| |

HOSTILITIES

The ensuing hostilities lasted for about three years; went through several fairly distinct military phases; introduced “gunboat diplomacy” to Asia in raw and undiluted form; and ended in August 1842 with the first of the “unequal treaties” that England and the other Western powers expanded on and maintained vis-à-vis China until World War II, almost exactly a century later.

In viewing the contemporary “battle art” that follows here, it may be helpful to keep several things in mind. The graphics are heavily weighted toward the British side, simply because that is where the weight of the record lies. A fairly substantial body of writing about the war did emerge on the Chinese side, along with a very insubstantial number of random illustrations. (These writings quickly made their way to Japan, where they inspired publications that included lively original illustrations inspired by the textual Chinese accounts.) By and large, the Qing court had little reason to publicize its struggle and defeat, and local officials preferred to play down the foreign attacks. The vast majority of Chinese felt little immediate impact from the war. Only the Cantonese population roused its militia to fight the British, but this action was fleeting and received little recognition in the rest of the empire. China was not yet a nation, in which local actions had broad impact across its huge territory, but a dispersed empire without a unified consciousness of the foreign threat. There were as yet, moreover, no networks or mechanisms of popular mass communications.

The British graphics themselves, moreover, have many limitations. In these years before photography or the telegraph, communication in general was slow and cumbersome. Sketches and paintings done on the scene by Western observers reached audiences back home in the form of engravings or lithographs long after the events portrayed had taken place. The original artist on the one hand, and final artist, engraver, and printer on the other hand, were often continents apart, and months or even several years apart as well. “Timely reportage,” including visual representation, lay decades in the future.

The Western graphics also, perhaps unconsciously, were skewed and self-censored. Usually, artists did not dwell on the war dead; and where they did do this for their own side, they looked to battlefield deaths rather than the far more common cause of British casualties and fatalities: disease. Fever, ague, malaria, dysentery, diarrhea, gangrene, sunstroke, even malnutrition all ravaged the foreign troops. Thus, for the period between July 13 and December 31, 1840, when non-combat illness and death were especially severe, official hospitalization figures recorded 5,329 admissions and 448 deaths. An English military account published in 1842 similarly observed, almost in passing, that “at one time as many as 1,100 men were in hospital; and in the 37th Madras regt. out of 560 men, only 50 were fit for duty. Many men and officers were obliged to be invalided.”

As in all imperialist conflicts in this age of disproportionate military power, moreover, casualties on the Chinese side were vastly greater than those suffered by the British forces. More than a few battles amounted to massacres. A report submitted to the British government in 1847 put total United Kingdom combat casualties in the first Opium War at 69 killed and 451 wounded, for example, while estimating Chinese casualties including deaths at 18,000 to 20,000. While the popular Western war illustrations convey disparity of power, they only hint at the grim calculus of death that came with this.

The war graphics alone also tend to submerge the complexity of racial, ethnic, and social distinctions. A large percentage of the forces the British relied on, for example, was comprised of sepoys, or Muslim and Hindu recruits from India—identified in reports of the time by such phrases as “Bengal volunteers” and “Madras native infantry.” The British force also had substantial contingents of Irish and Scottish troops.

Although England established and controlled its worldwide empire everywhere by relying on subject peoples, the visual record does not draw attention to the polyglot nature of “British forces” in China. In a different direction where ethnicity is concerned, there are no graphic records at all which might confirm (or repudiate) the impression held at the time that Chinese often treated Indian prisoners more harshly than their white captives, although the latter were severely abused as well.

There is a contrary dimension to this also, however. While English writings of the time sometimes speak disdainfully of the Chinese, the ostensible “British” and “Chinese” antagonists interacted in complex ways beyond plain adversity. It is obvious that the drug trade thrived because of complicity by Chinese at every level of society, from officials to smugglers and secret societies to users. It was common practice, moreover, for the foreign forces to recruit and pay wages to local “coolie” labor as their military campaigns up and down the coast unfolded.

Additionally, both sides engaged in abuse of prisoners, wanton plunder, and other barbarous behavior. In some of the cities and towns bombarded by the British, particularly where most inhabitants fled the scene, mayhem involved both sides: Chinese mobs moved in, and competed for loot with the foreigners. On at least one occasion, the looters on each side even acted in concert. The war illustrations give only a hint of this. On other side of the coin, men of moral integrity on the Chinese side who spoke strongly but in vain against the opium trade had counterparts among politicians in London and a small number of the merchants and ship captains engaged in the China trade.

Mostly, in any case, the Western artists and illustrators—whether on the scene or imagining events back home—focused their attention on warships, naval and ground-force dispositions, and background landscapes. They often seemed inordinately attracted to sails and puffs of smoke. Yet the technology of the war, the martial nationalism of this imperialist exercise, the omissions themselves are illuminating. And occasionally—like Walter Sherwill and the “Opium Factory at Patna”—on-the-scene artists like John Ouchterlony of the Madras Engineers can still take us by surprise.

Phase I of Hostilities: November 1839–January 1841

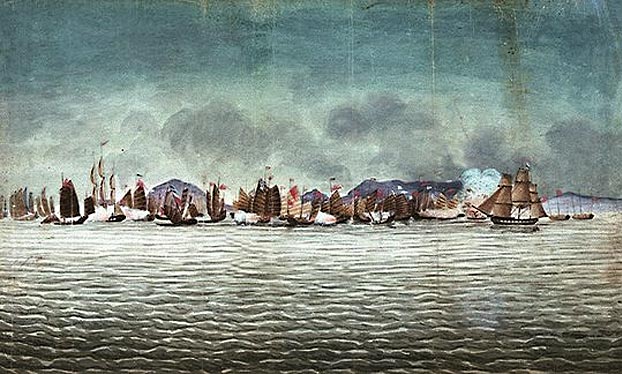

On November 3, 1839—still with no declaration of war having emanated from either side—the unresolved Kowloon incident coupled with other complications precipitated a dramatic military confrontation at Chuanbi on Canton Bay.

