|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

Both the British and French called attention to the fact that local Chinese

also took advantage of the chaos at the Yuanmingyuan to help themselves to works

of art and other precious items. Many of these looted goods showed up in the

antique shops at Liulichang, which the British called “Curiosity Street.”

The burning of the palace two weeks later was accompanied by mixed feelings of

triumph, awe, and revulsion. Captain Charles Gordon—later to be famous as the leader of the Ever-Victorious Army against the Taiping

rebels and still later as “Gordon of Khartoum”—wrote home to his mother and sister that after receiving orders to burn the

palace:

We accordingly went out, and after pillaging it, burned the whole place,

destroying in a Vandal-like manner most valuable property, which would not be

replaced for four millions... You can scarcely imagine the beauty and

magnificence of the places we burnt. It made one’s heart sore to burn them; in fact these palaces were so large, and we were so

pressed for time, that we could not plunder them carefully. Quantities of gold

ornaments were burnt, considered as brass. It was wretchedly demoralizing work

for an army. Everybody was wild for plunder.

[6]

As soon as these events occurred, conflicting accusations flew: the British saw

the French as the initiators of the looting, while the French pointed out that

they had not participated in the burning of the palaces. The British had

devised their own method for dealing with the spoils of war: they allowed

soldiers to do some looting, but required them to turn over the goods to a

common pool for later auction. The proceeds were then divided among soldiers

and officers according to rank. Thus much of the loot reached a public market;

items were not necessarily taken home by the individual who had seized them.

Valuable objects from the imperial collections ended up in museums in England

and France. Others were offered for sale at fashionable auction houses in London and

Paris. Still other items were retained in family collections in private homes

all over Europe, but particularly in England.

Victor Hugo’s Letter of Protest

Both the British and French illustrated press published engravings depicting

this vandalism, and the great French writer Victor Hugo expressed his shame

over his country’s actions in scathing words that carry a ring of prophesy to the present day:

One day two bandits entered the Summer Palace. One plundered, the other

burned...Before history, one of the two bandits will be called France; the

other will be called England. But I protest, and I thank you for giving me the

opportunity! the crimes of those who lead are not the fault of those who are

led; Governments are sometimes bandits, peoples never.

Writing to his friend Captain Butler, he wrote emotionally and scathingly of the

wanton destruction of the Summer Palace, which he considered to be “a wonder of the world,” comparing it to the Parthenon in Greece, the pyramids in Egypt, the Coliseum in

Rome, and Notre-Dame in Paris. He said it was a work of the people.

If people did not see it they imagined it. It was a kind of tremendous unknown

masterpiece, glimpsed from the distance in a kind of twilight, like a

silhouette of the civilization of Asia on the horizon of the civilization of

Europe.

He compared Elgin’s destruction of the Summer Palace to the theft of marbles from the Parthenon.

Then, in a voice heard echoed a century and half later, he opined:

The French empire has pocketed half of this victory, and today with a kind of

proprietorial naivety, it displays the splendid bric-a-brac of the Summer

Palace. I hope that a day will come when France, delivered and cleansed, will

return this booty to despoiled China.

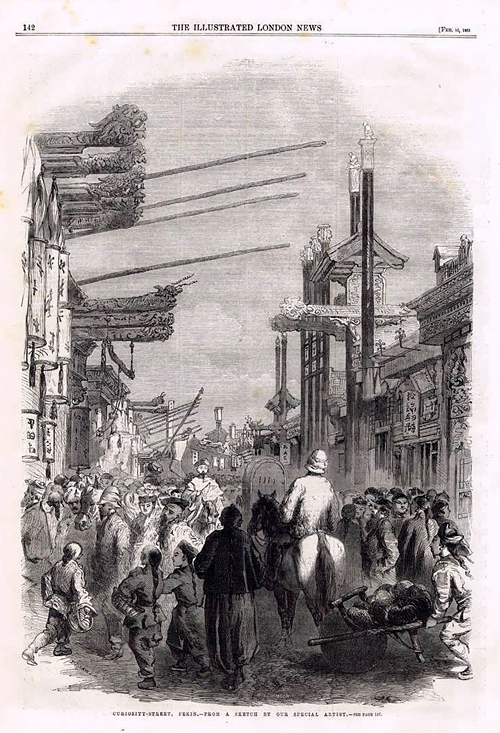

“Curiosity-Street, Pekin,” an illustration in the Illustrated London News, Feb. 16, 1861, shows the market where looted goods were likely to be traded.

[ymy7111] Wikimedia Commons