| |

“Yokohama prints” (variously known in Japanese as Yokohama-e, Yokohama ukiyoe, and Yokohama nishikie) comprise a small and distinctive subset within the great tradition of woodblock artistry that had flourished since the mastery of color-printing techniques in the 1760s, almost exactly a century before the opening of the treaty ports. They were especially popular in the few years immediately following the arrival of the Western merchants and traders. According to one estimate, between 1859 and 1862 some 31 artists produced over 500 different “Yokohama” images, involving more than 50 different publishers in the process, most of them located in Edo. The total print run in this great early burst of interest and energy may have been as high as 250,000 copies. The Yokohama prints are as excellent a source as one can find for gaining insight into the “first impressions” of the foreigners that were made available to ordinary Japanese.

|

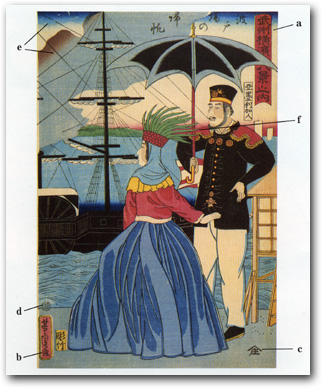

“Eight Views of Yokohama: Sails Returning

to the Landing Pier” by Yoshitora, 1861

[Y0119] Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

|

Looking at Woodblock Prints

Japanese prints of the 19th century usually have a title block (a), the artist’s signature and artistic name (b), and a publisher’s seal (c). A censor’s mark (d), which indicates that the official government censor had deemed the print acceptable for sale, may also be found.

Gradation of color that resembles watercolor painting (e) is common in Yokohama prints. Precise registration of fine lines and color areas (f) is also characteristic of the best prints, but alignment may be slightly askew on prints that were carelessly produced.

|

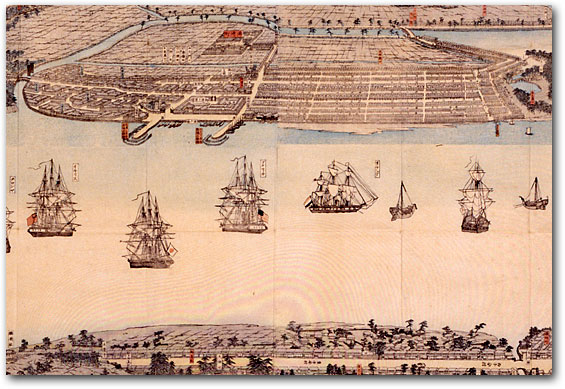

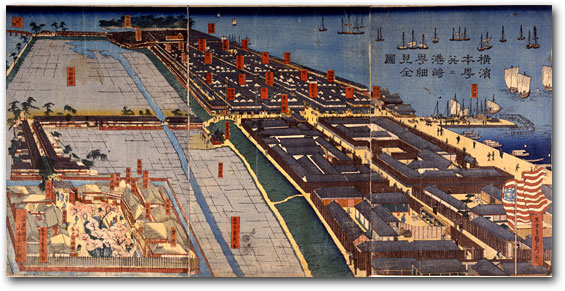

A few artists, led by the brilliant Sadahide (born in 1807), brought exceptional talent and imagination to this enterprise. His panoramic “Complete Picture of the Newly Opened Port of Yokohama” (seen above)—pieced together from eight oversize sheets of paper—is one of the largest composite prints ever issued in Japan. Published shortly after the port opened, it literally served as a map of the entire area. One sees here not merely the foreign settlement and two piers that the Bakufu had built, but also the adjoining Japanese district, the open fields beyond, and—an entirely separate enclave—the entertainment quarters that catered to foreigners as well as Japanese. The entire new city was surrounded by water—harbor in front and canals at the side and back—thus enabling the Bakufu to monitor the movement of people in and out. The artist’s vantage-point was a village near Kanagawa on the opposite shore. The Tōkaidō highway that the Bakufu worried about runs along the bottom of the print.

|

“Complete Picture of the Newly Opened Port of Yokohama” by Sadahide, 1859-60 (detail)

[Y0044] Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

|

In other overviews of the layout of Yokohama, Sadahide offered a closer picture of how thoroughly the Bakufu had prepared the site for the foreigners’ arrival. The angle-of-vision adopted in these prints followed a traditional aesthetic convention known as fukinuki yatai—literally, blowing off the roof—offering an angled bird’s-eye view of the scene.

