|

|

Detail from stereograph card with caption:

“Company of Boxers, Tien-Tsin, China.”

This is one of the few existing unstaged photographs of Boxers,

other than depictions of them as prisoners.

© 1901, Whiting Brothers

Library of Congress

[libc_1901_3g03917u]

In 1898 and 1899, masses of Chinese peasants armed with swords and spears began attacking Christian Chinese villagers in the North China provinces of Shandong and Hebei. They called themselves “Righteous and Harmonious Fists” (Yihequan 义和拳), because they practiced martial arts and traditional military techniques. They also called themselves “Righteous and Harmonious Militia” (Yihetuan 义和团), because they claimed to be defending their homes against attacks by foreign bandits and their supporters. Western observers called them “Boxers,” focusing on their use of martial arts techniques, their belief in spells and amulets, and their violent attacks on local Christian communities. By mid 1900, Boxer attacks had spread widely across rural north China, and many groups converged on Tianjin and Beijing. They besieged the foreign legations in Beijing for 55 days and massacred foreigners in the coastal treaty port of Tianjin and in Taiyuan, the capital of Shanxi province.

In response, the armies of eight foreign powers landed in China and marched from Tianjin to Beijing to lift the siege. The foreign armies occupied the imperial palace, while the imperial court fled to safety in Xi’an. The foreigners blamed the Qing court for encouraging the Boxer attacks, as local officials had failed to suppress them or even encouraged them as local militia. After extensive negotiations, the Qing court was forced to sign a treaty providing for execution of guilty officials and a payment of an indemnity of 450 million taels of silver. This amounted to about one ounce of silver per Chinese person, or one and one-half times the annual tax revenue of the dynasty.

Extensive looting of the imperial palace by all the foreign armies, along with public executions of suspected Boxers and massacres during the fighting, further devastated Beijing and north China. But the treaty negotiations—because of rivalries among the imperial powers—left the Qing court in power. Chinese activists in exile, fearing that China would be “sliced up like a melon,” agitated for rapid strengthening of China’s military forces and economy to respond to the foreign threat, and the Manchu court itself launched a reform program in 1905. But it was too late to save the dynasty, which collapsed in the wake of nationalist uprisings in 1911.

The Boxer movement marks a dramatic turning point in the history of imperial China and in the history of imperialism. It attracted more global media attention than any other event in China. Illustrated newspapers and journals, pamphlets, memoirs, and etchings propagated lurid images of savage Orientals and noble Christian martyrs to fascinated audiences in the U.S., Western Europe, Russia, and Japan. More than just a story of rebellion, invasion and negotiation in China, the Boxers were truly a global media event of the highest magnitude. Chinese media played their part too, in the form of woodblock prints glorifying the heroic activities of the Boxers and their military leaders. Amid the cacophony of conflicting images, we can find persisting patterns that illustrate underlying themes of late imperial China’s encounter with foreign expansionism: the struggle of local elites against the penetration of Christian missions; the rise of martial arts groups and local militia to support anti-foreign resistance; foreign Orientalist views of China as a savage, backward country waiting to be redeemed by Christianity and modern science and technology; and the divisions within the Qing court between diehard Manchu defenders of the old ways and mainly Han Chinese proponents of reform.

|

|

|

| |

THE BOXER UPRISING

The Rise of Anti-Christian, Anti-Foreign Movements

After 1860, under the provisions of the treaty settlement of the second Opium War, Western missionaries, like other foreigners, gained the right to travel and proselytize in the interior of China, and Chinese subjects could practice Christianity without punishment. These provisions especially benefited French Catholics, who actively promoted new missionary activity. Unlike the earlier Christian presence in China in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, whose followers were mainly members of the literati elite, this second arrival of Christianity penetrated Chinese villages and small towns, and attracted illiterate peasants.

The first Western Christians, the Jesuits, beginning with Matteo Ricci in the sixteenth century, had aimed to convert the official elite, preaching a doctrine of accommodation between Christian rituals and Confucian ancestral rites. Some late Ming scholars embraced Christian doctrine, and the Kangxi emperor, who reigned from 1661 to 1722, tolerated Christianity until the late-seventeenth century.

|

|

| The Italian Jesuit Matteo Ricci (left) and the Chinese Christian scholar Xu Guangqi (right) in an image from Athanasius Kircher's China Illustrata, published in 1667.

