| |

UNCIVILIZED BEHAVIOR

There was indeed a civilizing mission in the Philippines, but haunting the undertaking was the uncivilized behavior that accompanied it. Americans initially believed that Filipinos would welcome them peacefully, but as the Philippine independence movement became a war of resistance against the Americans, U.S. tactics became more violent in turn.

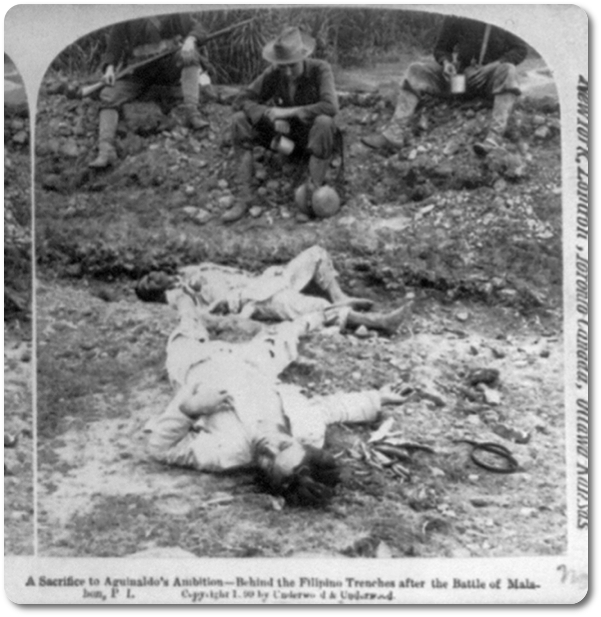

The tension between American ideals and military realities—between the civilizing mission and uncivilized behavior—was not lost on Filipinos fighting for their national sovereignty, on anti-imperialist critics at home, nor even on some of the soldiers themselves. Witting or not, a photographer captured some of that tension in a stereoscopic view taken in 1899 in Malabon, just north of Manila. On an illegible, almost otherworldly landscape lie the bodies of two Filipino soldiers. Their deaths, described in a caption as “a sacrifice to Aguinaldo’s ambition,” suggest the Philippine independence movement was the work of its ambitious and manipulative leader rather than a broadly popular movement. Horizontal mounds of earth divide the photograph in two; above sit three American soldiers, two cut off from our view, and one in a puzzling state of reflection. Not more than a few weeks into this coda to Uncle Sam’s “splendid little war,” some of the young Americans who found themselves in the Philippines may already have begun to question the motives and purposes of the undertaking.

|

|

|

| |

This haunting image from the very early period of the Philippine-American War demonstrates its human costs. A Filipino soldier lies in a trench; the American soldier looking on may convey a sense of unease with the war that had just begun.

Original caption on stereograph: “A Sacrifice to Aguinaldo’s Ambition—Behind the Filipino Trenches after the Battle of Malabon, P.I.,” stereograph, 1899.

Source: Library of Congress [view]

[ph213_1899c_3b04927u]

|

|

| |

Anti-imperialists in the United States—a motley coalition that included starched-collar religious pacifists and blue-collar workers, bleeding-heart Northerners and racist Southerners, self-proclaimed “Friends of the Indian” and die-hard enemies of President William McKinley—sought to get their hands on some of the more gruesome images. They hoped that simple publicity of war’s violence would mobilize opposition to an imperial undertaking that they felt violated America’s core principles. But despite interviewing returned soldiers, activists turned up no reliable images. “I think it would be absolutely impossible to get any pictures from subjects undergoing torture,” reported Arthur Parker, a disillusioned veteran who had become an anti-war activist. “[O]f course no one would ever have a chance to be allowed to photograph the ‘water cure’ operation, or any of the other tortures as being administered.” [1]