On this occasion, two British frigates—the 28-gun Volage and 18-gun Hyacinth—took on 29 Chinese vessels that were blockading the harbor (16 war junks and 13 “fire-boats,” craft packed with straw and brushwood, sometimes covering chests of gunpowder, that were set ablaze and floated toward the wooden ships of the enemy). One junk was blown to bits by a lucky shot to its magazine, several other junks were sunk or heavily damaged, and only one British sailor was wounded as opposed to at least 15 Chinese killed. Despite this humiliation, Commissioner Lin’s report to the throne gave no hint of defeat and the emperor was persuaded that the Chinese had won a great victory.

|

|

|

| |

HMS Volage & HMS Hyacinth confront Chinese

war junks at Chuenpee, November 3, 1839, by Miller

National Maritime Museum

[1839_ChWar_PAF4873_nmm]

|

|

| |

“The First Battle of Chuanbi, November 1839”

by Captain Peter William Hamilton

Wikimedia Commons

[1839_chuenpee_hamilton_wm]

|

|

| |

In these volatile circumstances, Captain Elliot requested that reinforcements be dispatched to Canton; debate on the vice of opium versus the virtue of free trade reached a crescendo in Parliament; and Foreign Secretary Palmerston cast aside his pragmatic reservations. A formal declaration of war against China was issued on January 31, 1840—not by London, but by British authorities in India acting on behalf of the home government. In the months that followed, a large British fleet was assembled for dispatch to China.

Despite his misleading report to the throne about the battle of Chuanbi, Commissioner Lin—who simultaneously served as commander in chief of the imperial navy at Canton—was aware that the Chinese were too weak to challenge the foreign forces directly. On the one hand, he continued to attempt to suppress the opium traffic by admonishing and punishing dealers and users on the Chinese side. On the other hand—and here Lin badly misread the anger, determination, profit-seeking, and national pride of the foreigners—he still hoped moralistic arguments might persuade England to abandon the trade.

Early in 1839 Lin had drafted a letter to Queen Victoria but apparently never attempted to send it. During these heightened end-of-the-year tensions, he wrote a second letter to the queen and actually dispatched it, to no avail. It never reached her hands.

In the midst of all this, the six seamen accused of murder in Kowloon were returned to England where, unsurprisingly, they all went unpunished.

|

|

| |

Commissioner Lin’s Letter to Queen Victoria

|

|

| |

Commissioner Lin entrusted the second of his letters to Queen Victoria to the captain of the East Indiaman Thomas Coutts, who in October 1839 had defied British authorities by running the British blockade at Canton and signing a bond with Lin agreeing he would not transport opium. The owners of the Thomas Coutts were Quakers opposed to the drug trade. Upon reaching London in January, the captain turned the letter over to one of the co-owners, who in turn attempted to deliver it to Foreign Secretary Palmerston. When the foreign office refused to accept the letter, it was made available to the Canton-based missionary publication Chinese Repository, which printed it in February 1840.

|

|

|

The Indiaman Thomas Coutts carried Commissioner Lin’s 1839 letter to London. The Indiaman Thomas Coutts carried Commissioner Lin’s 1839 letter to London.

Painting by

James Miller Huggins.

Wikimedia Commons

[1836_ThCoutts_Huggins_wm] |

The Chinese original of Lin’s letter to The Chinese original of Lin’s letter to

Queen Victoria (detail)

Wikimedia Commons

[1839_Lin_LetterQuV_wm]

|

After the British government refused to accept Lin’s letter, a translation appeared almost immediately in the Protestant missionary publication Chinese Repository. After the British government refused to accept Lin’s letter, a translation appeared almost immediately in the Protestant missionary publication Chinese Repository. |

| |

The forces dispatched to Canton in response to Captain Elliot’s entreaties arrived in June 1840 under the command of his cousin, Rear Admiral Sir George Elliot. The fleet consisted of 48 ships—16 warships mounting 540 guns, four armed steamers, 27 transports, and a troop ship—and carried fuel for both the steamers and the troops in the form of six million pounds of coal (3,000 tons) and 16,000 gallons of rum. The fighting force numbered some 4,000 men.

As the war dragged on, these forces were increased. The first steam- and sail-powered iron warship ever built, for example, owned by the East India Company and famously named the Nemesis, arrived in Macao in November 1840 after a perilous voyage from England. Later reinforcements brought more iron steamers as well as sail-powered warships, and increased the total number of ground forces and seamen to around 12,000.

After the fleet’s arrival, the British moved quickly to assert their authority and demand (among other things) compensation for the seized opium, abolition of the restrictive Canton trade system, and the right to occupy one or more islands off the coast. Admiral Elliot avoided confronting the Chinese forces Lin had assembled at Canton. Instead, he imposed his own naval blockade there and proceeded to move north along the coastline with a portion of his forces, accompanied by Charles Elliot, England’s chief diplomat on the scene.

One objective of this push north was to find responsible officials at a major port who would agree to deliver the British government’s ultimatum to the emperor in Peking (Beijing). A second, related objective was to pressure the Qing court into agreeing to negotiations by threatening to cut off north China from the resource-rich and economically critical south.

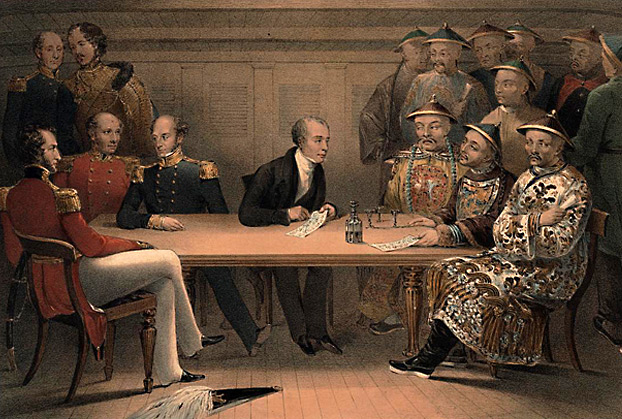

By early July—after blockading Amoy (Xiamen), where local officials refused to allow a landing party—the fleet was approaching the Yangtze River delta, some 700 miles north of Canton. On July 4, officers from the warship Wellesley, along with the interpreter Karl Gützlaff, met with local officials from strategically located Chusan (Zhoushan) Island in a vain attempt to persuade them to surrender peacefully. (The officials asked them, among other things, why they were being threatened because of disputes centering on Canton.)

|

|

|

| |

Conference between British and Chinese officials on board the Wellesley off Chusan, July 4, 1840. The missionary and interpreter Karl Güzlaff is seated in the center. The British bombarded and occupied the capital of Chusan the following day, after failing to persuade these local officials to surrender peacefully.

From a drawing by Harry Darell

Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library

[1842_conf_darrell_brown]

|

|

| |

“Taking the Island of Chusan by the British, July 5th 1840”

The British landing party sets out for shore under the cover of gunfire from the fleet.

