| |

CONQUEST BY CAMERA

After their rapid military defeat of Spanish forces in the Philippines in August 1898, Americans raised their flag over territory that was more than 8,000 miles away from Washington.

|

|

| |

Original caption on stereograph: “The Stars and Stripes Floating over the Walls of Old Manila, P.I.,” stereograph, 1901

Source: Library of Congress

[view]

[ph117_1901_LOC_3c37903u]

|

|

| |

Soon, however, the Americans found themselves confronting the Philippine Revolutionary Army—men and women who had been fighting against Spain since 1896, had declared an independent Philippine Republic in June 1898, and were unwilling now to be handed over as a prize of war from Spain to the United States. By February 1899, tensions turned to all-out war, which would continue at least until 1902, with sporadic violence for a decade to come.

The camera was one of the many weapons that American soldiers wielded. It helped the military map the terrain, identify the enemy, and document their destruction.

While the photographic apparatus of 1898 may look slow and cumbersome to our eyes, the camera was among the most technologically advanced and complex portable technologies that American soldiers carried into battle, and the Army understood that mastering the photographic image would be key to waging war. The Philippines was almost completely unknown to the U.S. military when they arrived in 1898. With few maps and uncertainty about the reliability of native informants, photographs offered a rapid means of understanding the terrain of battle, and within months the Army had compiled dossiers of photographs of key fortifications, roads, and bridges, using this information to trace the transportation and communication networks of the Spanish and Philippine armies.

Of greatest popular interest both then and today, however, the camera captured the American forces and their Filipino adversaries and allies in a great range of poses and situations.

