|

|

The City by Day These street-level views capture details of Tokyo on the cusp of change. Light from both natural and manmade sources suffuses the prints in a way that is distinctive to Kiyochika. The format of these Visual Narratives helps convey the delicacy, detail, and depth of these everyday scenes. Viewers can scroll down through the entire section, or use the menu below. The Visual Narratives are as follows: |

||||

| 1 – The City Unchanged 2 – The Changing City |

1 – THE CITY UNCHANGED Kiyochika revealed a city with its pins knocked out from under it, reeling from the simultaneous collapse of an old system and the quick imposition of a new one. While much has been made of Tokyo’s scramble to absorb the new, less often commented on is the dissolution of the daimyo and samurai structures, leaving once active and vital areas of the city startlingly reduced in population and activity. Vast estates and land holdings were abandoned. The topographical “high ground” of the city, frequently a metaphor for wealth, was open at least for an afternoon’s stroll that offered new vistas. The visual satisfactions achieved by the bird’s-eye view, employed brilliantly by Kiyochika’s predecessors Hokusai and Hiroshige, are effectively brought down to earth, to the realistic heights of the high grounds that rose up beyond the castle. It was Kiyochika’s choice to select and interpret the vista. In this thematic grouping of images, “The City Unchanged,” Kiyochika’s scenes depict a variety of activities in Tokyo, including the river and outlying areas. It follows the tradition of noting the passing of the seasons. The graphics show the artist’s love of the gentle, timeless quietude of a city on the verge of change. |

|

Kameido Umeyashiki, ca. 1880 Kameido, on the eastern side of the Sumida River, was the site selected in 1662 for a shrine dedicated to the spirit of Sugawara Michizane (845-903). Establishment of the shrine was part of a larger effort to disperse dense populations and develop the eastern side of the Sumida River after the devastating Meireki fire of 1657. Known posthumously as Tenjin, Michizane was the patron of scholars. As a high-ranking official in the Heian court he sided with the Emperor Uda’s attempts to throw off domination of the Fujiwara clan. Backing this losing cause led to his banishment to Dazaifu in Kyūshū. Ever after, his spirit not only was the guardian of scholars but also embodied a potential for vengeance on official corruption. His carefully-tended plum tree in Kyoto was said to have miraculously transported itself to Kyūshū to comfort him in exile. Thus, the central Tenjin shrine in Kyushu and auxiliary shrines including this one in Edo were sites of well-tended plum groves. Earlier artists, particularly Hiroshige, had focused on depiction of the most famous of the plums, Garyūbai, or “sleeping dragon” plum. Here, as in other nostalgic scenes selected by Kiyochika, the focus is not on a dazzling composition or unique perspectives but simply on a seemingly satisfied population enjoying a moment of leisure. Men and women relax near a teashop, several of the men notably sporting the Western-style hat in vogue since the early 1870s. [s2003_8_1125] |

