| |

The “people of the five nations” brought a babel of different languages to Yokohama that, as can be easily imagined, caused a great deal of confusion. Prior to Perry’s visit, the only European language the Japanese had slight familiarity with was Dutch, which a few officials had picked up through contact with the small Dutch contingent in Nagasaki. In his negotiations with the Japanese, Perry relied on a Dutch interpreter as well as an American missionary versed in reading Chinese and thus capable of recognizing the ideographs that written Japanese and Chinese shared. Townsend Harris commonly relied on the young and ill-fated Dutchman Henry Heusken as a translator.

In Yokohama, verbal communication between Japanese and foreigners was initially carried out in what a British observer in 1862 called “a sort of bastard language” in which Japanese and foreign words were jumbled haphazardly together—all accompanied by gestures and sign language. Where written exchanges were involved, the foreign merchants relied heavily on their Chinese assistants. It was not until 1867 that the American missionary and physician James Hepburn, a Yokohama resident, published the first Japanese-English dictionary. Hepburn devised the system for “romanizing” Japanese—that is, rendering it in Latin letters—that became known as romaji in Japanese.

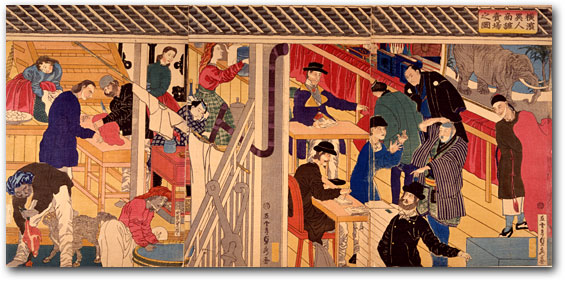

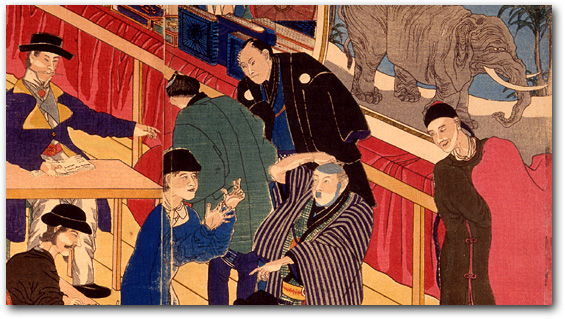

Sadahide captured the liveliness and body language of these complicated communications, and considerably more, in a work titled “Picture of a Salesroom in a Foreign Mercantile Firm in Yokohama.”

|

“Picture of a Salesroom in a Foreign Mercantile Firm in Yokohama”

by Sadahide, 1861 (detail below)

[Y0086] Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

|

One side of this print amounts to a backroom scene of the foreigners’ servants engaged in tasks such as preparing food and doing laundry. One of the servants is identified as a “black laundress.” A turbaned Indian stands beside her plucking a duck. On the other side of this engaging print, Caucasian, Japanese, and Chinese men are absorbed in an animated exchange. Embossed account books and a startling picture of an elephant rest on a shelf behind them.

|

|

Even more numerous than prints of the foreigners at work were depictions of them at home or at play. In their renderings of residences and domestic family scenes, the Yokohama artists let their imaginations stray particularly far from reality. Not only was the number of actual families very small, but the life-style of males who did take up residence was usually less sumptuous—and more typical of bachelor life—than what the prints conveyed. Most of these men lived in or above their offices or warehouses, and early Japanese-language directories for the foreign settlement tended to identify the master (danna-san) of each “lot” or house number, along with his principal employees, servants (kozukai), groom or stableman (bettō), and mistress (musume—literally “daughter,” but used at the time as argot for a young Japanese woman). In a study of one such directory dating from 1861–1862, the Australian student of the foreign settlements Harold Williams identified “79 danna-sans, against which were listed by name 30 musume, 79 kozukai, and 52 bettō.”