From a drawing by Harry Darell

National Maritime Museum

[1840_PAG9185_Chusan_nmm]

|

|

| |

“Chusan Bay” 1840

This depiction of the July 5, 1840 landing at Tinghai captures the distinctive eye and style of Lt. John Ouchterlony of the Madras Engineers, whose narrative, including 53 woodcuts based on his on-the-scene drawings, was published in an 1844 book titled The Chinese War: An Account of All the Operations of the British Forces from the Commencement to the Treaty of Nanking.

[ou_068a_ChusanBay]

|

|

| |

After occupying Chusan, the fleet blockaded Ningpo (Ningbo), a major port close by, after officials there refused to accept a letter setting forth the British demands. The force then headed north toward Tientsin (Tianjin) and the Pei-ho (Hai He), the strategic waterway leading to Peking.

While the expedition was advancing toward Tientsin, the British also engaged in a

brief show of force in the south, known as the Battle of the Barrier. The barrier in question ran across the isthmus separating Portuguese-controlled Macao from the rest of the mainland. Commissioner Lin had mobilized forces that threatened to drive the British from Macao. In a preemptive assault that began and ended in a single day (August 19), British warships silenced the Chinese battery at the barrier; fired on the ineffective war junks anchored offshore; landed a brigade of some 380 men (of whom almost half were Bengal volunteers); destroyed the Chinese military stores; and then withdrew.

Even in this brief confrontation, the disparity in casualties was typical—and so was the manner in which Chinese officials minimized their losses. Casualties on the British side amounted to four wounded and no one killed. The Chinese, on their part, put their losses at seven or eight men killed—a figure English observers on the scene believed should be “multiplied by 10.” Like the Battle of Chuanbi less than two months earlier, however, Lin’s reports presented this encounter, too, as a Chinese victory.

|

|

|

| |

“Barrier Wall, Macao”

The barrier on the land bridge separating Macao from China is viewed here from a British encampment in Macao, with British warships to the left and Chinese war junks close to the barrier on the right.

From John Ouchterlony, The Chinese War (1844), p. 81

[ou_080a_Macao]

|

|

| |

At this point, Lin’s days as imperial commissioner were numbered. Near the end of August, the fleet carrying the two Elliots reached the approach to Peking and succeeded in conveying the British demands to local officials at Tientsin. Finally awakened to the real nature of the foreign threat, the emperor responded with fury and Lin became transformed from hero to scapegoat. On August 21, the emperor chastised him harshly: “Externally you wanted to stop the [opium] trade, but it has not been stopped; internally you wanted to wipe out the outlaws [opium smugglers and smokers], but they are not cleared away. You are just making excuses with empty words. Nothing has been accomplished but many troubles have been created. Thinking of these things, I cannot contain my rage.” Lin was stripped of his title of imperial commissioner in September, but allowed to remain in Canton that fall and winter to offer assistance to his successor.

Qishan, Lin’s successor as the mandarin appointed to deal with the British, rose and fell even more quickly in emperor’s eyes. Lin warned the emperor that negotiating with the foreign barbarians would never work: “the more they get the more they demand, and if we do not overcome them by force of arms there will be no end to our troubles.” Qishan, however, took a softer line, hoping to persuade the foreigners to withdraw simply by threatening to cut off their trading privileges and then making some concessions. He persuaded the two Elliots to return to Canton by intimating that the Chinese were prepared to engage in serious negotiations there.

By November, the British had withdrawn to Macao. The promised negotiations began in Canton in late December, with Charles Elliot as chief negotiator on the British side. Palmerston’s instructions to Elliot now included these minimal conditions for an agreement: the opening of the five ports of Canton, Amoy, Foochow (Fuzhou), Ningbo, and Shanghai; cession of an island; and indemnities for both the value of the confiscated opium and costs of the military expedition. Qishan offered only a smaller indemnity than requested, and even this was done without the Qing court’s knowledge.

By January 1841, the British had become aware that Qishan was not prepared to make substantial concessions. The fleet had been reinforced during this lull, and the next great show of British force was unleashed at a familiar place of battle: Chuanbi, which along with a sister fort at Tycocktow guarded the strategic Bocca Tigris strait, leading to Canton itself.

The famous “Second Battle of Chuanbi” took place on January 7, lasted but an hour, and ended with both forts captured, an estimated 500 or more Chinese killed, and perhaps half that number wounded. British casualties were 38 wounded.

|

|

|

| |

“Attack and Capture of Chuenpee, near Canton”

1843 engraving based on artwork by Thomas Allom

Between 1843 and 1847, Thomas Allom published close to 150 illustrations of “China,” including but by no means limited to battle scenes of the Opium War. Allom never visited China, and some of his prints acknowledge being based on drawings or sketches by others. (Here, for example, the print includes a line indicating it is based on a sketch by “Lieutenant White, Royal Marines.”) These illustrations are thus “imagined” scenes—and usually, even in the war renderings, highly romanticized. Allom’s considerable audience in England thus received a doubly deceptive impression. The war was by and large sanitized and beautified, while China itself—especially in scenes having nothing to do with the Opium War—was rendered exotic and even alluring in many ways.

Beinecke Library, Yale University

[Allom_1839_Chuenpee_Yale]

|

|

|

| |

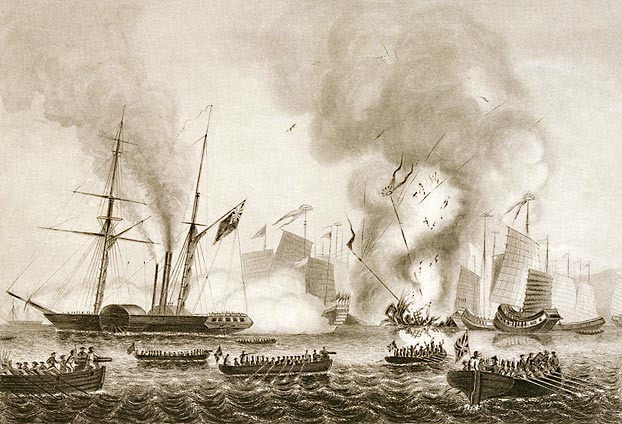

“NEMESIS Destroying the Chinese War Junks in Anson’s Bay, Jan 7th 1841”

This famous print of the Second Battle of Chuanbi by E. Duncan,

dated May 30, 1843, records the first battle appearance

of the revolutionary iron steamer Nemesis.