The number of foreigners who took up residence in the first year probably numbered only a hundred or so, rising to around 250 by mid 1861 (of whom 64 were Americans) and to some 400 by 1866. The British accounted for around 80 percent of foreign trade up to the Meiji Restoration, and always comprised the single largest national contingent. Despite these modest initial numbers, as Sadahide’s prints reveal, the new city had the look of a substantial planned community from the very beginning. The warehouses and residences of the foreign compound lay to the east, behind walls; alongside this compound, to the west, were the smaller buildings of the larger Japanese commercial district. A road separating the two settlements led through open fields to the Miyozaki entertainment quarter, also enclosed behind walls and, additionally, a small moat.

|

"Complete Detailed View of Yokohama Honchō and the Miyozaki Quarter"

by Sadahide, 1860

[Y0054] Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

|

From an entirely different angle-of-vision, Sadahide also turned passing attention to “Honchō-dōri,” the broad main avenue in the new Japanese commercial quarter. Here—now drawing on European principles of perspective that were occasionally copied in traditional woodblock prints (the secluded Japanese encountered “perspective pictures” through the Dutch)—he succeeded in capturing the commercial dynamism of the late feudal era. By withdrawing into seclusion, Japan had failed to experience the scientific and industrial revolutions that propelled the West to new levels of wealth and power. This material backwardness was what made the demands of the “five nations” irresistible. At the same time, however, Japan had undergone an impressive commercial revolution, accompanied by great urban growth and widespread literacy. As a result, the country was better prepared to engage the West than the foreigners yet realized. Sadahide’s “Honchō-dōri” can be seen as a microcosm of this indigenous economic vitality.

|

“Picture of Newly Opened Port of Yokohama in Kanagawa” by Sadahide, 1860

Sadahide has portrayed the busy commerce that took place in the main street of

Yokohama’s Japanese business district.

[Y0085] Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

|

Although economic chaos accompanied the opening of the treaty ports (disrupted domestic trade patterns, inflation, the gold drain, enormous expenditures incurred by the Bakufu both in preparing the ports and paying reparations for unpleasant incidents), Yokohama itself quickly emerged as a boomtown. Despite the country’s reluctance to be drawn into the global economy, and despite the fixed tariffs imposed under the unequal treaties, Japan was blessed with two export commodities that enabled it to keep afloat in the rough waters of international trade: raw silk and tea. (Other Japanese exports included marine products, copper, and art objects such as lacquerware, porcelain, and fans. Basic imports from the West included cotton yarn and cloth, woolen fabrics, iron products, sugar, tobacco, clocks and watches, glass, and wines and liquors.) In 1859, the first year of trade, the total value of exports out of Yokohama amounted to $400,000, while imports were valued at $150,000. By 1866, the comparable figures for Yokohama had risen to over $14,000,000 in exports and around $11,400,000 in imports. (The balance shifted beginning in 1867, but tea and silk remained critical exports until the turn of the century.)

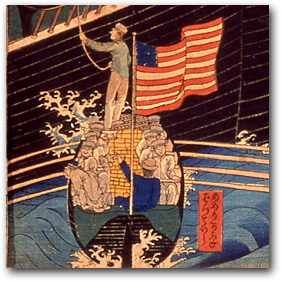

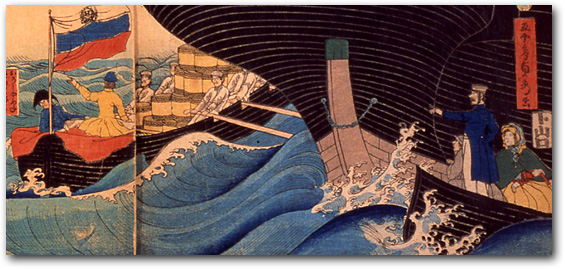

When Commodore Perry’s coal-burning, smoke-belching “black ships” arrived in Edo Bay, they had inspired a variety of Japanese prints and paintings. These ranged from cartoon-like monster ships to realistic renderings of an almost diagramatic nature, almost always depicting the American vessels in perfect profile. With the opening of the treaty ports five years later, great numbers of foreign merchant ships suddenly descended on Japan, operating under both steam and sail—opening up a whole new seafaring world for artists to capture for their curious countrymen in the interior.