[ricci_wp]

|

|

|

| |

The favorable embrace of Christianity by officials and emperors ended in the eighteenth century, when the Pope rejected the Jesuit assertions of the compatibility of Chinese ancestral rituals and Christian practices. The Pope’s hardline position, along with rivalry between Jesuits and other Catholic sects, doomed official approval of the Christian mission to China. Once the emperors, suspicious of the Pope’s political influence, banned the foreign religion, it survived only underground, in remote communities. By contrast, the missionaries who arrived in the nineteenth century, instead of trying to convert the emperors and local elite, aimed directly at the villagers and townspeople. Unlike the early Jesuits, they regarded the gentry elite as their main rivals. Most nineteenth-century Protestant and Catholic missionaries, firm believers in the superiority of their creed, were intolerant of traditional Chinese rituals, because they aimed at a total transformation of Chinese values.

The gentry, for their part, saw the foreign religion as the main threat to their local power. They attacked Christianity as a heterodox doctrine that would undermine the moral purity and political stability of the empire. Missionaries could offer food, charity, and orphanages to their followers, and they could protect converts who quarreled with other villagers. Impoverished villagers who converted found that they could gain new powers. They could, for example, ride in sedan chairs, resist taxes, wear foreign clothing, and gain foreign backing for lawsuits over property. Officials could not challenge the Christian converts because foreign diplomats and gunboats protected them. Converts refused to participate in local village festivals, while many of the Catholic missions acquired large amounts of land. From the point of view of many villagers and their gentry leaders, Christians were an alien, disruptive force.

