company ship Forbes in 1830 and the Jardine in 1835. More than any other technology, steamships brought about the destruction of the Canton trade system. It was not their speed, but their shallow draft, that allowed them to reach Canton without interference from pilots or Chinese officials. The Nemesis (pictured above in the collage of ships), the warship that destroyed the Chinese forts during the Opium War, was a 700-ton ship with only six feet of draft. The highly maneuverable steamships could carry opium to many places, they could tow warships into position, and they could completely escape the controls the Chinese had long exercised over the Canton trade.

In sum, the maintenance of the Canton trade system depended as much on natural geography as on administrative controls. Once the steamships and clippers overcame these natural constraints, the imperial system of controls could not survive.

|

|

| |

|

|

|