|

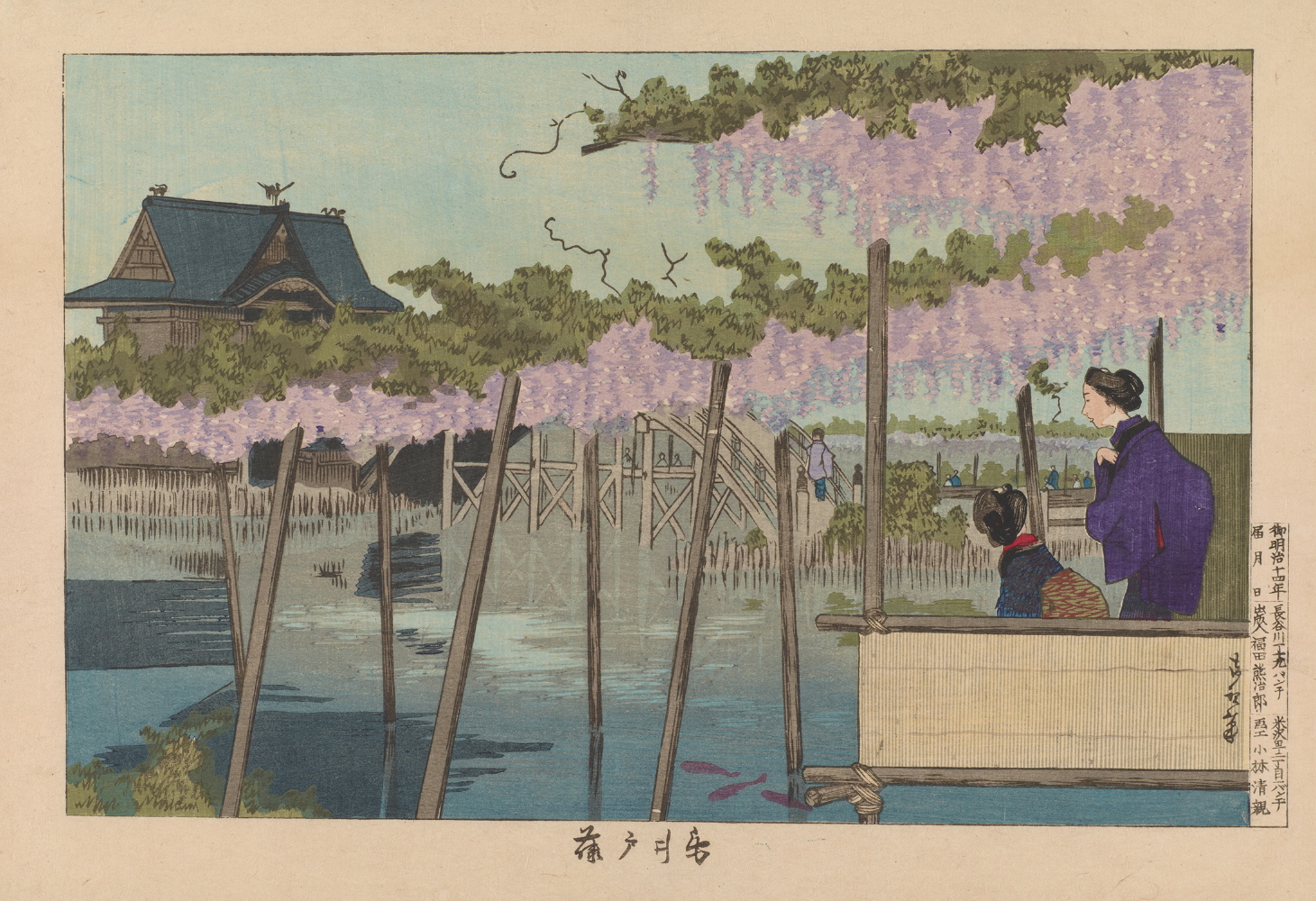

Wisteria at Kameido, 1881 The wisteria, or fuji, is a symbol of the Fujiwara family—ironically, the enemies of Sugawara Michizane and agents of his exile to Dazaifu in the early-10th century. The visitors depicted by Kiyochika may or may not have appreciated the irony of this gentle “subordination” of the Fujiwara within the grounds of the shrine dedicated to this great statesman and scholar. [s2003_8_1133] |

|

Along Shinobazu Pond in the Rain, ca. 1880 Space, vast amounts of space, seems a recurrent theme in Kiyochika’s Tokyo. Thanks in part to the high-ground views, new ways of perceiving the low lands were explored. The crowded and claustrophobic sense of the lower, denser sections of the city are averted. Even marshy river banks open on to seemingly endless expanses of sky, river, and the bay beyond. Kiyochika’s views of the low lying areas of the old city include this homage to Shinobazu Pond. Only a dozen years before the print was created, Shinobazu was within the confines of the Kan’eiji, the great Tokugawa sponsored temple that served as a spiritual sentry for the city at its northeast extreme. The grounds of Kan’eiji were the site of the last major battle between Imperial and Tokugawa forces—an interesting choice of location for a veteran of the losing side. The vantage is from the south shore of Shinobazu Pond with a view of Benten Shrine in the distance. The site was a favored subject for early practitioners of Western-style art in Japan, notably the great painter Takahashi Yuichi (1828-1894) who exhibited the oil painting Evening View of Shinobazu Pond in 1880, the year of Kiyochika’s print rendering. Kiyochika’s desire to emulate Western styles is hinted at in his signature, scribbled out horizontally. As well, perhaps he and his publisher sensed a commercial advantage by linking to an image produced by a more famous artist. A close up look at the profusion of lotus flowers show an almost Impressionist expression of colors, freed of reliance on line and contour. For the keyblock outline, Kiyochika employed softer brown instead of black—a striking departure from the norm of traditional woodblock printing. Map location: #16 [s2003_8_1104] |

