| |

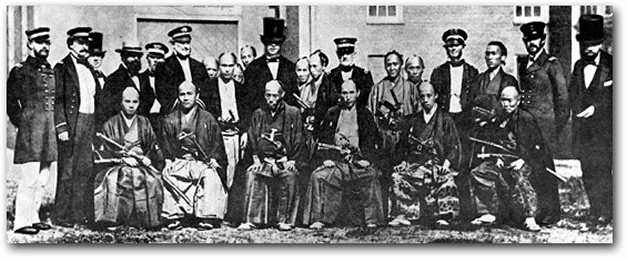

There were other sides to all this tumult, however, that were creative and abounding in good will. In 1860, for example, the Bakufu sent a delegation of 77 officials to the United States to exchange ratifications of the Harris Treaty. This unprecedented mission sailed from Japan on the Powhatan, accompanied by a soon famous Dutch-built steamship flying the Japanese flag and manned by a Japanese crew.

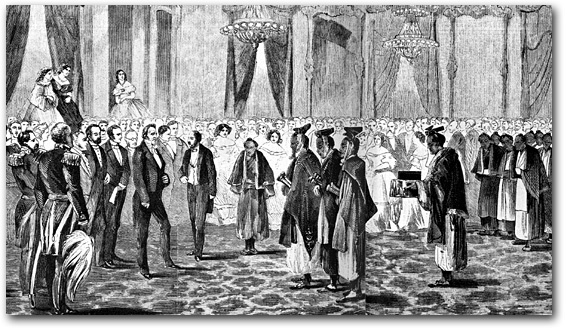

The delegation visited San Francisco, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York as well as Washington, and was greeted with parades and elaborate festivities wherever it went. Philadelphia declared the day of the delegation’s visit a holiday. New York City celebrated the visit with a gigantic ball featuring five orchestras, as well as a parade that attracted an estimated half-million spectators. The great Walt Whitman was moved to compose a poem titled “The Errand-Bearers” in commemoration of the occasion.

|

The 1860 Japanese Mission to the United States. Photograph by Mathew Brady

National Archives

|

Members of the 1860 Japanese mission to exchange ratifications of the Harris Treaty

meeting with President Buchanan at a gala celebration in the White House.

Harper’s Weekly, May 26, 1860

|

Equally constructive—albeit of an entirely different order—were developments in the new treaty ports themselves. And none of these locales was more attractive to the foreigners, or to their merchant counterparts on the Japanese side, than Yokohama.

The five ports recognized under the Harris Treaty were Kanagawa (where Perry had signed his treaty in 1854), Nagasaki, Hakodate, Niigata, and Hyōgo (later renamed Kobe). Of these, the key ports were Kanagawa and Nagasaki. For various reasons, delays impeded the opening and development of the other three.

Instead of building facilities at Kanagawa, however, the Bakufu chose to do so at Yokohama on the opposite shore of the harbor. Their rationale was eminently practical. Kanagawa was situated on the great Tōkaidō highway that linked Edo and Kyoto, and the Bakufu feared that placing foreigners in such close proximity to the samurai retinues that were constantly traveling on the Tōkaidō would be an invitation to mischief and murder. Although the Japanese government proceeded to build quarters for the foreigners at the new location without prior consultation with the five nations, causing consternation among the foreign diplomats, the choice was felicitous and pleased the Western merchants. Yokohama was a better anchorage, and soon became a great one. The fact that it was situated only 17 miles from Edo, which had a population of around a million residents at the time, made Yokohama far and away the most attractive of the new ports.

|

|

Map of Japan, ca. 1860

|

When the Harris Treaty was signed in 1858, Yokohama was a small fishing village surrounded by wetlands and tidal creeks. 10 years later, when the Bakufu was overthrown, it was a teeming city with a population of more than a hundred thousand. Telegraph lines were installed in Yokohama and Tokyo (Edo’s new name) in 1869, and by 1872 the two cities were connected by Japan’s first railway. (The telephone was introduced in 1877.) Yokohama was where “people of the five nations” put in with their great merchant ships, flew their flags, introduced their foods and clothing and languages, displayed (for better or worse) their so-called national characteristics, and operated their trading firms, warehouses, banks, churches, stores, hotels, saloons, and “cow yard.”

While Yokohama was where Japanese bumped up against “the West” most intimately in the early 1860s, however, it also quickly became a dream window. It became a place, that is—or, at least, a place-name—where artists and other Japanese chroniclers of the “people of the five nations” did not hesitate to let their imaginations run wild. Almost everything one could show or tell about Westerners and how they lived was imagined as being present in “Yokohama”—even if it was not really there.