Arthur Parker’s reference to the “water cure” pointed to the most controversial instance of violence during the Philippine-American War, and one in which photography played a key role. The water cure was a gruesome interrogation method in which captives were forced to consume approximately five gallons of water, at which point their captors pressed their bloated stomachs until the water came out, and the process began again—ending only with the victim’s confession. The method’s first mention in the U.S. press appeared in a letter by a Nebraska private published in the Omaha World-Herald in May 1900, but few paid much attention until journalist George Kennan, Sr., provided a lengthy and lurid description in the March 9, 1901, issue of The Outlook, a national news weekly. Kennan decried counterinsurgency’s degrading impact on American morality, having observed in the Philippines “a tendency toward greater severity—not to say cruelty—in our dealings with the natives.” The problem, Kennan argued, was not the confusing nature of guerrilla warfare but the fact that

Soldiers of civilized nations, in dealing with an inferior race, do not observe the laws of honorable warfare as they would observe them were they dealing with equals and fighting fellow-Christians. [2]

Such images and criticism prompted a Congressional investigation. In Washington, an ambitious young Ohio judge named William Howard Taft, then head of the commission that governed the islands, acknowledged to the senators “that cruelties have been inflicted [and] that there have been in individual instances of water cure. … I am told—all these things are true.” But if anti-imperialists felt assured that oral testimony and photographs would damn the Army, they were about to learn another lesson. Secretary of War Elihu Root issued a report insisting that “charges in the public press of cruelty” were “unfounded or grossly exaggerated,” and launched a publicity campaign to question the motives of the anti-imperialists by doubting the veracity of their photographs. Root also blamed the press: “yellow journal hypocrites,” he complained, had convinced “millions of good people that we have turned Manila into a veritable hell.”

Photographs of the water cure were not published in the U.S. during the war, making it harder for opponents of the practice to prove that it was happening, and easier for officials to deny. But years later, images of the torture practiced on both sides of the conflict began to surface, and have become iconic images of the war’s brutality.

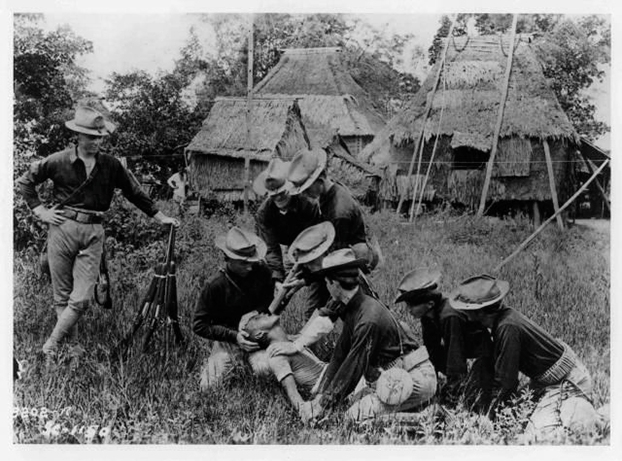

It remains unclear whether an authentic photograph of the water cure has survived—or if one was ever taken. Three images from the historical record give a sense of the practice. In one, soldiers of the 35th U.S. Volunteer Infantry Regiment depict the water cure. As far as we can tell, this is a staged image rather than a record of the actual interrogation of a prisoner. A more historically convincing image—even if less compelling as a photograph—was purportedly taken in Sual in the province of Pangasinan in May, 1901.

Even without photographic evidence, though, images of the water cure circulated widely in American visual culture through illustrations and cartoons, including an artist’s striking rendering on the cover of Life magazine in 1902.

|

|

|

| |

This ca. 1901 photograph of American soldiers administering the “water cure” is likely a staged rather than authentic scene, but has become an iconic image of the war’s atrocities. The “water cure” torture employed by both sides during the Philippine-American War was much discussed, but rarely documented by the camera.

Source: “1899-1902: Fil-American War” [view]

[ph214 _1901]

|

|

| |

This grainy snapshot, reportedly taken in Pangasinan province in May 1901, may be the most authentic evidence of the administration of the water cure. This image did not circulate in the U.S. during the Philippine-American War.