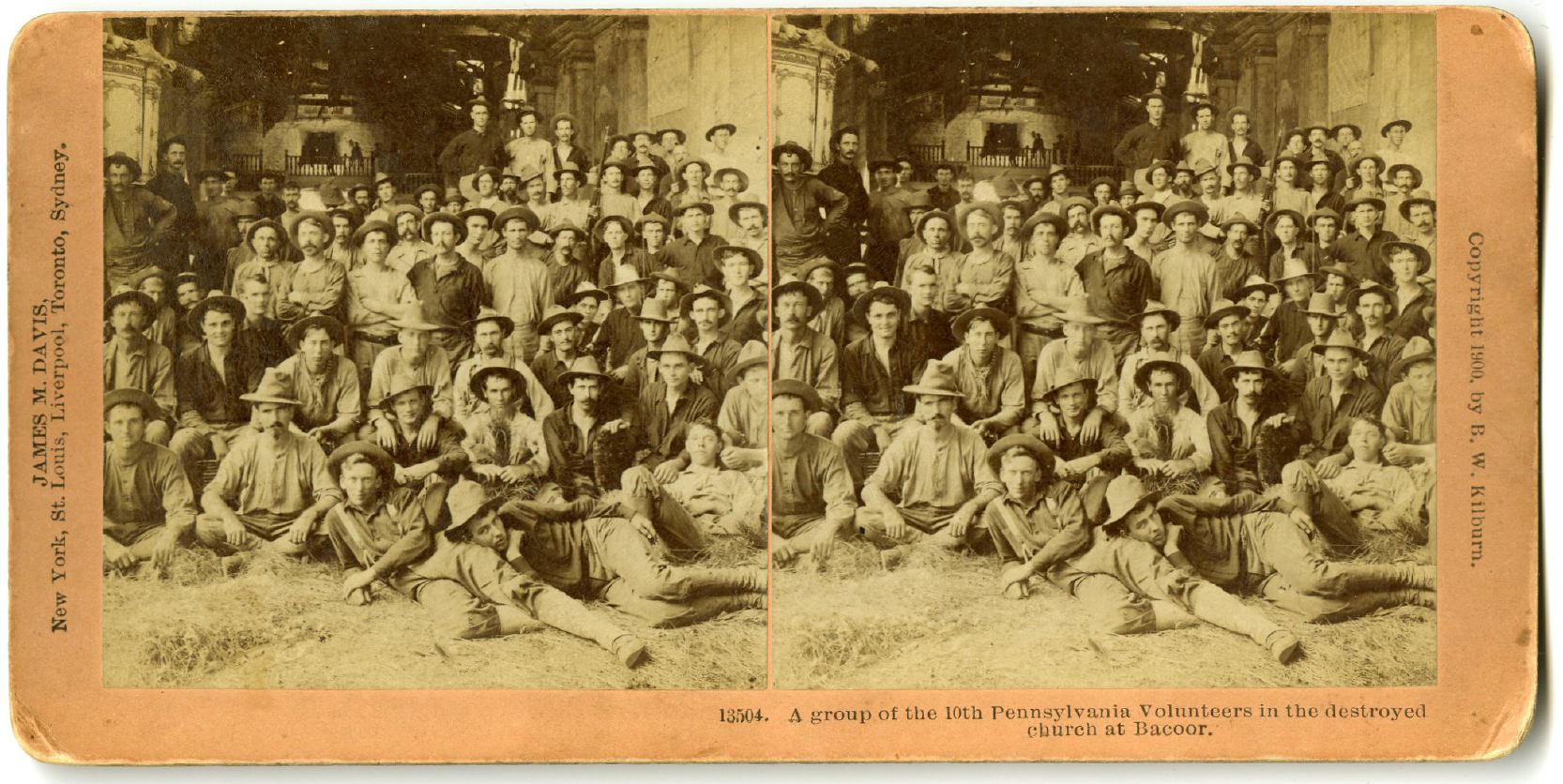

American Soldiers

Photographs of the U.S. forces range from posed groups to battlefield scenes, although high-speed action shots were not yet technologically possible. Such photos show the American soldiers at rest, mixing with Filipinos, poised for battle behind walls and in trenches, and immersed in rural and jungle warfare. They also reveal the mixture of African-American and white U.S. troops who fought in the Philippine-American War, as well as the advanced weaponry (such as artillery and the Gatling machine gun) that accounted for the huge discrepancy between deaths on the American and opposing sides.

|

|

|

| |

Original caption on stereograph: “A group of the 10th Pennsylvania Volunteers in the destroyed church at Bacoor,”

Stereograph published in 1900 by B. W. Kilburn.

Source: Antique Photographics [view]

[ph103_1900_kilburn002]

|

|

| |

Original caption on stereograph: “‘Quanto Valo’ scene in camp of the 10th Infantry, P.I.”

1900 stereograph published by B. W. Kilburn

Source: Antique Photographics [view]

[ph106_1900_kilburn016]

|

|

| |

Original caption on stereograph: “Expecting a Filipino Attack behind the Cemetery Wall, Pasig, Phil. Is’ds,” stereograph, 1899.

Source: Library of Congress [view]

[ph029_1899_LOC_3c36147u]

|

|

| |

Photo caption: “Taking it easy during a lull, 20th KS”

Soldiers of the 20th Kansas Infantry during the

Philippine-American War, ca. 1899

Source: Library of Congress [view]

[ph224_1899_3a16807u]

|

|

| |

U.S. soldiers during the Philippine-American War, ca. 1899

Source: Library of Congress [view]

[ph223_1899_3a02720u]

|

|

| |

U.S. soldiers ford a river during the Philippine-American War, ca. 1899

Source: Library of Congress [view]

[ph225_1899_3a02721u]

|

|

| |

Caption with source: “Black and white U.S. troops with Signal Corps flag,” 1899-1902

Source: Library of Congress and

University of Wisconsin-Madison Libraries [view]

& University of Wisconsin

[ph222_1899-1902_SignalCorps_UWisc]

|

|

| |

Caption with source: “American soldiers with mobile Gatling gun,” 1899

Source: University of Wisconsin [view]

University of Wisconsin

[ph228_1899]

|

|

| |

General Arthur MacArthur and General Elwell Stephen Otis (center left and right) with other U.S. officers, ca. 1900.