National Maritime Museum

[1841_0792_nemesis_jm_nmm]

|

|

| |

“Attack on the Chinese Junks” 1841

[1841_AttkJunks_Bridgeman]

|

|

| |

“Attack on the War Junks at Chuenpee Creek”

Frontispiece to volume ll of a book by Captain Sir Edward Belcher, published in 1843 with the imposing title Narrative of a Voyage Round the World: Performed in Her Majesty’s Ship Sulphur, During the Years 1836-1842, Including Details of the Naval Operations in China, from Dec. 1840, to Nov. 1841.

[1843_belcher_000_Chuenpee]

|

|

| |

The Iron Warship Nemesis Makes Its Debut

|

|

|

| |

“The Hon. East India Companys Steamer “Nemesis” and the boats of the Sulphur, Calliope, Larne, and Starling destroying the Chinese War Junks in

Ansons Bay. January 7, 1841”

National Maritime Museum

[1841_Chuenpee_PU5865_nmm]

Gunboat diplomacy attained a new level technologically in the Second Battle of Chuanbi, when the 660-ton iron steamer Nemesis entered the fray. Constructed in Liverpool for the East India Company, the Nemesis was distinctive in several ways. Driven by two paddle wheels, the warship was made almost completely of iron. It was flat bottomed, with an unusually shallow draught of only six feet when fully loaded—making it particularly suitable for navigating China’s shallow waters. And although its three highest officers were from the Royal Navy, the crew and the rest of the officers were civilians.

On January 7, seeing action for the first time ever, the Nemesis landed a force of some 600 sepoys at Chuanbi; participated in the bombardment of the fortifications; and made a particularly dramatic impression by blowing up a war junk with a Congreve rocket. An 1845 book about the Nemesis recorded that “The smoke, and flame, and thunder of the explosion, with the broken fragments falling round, and even portions of dissevered bodies scattering as they fell, were enough to strike with awe, if not fear, the stoutest heart that looked upon it.”

This was the scene that artists predictably recorded and publishers promoted back home—albeit, as always, some time after the event. The Illustrated London News published an engraving of the spectacular moment at Chuanbi in November 1842. The popular colored print by E. Duncan reproduced above this box appeared in 1843, while the dramatic rendering at the top of the box appears to have been issued as late as 1851.

|

|

|

| |

“The Nemesis Steamer Destroying Chinese War Junks, in Canton River,

from a sketch in the possession of the Hon. East India Company”

Illustrated London News, November 12, 1842

[iln_1842_pg420_nemesis_wid]

|

|

| |

Like all other steamer warships, the Nemesis also raised sail in certain circumstances. This graphic appears in the 1844 book Narrative of the Voyages and Service of “The Nemesis,” co-authored by the ship’s commander William Hutcheson Hall.

[1847_Nemesis_Hall3rdEd_gb]

|

|

| |

The Nemesis continued to play a conspicuous and versatile role in subsequent battles, and by war’s end had been joined by a number of other iron steamers, all but one of them operated by the East India Company. In addition to firing heavy shells and rockets, along with ferrying troops, the shallow draught of the steamers enabled them to close in and grapple with Chinese war junks, while their ability to defy winds and tides made them useful for towing the big British men-of-war within firing range of coastal fortifications that were under attack.

The British Library possesses an unusual Chinese scroll with a rough sketch of the Nemesis and another British warship, accompanied by a 55-line poem. There is a penned-in English translation on the scroll as well, apparently dating from around the time of the Opium War.

|

|

|

| |

Chinese scroll with illustration of the iron steamer Nemesis and a British man-of-war, along with a 55-line Chinese poem. (detail)

[1840c_ChScrollNemesis_D40019-04_left]

The British Library categorizes the verse on the scroll as “doggerel.” Insofar as accuracy goes, it amounts to a poetic counterpart to the reports of imaginary victories Commissioner Lin and other Chinese officials produced in the early stage of hostilities. In vivid, almost epic language, the poem describes how the gods intervened to drive the English warships aground in a storm, after which “the foreign devils in hundreds then were put to death,” while others “fell sick by fierce disease” and perished.

The closing lines are devoted to the “fire ship” encased in iron with a wheel on each side “which is moved by the use of burning coal and turns around like a galloping horse.” The poet acknowledges that “Its shape and fashion astonish mankind”; but, like all the other enemy ships, the gods drove it onto the rocks.

|

|

| |

On January 20, confronted by the British show of force at Canton, Qishan acknowledged his helplessness and indicated that, among other things, China was willing to cede Hong Kong, pay an indemnity of six million dollars, engage in official relations on an equal footing, and reopen Canton to trade. When this so-called Convention of Chuanbi was submitted for approval, the Daoguang emperor again flew into a rage. Qishan was imprisoned and sentenced to death; his family property was confiscated; and in May 1842, after his sentence was commuted, he was banished to a remote area near the Amur River far in the north.

As it transpired, Charles Elliot, Qishan’s counterpart in the agreement, also received a stinging reprimand from his government. On April 21, Palmerston castigated him for having settled for the “lowest” possible terms, and stripped him of his appointment. Among other things, Palmerston was critical of Elliot’s failure to insist on compensation for the opium Lin had destroyed, as well as his agreement to withdraw British forces from strategically situated Chusan and his acceptance of less than absolute rights to Hong Kong (which Palmerston spoke of disparagingly as “a barren island with hardly a house upon it”). Given the excruciating slowness of communication, Elliot did not learn of his disgrace until late July, when his dismissal notice arrived—followed shortly by his successor, Sir Henry Pottinger.

|

|

|

| |

“Encampment at Toong-koo, Where Captain Elliot Met Keeshe”

John Ouchterlony’s depiction conveys the rough setting in which Elliot and Qishan worked out the Convention of Chuanbi, which both the Chinese and British governments refused to recognize.

From The Chinese War (1844), p. 65

[ou_064a_Camp]

|

|

| |

Phase II of Hostilities: February 1841–June 1841

Before the news of his dismissal and replacement arrived, Captain Elliot,

convinced that the emperor would not carry out the terms he and Qishan had agreed upon at Chuanbi, initiated a series of attacks that directly threatened Canton. In the last week of February and first week of March—in a succession of quick battles sometimes known as the Battle of the Bogue (also Battle of Bocca Tigris), Battle of the First Bar, and Battle of Whampoa—British warships including the Nemesis gained control over the Pearl River and placed themselves in position to besiege Canton.

