| |

SITES OF PROTEST

Hamaya’s photographs of the Anpo protests form a unique record shaped by his style as a photographer, his understanding of the protests, and his literal positioning in relation to the events he was photographing. By all accounts he began covering the protests out of a sense of solidarity with the protestors and an awareness that he was living through a historical moment. [22] His afterword to the published Japanese selection of his photos of the demonstrations is a heartfelt indictment of factionalism and money politics and a defense of the student protestors—whom many others criticized for their extremism—as a natural outcome of government that excludes the voice of the people. “It wasn’t international communism that created the students the government saw as enemies, but Japanese politics and the institutionalized violence (bōryokushugi) among Japan’s politicians.”

|

|

|

It was these convictions that drove Hamaya to follow the protests with such energy. He demonstrates a preternatural ability to be present at their most intense moments, and as the protests grew he got ever more caught up in their trajectory, often not returning home. It was these convictions that drove Hamaya to follow the protests with such energy. He demonstrates a preternatural ability to be present at their most intense moments, and as the protests grew he got ever more caught up in their trajectory, often not returning home. |

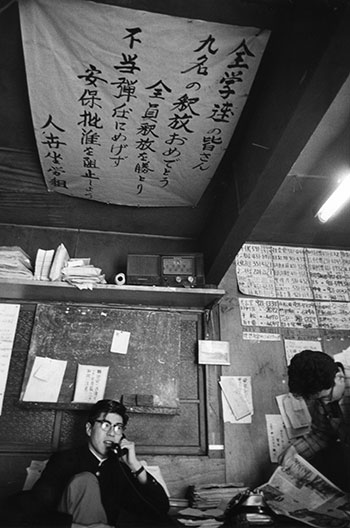

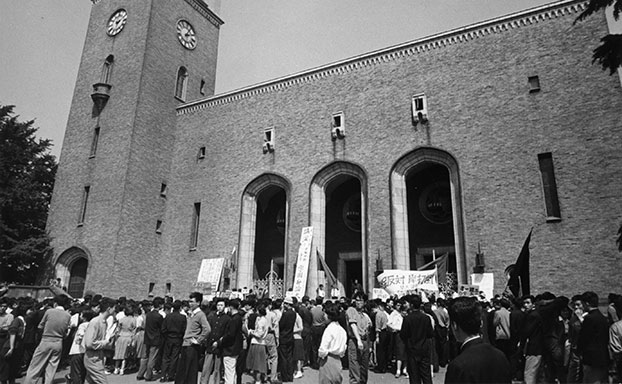

During the protests, Hamaya was assisted by Kurihara Tatsuo, a student at Waseda University and member of the photo club. Kurihara introduced Hamaya to some of the leaders of the radical student organization Zengakuren. The photo to the left is probably at Waseda, inside Zengakuren offices. The banner on the ceiling is from a labor union congratulating the students on the recent release of nine of their members from police custody. Below, students gather at Waseda University on June 3. During the protests, Hamaya was assisted by Kurihara Tatsuo, a student at Waseda University and member of the photo club. Kurihara introduced Hamaya to some of the leaders of the radical student organization Zengakuren. The photo to the left is probably at Waseda, inside Zengakuren offices. The banner on the ceiling is from a labor union congratulating the students on the recent release of nine of their members from police custody. Below, students gather at Waseda University on June 3.

[anp7007] [anp7002]

|

|

| |

The events that Hamaya covered in May and June correspond to the major episodes that feature in most histories of the protests. He begins with a student demonstration on May 20, the day after Kishi’s actions in the parliament, a day that saw many protests. He follows the marches, rallies, and signature campaigns that were part of the People’s Council’s united actions. He was on the scene at Haneda Airport on June 10, when Eisenhower’s press secretary James Hagerty was mobbed by protestors and trapped for almost an hour inside his car. He records moments from the three nationwide general strikes of June 4, June 15, and June 22.

Hayama’s devotion to recording the experience of the protestors is most evident in his proximity to the turbulent events of June 15. The protests on this day were some of the largest and most violent. Students of Zengakuren broke into the Diet compound through the south gate, clashing with police many times in the process. Hamaya remained through the entire confrontation, capturing a moment that was to become a great turning point in the protests.