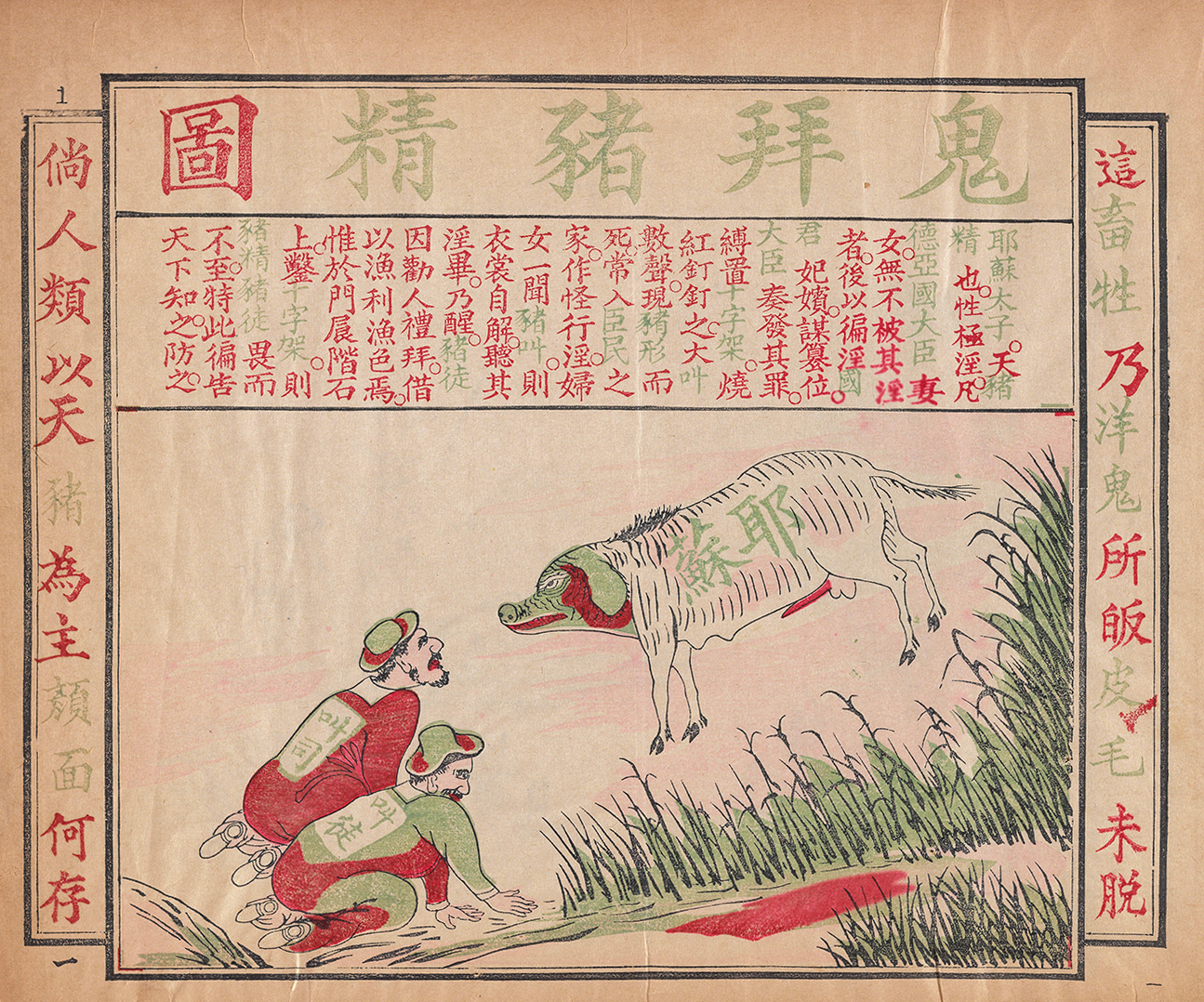

Gentry writers, reviving an old tradition of the seventeenth century, began to circulate anti-Christian tracts which contained both rational arguments against Christian doctrine and emotional denunciations depicting the foreigners as animals and demons with dangerous supernatural powers. Making a play on words on the Chinese words for “Lord” and “Pig” (zhu), they portrayed Christianity as pig worship, involving blood sacrifices.

|

|

|

|

Caption (translation): “The Devils (foreigners) worshipping the Hog (Jesus),” from The Cause of the Riots in the Yangtse [Yangzi] Valley,

published 1891 in Hankou.

[cr75_01]

|

|

| |

The text of this image, part of a long illustrated anti-Christian pamphlet states, “If these men worship a Heavenly Hog as their Lord, where is their sense of shame?”

Chinese villagers, hearing that the communion mass involved consuming the blood of Jesus, concluded that Christians had an insatiable need for blood. They assumed that Christian churches accepted orphans and abandoned children only to extract their blood. Gentry pamphlets abetted these fears, accusing Christians of outrageous sexual practices, disloyal gatherings, and dangerous plotting against the state. These pamphlets, beginning in the 1860s, instigated violent attacks against Chinese converts and missionaries across the empire, culminating in a major diplomatic crisis after the “Tianjin massacre” in 1870, in which a French official was killed after discharging a revolver into a hostile crowd. After the French demanded indemnities, the court punished the local officials responsible for the riot, but general hostility to missionaries continued to grow. By the late-nineteenth century, attacks on Christians, lawsuits, and resistance to missionary activity had spread through many of north China’s cities and parts of the countryside.

Origins of the Boxers

The Boxers came from an ecologically fragile, impoverished region of Shandong province. This area, whose peasant farmers could only barely scrape out a living, had for a long time suffered from frequent natural disasters. From 1852 to 1855, when the Yellow River shifted its course from the south to the north of the Shandong peninsula, massive floods struck the whole province and destroyed commerce on the Grand Canal, the lifeline of the marketing system. Foreign competition and the closure of the Grand Canal damaged the market for cotton, which was almost the only crop that provided farmers with cash income. Banditry flourished everywhere, and the local officials were helpless to suppress it.