Estimated casualties conformed to the familiar pattern: a single British soldier was killed when his gun misfired, while fatalities on the Chinese side probably numbered around 500, including an admiral whom one of the British warships honored with a cannon-salute when his body was taken away by his family.

|

|

|

| |

This Chinese sketch of defensive preparations at Anunghoy in the strategic Bocca Tigris straits leading to Canton was found by the British after they destroyed these fortifications on February 26, 1841. The Chinese had stretched iron cables, resting on junks, across the narrow channel in a vain attempt to deter the British warships.

Wikimedia Commons

[1841_Feb26_BoccaT_1850c_wm]

|

|

| |

“Attack on First Bar Battery, Canton River”

This rendering of a battle that took place just below Whampoa on February 27, 1841, appeared in Narrative of a Voyage Round the World by Edward Belcher, published in 1843 [vol. 2, p. 154]

[1843_belcher_154a_1stBarBat]

|

|

| |

Control over Whampoa enabled the British to bring up a large force for an attack on Canton, which they proceeded to carry out the following May. On May 21, at Elliot’s urging, British subjects still in Canton left the city—following which Chinese soldiers and mobs plundered and gutted the “factories” where they conducted business. By May 24, the British force had taken the forts protecting the city and commenced bombarding Canton itself. Local officials together with wealthy hong merchants responded quickly by offering Elliot a “ransom” of six million dollars to desist—leading to a truce agreed to on May 27.

|

|

|

|

| |

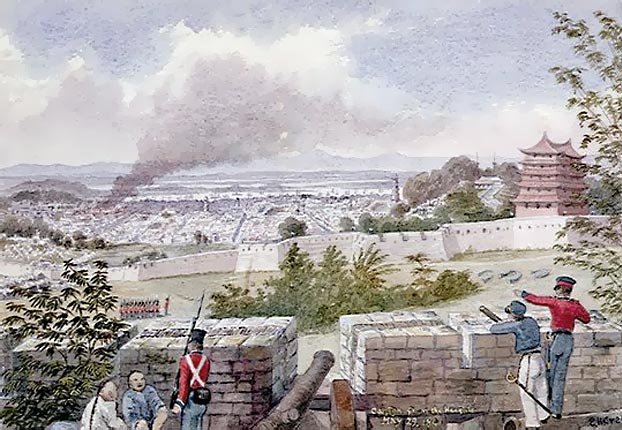

Dr. Edward H. Cree, a surgeon with the Royal Navy who participated in the first Opium War, maintained a personal journal illustrated with his own watercolor paintings. These impressions of the Battle of Canton depict British sailors towing the big warships toward the besieged city on May 24, 1841 (above, top), and ground forces bombarding Canton from the surrounding heights (above).

National Maritime Museum

[cree_081_HurrahCanton] [1841_6028_Canton_nmm]

|

|

| |

The truce at Canton set the stage for one of the most celebrated moments in later Chinese recollections of the war. On May 29, as Chinese troops began to withdraw from the city and British forces prepared to do likewise, local gentry in surrounding villages mobilized militia to attack the invaders. They had only primitive arms like hoes, spears, and a few matchlock guns, but were furious at the foreigners’ destruction of local tombs; rape of local women; and looting of food, clothing, and valuables. In short time, the gentry gathered a civilian force that peaked at around 10,000 men from some 100 villages.

On May 30, in the midst of a torrential rainstorm near the village of Sanyuanli, this militia encountered and surrounded a detachment of Indian sepoys led by English officers. The downpour left the foreigners mired in paddy-field mud, and caused their flintlock muskets to misfire. One of the sepoys was killed and 15 wounded before British reinforcements arrived.

|

|

|

| |

John Ouchterlony’s rendering of the battle in the rain at Sanyuanli

was reduced to a small graphic in his 1844 book, as opposed to the usual full-page illustration. By contrast, this episode dominates many Chinese recollections of the first Opium War.

From The Chinese War (1844), p. 156

Beinecke Library, Yale University

[ou_156_rescue]

|

|

| |

Fearing an attack by the main British army, senior officials associated with the Manchu court’s regular military forces quickly dispersed the militia and negotiated another truce. To Elliot and British officers on the scene, the encounter at Sanyuanli was insignificant, and it received but passing notice in official military reports. On the Chinese side, by contrast, rumors soon placed the British dead at “80 or 90,” with many others wounded, and claimed that the foreign barbarians would have been completely annihilated if only the local Manchu general had sent reinforcements. Sanyuanli became turned into a great grass-roots victory by the Chinese people, and local literati, villagers, and examination students castigated the corrupt imperial army and court-appointed officials for paying off the foreigners to save their city.

In present-day Chinese accounts of the Opium War, Sanyuanli still stands out as the major victory of the war, a symbol of the potential power of the unified Chinese masses. As the Chinese historian Bai Shou-yi has written, “This was the earliest known spontaneous struggle by the Chinese people against foreign aggression in modern history.” Modern Chinese films of the war often stress the Sanyuanli victory instead of the humiliating defeats.

|

|

|

| |

Phase III of Hostilities: August 1841-March 1842

Captain Elliot’s willingness to withdraw from the siege of Canton reflected his conviction that England would not attain its objectives without undertaking another move north to, once again, carry gunboat diplomacy ever closer to the Qing court. Sir Henry Pottinger—Elliot’s successor as diplomatic “plenipotentiary” and chief superintendent of trade—arrived in Macao in August with instructions from London to do just that.

In the later part of August, the fleet headed north with 14 warships including four steamers—quickly occupying, once again, Amoy (August 26); Tinghai, the capital of Chusan (October 1); and Ningpo (October 13). Amoy was taken with very little opposition, but this was not the case with the other two strategic locales.

|

|

|

| |

Thomas Allom’s panoramic depiction of Amoy, occupied by the British on August 26, 1841, was published a few years later. An English-language account a decade later offered this description of the city: “The town is large and populous, defended by stone walls and batteries, and has, from time immemorial, been a place of great trade, its merchants being classed among the most wealthy and enterprising in the Eastern world.”(Julia Corner in China Pictorial, 1853)

Beinecke Library, Yale University

[Allom_1842_Amoy_Yale]

|

|

|

| |

“The 18th (Royal Irish) Regiment of Foot, At the Storming of the Fortress of Amoy, August 26th 1841”

This highly imaginary rendering of the capture of Amoy picks up an earlier Western characterization of Chinese infantry as “tigers of war.” The term may have been coined around the turn of the century by Christian missionaries, who described Qing soldiers as wearing striped uniforms and caps with small ears on them. It is also said that at the time of the abortive Napier mission in 1834, some Qing troops were deliberately dressed in such costumes in order to intimidate the British emissary. In actuality, after heavy naval bombardment, resistance to the British landing forces at Amoy was slight and the city was entered “without opposition.”

Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library

[1841_IrishStormAmoy_Brown]

|

|

| |

The relatively easy occupation of Amoy was deceptive. By contrast, Tinghai became a “field of slaughter,” in the words of John Ouchterlony, with several “mandarins of note” choosing to die by suicide rather than face the humiliation of defeat and wrath of the emperor.

The taking of Ningpo was equally grim. On this, Ouchterlony’s account devotes several pages to the October 10 battle at Chinhai, a critical fortification at the mouth of the Ningpo River some 50 miles from Chusan. Chinhai, too, became “a dreadful scene of slaughter,” a massacre where British officers were unable to stop “the butchery” by their own troops, a macabre spectacle where most fleeing Chinese were unable “to escape the tempest of death which roared around them.”

Chinese prisoners who did escape this tempest were subjected to petty humiliation of a sort popular through the full course of the war among victorious British troops, who often “deprived” defeated foe of “their tails”—that is, cut off the queues Chinese men were required to wear under the Manchu dynasty. Typically, Ouchterlony’s account of the Battle of Chinhai concludes by reporting that “On the side of the British but few casualties occurred.” After the rout at Chinhai, Ningpo was ripe for the taking, and offered no resistance.

|

|

|

| |

“Capture of Ting-hai, Chusan

From a sketch on the spot, by Lieut. White, Royal Marines”

Thomas Allom’s illustration focuses on British troops being landed under the cover of heavy cannon fire from the big multi-gun warships. Two steamers are visible on the right. Chinese losses were great and ghastly at Tinghai, occupied on October 1, 1841. Temperamentally, Allom never ventured onto such gritty terrain—but neither, by its very nature, did maritime battle art of the Opium War in general.

Beinecke Library, Yale University

[Allom_1841_Chusan_Yale]

|

|

|

| |

“Close of the Engagement at Chin-Hae”

The capture of Chinhai, a strategic fortification at the mouth of the Ningpo River, paved the way for easy occupation of Ningpo on October 13, 1841. John Ouchterlony’s woodcut rendering of the final battle, in which retreating Chinese defenders found themselves trapped by the British landing party, captures the close-quarters nature of the fighting. It fails, however, to convey the full horror of the massacre that Ouchterlony provides in the vivid text in his book.

From The Chinese War (1844), p. 190.

[ou_190a_ChinHae]

|

|

| |

These battles and occupations were prelude to a lull before the final military thrust. Amoy was lightly garrisoned, while the bulk of the fleet wintered over in occupied Chusan and Ningpo. Meanwhile, to the south, British merchants and officials embarked on a construction boom aimed at turning Hong Kong from Palmerston’s “barren island with hardly a house upon it” into the great commercial hub it was soon to become.

Phase IV of Hostilities: March 1842–August 1842

The winter lull in major military activities essentially ended in March 1842,

when British troops suppressed two Chinese offensives in and around Ningpo. On March 10, a bold attempt of thousands of Chinese fighters to take on the foreigners within Ningpo itself ended, as so often, in one-sided carnage when the long column of Chinese, trapped in a narrow street, was mowed down by British muskets and a howitzer spraying grapeshot.

Lieutenant Ouchterlony described this as “merciless horror in the street,” and capped his description with a striking vignette. “The corpses of the slain lay heaped across the narrow street for a distance of many yards,” he wrote, “and after the fight had terminated, a pony, which had been ridden by a mandarin, was extricated unhurt from the ghastly mass in which it had been entombed so completely as to have at first escaped observation.”

|

|

John Ouchterlony’s rendering of the “Repulse at Ningpo” on March 10, 1842,

was accompanied by the observation that “While on our side not a single man had been killed and only a few wounded, upwards of 400 of the enemy had fallen, consisting, of course, of their bravest and best.” John Ouchterlony’s rendering of the “Repulse at Ningpo” on March 10, 1842,

was accompanied by the observation that “While on our side not a single man had been killed and only a few wounded, upwards of 400 of the enemy had fallen, consisting, of course, of their bravest and best.”

From The Chinese War (1844), p. 241

Wikimedia Commons

[ou_240a_Ningpo] |

|

| |

On March 15, five days after this slaughter, the Chinese suffered a comparably harsh defeat at Segaon, in the countryside near Ningpo. Two months after this, beginning in mid-May, the British expedition resumed its push north, greatly replenished by reinforcements from India.

At its peak in this final stage of the war, the fighting force of the fleet (not including scores of transports) was comprised of 15 warships, five steam frigates, and five shallow-draught iron steamers. Total manpower came to 12,000 fighting men, of whom 3,000 were seamen; two-thirds of the latter were also available for deployment on shore.

The British initially intended to attack the strategic city of Hangchow (Hangzhou) in the basin of the Yangtze River north of the Ningpo-Chusan area where they had wintered over. After discovering that the bay there was too shallow to allow entry of their large warships, they turned their attention further north.

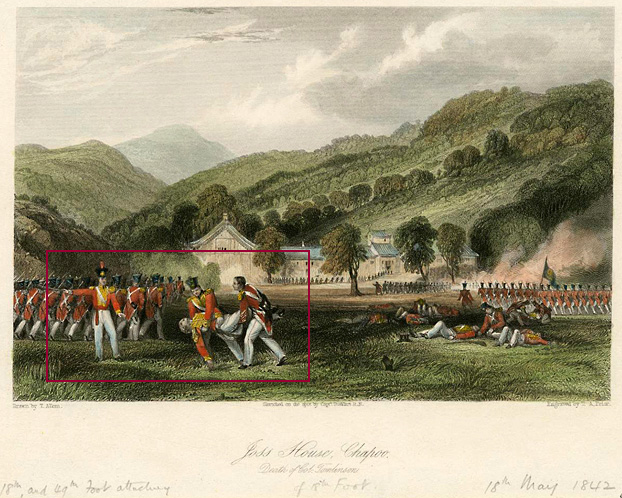

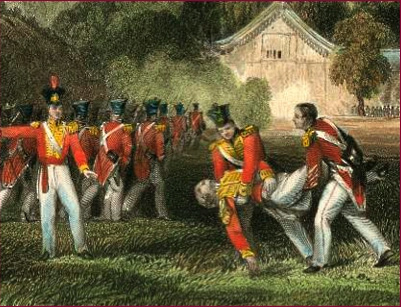

The first noteworthy battle in this final advance came on May 18, 1842, with a British victory at Chapu that provided heroes and horrors in equal measure. Located on the coast between Hangchow and Shanghai, Chapu was known as a “Tartar” city—a misleading term the foreigners commonly used to denote the multi-ethnic cadre of “bannermen”—comprised of Manchus, Mongols, and Chinese—who served as an elite military force for the Manchu rulers. This elite cadre maintained detached residences in the city—and, as it turned out, adhered to a grim, no-surrender culture.