|

Morning Sea at Omori, 1880 On the coast of the bay just south of central Tokyo, Kiyochika offers the time-honored view of two seaweed gatherers. He borrows from a view made famous in a print by Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797-1861) but chooses a decidedly up-to-date background. In the distance, the forms of high-masted Western vessels mingle with sails of traditional Japanese ships. The bread-loaf shaped daiba or man-made fortress islands add a foreboding touch. Constructed as part of a series of coastal defenses in 1853 by the military strategist Egawa Tarozaemon (1805-1855), these batteries juxtaposed with Western vessels give a sharply contemporary cast to an otherwise idyllic scene. On the immediate shore at Omori, implied, unseen, and balancing the panorama of naval activity in the distance is the suggestion of the presence of the American zoologist Edward Sylvester Morse (1838-1925), whose discovery of prehistoric artifacts at Omori in 1877 marked the first scientific archeological excavation in Japan. He published his findings in 1879. These discoveries would have been very much in the range of Kiyochika’s awareness. [s2003_8_1165] |

|

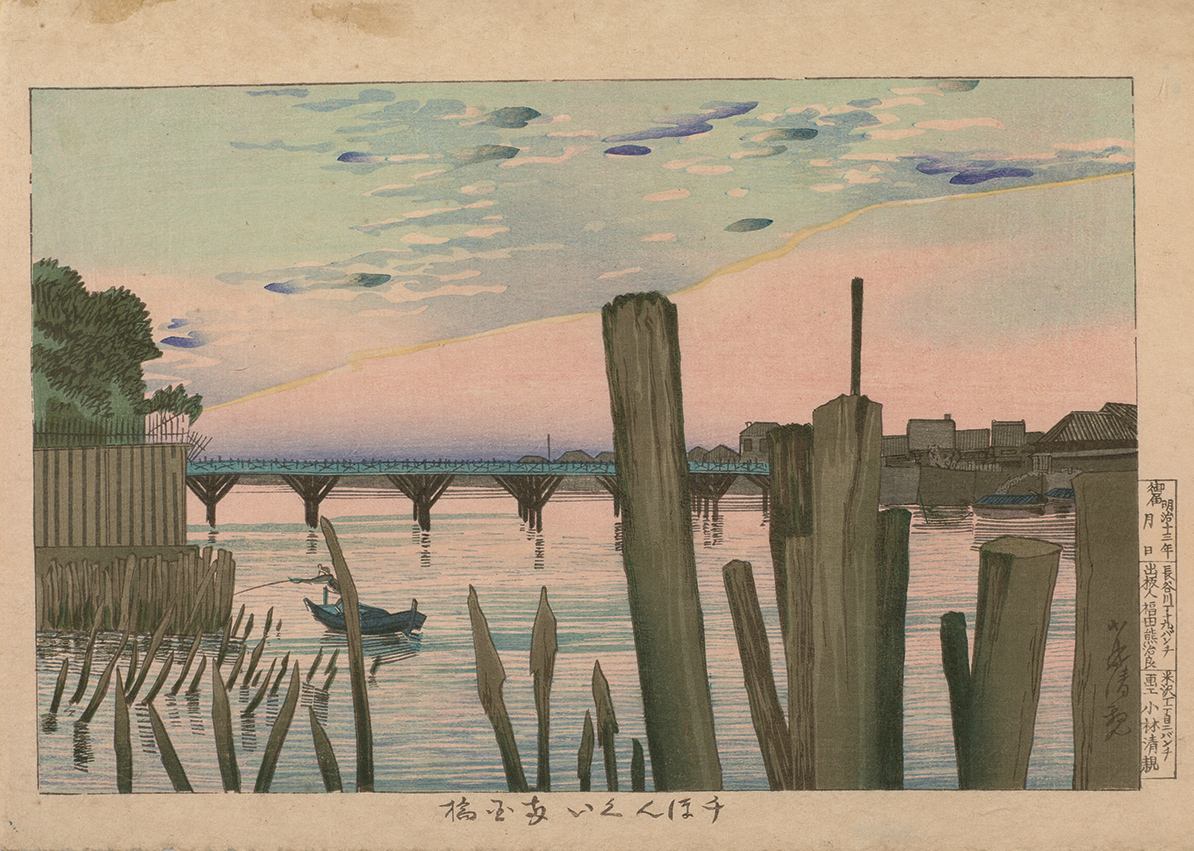

Ryōgokubashi viewed from Senbongui, 1881 A particularly striking perspective of the lowlands, Kiyochika’s view of the Ryōgoku Bridge from Senbongui gives a sense of heroic scale that matches any view from the Tokyo high ground. The view is from the Sumida River’s eastern bank toward the south and the Ryōgoku Bridge at twilight. Viewed at water’s level are a few of the stakes (senbon, meaning “one thousand stakes,” and gui, “a bend in the river”) that protected the banks from erosion. The lone fisherman indicates that Senbongui was a favored fishing location where saltwater and freshwater fish mingled. The stakes provided prime habitats for giant carp, still prized in Edo cuisine. Notable is Kiyochika’s delicate, almost watercolor-like