A woodblock by Yoshikazu titled “Foreigners Enjoying a Banquet” offers an unusually sharp illustration of the extent to which artists ignored such mundane realities and used “Yokohama” simply as a vehicle for introducing ordinary Japanese to the customs and appearance of foreigners in their native lands. Published in December 1860, the print depicts a small girl dancing with castanets in the midst of a rather stiff group of Caucasian men, women, and children. Ships in the harbor and the exterior of a Japanese-style building are visible through an open window.

|

![“Picture of Foreigners Enjoying a Banquet” by Yoshikazu, December 1860 [Y0142] Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution](image/Y0142_MayFest_Party_s.jpg)

“Picture of Foreigners Enjoying a Banquet” by Yoshikazu, December 1860

[Y0142] Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

|

In fact, the model for this scene was an engraving that appeared six months earlier in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, accompanying an article about a children’s dance held in Washington in honor of the Japanese officials who had come to exchange ratifications of the Harris Treaty. Yoshikazu simply excised the Japanese figures in the original graphic, replaced them with his own version of Americans, and cut a window in the wall to bring in Yokohama.

|

![Children dance at the “May Festival Ball” given in honor of the Japanese ambassadors. Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper June 6, 1860 [YFLIN0606]](image/YFLIN0606_dance.jpg) |

Children dance at the

“May Festival Ball” given in honor of the Japanese ambassadors.

[YFLIN0606] Frank Leslie’s

Illustrated Newspaper,

June 6, 1860

|

In a more charming but equally implausible depiction of the Westerners at play in the foreign settlement, Yoshikazu moved directly into the interior of a merchant’s private residence. This particular domestic scene actually carries a title calling the residence a yashiki—usually used to refer to a daimyō’s mansion. Yoshikazu’s rendering manages to include harbor, mirror, chandelier, carpet, glass windows, dining-room table laden with food and drink, people seated on chairs, kitchen with a wood-burning stove, and well over a dozen men, women, and children—including a man playing a cello and another getting a shave.

|

![“Picture of a Foreign Residence in Yokohama” by Yoshikazu, 1861 [Y0099] Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution](image/Y0099_Residence_s.jpg)

“Picture of a Foreign Residence in Yokohama” by Yoshikazu, 1861

[Y0099] Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

|

These depictions of married couples and mixed gatherings of men and women reveal obvious fascination not merely with “family” (a familiar Japanese preoccupation), but more particularly with Western women. We know from the diaries and journals of members of the 1860 Japanese mission to the United States that the Japanese were shocked (and, in some cases, attracted) by the dress and behavior of American women, and by relations between men and women more generally. The deference generally shown to women was deemed (as one high official wrote) “a most curious custom,” and their inclusion in banquets and public ceremonies caught the Japanese completely by surprise. That a man should stand while a woman sat, or walk hand in hand with his wife in public, or bring a glass of water or wine to her was simply astonishing—to say nothing of ballroom dancing, which made it into one journal as “this extraordinary sight of men and bare-shouldered women hopping about the floor, arm in arm.”

While the bare shoulders rarely made it into the Yokohama prints, the elegantly dressed Caucasian woman with her corseted waist and extraordinary full-skirted crinoline gown was an irresistible subject for the woodblock artists. Indeed, like other pictorial conventions that crept into the “Yokohama prints”—the gold-flecked clouds, majestic Mount Fuji, filigreed splash of water, daimyō-like processions of foreigners, blown-away-roof perspective, dramatic sense of urban hustle-bustle in general—“pictures of beauties” (bijinga) were well established in the popular culture. (Neither bosom, waist, nor derriere were part of the Japanese canon of feminine beauty, however.) Usually these beauties were women of the pleasure quarters, but the subject might be a shop girl or merchant wife as well.

In the portrait prints of “people of the five nations,” the Yokohama artists were essentially adapting and coloring the “fashion plates” that routinely appeared in illustrated foreign publications. In their more congested and animated depictions of the foreigners at play, however, they often went beyond this and brought Japanese and Western beauties together in the same composition. As usual, Sadahide did this with surpassing skill. In a well-known print that can be seen as the “upstairs” counterpart to his “downstairs” depiction of merchants doing business and servants tending to menial tasks, he imagined a lively mixed party on the open verandah of “a mercantile establishment in Yokohama.”

|

![“Picture of a Mercantile Establishment in Yokohama” by Sadahide, 1861 [Y0141] Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution](image/Y0141_AmericanParty_s.jpg)

“Picture of a Mercantile Establishment in Yokohama”

by Sadahide, 1861 (details below)

[Y0141] Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

|

All kinds of exotica—Japanese and Western alike—have been gathered here. Red and white stripes of an American flag flutter in the top corner. Trading vessels anchored in the harbor occupy the background. A lavish Western-style dinner party takes place in a back room, under an elaborate chandelier.