Source: Library of Congress [view]

[ph229_1899_3a02725u]

|

|

| |

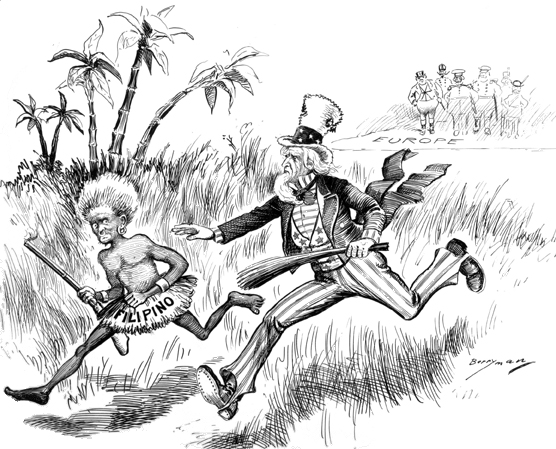

Aguinaldo and the “Philippine Insurrection”

The U.S. public was bitterly divided over the American conquest of the

Philippines. While “anti-imperialist” critics denounced the invasion, supporters of the war defended it in terms of America’s destiny to spread civilization and progress to backward peoples and nations. In the rhetoric of the pro-war camp, the independence movement led by Emilio Aguinaldo, which began against Spain and was redirected against the American invaders after Spain’s defeat, was commonly referred to as an “insurrection.”

The prevailing pejorative view of Aguinaldo and the “insurrection” of his Filipino supporters came through strongly in the political cartoons that emanated from the pro-war camp, as seen in the following two graphics by the famous American cartoonist Clifford Berryman. Aguinaldo’s opposition was ridiculed as puny and pretentious when set against America’s irresistible advance. Filipinos engaged in the resistance were routinely depicted in racist terms as dark-skinned and primitive. This latter imagery was commonplace in contemporary American cartoon renderings of peoples of color in general, whether African Americans in the United States or the native peoples of Mexico, the Caribbean, or Latin America.

|

|

| |

Cartoon Politics

Political cartoons by the prolific artist Clifford Berryman—who continued to produce commentary through World War II—appeared in the Washington Post during the war. The cartoons reflect the racial and cultural condescension, as well as great-power arrogance, that permeated much of the pro-war camp in the American press.

|

|

| |

Clifford Berryman’s cartoon depicts Aguinaldo’s futile attempt to oust the U.S. from the Philippines.

The sign in the background reads:

“Notice. The U.S. is requested to withdraw P.D.Q. (signed) Aguinaldo.”

Source: National Archives

[ph015_1899_2-4-O-067_46_Berryman]