treatment of the skies. In this impression, a thin ray of yellow delineates two states of the atmosphere: clear and burnt pink to the west, rolls and patches of clouds to the east. The color spectrum suggests the transitional hour between sunset and dusk/nightfall. Map location: #17 [s2003_8_1171] |

|

View Inside Ueno Park, 1879 In a scene identified as the interior of Ueno Park, a woman and child approach the gate of a temple. Statues of guardian figures flank the gate, and fencing in front of the gate is vaguely suggested. A sketchily rendered figure, perhaps in military uniform and carrying a rifle, seems to patrol in front of the temple. Several Buddhist structures remained in Ueno Park, remnants of and outlying affiliates of Kan’eij, the great Tokugawa sponsored temple whose precincts comprised much of what became Ueno Park. As well, this large expanse of land was the site of one of the last battles between Tokugawa and Imperial forces in 1868. Its transformation into an area of leisure and culture advanced the aspirations of the Meiji “enlightenment” project and politely erased memories of division and conflict. [s2003_8_1100] |

|

View of Takinogawa, 1878 The maple trees at this scenic point in Oji in the northern Tokyo suburbs were planted by Tokugawa Yoshimune (1684-1751) in the 1730s as a viewing treat for the general populations. Takinogawa (literally, “waterfall river”) was the name given to that stretch of the west-to-east flowing Shakujigawa, which flows into the Arakawa, which again becomes the north-south flowing Sumida River. In the Edo period, the site was close to the Nakasendō, a northerly route to Kyoto, different from the Tōkaidō, which hugged the seacoast. The colorful autumn foliage, distinctive landscape, gorges, and falls made it a popular spot. Kiyochika’s image is populated with several groups of Tokyo ladies. A sense of comfortable respectability and completeness pervades the print. [s2003_8_1146] |