The confrontation at Chapu gave the British a martyred officer: a Lieutenant-Colonel Tomlinson, who died instantly after being struck in the neck by a bullet. (Total British losses at Chapu were 10 killed and fifty wounded, against five to six hundred Chinese dead.) Tomlinson’s fatal encounter occurred near a “joss house”—a building in which an eclectic mixture of saints and deities was venerated—that became remembered for various reasons in subsequent war stories. The colonel was killed there. A large contingent of bannermen barricaded in the building earned the admiration of their antagonists by refusing to surrender. And when the British forces took Chapu itself, they discovered that the cult of death-before-surrender was not confined to the warriors. To their horror, they came upon the corpses of women and children who had taken poison, or been given poison, or been strangled or killed in other ways by their kith and kin when news of the defeat reached town. This was the first time, but not the last, that the invaders confronted such a gruesome response to their offensive.

|

|

|

|

“Joss House, Chapoo. Death of Col. Tomlinson” “Joss House, Chapoo. Death of Col. Tomlinson”

Thomas Allom’s well-known print is particularly striking because battlefield deaths and casualties were so comparatively rare among the British forces. “Col. Tomlinson” became, in effect, a heroic symbol of the civilizing mission the British had undertaken.

Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection Brown University Library

[1842_JossHouse_Brown]

|

| |

“Engagement at the Joss-House near Chapoo”

After “shot, rockets, and musketry” failed, the religious building in which bannermen warriors had barricaded themselves was destroyed by setting it on fire with kindling. John Ouchterlony’s account of this May 1842 battle praises the valor of enemy soldiers who fought to the bitter end.

From The Chinese War (1844), p. 278

[ou_278a_Chapoo]

|

|

|

“Close of the Attack on Shapoo—the Suburbs on Fire,” May 1842 “Close of the Attack on Shapoo—the Suburbs on Fire,” May 1842

Thomas Allom’s depiction of the naval bombardment of

Chapu reduces the burning suburbs to a remote and almost abstract detail,

while focusing on the rescue of unidentified men in the harbor waters.

Beinecke Library, Yale University

[Allom_1842_Shapoo_Yale]

|

| |

One month after Chapu, the British expedition attacked Woosong on the mouth of the Hwangpu River that flows through Shanghai (on June 16), and Shanghai itself three days later. Part of the advance on Shanghai was done on land, with British forces picking up coolie labor along the way. At that time, Shanghai was still a small town—nothing like the major metropolis it became by the end of the 19th century. As usually happened, looting by native residents broke out in Woosong and Shanghai soon after the British had wreaked their destruction.

|

|

| |

“Battle of Woosung”

From an Original Drawing by Capt. Watson, R.N.C.B., published in 1845

Beinecke Library, Yale University

[Woosung_3457-003_yale]

|

|

| |

“Shang-Hae-Heen”

Ouchterlony’s distinctive rendering of Shanghai in 1842 suggests how small and modest the town was at the time. No one could have guessed that in the decades

that followed this would become a great seaport and one of China’s most

cosmopolitan cities.

From The Chinese War (1844), p.305

[ou_304a_]

|

|

|

| |

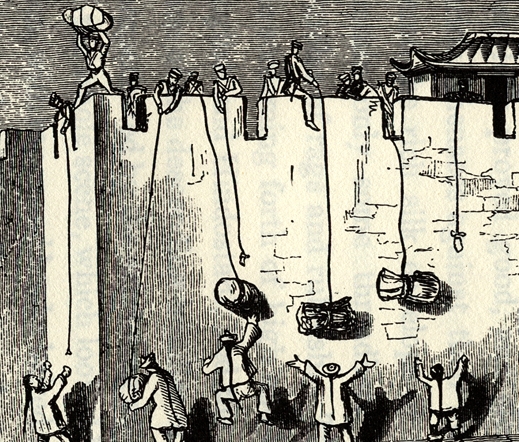

“Sale of Plunder at Shang-Hae”

from The Chinese War (1844), p. 318

[ou_318a_plunder]

Everywhere the British forces attacked, plunder and pillage followed in their wake. Much of this was done by the foreigners. It was taken for granted that silver dollars in particular, whether found in public or private places, were legitimate victor’s spoils; and on more than a few occasions the foreign invaders lit their cooking fires with precious books, beautiful textiles, and once-elegant, now-splintered furniture. In an interesting annotation to Chinese swords from the time now in the collection of England’s National Maritime Museum, it is noted that “The world ‘loot’, from the Hindi ‘lut’, meaning to ‘plunder’ or ‘take forcibly’, became an accepted part of the English language during the First Opium War.”

At the same time, in almost every city the foreigners attacked, mobs of Chinese looters followed in their wake. Such lawlessness was abetted by the fact that British bombardment commonly led urban residents to flee their homes, leaving their abandoned possessions ripe for the picking.

Shanghai was not untypical in this regard. After the opening British cannonade, in Lieutenant Oucherlony’s words, “on pushing forward, the place was found evacuated, and the column marched in without molestation. …Quarters were assigned to the troops, and measures were promptly taken to suppress pillage, but the lower orders of Chinese, the most desperate class of men perhaps existing when excited by the prospect of plunder, swarmed over the place, which had evidently been already for some time in their possession, as many of the principal habitations were found broken open, and thoroughly gutted; and it was with the utmost difficulty, and by having the streets continually patrolled in all directions by strong parties, that the town was preserved from utter ruin by fire and mob violence.”