|

|

|

| |

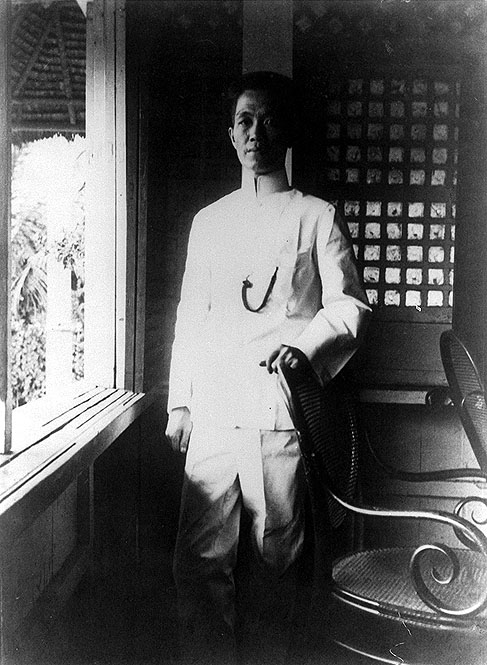

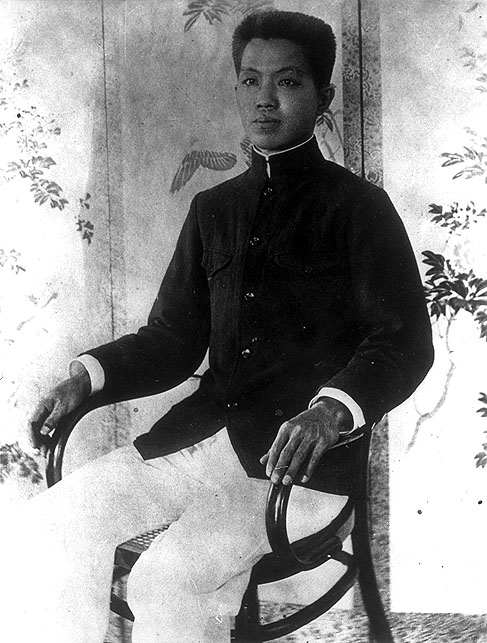

The Americans also used the camera to document their enemies, breaking new ground for the use of photography in counterinsurgency that would be repeated over the course of the 20th century. After the outbreak of the Filipino resistance in February 1899, and particularly after Aguinaldo’s decision in the fall of 1899 to abandon uniforms and battle formations and adopt guerrilla war tactics, American military officials rapidly grew frustrated by the difficulty of knowing whom they were fighting against.

Photo portraits of Aguinaldo himself that appeared during the U.S. conquest commonly conveyed the thirty-year-old’s youthfulness and charisma. His loosely organized forces occasionally posed for the camera or were photographed preparing for battle, but more often entered the photographic record as “insurgent prisoners.”

|

|

|

Two portraits of Emilio Aguinaldo, the charismatic and youthful Filipino independence leader, 1899-1901.

left: National Archives

[view]

right: University of Wisconsin

[view]

[ph013_1899-1901_UWisc] [ph101_1900_UWisc]

|

| |

Caption with source: “Philippine insurgents were mostly from the Tagalo [sic] race which inhabited northern Luzon,” P. Fremont Rockett,

Our Boys in the Philippines: A Pictorial History of the War (1899).

Source: University of Wisconsin

[ph043_1899_UWisc]

|

|

| |

Caption with source: “Philippine insurgent troops in the suburbs of Manila,” from Francis Davis Millett, The Expedition to the Philippines (1899).

Source: Library of Congress Photo Gallery of Philippine Insurgents [view]

[ph206_insurmn1_insurgents_millet]

|

|

| |

The caption published with this photograph reads: “Insurgent Troops in the Trenches. (From a Photograph taken during an Action, by an English Telegraph Clerk.),” from Francis Davis Millett, The Expedition to the Philippines (1899).

Source: Library of Congress

[view]

[ph113_1900c_InsurgTrps]

|

|

| |

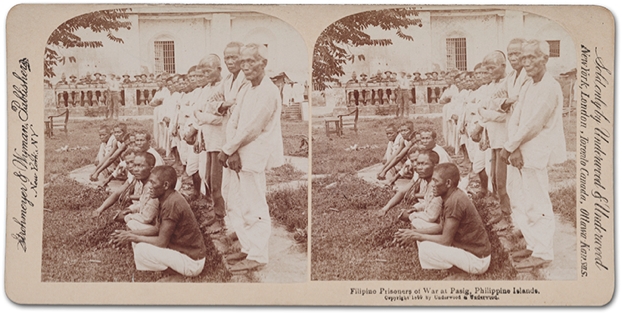

Captured & Imprisoned Insurgents

By officially labeling the war the “Philippine Insurrection,” the Americans turned the struggle for national independence led by Aguinaldo into a criminal rebellion against U.S. authority. “Insurrection” was a legal term that freed U.S. troops from following the laws of war that had emerged at the turn of the century. The word was also a public relations move meant to convince Americans that they weren’t really fighting a war of imperial conquest but were suppressing banditry and bringing law and order to a faraway uncivilized place. But with the vocabulary of crime came its imagery, reactions in the mind’s eye that summoned ideas of criminology and brought its photographic practices from the streets and jails of New York and Chicago to the alleys of Manila and the jungles of Luzon.

