| |

A “CIVILIZING MISSION”

For American soldiers—many of whom had never been outside their hometowns before the Philippine-American War drew them thousands of miles across the ocean—photography offered a way to make sense of the new colonial project. It did so in two ways. Photographs depicting the amusing and domestic aspects of military life reassured family members back home—and presumably the soldiers themselves—that tropical conquest had not sapped young American men’s civilizational vigor. And second, photographs allowed Americans to document unfamiliar surroundings and cultural practices. New technologies conveyed that knowledge to audiences at home, turning a strange place into something much more familiar, and selling it to audiences in the United States.

|

|

| |

This group photo of U.S. Army officers depicts a sense of confidence in the American mission in the Philippines. Circa 1899-1901.

Source: Library of Congress

[view]

[ph012_1899-1901_UWisc]

|

|

| |

Through their photographs and descriptions in letters sent home, soldiers depicted themselves as honorable, vigorously manly, and innocently domestic. Many Americans prided themselves on not being an imperial power, but a nation distinct from the empires of the Old World. At the same time, turn-of-the-century doctors warned that extended stays in tropical environments could lead to both physical and moral degradation. Reassuring images of ordinary American masculinity conveyed to viewers at home—who might have received these images in the mail or seen them in magazines—that service in the Philippines had neither weakened Americans nor turned them into European-style imperialists.

|

|

| |

This ca. 1900 studio photo of a baseball team in the Philippines conveyed a reassuring aura of normalcy for those worried about the well-being of American forces in the Philippines.

T. Enami Studio, Manila

Source: Flickr [view]

[ph089_1899c_StuEnami_AmBaseball_flkr]

|

|

| |

The White Man’s Burden

However important Americans may have felt it was to get to know the Philippines, they also felt it important to understand why Americans were there. As often as not, they drew on notions of civilization and uplift that British poet Rudyard Kipling had conveyed in his famous 1899 poem “The White Man’s Burden,” in which Kipling urged Americans to “Take up the White Man’s burden” in the Philippines and “bind your sons to exile / To serve your captives’ need.” [1]

Soldiers posed for the camera with visages serious and calm. Some appeared as visual embodiments of President Theodore Roosevelt’s Kipling-esque call in an 1899 speech urging young American men to undertake “The Strenuous Life.” T.R. explained,Above all, let us shrink from no strife, moral or physical, within or without the nation, for it is only through strife, through hard and dangerous endeavor, that we shall ultimately win the goal of true national greatness. [2]

Americans in the Philippines understood colonial conquest as a burden to be carried by soldiers, missionaries, doctors, and teachers, and they frequently documented their personal sacrifices in images sent back home.

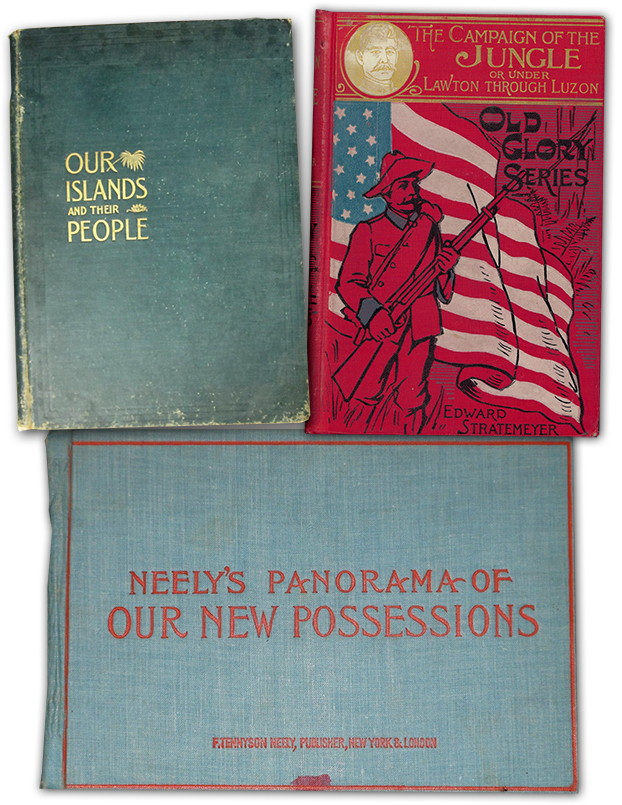

Americans who would never travel to the Philippines as soldiers, teachers, missionaries, or journalists had the opportunity to learn about the place from an explosion of books sold around the country during the Spanish-American War of 1898 and in the years that followed. The books promised an easily digestible introduction to the war’s campaigns, along with maps of the physical and cultural landscapes of America’s new island territories, all lavishly illustrated with photographs that took advantage of their status as honest guides to a far-off reality that most readers would never experience directly. “There is truth-telling that should be prized in photography,” explained the author of one popular guide published as early as 1898 under the title The Story of the Philippines, The El Dorado of the Orient, “and our picture gallery is one of the most remarkable that has been assembled.” Another album titled Our New Possessions, put out that same year by a publisher of mass entertainments, mystery novels, and children’s books, interspersed images of war, destruction, and enemy corpses with landscapes and cozy scenes of camp life—as if to reassure Victorian Americans that their sons and brothers were upholding the standards of civilization.

|

|

|

| |

The voluminous illustrated popular literature supporting the conquest of the Philippines included pocket-sized photo albums, massive encyclopedic tomes, and children’s literature. A sampling includes:.