As Ouchterlony’s “Sale of Plunder” graphic reveals, however, the plunder of Shanghai eventually morphed into a bizarre sort of binational and multiethnic collaboration. On close examination, the figures atop the wall lowering loot to Chinese below are clearly foreigners, and the text that surrounds the illustration paints a vivid word-picture of this raucous ad hoc “bazaar.”

|

|

|

| |

Looters at the top dropped bundles (mostly “silk cloaks and petticoats”) just low enough for bargaining to take place. If a deal was struck, money—usually silver dollars—would flow up while the merchandise descended to ground. “The laughter and the screaming forth of high and low Chinese, of English and Hindostani, and the absurd appearance of the descending bundles of indescribables, compensated by the ascending dollars,” Ouchterlony wrote, “… looked like a fishery for men, with ropes and hooks baited with silk cloaks….”

Ouchterlony found this particular scene “ludicrous and amusing.” Plunder and wanton destruction in general appalled him, however; and, with the wisdom of hindsight, historians also can discern in such mayhem the seeds of chaos and civil disorder that would rock China for decades to come.

|

|

| |

After Shanghai, the British turned their eyes to Nanking (Nanjing), the huge former Ming dynasty capital up the Yangtze River. On July 21, Chinkiang (Zhenjiang), a large walled city at the strategic juncture of the Yangtze River and Grand Canal—150 miles from the sea and 45 miles downriver from Nanking—fell to the invaders in what turned out to be the final major battle of the war.

Close to 3,000 Manchus, Mongols, and Chinese fought stubbornly but vainly against a British force of around 7,000 men in this brief last stand by the Qing military. Much of Chinkiang was destroyed, and thousands of its fighting men and residents perished—under the assault of the foreigners; in a paroxysm of plunder and arson by Chinese mobs and marauders; and, as in Chapu two months earlier, in a frightful communal spectacle of suicide and the killing of family members.

|

|

|

| |

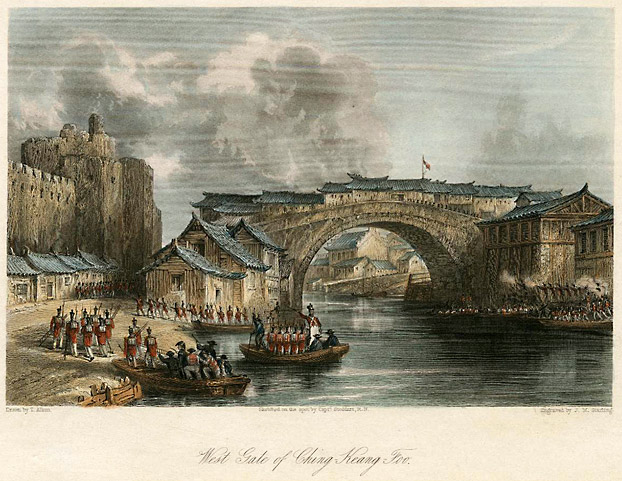

“West Gate of Ching-Keang-Foo,

sketched on the spot by Capt. Stoddard, R.N.”

Thomas Allom’s serene rendering of Chinkiang, the last major battle of the war—typically colorful, typically based on a sketch by a British officer, and typically published considerably after the event—also typically fails to convey the destructiveness and human costs of the battle, particularly on the city’s residents.

Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library

[1842_GhingKeangFoo_Brown]

|

|

| |

Ouchterlony’s rendering of the battle at Chinkiang focuses on the strong Chinese resistance, but fails to convey the horrors experienced within the besieged city.

From The Chinese War (1844), p. 392

[ou_392a_chin]

|

|

| |

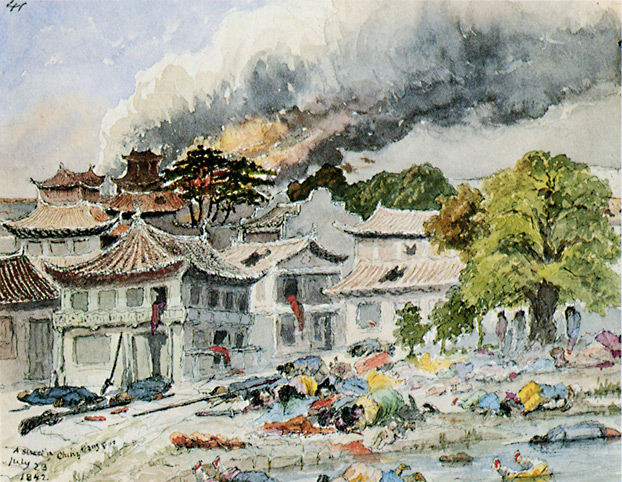

“British Troops Capture Chin-Keang-Foo”

The Battle of Chinkiang, which took place on a scorching day in mid July, 1842, saw more British casualties than usual. The naval surgeon Edward Cree wrote in his journal that “Our loss in killed is estimated at 200, but I never knew of so many deaths from sunstroke in one day. The enemy’s loss is reckoned at 2,000 out of 5,000 said to have been engaged.” More official reports put the British combat casualties at 38 killed and 126 wounded. As always, the real number of dead on the Chinese side could only be guessed at.

Wikimedia Commons

[1842_July1_ChinKeangFoo_wp]

|

|

|

| |

Dr. Edward Cree’s unpublished eyewitness watercolor captures the horrors the victors encountered upon entering Chinkiang. Fires raged, corpses of soldiers lay in the street, and—most horrible of all—as in Chapu two months earlier, bannermen had killed themselves and their families en masse rather than face the rape, plunder, and disgrace of surrender.

National Maritime Museum

[cree_104_Chinkiangfoo_dead]

|

|

| |

“Nanking from the South-East”

Once the British forces had established themselves outside the walls of Nanking, Qing officials finally acknowledged that they had no choice but to give in to such irresistible gunboat diplomacy.

From The Chinese War (1844), p. 453

[ou_452a_Nanking]

|

|

| |

With the fall of Chinkiang, the way to Nanking now lay open. By early

August, the British forces were within firing range of the celebrated

walls of the great city, and Qing officials finally realized the

foreigners were in position to cut off all vital commerce between

south China and the north. The Yangtze region was “like a throat, at

which the whole situation of the country is determined,” Yilibu, the

viceroy of Nanking, observed. The enemy, he went on, had already cut

off the transportation of salt and grain, and impeded the movement of

merchants and travelers. “That is not a disease like the ringworm,” he

continued, carried away by his anatomical metaphors, “but a trouble in

our heart and stomach.”

|

|

|