![“Picture of a Mercantile Establishment in Yokohama” by Sadahide, 1861 [Y0141] Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution](image/Y0141_AmericanParty_music.jpg) Paintings on the walls include both Mount Fuji and men riding camels. And a cosmopolitan group holds center stage. An elegant geisha observes one of her courtesan colleagues playing a samisen, while a Caucasian beauty holds and strums a viola in the same manner (Sadahide obviously had never seen how Western stringed instruments were actually played). Paintings on the walls include both Mount Fuji and men riding camels. And a cosmopolitan group holds center stage. An elegant geisha observes one of her courtesan colleagues playing a samisen, while a Caucasian beauty holds and strums a viola in the same manner (Sadahide obviously had never seen how Western stringed instruments were actually played).

|

![“Picture of a Mercantile Establishment in Yokohama” by Sadahide, 1861 [Y0141] Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution](image/Y0141_AmericanParty_queue.jpg) Elsewhere on the verandah, a white man dressed in his holiday finest observes an American boy tugging the queue of a Chinese servant, while another Japanese beauty looks on. In the back room, far removed from all this, a second Chinese, clearly of higher status, converses with a Westerner. Elsewhere on the verandah, a white man dressed in his holiday finest observes an American boy tugging the queue of a Chinese servant, while another Japanese beauty looks on. In the back room, far removed from all this, a second Chinese, clearly of higher status, converses with a Westerner. |

Many of the prints depicting entertainment move the foreigners into a pure Japanese milieu, usually involving the Miyozaki entertainment quarters, where a special establishment (named Gankirō) was reserved for foreign patrons. The same Yoshikazu who managed to get cello playing, shaving, wood-burning stoves, and the harbor into a single print also produced a comparably busy “Picture of Foreigners’ Revelry at the Gankirō in the Miyozaki Quarter of Yokohama.”

|

![“Picture of Foreigners' Revelry at the Gankirō in the Miyozaki Quarter of Yokohama” by Yoshikazu, 1861 [Y0148] Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution](image/Y0148_FanRoom_wide_s.jpg)

“Picture of Foreigners' Revelry at the Gankirō in the Miyozaki Quarter of Yokohama”

by Yoshikazu, 1861 (details below)

[Y0148] Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

|

The center of attention is a group of foreign men enjoying a drinking party in the company of female Japanese entertainers, including two geisha playing samisen. Just as Japanese males would do in the same setting, they sit on the floor, pampered and animated. One has taken his coat off and is doing an impromptu dance. It is easy to imagine them tipsy.

|

![“Picture of Foreigners' Revelry at the Gankirō in the Miyozaki Quarter of Yokohama” by Yoshikazu, 1861 (details below) [Y0148] Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution](image/Y0148_FanRoom_sake.jpg) |

Barely visible in the upper righthand corner, foreigners enjoy a Western-style dinner. To their left is one of the Gankirō’s most famous attractions, known as the Fan Room from the decorations on its sliding doors.

|

![“Picture of Foreigners' Revelry at the Gankirō in the Miyozaki Quarter of Yokohama” by Yoshikazu, 1861 (details below) [Y0148] Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution](image/Y0148_FanRoom_dinner.jpg) |

A Yokohama print by another artist, Yoshiiku, actually enters the Fan Room to reveal an unexpected five-nations-plus scene in which the male and female participants—apart from two high-ranking geisha (oiran) and two little Japanese boys affiliated with the Gankirō—carry explicit national labels. They represent, Yoshiiku tells us, an English man and woman, Russian man and woman, American man and woman, Frenchman, and Dutchman (identified as “Red Hair,” a familiar old term attached to the Dutch in Nagasaki). The dancing figure holding center stage is a well-dressed Chinese (called “Nanjing” in the label).

|

![“Picture of Foreigners of the Five Nations Carousing in the Gankirō” by Yoshiiku, 1860 [Y0149] Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution](image/Y0149_FanRoom_closeup_12550.jpg)

“Picture of Foreigners of the Five Nations Carousing in the Gankirō” by Yoshiiku, 1860

[Y0149] Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

|

Imaginary as so much of this may have been, this picture-world of “Yokohama” reflected an animated sense of intermingling rarely found in the cooler and more detached Western illustrations of Japan and the Japanese. While violently anti-Bakufu samurai were clamoring to “expel the barbarians,” the Yokohama artists and their large domestic audience found the foreigners curious, to be sure, but also accessible and even attractive. The very notion of “people of the five nations” introduced to a secluded feudal society not merely the unfamiliar concept of the modern nation-state, but also the spectacle of peoples of different races and cultures interacting as equals—a little showpiece, as it were, of internationalism.