(1) Our Islands and Their People as Seen with Camera and Pencil (N. C. Thompson, 1899), William S. Bryan, ed.

(2) Neely’s Panorama of Our New Island Possessions

(F. Tennyson Neely Publishers, 1898) [view full album online]

(3) The Campaign of the Jungle: Or, Under Lawton through Luzon, by Edward Stratemeyer

(Lee and Shepard, 1900), a volume in a children’s series titled Old Glory Series.

[ph035_1899_Our_Island] [ph053_1899_neely_AmNewPoss] [ph108_1900_stratemeyer]

|

|

| |

Stereographic Visions

At the turn of the century, stereographs offered a seemingly authentic experience of war and colonialism. By peering at a double photographic image through a special lens, viewers would see an optical illusion of three-dimensional depth that gave a you-are-there experience. The stereograph was the first visual mass medium, and—along with postcards—were the most widely circulated images of the Philippines. By 1900, half of American households had a stereoviewer and they purchased nearly 10 million stereoview cards every year through mail-order catalogues or from traveling salesmen. Consumers were so eager to obtain images of America’s new colony that stereoview companies sent photographers to the Philippines to collect images. Their stereographs of the Philippines blended education and entertainment as they told stories of American benevolence in their new colony.

|

|

|

| |

Original caption on stereograph: “A welcome to Uncle Sam’s protection—three Filipinos entering American lines, Pasay, P.I.,” stereograph, ca. 1899.

Source: Library of Congress [view]

[ph022_1899_LOC3b36587u]

|

|

| |

Original caption on stereograph: “Filipino Women Seeking Help from American Soldiers,” stereograph, ca. 1899.

Source: Library of Congress [view]

[ph085_1899c_LOC3c13594u]

|

|

| |

Original caption on stereograph: “Manila, Philippine Islands: Maimed Filipinos—Healing the Wounds Our Bullets Inflicted—U.S. Hospital,” stereograph, ca. 1899.

Source: Library of Congress [view]

[ph052_1899_kilburn024]

|

|

| |

Original caption on stereograph: “Old woman shot through the leg while carrying ammunition to the insurgents. In hospital, Manila,” stereograph, 1899. (detail)

Source: Library of Congress [view]

& University of Wisconsin

[ph040_1899_UWisc]

|

|

| |

Original caption on stereograph: “The right way to Filipino Freedom—Boys in Normal High School, Manila, Philippine Islands.” stereograph, 1900.

Source: Library of Congress [view]

[ph102_1900_UWisc]

|

|

| |

Original caption on stereograph: “Our young Filipinos in holiday attire at the Fourth of July celebration, Manila, P.I.,” stereograph, ca. 1900.

Source: Library of Congress [view]

[ph096_1900_LOC_3b27481u]

|

|

| |

Selling Civilization

The U.S. public was bitterly divided over the American conquest of the

Philippines. While “anti-imperialist” critics denounced the invasion, supporters of the war defended it in terms of America’s destiny to spread civilization and progress to backward peoples and nations. In the rhetoric of the pro-war camp, the independence movement led by Emilio Aguinaldo, which began against Spain and was redirected against the American invaders after Spain’s defeat, was commonly referred to as an “insurrection.”

Even more vividly than in photographs, poems, and prose, the mystique of the white man’s burden found expression in a flood of colorful cartoons depicting the global spread of the Western world’s superior material as well as spiritual civilization. As seen in the two samples below, the military invasion was depicted as paving the way for an invasion of secular as well as religious white missionaries—and acquisition of the Philippines was depicted as a stepping-stone through which U.S. manufactured products would eventually make their way into the vast potential markets of China. |

|

|

| |

This graphic by S.D. Erhart, published in 1900 in the popular magazine Puck, depicts American colonialism as a benevolent form of uplift. As U.S. soldiers depart, Uncle Sam introduces a group of female teachers to the Filipinos, depicted in typical caricatures—here as childlike and half-naked—that suggested they were in need of education and civilization. The U.S. government did send small numbers of teachers to the Philippines soon after acquiring the colony, but in reality, American troops outnumbered teachers throughout the military occupation.

Caption on print: “If they’ll only be good. ‘You have seen what my sons can do in war—now see what my daughters can do in peace.’” Puck 46 (January 31, 1900)

Source: Library of Congress [view]

[ph211_puck_1900_739_yale]

|

|

|

| |

Supporters of U.S. policy in the Philippines frequently reminded the American public that acquisition of a colony in Asia could open the door toward trade opportunities in China. This 1900 cartoon by Emil Flohri shows Uncle Sam bringing not only “education” and “religion” but a vast array of consumer goods to an eager Chinese population. The many signs on the Chinese shore itemize all the goods that presumably will find a market in China. The tiny Chinese figure dressed in traditional clothing follows the condescending stereotype demeaning non-Western, non-Caucasian peoples.

Caption on print: “And, after all, the Philippines are only the stepping-stone to China.” Judge (ca. 1900).

Source: Wikimedia Commons

[view]

[ph100_1900_Mar21_Judge]

|

|

|