Source: “Philippine-American War, 1899-1902” [view]

[ph215]

|

|

| |

Photographs of the water cure did not circulate in the U.S. during the war, but illustrations did. In this graphic cover of the May 22, 1902 issue of Life (a precursor to the illustrated news magazine that came later), a smiling chorus of European figures observing the “U.S. Army” inflicting the water torture on a Filipino prisoner intones that “Those pious Yankees can’t throw stones at us any more.” The blunt message was that by their atrocious conduct in the Philippines, the Americans, who often criticized European imperialists for their cruel excesses, had shown themselves to be hypocrites.

Life Magazine, #39 (May 22, 1902)

Source: Wikimedia Commons [view]

[ph216_1902_May22]

|

|

| |

The Despoilation of War

Depictions of the water cure were the most extreme—and most hotly debated—aspect of this bloody conflict. But other issues could create controversy as well. At home, President William McKinley explained America’s colonial responsibilities to a visiting delegation of ministers:

To educate the Filipinos, and uplift and civilize and Christianize them, and by God’s grace do the very best we could by them, as our fellow-men for whom Christ also died. [3]

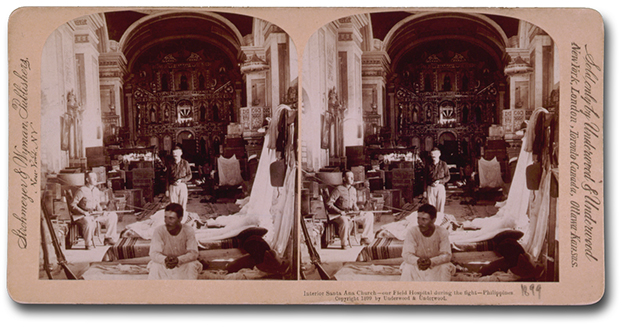

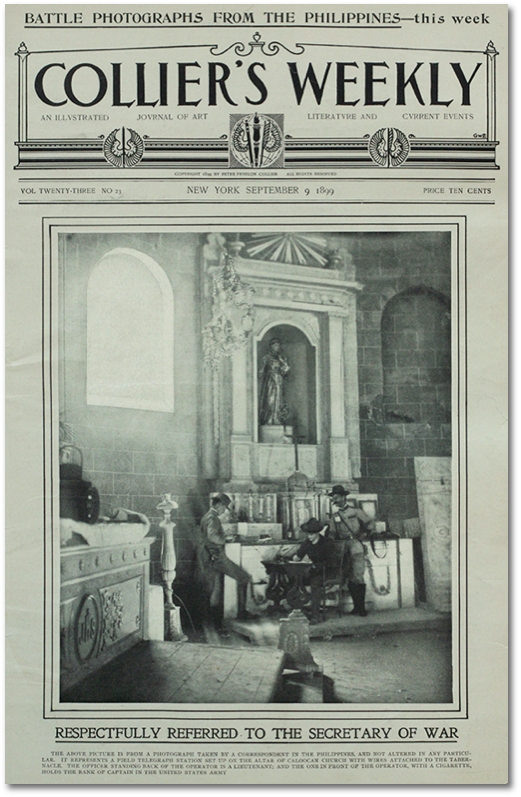

McKinley’s claim that Americans were “Christianizing” the Philippines—a country that was already overwhelmingly Christian—created new conflicts over U.S. colonial policy. So did the actions of ordinary soldiers, who sent home images and objects as souvenirs of their wartime service. Among the items that soldiers sent back to the United States were images of their encampments in town squares and village churches, photographs of the bombed-out shells of old Spanish cathedrals, and even the plundered relics of the colonial clergy. Such were the spoils of war—but in the midst of a controversial conflict, one person’s memento could seem to another viewer to be evidence of desecration. At home in the United States, a violent war that was devastating Catholic sites prompted outcries from leading American Catholics, showing that photographic images could have many meanings.

|

|

|

| |

Both American and Filipino soldiers used churches as forts and hospitals during the Philippine-American War. But at home in the United States, images of destroyed churches and looted altars prompted outcries, particularly from American Catholics.