In the days following, he was attendant at the mourning ceremonies for Kanba Michiko, a female student who was killed in the clashes of the 15th. Scenes of mourning for her blend into dispirited reactions when the treaty passed into law on June 19. But Hamaya ends his account on an upbeat note, with the general strike on June 22, where he shows how the spirit of democratic struggle had not been extinguished.

One of the recurrent tactics of the protestors was to insert themselves into places where their presence would disrupt the forces that lay behind the Anpo treaty. In many of these places Hamaya’s photographs portray the protestors tearing down gates and scaling walls, refusing to be held by barriers to participation. The most startling example of protestors inserting themselves into places and processes they were never invited to was during Press Secretary Hagerty’s visit to Japan.

|

|

| |

The Hagerty Incident

On June 10, President Eisenhower’s press secretary James Hagerty arrived to work out plans for the president’s upcoming visit to celebrate the revised security treaty coming into effect. While attempting to leave the airport at Haneda to go to the U.S. embassy, Hagerty’s car was mobbed by protestors and he had to be rescued by a Marine helicopter.

This incident alarmed official Washington and led the Kishi government to cancel Eisenhower’s visit out of fear that it might be marred by similar protests. This humiliating turn of events did not prevent the treaty from coming into effect, but it did prompt Kishi’s June 19 resignation as prime minister.

|

|

|

Hagerty confers with his aides. Hagerty confers with his aides.

[anp7129]

|

| |

The crowd surrounds Hagerty’s limousine and prevents it from moving.

The “Break Down Lower House” banner in the foreground (displayed by a day-laborer union from Tokyo’s Shibuya ward) is an appeal for dissolution of the Diet. This would have prevented the ratification of the security treaty that Kishi rammed through the parliament on May 19 from automatically going into effect.

[anp7131]

|

|

| |

Eisenhower’s envoys are rescued by a U.S. Marine helicopter after being immobilized by the mob for almost an hour.

[anp7132]

|

|

The protestors at Haneda were joined by a conspicuously smaller contingent of conservative and right-wing counter-protestors waving American and Japanese flags as well as signs of welcome. Both sides were acutely aware of the international press coverage Hagerty’s visit was attracting, and used English as well as Japanese in their placards and banners. The protestors at Haneda were joined by a conspicuously smaller contingent of conservative and right-wing counter-protestors waving American and Japanese flags as well as signs of welcome. Both sides were acutely aware of the international press coverage Hagerty’s visit was attracting, and used English as well as Japanese in their placards and banners.

Protestors urge Hagerty

to “go away.”

[anp7126]

|

|

|

Flag-waving supporters of the revised treaty welcome Eisenhower’s advance party “with open arms.” Flag-waving supporters of the revised treaty welcome Eisenhower’s advance party “with open arms.”

[anp7016]

|

| |

On June 11, the day following the debacle at Haneda, protestors gathered at the prime minister’s official residence, where Kishi and Hagerty were meeting. Hamaya’s photos of this demonstration include exuberant students kicking at the graffiti-smeared wall of the compound.

|

|

|

| |

The most important focal point for demonstrations was the National Diet, whose ziggurat-like structure would figure in many photographs and artistic representations of Anpo over the decades. In Hamaya’s photos, the Diet and its immediate surroundings appear in a number of different attitudes. Although the house of Japan’s representative democracy, in one photo it rises behind a wall formed by police trucks with wooden barriers attached to them. Framed on a slight angle, the seat of Japanese democracy appears to have been knocked off balance. In another photo, taken from a similar position, the space in the foreground has been filled with a group of protestors sitting down, apparently listening to a speech off-camera. The Diet stands straight at the exact center of the background as if this is its proper place, surrounded and protected by the people.

|

|

|

| |

In this photo of the Diet building blockaded by police trucks with wooden barriers attached to them, Hamaya’s slightly off-balance composition conveys a deliberate sense of democratic disequilibrium.