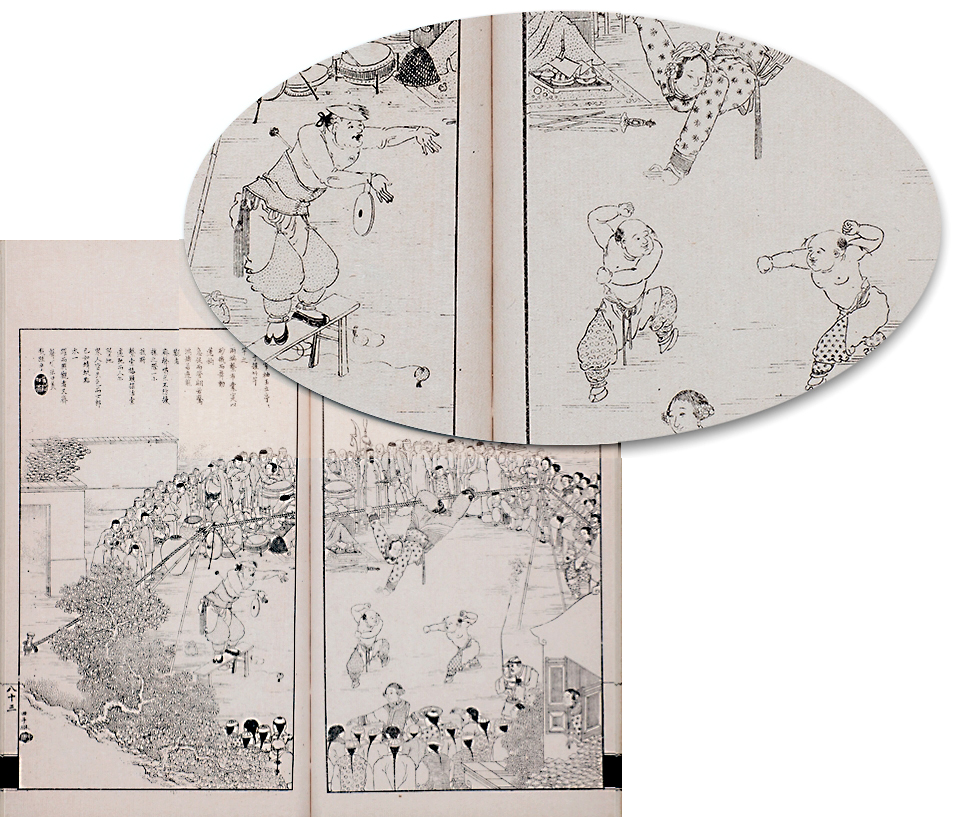

In the poor districts of Shandong, very few men could afford enough education to obtain examination degrees, so the imperial culture of obedience to civil officials and respect for classical learning had little impact. Instead, the people of Shandong’s periphery took pride in their military skills. Outlaws of the Marsh, a famous novel of the sixteenth century, widely read and retold by storytellers, had celebrated a band of martial arts fighters from southern Shandong. These strongmen fought tigers, engaged in drunken brawls, and like Robin Hoods defended local people from abuse by the wealthy. Martial arts teachers founded schools that taught young men special fighting techniques, and rival schools fought each other in competitions in the marketplaces. Other people could hire these toughs to help them out in local brawls. This image from a popular illustrated newspaper shows a crowd of people watching an exhibition of martial arts and gymnastics. The Boxers made their living by traveling around the countryside to perform before such audiences.

|

|

|

| |

“Exhibition of Boxing and Acrobatics” with enlarged detail of “Boxer.”

From Dianshizhai huabao 35, GX 11 (1885), 2nd month.

[dz_v04_036_boxers]

|

| |

In addition, popular culture supported practices like spirit possession which were quite alien to the orthodox Confucian literati. People believed that these shamans could enter a trancelike state which gave them access to divine powers. Local village operas celebrated the feats of great generals of the past and divinely inspired mediums, giving weak, impoverished people hope that the gods would relieve their suffering in a time of extraordinary calamity.