|

View of Street in Hikifune at Ko'ume in Snow, 1878 After the Meireki fire of 1657 the Edo government sought to disperse some of its dense population to the more rural areas to the east of the Sumida River. This required the creation of new transportation and water sources for the population. Just beyond the eastern banks of the Sumida, Yotsuji-dōri—a man-made canal—diverted water from a northerly stream onto a north-south axis, providing drinking water to the growing area of Fukagawa to the south. As Edo’s only tow path it also facilitated transportation to and from the northeast of Edo. The village of Kurume was singled out for depiction because it was approximately there that natural flow from the northeast turned south into the canal proper. As an early engineering feat, it was often depicted but always in a pastoral guise. In this unusual winter depiction, Kiyochika renders two women, one wearing a distinctive combination of hat and veil called the okōsozukin, a kind of retro fashion harkening back to much earlier times. This was perhaps a style counterbalance to the massive infusion of Western-style garb. [s2003_8_1105] |

|

Asakusa Temple in Snow, 1880 The artist reverses Hiroshige’s classic depiction of 1856, in which the viewer sees the temple in a snowy distance at the end of a long entry road. A huge lantern is the foreground device. The scale of the temple, its monumentality, is domesticated by a mother and child—whose garments may suggest a New Year visit—looking outward onto a not-particularly-busy winter scene. The hustle and bustle often associated with images of the great temple is not present. Familiarity rather than bravado is the tone set. [s2003_8_1163] |

2 – THE CHANGING CITY Kiyochika’s portrait of Tokyo evokes natsukashii, a romantic nostalgia for the past. His is not a vision of modernity, but instead a quiet tribute to the pastimes and nuances of life in a beautiful city. Yet, many views are subtly streaked with signs of encroaching modernization. The classic view of Mount Fuji is streaked with electric wires. Western clothing, architecture, and occasionally Westerners themselves enter the traditional scenes. Though the artist presents a graceful city of leisure rather than a jagged city of industrialization—shown, for example, in the ca. 1930s “100 views” by Koizumi Kishio—hints of modernization and militarization intrude into the timeless tranquility. |

|

Clear Weather after Snow at the Old Imperial Palace, 1879 The Imperial Palace is, at the time this print depicts, a rather new concept and designation for the Edo Castle. The residence of the Meiji Emperor from 1868 was understood by Kiyochika as a worthy subject, foregrounded by a line of mounted soldiers. In this print Kiyochika is still some decades distant from the well-articulated military figures found in his images of the Sino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese Wars. But the old castle as a central topic is surprisingly recent. In the acclaimed series of views of Edo created by Hiroshige, only tangential glimpses of this imposing structure are seen. This perhaps reflects the low regard for the shogunate in the 1850s, and also reflects Kiyochika’s perception of the centrality of the imperial concept emerging in the new world order. [s2003_8_1108] |

|

Snow at Ryōgoku, 1877 The single vanishing point again references Hiroshige’s accomplishments. Kiyochika foregrounds the bold shape of open umbrellas as the business of the street, cart-drawn and walking, moves toward an inarticulated distance obliterated by a heavy winter sky. The modern addition of telegraph poles and lines parallels and reinforces the trajectory of movement. [s2003_8_1124] |