Arrested by military police or the rapidly expanding municipal force of Manila, supporters of Philippine independence were photographed, and their photographs were filed away for future reference. The detective branch of Manila’s police filed “about 3,000 photographs of convicted criminals of all classes and nationalities.” Some were hardened criminals; others were captured in citywide sweeps or convicted of political crimes that ranged from staging nationalist theatrical productions to displaying the banned Philippine flag. [1]

|

|

|

| |

Original caption on stereograph: “Filipino Prisoners of War at Pasig, Philippine Islands,” stereograph, 1899.

Source: Library of Congress

[view]

[ph001_00353u]

|

|

| |

Captured Filipinos at Pasay and Paranaque, Manila, 1899

Source: University of Wisconsin [view]

University of Wisconsin [ph047_1899_UWisc]

|

|

| |

Caption with source: “Insurgent prisoners on their way to Manila, under guard: near Polo, Bulacan province – 1899” (with detail below)

Source: University of Michigan Library, Philippine Photographs Digital Archive [view]

Courtesy the Museum of Anthropology, University of Michigan

[ph231_1899_phla333SID]

|

|

| |

With the accelerating imprisonment of captured insurgents, the snapshot and the mug shot soon overlapped. U.S. military officials displaced the Spanish empire in the Philippines but adopted many of their institutions, not least their prisons. Visual surveillance and political repression reached their apogee at Bilibid, a massive prison just outside downtown Manila. Established by the Spanish in 1865, the prison had earned a reputation as a terrifying site of confinement and punishment long before the Americans arrived. With war redefined as crime, the photography techniques recently developed in America for prisoners found new uses to document captured Filipino soldiers.

|

|

| |

Original caption on stereograph: “Officers of the Insurgent Army, Prisoners in Postigo Prison, Manila, Philippine Islands,” stereograph, 1901. (detail)

Source: Library of Congress

[view]

[ph120_1901c_LOC_3c37901u]

|

|

| |

Group of prisoners posed in a courtyard,

from The Philippines through a Camera by George C. Dotter (1899).

Source: Library of Congress

[view]

[ph018_1899_3c21607u]