Such generally positive impressions were easily accommodated in the tolerant, affirmative, urbane world of woodblock-print imagery. As Foster Rhea Dulles put it, the Yokohama boomtown “was a little oasis relatively free from violence and providing a showplace of Western civilization.”

The most obvious Western counterpart to the outpouring of Yokohama prints that greeted the opening of the port in 1859 was to be seen in American coverage of the Bakufu’s 1860 mission to the United States. Here, too, the “foreigners” were a sensation. Enthusiastic crowds turned out to see them in every city they visited, and the media was almost unanimous in praising their dignity and decorum. At one point, Harper’s Weekly went so far as to comment that “civilized as we boast of being, we can learn much of the Japanese.” Still, in Western eyes they invariably remained a people apart—archaically costumed and, with but a few exceptions within the large visiting delegation, reticent and reserved. Social interaction took place entirely at a formal level. There was little sense of private lives.

The Yokohama prints, by contrast, celebrated fraternization and even outright sexuality as natural. The entertainment district was, of course, a favorite setting for woodblock artists in general. Now they let the foreigners in, and artists like Yoshitora did not hesitate to go further to depict those erotic encounters between Western men and Japanese women that drove the Western clergymen and other moralists to distraction.

His romantic rendering of a bearded foreigner gazing at the moon with a courtesan in the Miyozaki pleasure quarter captured the more expensive end of such liaisons. In another print, titled “An American Drinking and Carousing,” Yoshitora’s mixed couple strikes a scarcely disguised phallic pose together.

|

![“Autumn Moon at Miyozaki”

by Yoshitora, 1861 [Y0122] Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution “American Drinking and Carousing” by Yoshitora, 1861 [Y0145] Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution](image/Y0122_Y0145_ce15576.jpg) |

“Autumn Moon at Miyozaki”

by Yoshitora, 1861

[Y0122] Arthur M. Sackler Gallery,

Smithsonian Institution |

“American Drinking and Carousing”

by Yoshitora, 1861

[Y0145] Arthur M. Sackler Gallery,

Smithsonian Institution

|

While Western photographers and illustrators of this early period also found the geisha or courtesan or lowly prostitute an enticing subject, they took care to avoid such open suggestion of interracial intimacy. “Madame Chrysantheme” and “Madame Butterfly” would come decades later.

While the woodblock artists obviously found the people of the five nations fascinating, it was just as natural for them to depict foreigners finding the Japanese fascinating as well. One of Yoshitora’s most chaotic prints, for example, amounted to a jumble of “Yokohama” subjects he had treated individually elsewhere. As piled together here, the “amusements” of the foreigners included not only riding on horses or in horse-drawn carriages, or purchasing Japanese goods, but also partying in the Miyozaki (drinking sake and listening to the samisen) and attending a Kabuki performance.

|

![“Picture of Amusements of Foreigners in Yokohama in Bushū “ by Yoshitora, 1861 [Y0144] Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution](image/Y0144_Amusements_551.jpg)

“Picture of Amusements of Foreigners in Yokohama in Bushū” by Yoshitora, 1861

[Y0144] Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

|

In another scene from the entertainment quarter, Yoshitora’s colleague Yoshikazu offered a highly original rendering of a dance performed by young girls for the merchants and their wives. In this composition, the scene is depicted from backstage. It is the Japanese performers who are of central interest, the foreigners but their appreciative audience.

|

“Picture of a Children's Dance Performance at the Gankirō in Yokohama” by Yoshikazu, 1861

(detail) [Y0146]

Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

|

![“Picture of a Children's Dance Performance at the Gankirō in Yokohama” by Yoshikazu, 1861 (detail) [Y0146] Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution](image/Y0146_dance_frombook_det_s.jpg)

|

|

|