|

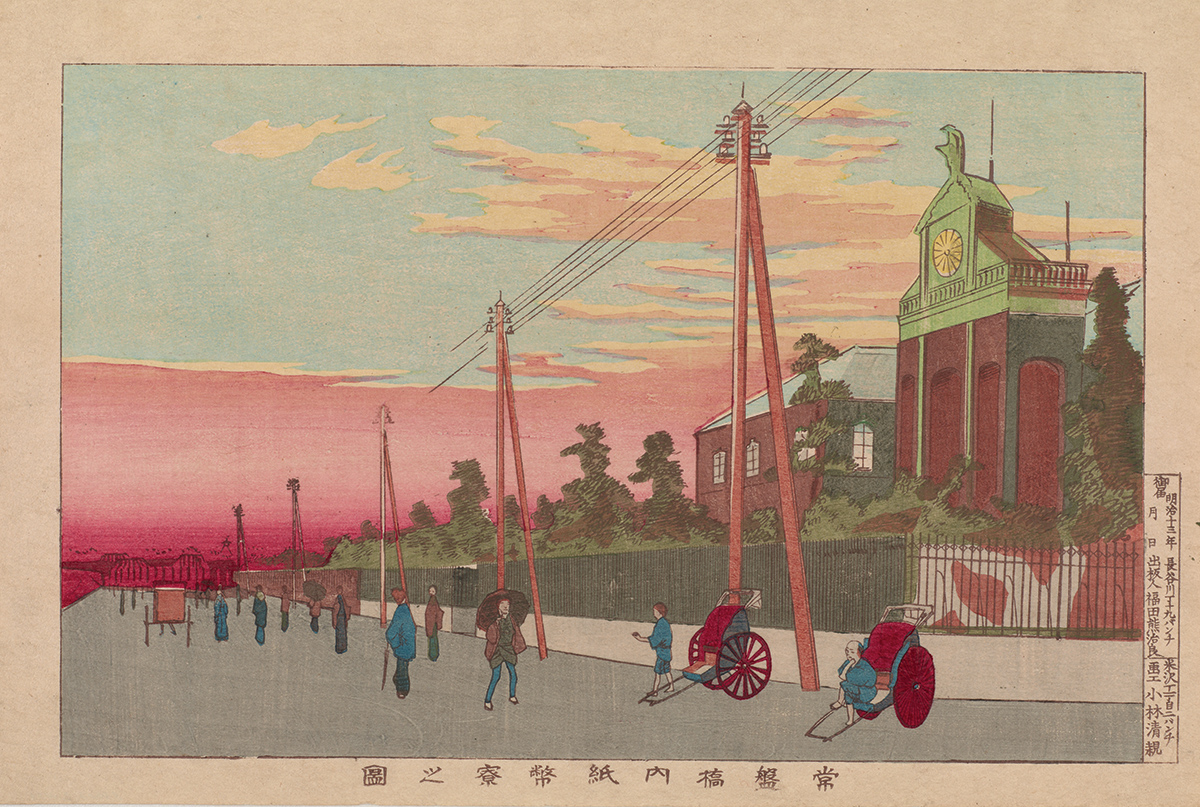

Paper Money Bureau at Tokiwabashi, 1880 The Shiheiryō (Paper Money Bureau) was established in 1871. As demand grew for domestically-produced paper currency, the bureau sought to expand its scope of work to include the design and printing of banknotes, securities, and postage stamps. To this end, Italian engraver Edoardo Chiossone (1833-1898) was recruited to implement Western technologies of ink printing on watermarked paper. The bureau was housed in a two-story redbrick factory building with a phoenix crown, popularly known as Asahikaku (Pavilion of the Rising Sun). In this representation of the building, Kiyochika rendered the dawning sky in pinkish tones. In another, later print, he depicted the scene in broad daylight. Map location: #13 [s2003_8_1138] |