|

|

| |

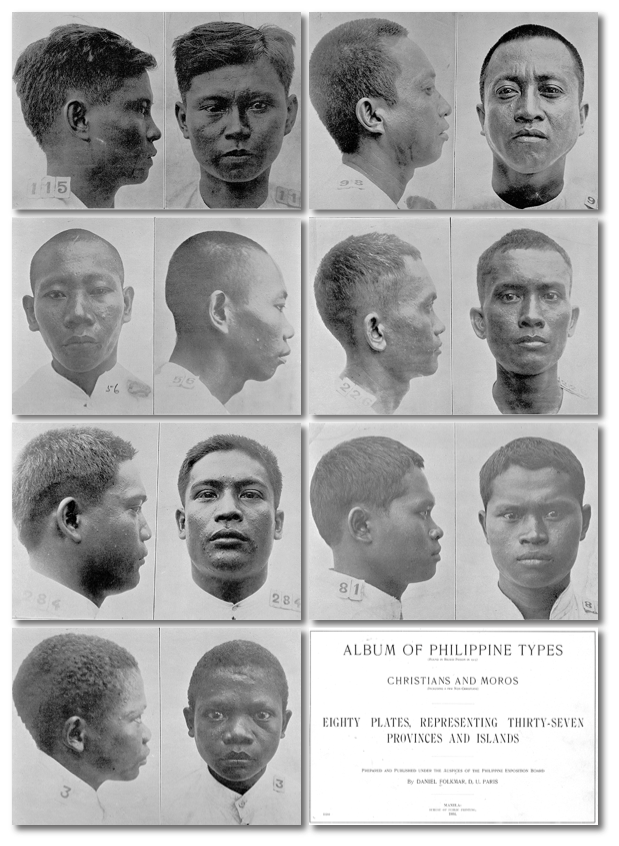

Bilibid Prison

Bilibid was a nexus in the relationship between photography and power: thousands of photographs of Bilibid prisoners filled the archives of the U.S. military as they kept watch on Filipino revolutionaries. Documenting Filipino prisoners also gave American officials the opportunity to study them. In the United States, the emerging science of criminology used photography to document the physical features of the “criminal element”; at the same time, anthropologists were using bodily measurements to classify so-called “primitive” societies.

|

|

| |

Bilibid Prison, from William Dickson Boyce, The Philippine Islands (1899).

[ph232_1899_bilibid_prison_Boyce]

|

|

| |

1899 photo of prisoners in Bilibid Prison by G. C. Doher.

Source: Library of Congress [view]

[ph041_1899_UWisc]

|

|

| |

Daniel Folkmar, a lieutenant governor in the colonial bureaucracy and a self-educated anthropologist, began systematically photographing Bilibid prisoners almost as soon as he arrived in the Philippines in 1903. As the repression of the Philippine independence movement reached nearly every corner of the Philippines, Folkmar saw an opportunity to document the ethnic diversity of Bilibid’s prisoners. In 1903, using the front and side views that were common both in ethnographic photography and the criminal mug shot, Folkmar photographed every one of Bilibid’s 3000 inmates—carefully framing the men’s distance from the camera lens to allow for precise comparison—then recorded their birthplaces and measured their bodies. More than 1000 of the photographs made their way into an exhibit at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair; a smaller group found publication in an Album of Philippine Types.

Published in 1904, the images in Folkmar’s album are both criminal mug shots and anthropological studies, and they show that unequal power relations were the foundation for the photographic practices that scrutinized prisoners and primitives alike. At Bilibid, one exercise of power amplified the other.

|

|

|

| |

Mug shots of Bilibid Prison inmates from

Album of Philippine Types

(found in Bilibid Prison in 1903) Christians and Moros

by Daniel Folkmar, 1904.

Source: University of Michigan [View full album online]

[ph124 – ph132]

|

|

| |

Dead Insurgents

Finally, the Americans also used cameras to document the enemy’s destruction. Whether taken for official military records or as souvenirs, images of battle deaths proliferated from the very beginning of the war. Such images typically showed a battle scene strewn with dead bodies, captioned in popular publications with a cautionary tale of the nefarious Filipino “insurrectionists” who had just come to their ends at American hands: “Insurgents Dead as They Fall,” read the caption of an 1899 photograph. Others boasted that the corpses depicted were the “Work of the Kansas Boys” or “Work of Minnesota Men.” [2] Some were taken for military purposes by Army photographers; others were snapped by a handful of photojournalists who reached the front lines.

Most of the images of battlefield fatalities that were circulated depicted Filipino

forces. The vastly greater number of Filipino noncombatants who were killed do not appear, and photos of dead American soldiers were extremely rare.

|

|

|

| |

Caption with source: “Dead Filipino Soldiers Lie Where They Fell,” 1899.

Source: Library of Congress

[view]

University of Wisconsin [view]

& University of Wisconsin

[ph233_1899]

|

|

| |

Printed caption: “War is Hell: And there is no denying it. These men, though our self constituted enemies, had loved ones, mothers, sweethearts and wives, who will wait long but in vain for their homecoming. They demonstrate the effectiveness of the American volley firing.”

Page from Souvenir of the 8th Army Corps, Philippine Expedition. A Pictorial History of the Philippine Campaign, 1899.

[view complete album online]

[ph082_1899_neely_Souv8thArmy_0115]

|

|

|