Original caption on stereograph: “Interior Santa Ana Church—our Field Hospital during the fight, Philippines,” stereograph, ca. 1899.

Source: Library of Congress [view]

[ph088_1899c_LOC_3g04645u]

|

|

|

| |

When this image of American soldiers operating a field station out of a church in the city of Caloocan appeared in Collier’s Weekly in September 1899, it generated a firestorm of protest from religious leaders and a debate in the U.S. about the contradiction between imperial conquest and Christian civilization.

Original caption: “The above is from a photograph taken by a correspondent in the Philippines, and not altered in any particular. It represents a field telegraph station set up on the altar of Caloocan Church with wires attached to the tabernacle. The officer standing back of the operator is a lieutenant, and the one in front of the officer, with a cigarette, holds the rank of Captain in the United States Army.”

Collier’s Weekly 23 (September 9, 1899)

[ph036_1899]

|

|

| |

Postwar Hostilities

While the photographic record carries evidence of the brutal nature of the Philippine-American War, it fails to convey the war’s most striking devastation: the fact that by far most of the Filipino deaths during the conflict were among the civilian population. The U.S. Army recorded 4,200 American soldiers killed. Among Filipinos, between 15,000 and 20,000 soldiers died, but far more civilians—between 100,000 and 300,000—were either killed or sent to early graves by the scorched-earth tactics that starved many out of their homes and destroyed their livelihoods.

All parties to the conflict—the American forces, Aguinaldo’s guerrilla insurgents, and Filipino soldiers attached to the U.S. military—committed atrocities. American troops burned and destroyed villages. Rural inhabitants were forced into concentration camps known as “protected zones,” with surrounding territory designated a free-fire zone. Violence disrupted harvests and killed off livestock. War-related disease, especially cholera, became widespread. Summary executions were routine.

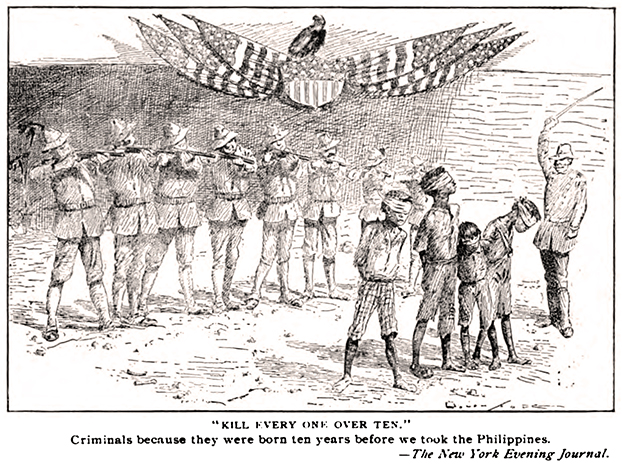

Antiwar critics back in the United States learned of these enormities through letters and reports by a handful of critical journalists, but the censored and self-censored visual record provided them with little evidence. Indeed it was not until May 5, 1902—a mere two months before the U.S. government declared that the insurrection had ended—that the most graphic depiction of the slaughter of civilians appeared in a now-famous cartoon in the New York Evening Journal, a newspaper owned by publisher William Randolph Hearst. Published in the midst of a Senate investigation of alleged U.S. war crimes, the cartoon derived from a notorious order reportedly issued by Brigadier General Jacob H. Smith to kill every male over the age of ten in retaliation for a September 1901 surprise attack that killed some 40 U.S. troops at Balangiga on the island of Samar.

The island, General Smith told a subordinate, was to be destroyed. “I wish you to kill and burn. The more you kill and burn, the better you will please me. … The interior of Samar must be made a howling wilderness.” Faced with the human suffering of civilians, not all American soldiers obeyed Smith’s orders. But twice—once verbally and once in writing—Smith conveyed those words or ones much like them, and in the end, he got the results he sought. [4]

|

|

|

| |

The heading of this 1902 cartoon quotes Brigadier General Jacob H. Smith’s notorious order to kill every male over ten years old in retaliation for a surprise attack on U.S. troops. The caption at the bottom reads “Criminals Because They Were Born Ten Years Before We Took the Philippines.” A vulture, rather than the noble American eagle, perches on the flags and shield above an American firing squad. General Smith was eventually court-martialed for issuing the order. Without photographs to document the violence in Samar, antiwar critics relied on graphic illustrations, but their opponents easily dismissed these drawings as inauthentic and exaggerated.