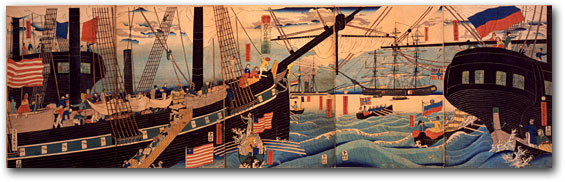

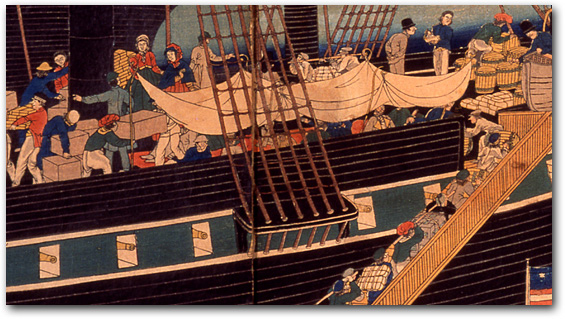

Again, it is Sadahide who has left us the single most dramatic impression of the unprecedented bustle in Yokohama harbor. In a masterful print titled “Picture of Western Traders at Yokohama Transporting Merchandise”—made by joining five standard-size wood blocks (for a total width of 50 inches)—Sadahide contrived to introduce almost everything associated with the new era of commerce.

|

“Pictures of Western Traders at Yokohama Transporting Merchandise” “Pictures of Western Traders at Yokohama Transporting Merchandise”

by Sadahide,1861 (details below)

[Y0064] Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

|

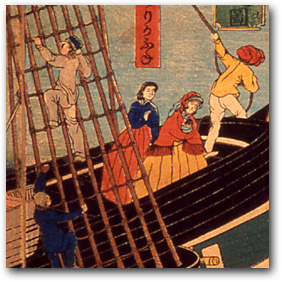

Five vessels, both steamships and sail ships, represent the five nations; their national flags are clearly displayed. Workers of various nationalities carry merchandise onto the boats; clerks make notes; crewmen climb the riggings; foreign women are as conspicuous as their merchant husbands; there are even tantalizing glimpses through large portholes into a luxurious life inside. At the same time, there is a subtle touch of the ominous: a long row of small cannon runs the length of the American ship.

|

|

And there is also a touch of the reassuringly familiar: the rolling waves and elegant splash of whitecaps are pure forms of serene traditional design.

|

|

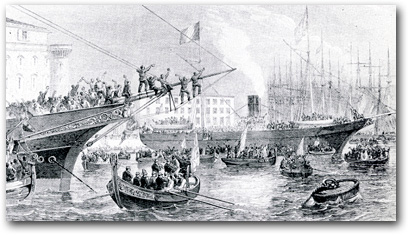

In a charming anecdote, it is said that Sadahide dropped his brush in the water while making preliminary sketches for this print, and had to finish with a pencil borrowed from a foreigner. Certainly no other Yokohama print captures the energy and bustle of the harbor as vividly as this one does. At the same time, however, we can point to a possible model (or inspiration) for the scene in an engraving of a European port scene that appeared in the Illustrated London News five months before Sadahide’s print was published in April 1861. Even more telling where the departure from strict reality is concerned, however, is the large number of foreign women. Although wives and children did join their merchant husbands in Japan in the course of time, their number was miniscule in 1861.

|

|

Harbor scene at Naples. (detail)

[YILN1103]

Illustrated London News, November 3, 1860

|

To Sadahide and his artist colleagues, “Yokohama” was essentially synonymous with “the West”—a window looking out of Japan upon the unknown world of foreign nations that lay across the seas. Thus, it was perfectly appropriate to people it with figures who may not have been literally present. It was in this spirit that they imagined the “people of the five nations” parading all together in a marching band.

|

“Picture of a Sunday in Yokohama” by Sadahide, 1861

(details below)

[Y0132] Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

|

They even had them marching in a single grand procession—much like a favorite subject in traditional woodblock prints, the elaborate retinues of the feudal lords who were constantly traveling to and from the shogun’s capital in Edo. One such processional print by Sadahide, issued in 1861, includes over 150 figures and would have amounted to almost the entire foreign community in Yokohama at the time!

|

“Picture of People of the Five Nations: Walking in Line”

by Sadahide, 1861 (details below)

[Y0130] Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

|

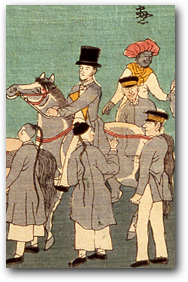

Despite the pervasive cliché of “people of the five nations,” when depicting crowded scenes the Yokohama artists also commonly took care to include two nationalities that accompanied the Westerners but did not count in the great-power or great-nation game—the Chinese and South Asian Indians. Chinese men served the Westerns as both domestic servants and, more significantly, mercantile assistants or compradors. Already accustomed to working with Americans and Europeans in China, they played an invaluable mediating role in Japan, where they were easily identifiable by their distinctive gowns and long braided queues or pigtails. They were of particular use in handling documents, for although the Chinese and Japanese spoken languages bear no resemblance, the written languages share common ideographs. The Indians, commonly male and always distinguished by their turbans and dark complexions, functioned primarily as domestic servants, particularly for the British.