As a result, the picture of Yokohama that Japanese artists presented for Japanese consumption was very different from the picture of Yokohama—or of Japan more generally—that Westerners entertained.

Partly, of course, these differences reflected the different mediums through which popular images were conveyed in the mid-19th century—the free-wheeling colored woodblock prints of Japan, as opposed to the black-and-white (or delicately tinted) photographs and etchings of the West. In the wake of the Harris Treaty, Western photographers in Japan produced great numbers of photographs, and travelers and collectors snapped them up. The audience that actually saw these remained limited, however, for the technology for reproducing them in the mass media lay decades in the future.

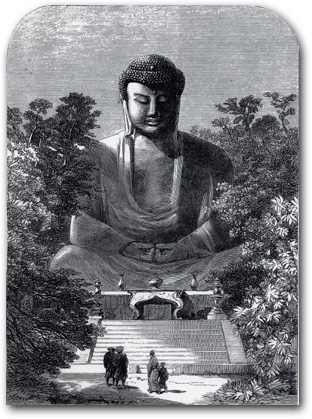

The “Great Buddha” at Kamakura was

typical of the scenes from Japan depicted in

Western publications.

Illustrated London News, February 25, 1865

|

In the United States and England, the general public thus relied largely on engravings and woodcuts in periodicals such as the Illustrated London News, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, and Harper’s Weekly for visual impressions of Japan. Like the photographs on which these illustrations were usually based, this remained a somewhat stiff and formal world, although the detail and “realism” could be fascinating.

Beyond the different modes of expression they relied on, however, Westerners and Japanese also tended to turn their gaze on different things. Since the new treaties restricted where foreigners could travel within Japan, it took a while before they had free access to great urban centers such as Edo or Osaka. Still, they did move about. They threw themselves into sightseeing. And, understandably, they tended to seek out some sort of quintessential “Japan”—scenic views and famous places, for instance, and all manner of social types from the high samurai official down to the shopkeeper, laborer, and courtesan. These were the images they valued as their keepsakes and for their periodicals back home.

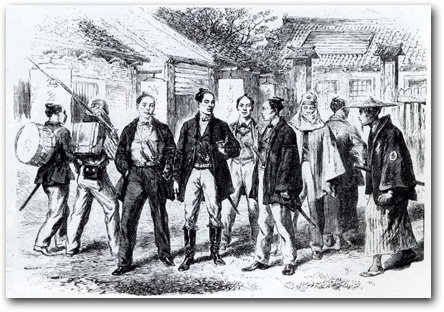

For Westerners, the foreign presence in Japan was of comparatively negligible graphic interest apart from skirmishes and incidents like the attacks on foreigners and reprisals that followed. “Westernization” was not the “real” Japan—and thus, in these early years, not deemed to be of particularly great interest beyond an occasional graphic that illustrated the curious spectacle of, say, Japanese samurai in Western dress with their famous two swords still tucked in their belts.

|

|

“Westernized” samurai, still wearing their distinctive two swords.

Illustrated London News, April 7, 1866

|

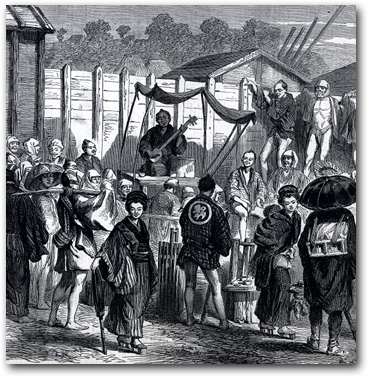

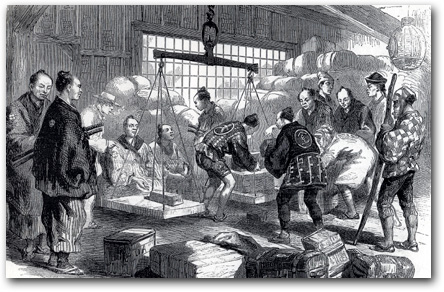

Even when addressing Yokohama, suddenly the center of Japan’s encounter with the West, magazines like the Illustrated London News tended to focus their gaze on the “Japanese-ness” of the place—a lively street scene packed with Japanese alone, for example, or men at work in a trading establishment where the single Caucasian present was barely discernible.

|

Street scene in Yokohama. (detail) Street scene in Yokohama. (detail)

Illustrated London News

August 10, 1861

|

|

|

|

A trading firm in Yokohama. (detail)