|

|

|

| |

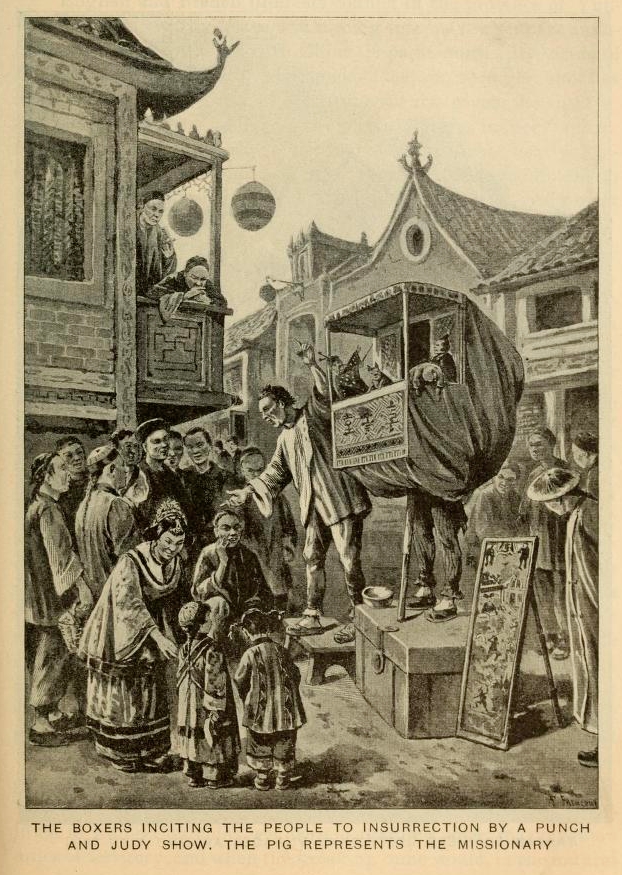

“The Boxers Inciting the People to Insurrection by a Punch and Judy Show. The Pig Represents the Missionary.”

Originally printed in The Illustrated London News, August 25, 1900.

Graphics like this show the pervasive impact of popular theatre in Chinese towns. Some of the theatrical performances used the themes represented in the anti-Christian pamphlets. They were widely disseminated in books like the one reproduced here, Massacres of Christians by Heathen Chinese, and Horrors of the Boxers by Harold Irwin Cleveland, published in Philadelphia in 1900.

[massacresofchris00clev_0539]