|

Chinese and Indians among the “people of the five nations” |

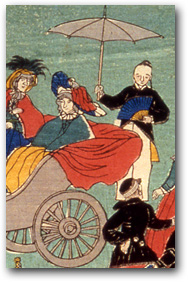

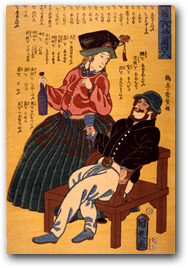

Alongside such crowded scenes, the Yokohama artists also created what amounted to a little portrait gallery of representative foreigners. Here, each print featured just a few figures—frequently a married couple—representing a specific nationality. Sometimes these portrait prints also incorporated a brief glossary of words or phrases from the subjects’ native language. None of these were actual posed portraits. Western magazines provided the copybooks for the fashion statements seen here. Among the Yokohama-print artists, a favorite publication in this regard was once again the Illustrated London News, which ran a monthly graphic devoted to the latest fashions from Paris.

|

![“The Paris fashions for September” [YILN0207] Illustrated London News, September 1, 1860](image/YILN0207_fashion.jpg)

|

“The Paris fashions for September”

[YILN0207]

Illustrated London News,

September 1, 1860

|

Even when presented as national “types,” however, these portraits usually conveyed considerable individual appeal. In one rendering of “the English,” for example, a woman was holding—of all things!—a Yokohama print of two foreigners. |

|

English couple holding a

Yokohama print (detail)

“English Couple”

by Yoshikazu, 1861

[Y0079] Arthur M. Sackler Gallery,

Smithsonian Institution

|

|

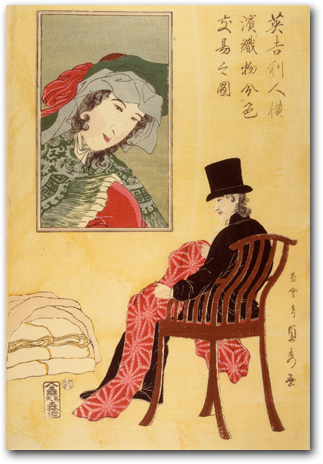

Another rendering of the English depicted a merchant seated by a large framed portrait of his beautiful absent wife. This was a traditional pictorial convention for suggesting both loneliness and affection—enhanced in this instance by the merchant holding in his lap a piece of dyed fabric he presumably had purchased for his spouse. |

"English Man Sorting Fabric

for Trade at Yokohama”

by Sadahide, 1861

[Y0100] Arthur M. Sackler Gallery,

Smithsonian Institution |

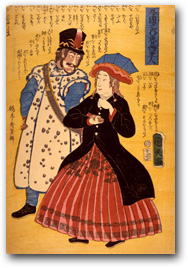

Other portrait prints depicted a Russian couple dressed in warm clothing, obviously reflecting the cold nature of their place of origin; a French couple drinking wine; and a Dutch couple with a telescope.

|

“Among the Five

Nations: Russians” by Kunihisa, 1861

[Y0111] |

“Among the Five

Nations: The French”

by Kunihisa, 1861

[Y0110]

|

“People of the Five

Nations: Holland” by Sadahide, 1861

[Y0113] |

An exceptionally beautiful print by Yoshitora went beyond the conventional “people of the five nations” format to portray two Chinese men under a parasol in the snow. They were returning from the market, carrying a wrapped bottle and package of food. |

|

“Eight Views of Yokohama in

Bushū (Modern Musashi

Province): Snow on the

Morning Market” by

Yoshitora, 1861

[Y0123] Arthur M. Sackler Gallery,

Smithsonian Institution |

|

Representative Americans in the portrait prints often included a woman wearing a feather hat that looked like a pineapple—a bizarre fashion statement that apparently was inspired by a profile on a U.S. coin. |

“Among the Five Nations: Americans” by Kunihisa, 1861

[Y0109] Arthur M. Sackler Gallery,

Smithsonian Institution |

|

Less disconcerting, and certainly more prophetic, was a print by Yoshikazu showing an American woman seated at a Singer sewing machine, while her husband, standing beside her, held up a pocket watch. Inscribed on this print was a long text about “The United States of America” extolling the country’s “large population” and “supreme prosperity and strength.” The text went on to observe that “the people are patriotic and, moreover, quite clever. In the world, they are foremost in science, armaments, and commerce. The women are elegant and beautiful.” |

|

“The United States of North America” by Yoshikazu, 1861

[Y0169] Arthur M. Sackler Gallery,

Smithsonian Institution |

|

Looking at such sympathetic portrayals, it is difficult to imagine the anti-foreign uproar that was roiling the country elsewhere.

“Americans Strolling About”

by Yoshifuji, 1861

[Y0137] Arthur M. Sackler Gallery,

Smithsonian Institution |

|

|