|

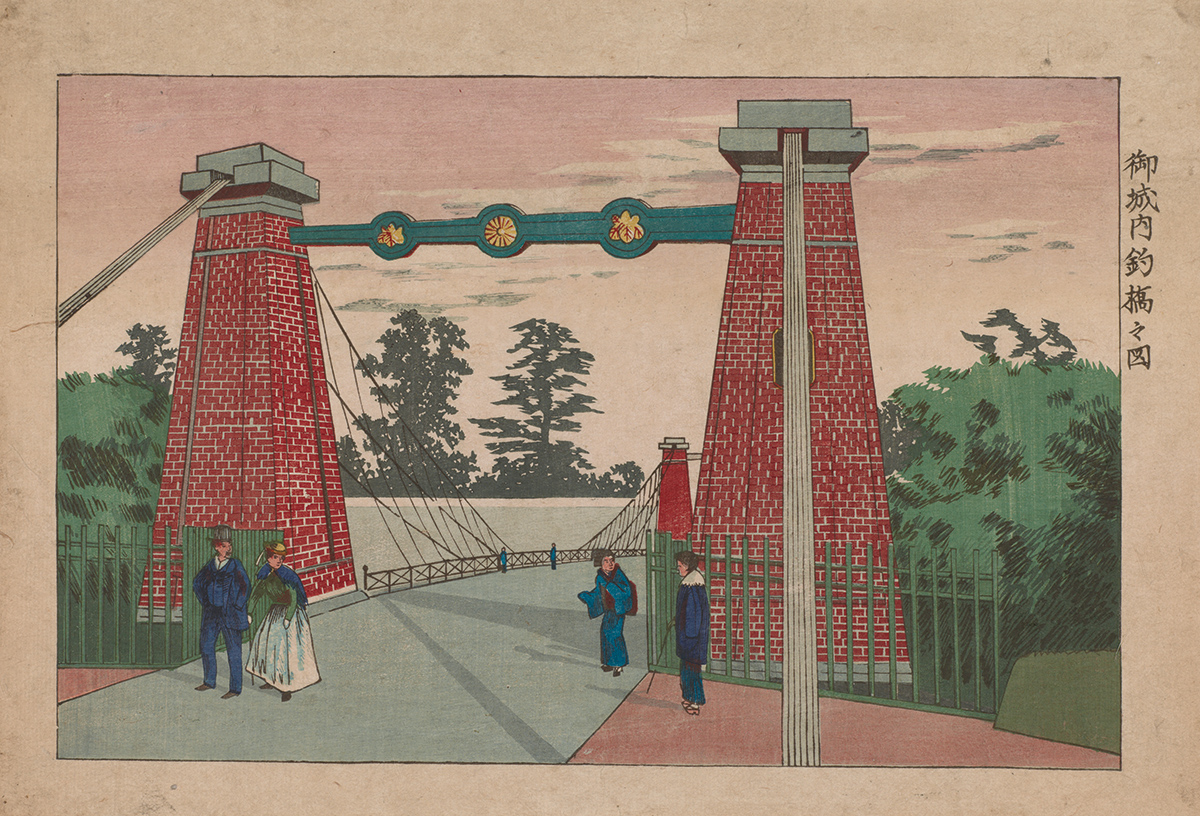

Suspension Bridge on Castle Grounds, ca. 1879 Tokyo’s first suspension bridge was designed by the Irish-born engineer Thomas Waters (1842-1898), one of the many “foreigners for hire,” or resident foreign advisors, working for the Meiji government. Kiyochika depicts the redbrick-and-stucco structure with wire cables and steel braces, the pillar beam adorned with the imperial chrysanthemum crest. The man-and-horse bridge crossed a private moat within the grounds of the Imperial Palace, and in fact was closed to the public. Kiyochika likely relied on photographs to create his design. The couple shown to the left marks one of the few instances that he included Westerners in his Tokyo views. Map location: #9 [s2003_8_187] |