Illustrated London News, August 17, 1861 |

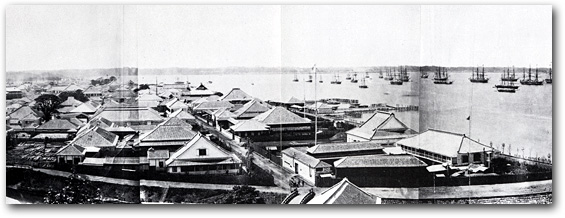

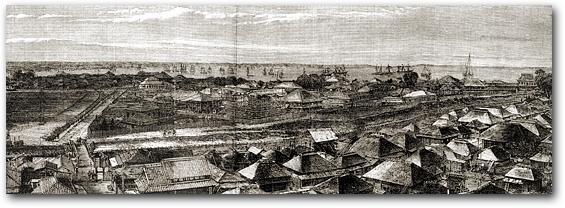

The illustrated Western periodicals did indeed offer their readers panoramic views of a scene that attracted Japanese artists as well: the foreign settlement and great harbor congested with foreign ships. Even here, however, the contrast was striking. The Western engravings, like the photographs on which they were based, kept the viewer at a distance. Here, for example, is a well-known photograph by the pioneer Western photographer in Japan, the Frenchman Felice Beato, together with an engraving of the same scene from the Illustrated London News:

|

Felice Beato’s famous photograph of “Yokohama from the Bluff” (detail). The fleet in the harbor is the combined foreign naval expedition that departed from Yokohama to attack Shimonoseki in 1864.

|

Panoramic view of Yokohama harbor. (detail)

Illustrated London News, October 29, 1864

|

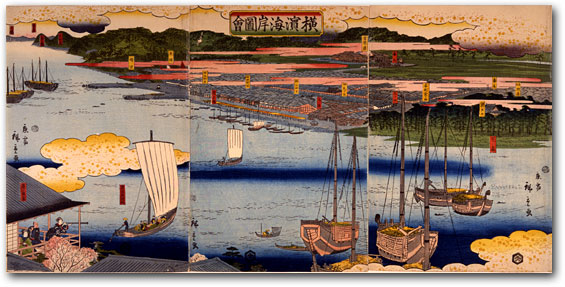

Compare, by contrast, the following panoramic “Yokohama prints” produced for a Japanese audience by the artists Sadahide and Hiroshige II soon after the harbor was opened to trade.

|

“Complete Picture of the Newly Opened Port of Yokohama” by Sadahide, 1859-60 “Complete Picture of the Newly Opened Port of Yokohama” by Sadahide, 1859-60

[Y0044] Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

|

The Japanese overviews draw us into scenes of remarkable aesthetic detail. In Hiroshige II’s two ambitious works, for example, we become one with a local woman with a telescope surveying the area with no Western ships yet in sight. (Stylized clouds flecked with gold leaf give this graphic the aura of a traditional painted screen.)

|

"Picture of the Coast of Yokohama" by Hiroshige II, 1860

[Y0050] Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

|

Or again, we ride in on a great foreign steamship that carries our eyes past the new settlement at Yokohama with its jutting piers and across green fields and wetlands, ultimately coming to rest on majestic Mount Fuji.

|

|

"Kanagawa, Noge, and Yokohama"

by Hiroshige II, 1861

[Y0056] Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

|

The “spin” in all this, however—and it is an amusing twist—is that Japanese depictions of “Yokohama” were, in their own way, as selective, incomplete, and misleading as depictions by the foreigners. These panoramic woodblock prints do bring the scene alive in ways photographs and engravings cannot match. Their elegant “realism” would enable a newcomer to the area to find his or her way around without getting lost. Once the artists actually moved on to producing prints of the foreigners and their daily life in Yokohama, however, they did not actually rely so much on first-hand observation. On the contrary, the inspiration for a large portion of their “Yokohama prints” or “Yokohama pictures” was pictures in other sources.

More precisely, they relied on the same popular publications that the Westerners were relying on for a picture of Japan—most notably, the Illustrated London News and the American weekly Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, both of which became available in Japan shortly after the ports were opened. These were the artists’ indispensable mirrors on “the West”—the sources in which they could find detailed depictions of Western fashions and domestic scenes and technological marvels like the big ships.

It was the melding of these printed foreign sources with the “real” Yokohama—and with the vibrant colors and conventions of the woodblock-print tradition—that gave ordinary Japanese their first dramatic glimpse of the “people of the five nations.”

|

|

|