Originally published in The New York Evening Journal (May 5, 1902), this version appeared in The Literary Digest (May 17, 1902, p. 667).

Source: Google Books [view]

[ph218_1902_May17_Literary_Digest_p667]

|

|

| |

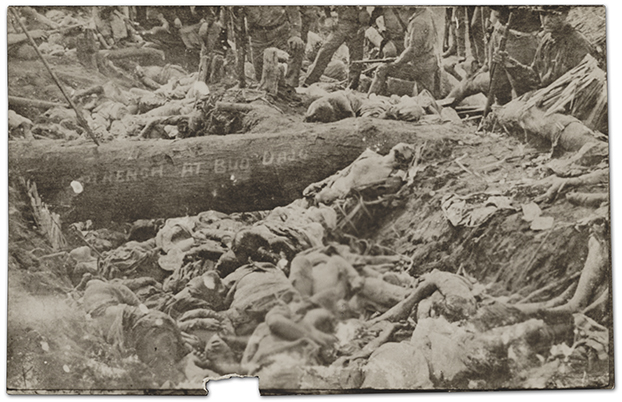

After the formal end of hostilities in 1902, violence continued, and one event that was captured on film generated a final controversy over U.S. military policy in the Philippines. In 1905, the attempt of the U.S. colonial administration to institute a head tax prompted a mass rebellion, and several hundred Muslim Filipinos (known in the Philippines as “Moros”) retreated to an armed camp atop a mountain known as Bud Dajo on Jolo Island.

In a two-day battle in March, 1906 some 400 American soldiers destroyed the camp, killing more than 600 men, women, and children—and prompting, once again, intense debate when news of the event reach the United States. “Brutality has been rewarded, humanity has been punished,” moaned Moorfield Storey, a prominent critic. But Major General Leonard Wood, who led the Bud Dajo attack, earned a commendation, and Rowland Thomas, an American soldier, told readers in Boston that Bud Dajo “was merely a piece of public work such as the army has had to do many times in our own West.” [5] |

|

|

| |

American soldiers observe the corpses of men, women, and children killed in a counterinsurgency operation against Muslim Filipinos in 1906. Commonly known as the Moro Crater Massacre, the Moros, armed mostly with traditional swords and spears, were decimated after withdrawing to an extinct volcano called Bud Dajo.

This photograph—which first appeared in print in Johnstown, Pennsylvania’s Weekly Democrat on January 25, 1907—was described by one critic as “the most hideous Philippine picture published in the United States during the subjugation of the islands.” It was also extremely rare: even though civilian fatalities far outnumbered the deaths of active guerrillas, they were rarely documented on film. It was left to graphic artists and journalists to call these events to public attention.

Source: Library of Congress [view]

[ph217_1906]

|

|

| |

Throughout the controversy surrounding the Moro Massacre, officials repeatedly asserted that muckraking journalists had distorted the facts and were circulating sensational stories to sell newspapers. Photographic evidence, however, made such denials difficult to defend. Military officials who had made the camera into a weapon of war found that it could be wielded against them by antiwar critics. But the war’s opponents—who assumed that visual documentation of atrocities would suffice to mobilize public opinion against the war—learned that images were difficult to control.

In the end, the camera was a powerful weapon, wielded by American officials in the service of colonial conquest, and—whenever they could—by their opponents as well. But colonial officials exercised greater control over when photographs were taken and how they circulated, giving them power to control the story those images told. The visual history of the Philippine-American War, therefore, cannot be recounted solely by looking at the images that remain, but must be told through its absences as well. |

|

| |

|

|

|