[anp7133]

|

|

This photograph illustrates two consistent features of Hamaya’s technical and stylistic approach: his framing of crowds so that they overrun the picture frame, and his use of deep focus. Framing the images this way makes it difficult to judge a crowd’s size, and raises questions about how the group relates to the spaces around it. Deep focus, which keeps all planes in focus from foreground to background, captures the size of some crowds, and allows the viewer to pick out individuals; the crowd appears as a collection rather than an undifferentiated mass. This photograph illustrates two consistent features of Hamaya’s technical and stylistic approach: his framing of crowds so that they overrun the picture frame, and his use of deep focus. Framing the images this way makes it difficult to judge a crowd’s size, and raises questions about how the group relates to the spaces around it. Deep focus, which keeps all planes in focus from foreground to background, captures the size of some crowds, and allows the viewer to pick out individuals; the crowd appears as a collection rather than an undifferentiated mass. |  |

A crowd of protestors listening to a speech sits squarely in front of the A crowd of protestors listening to a speech sits squarely in front of the

Diet building, as if they were its democratic defenders. The banner on the left indicates that they are members of the Communist Party.

[anp7104]

|

| |

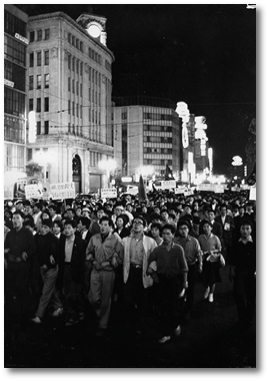

One can see Hamaya’s decision working clearly by comparing two versions of a shot in which a group parades down one of the main thoroughfares of the Ginza, Tokyo’s upscale shopping district. If we compare the original shot with the one that Hamaya included in his photo book, we can see how his cropping of the picture has reframed it significantly. While the un-cropped picture simply shows a crowd walking down a street in the Ginza, in the cropped picture the crowd itself defines the ground, unmooring the lights in the background so that they seem to stand on a sea of people. More often than not, the people in Hamaya’s photos are not attacking barriers, but simply taking over the space they have chosen to occupy. The crowds of people become the center of attention, and simply in their overwhelming presence they redefine the space’s functioning.

|

|

|

As seen in this juxtaposition, the powerful impact of Hamaya's images often reflected his skill at cropping photos in a manner that emphasized the presence of the crowds. As seen in this juxtaposition, the powerful impact of Hamaya's images often reflected his skill at cropping photos in a manner that emphasized the presence of the crowds.

left: Original photograph

below: Cropped version

[anp7121]

|

|

| |

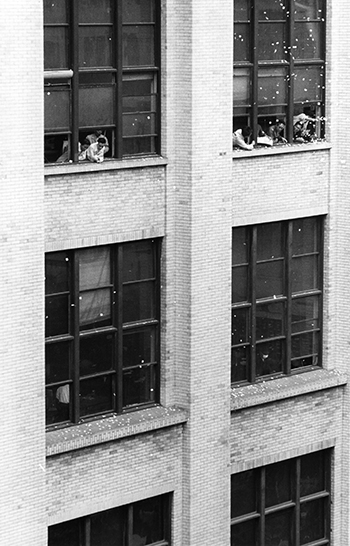

If people from all walks of life came into familiar spaces to complicate them with their presence, the protests also went the other way, infiltrating the more mundane spaces of daily life. During the three general strikes of June, people all over the country participated in political movements from their workplaces. Workers at Tokyo’s central post office threw paper out of the windows, almost like tickertape, and the caption in Hamaya’s book tells us that there was a crowd of protestors below them. The protests were not only on the street, but also at offices, shops, and train stations. The strikes were particularly significant because they did not include any labor demands; they were purely out of sympathy with the demands of the protests. The main industrial unions were joined by large numbers of small shop owners who also decided to shut down.

|

|

|

left: On June 4, workers at Tokyo’s central post office throw paper out of the windows in support of the protests. This was the first of three general strikes that month. left: On June 4, workers at Tokyo’s central post office throw paper out of the windows in support of the protests. This was the first of three general strikes that month.

[anp7124]

below: Shopkeepers showed solidarity with strikers and protestors by shutting down their businesses. Here, a group of shopkeepers march on June 18.

[anp7051]

|

| |

In one photo, youngsters on the way to school stop to add their signatures to a petition against the treaty. Thus, while the Anpo protests were fought over fundamental issues of democracy, international alignment, and peace, they reached deep into the everyday places where people lived their lives. They were both an expression of, and a forum for, people’s understanding of how these issues touched their own lives.

|

|

| |

Schoolchildren add their names to a signature campaign against the treaty.

[anp7135] |

|

|