|

|

| |

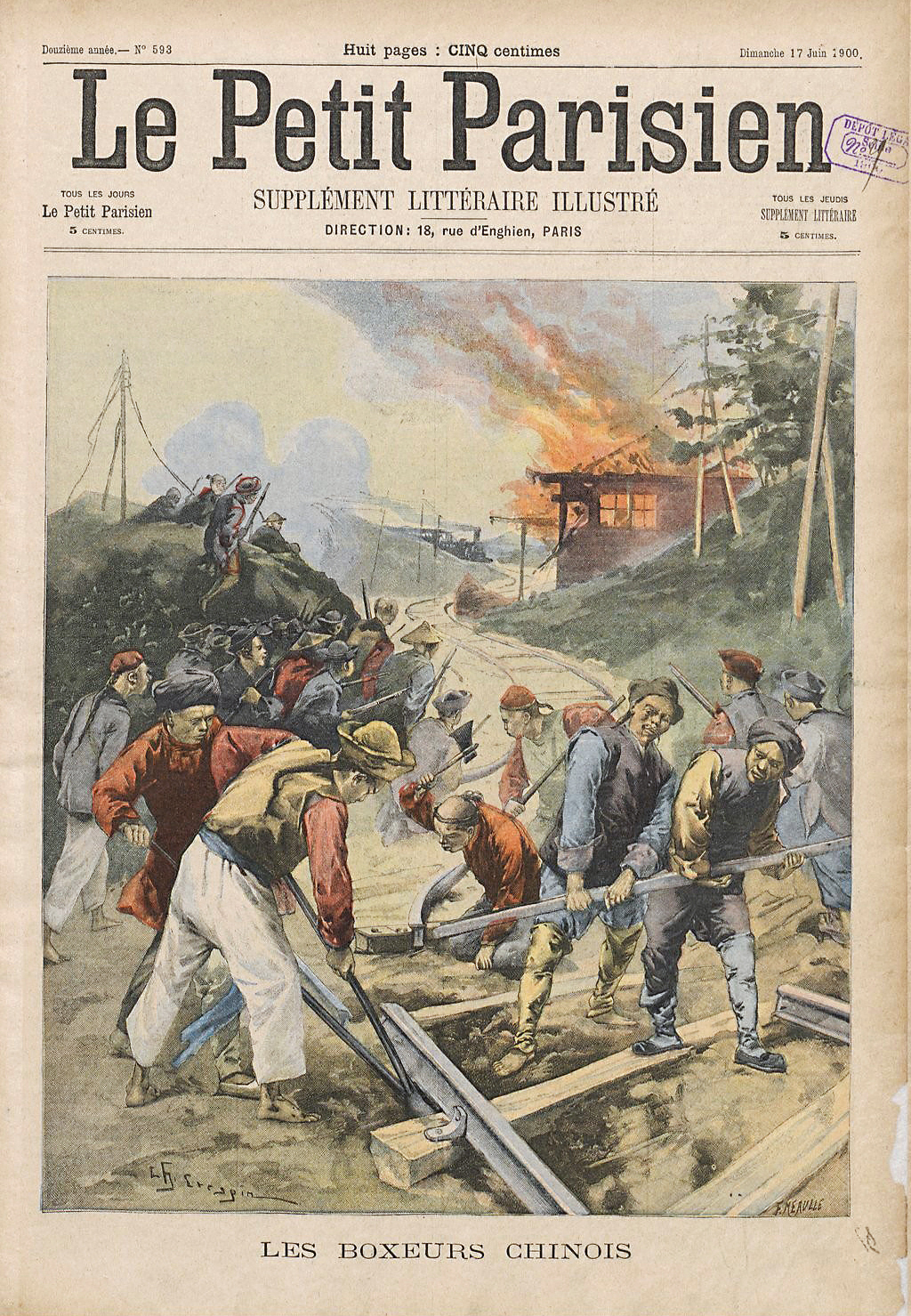

When a drought struck Shandong in 1900, desperate, starving farmers looked for scapegoats. Interpreting the drought as Heaven’s wrath against the moral decadence caused by Christian converts, they attacked all signs of foreign influences and anyone who relied on the missionaries’ protection. Germany, having seized the Shandong town of Jiaozhou in 1897, aggressively expanded the activities of German Catholic missionaries, stimulating nearly a thousand incidents of attacks on converts and foreigners. These attacks spread to destruction of railroad and telegraph lines. The villagers, egged on by local elites, destroyed these modern communications and transportation systems both as a violation of fengshui, the harmonious interaction of humans with their landscape, and as potential routes of invasion by foreign powers.

|

|

|

| |

Boxers destroy railway tracks in this cover illustration of a French periodical.

“Les Boxeurs Chinois”

Le Petit Parisien, Supplément littéraire illustré, Paris, June 17, 1900

Artist: Fortuné Louis Méaulle

[lpp_1900_17July] |

|

| |

As the Boxers rampaged across Shandong, conservative officlals at the court convinced the empress dowager, grandmother of the ruling emperor and the real power behind the throne, to view them as a useful tool for resisting foreign pressure. She told provincial officials not to suppress the Boxers. Although Shandong Governor Yuan Shikai defied her order, the Boxer groups moved north, encouraged by the top officials of Zhili (modern Hebei) to converge on Beijing. By June 1900, the Boxers, supported by Qing troops, had killed the chancellor of the Japanese mission and the German ambassador, burned the British summer legation west of Beijing, and cut off telegraph contact with the city. The legation quarter in the southeast district of the city came under siege.

|

|

| |

“Les Événements de Chine. Carte du Théatre de la Guerre”

Le Petit Journal Supplément Illustré, July 8, 1900

This map, published in 1900, shows the main theatre of war (encircled by the red line), the railroads, and the main foreign possessions in East Asia.

Source: Widener Library, Harvard University

[lpj_1900_07_08_widener]

|

|

| |

An obviously staged photograph of a “Boxer” (below) was widely distributed by foreign news agencies in 1900. This man represents one of the Boxer fighters who was recruited into the officially sponsored Qing militia. Despite the fact that most of the Boxers were poor peasants fighting in warm weather, the man is dressed in warm, newly issued clothing. He wears a distinctive hat, and waves a banner stating “Imperially Commissioned Righteous Militia.” It is of interest for its presentation of martial equipment associated with the Boxers, such as the woven shield and heavy pole topped by a short blade.

|

|

| |

A widely circulated, clearly staged photograph of a Chinese “Boxer”

with pike, shield, and a banner stating “Imperially Commissioned

Righteous Militia,” ca. 1900.

Source: Wikipedia

[us_1900_Boxer_WarConfCD]

|

|

|