|

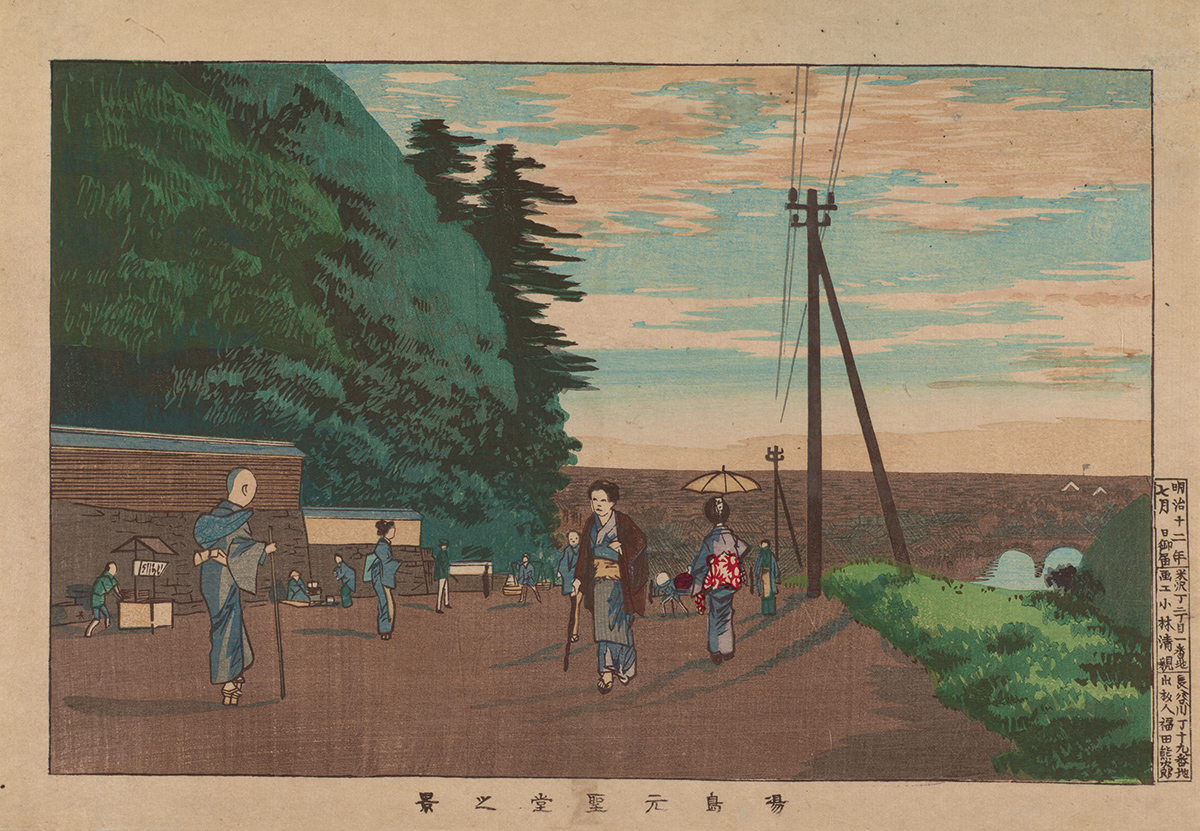

View from the Former Yushima Seidō, 1879 Originally a private school housed in the residence of neo-Confucian scholar Hayashi Razan (1583–1657), Yushima Seidō during the Edo period became the official training academy for Tokugawa samurai. During the Meiji era, the school shared its premises with the Ministry of Education, Tokyo College for Teachers, and Japan’s first state-run women’s college for teachers, earning its appellation as the “birthplace of public school education.” In Kiyochika’s print, the venerable site of learning is obscured behind woods. He offers a prosaic view from atop the slope leading down to the Kanda River. The double arches of Yorozubashi Bridge, nicknamed “four eyes,” are visible from afar. The telegraph wires lead the viewer’s eye to the far distance. Map location: #15 [s2003_8_1142] |

|

Atagoyama, 1878 Atop Atago Hill, the city’s highest natural elevation, two men relax in a teahouse. One wears traditional kimono; the other is in Western clothes. The latter, with his hat, tobacco, and shopping basket, resembles the flâneur look Kafū adopted when he set forth on his city wanderings. Close inspection of the print (for example, around the cloud of smoke emitting from the Western-style figure) shows areas of mesh-like patterns, similar to cross-hatchings used in copperplate lithography. In addition, the waitress’ red and purple accents may have been inspired by hand-tinted photography. Such experimentations attest to Kiyochika’s voracious interest in the variety of new visual media that were just beginning to emerge in Japan. Map location: #14 [s2003_8_1136] |

|

View of Sunrise at Hyappongui, 1879 “Hyappongui” refers to the stakes in the water along the western bank of the Sumida River at Ryōgoku. These pilings were put in place to secure the banks from erosion caused by the current. Again, Kiyochika chooses to create a conceptual counterpoint to the master Hiroshige’s perspective of this same scene. Kiyochika observes from the opposite, western shore, depicting the pilings in the relative foreground. The bridge itself goes unobserved and the early morning quiet, deserted feeling of the scene is in stark contrast to the normal perceptions of the vitality of this area of substantial commerce, connecting the provinces of Musashi in the west and Shimōsa to the east. [s2003_8_1173] |

These prints by Kobayashi Kiyochika are from The Robert O. Muller Collection of the Freer Gallery of Art and the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution |

Massachusetts Institute of Technology © 2016 Visualizing Cultures Creative Commons License |

|

|