| |

In retrospect, one of the most remarkable aspects of Commodore Perry’s momentous visits to Japan in 1853 and 1854 was that, despite the consternation they caused, no chaos ensued and no one was killed on either side. “Amity” did prevail.

Nothing of the sort can be said about the Harris Treaty and its aftermath. The unequal treaties inflamed patriotic samurai already smoldering with anger over abandonment of the once sacrosanct seclusion policy. And when these treaties actually came into effect beginning in mid 1859, they opened the door to unimagined kinds of chaos.

Traditional domestic markets and distribution routes were disrupted—bringing profit to some native entrepreneurs but economic disaster to a great many more. A skewed international exchange rate involving gold and silver precipitated an enormous drain of gold from Japan—forcing the Bakufu to drastically debase Japanese currency in 1860. (Within Japan, the gold-to-silver exchange rate was 1:5, meaning that one unit of gold could be purchased for five units of silver. The international rate, by contrast, was 1:15—meaning that a unit of Japanese gold would fetch 15 of silver outside Japan, which in turn could be used to purchase three more units of Japanese gold.)

Unemployment rose. Domestic prices soared sky high (conspicuous among them the price of rice and other cereals, silk and silkworms, tea, and sake rice wine). So precipitous was this inflation that in 1862 a city magistrate in Edo reported that living costs had increased by 50 percent. Coincidentally, largely due to disastrous harvests, much of Japan was wracked by famine in the mid 1860s. By 1867, the price of rice—the most basic of staples—had increased twelvefold in some areas.

As if all this were not curse enough, the foreigners also brought cholera with them, in all likelihood picked up in India while en route to Japan. Local reports spoke of tens and even hundreds of thousands of Japanese dying from outbreaks of cholera over the course of the years that followed.

Once they had arrived in the new treaty ports, moreover, more than a few traders and visiting seamen fell short of being exemplary goodwill ambassadors. They behaved, on the contrary, as might be anticipated in any largely male community planted far from its native soil. In Yokohama, as the historian Foster Rhea Dulles has recorded, by 1865 there were “five hotels, twenty-five grog shops, and an unrecorded number of brothels in the foreign settlement.” He might also have mentioned a “cow yard” that supplied the foreigners with beef, a horseracing track, gambling dens, and a particularly seedy neighborhood nicknamed “Bloodtown.”

Good Christians blanched at the “vice and impurity” young men fell into in Yokohama, where—as a distraught English clergyman put it—corrupt Japanese officials in the customs office helped them “negotiate… the terms of payment and selection of a partner in their dissolute mode of living.” One early foreign diplomat condemned these transplanted foreigners as “the scum of the earth,” while a French traveler lambasted “the insolent arrogance and swagger, the still more insolent familiarity, or the besotted violence, of many a European resident or visitor.”

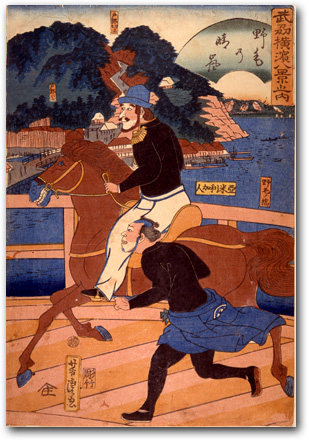

This swagger took various forms. Most of the earliest foreign residents, for example, came from previous postings in China rather than directly from their home countries. Many brought small horses or ponies with them, as well as firearms, and they quickly turned their new enclave in Yokohama into what one writer on the foreign settlements (Harold Williams) has described as “a fabulous Wild West type of town.” It was not uncommon to see them galloping

American with Japanese groom.

“Eight Views of Yokohama in Bushū:

Sunset Glow at Noge”

Yoshitora, 1861

[Y0121] Arthur M. Sackler Gallery

Smithsonian Institution |

through the streets firing pistols in the air, or engaging in target practice or even steeplechases in the countryside—indifferent to local people’s alarm. Sightseers barged into rural homes with their boots on. One particularly unrestrained coterie of foreign males went so far as to import a pack of hounds from Shanghai and thunder through the countryside—and rice fields—hunting boar, deer, and particularly foxes.

This was hardly endearing behavior by any standards. In feudal Japan, where public decorum was a virtue (and where only the samurai elite was permitted to ride horses), it fanned the fires of resentment already kindled by the Bakufu’s abandonment of seclusion.

In these unstable circumstances, all hell broke loose socially and politically throughout much of Japan. Peasant uprisings (hyakushō ikki) and urban riots (uchikowashi) took place with increasing frequency in the 1860s. Rebellious millennial movements (yonaoshi ikki) emerged promising “world renewal,” and in 1867 there was a massive and utterly startling outburst of ecstatic mass hysteria in which ordinary people abandoned their work and daily routines to dance and sing in the streets—sometimes cross-dressing and engaging in lewd behavior, and sometimes breaking into the houses of the wealthy and helping themselves to food and drink. (Participants in the latter outbursts became famous for exclaiming Eejanaika, or “Why not, it’s okay!”) Rumors spread like wildfire. And dissident samurai terrorists known as shishi—variously translated as “men of high purpose” or “men of spirit”—emerged to challenge the Bakufu and engage in acts of violence against the foreigners.

The shishi flourished in the decade that followed the Harris Treaty, and Japan became steeped in blood. There was, of course, a stunning symmetry in this, for it was not Japan alone that was wracked with upheaval in the decade that followed the opening of the treaty ports. Beginning in 1861, the United States also plunged into its own and vastly more murderous Civil War. To a very considerable degree, this turned American eyes away from Japan at the very moment that the handiwork of Perry and Harris had opened up a new world of opportunity.

In Japan, the rebels came almost entirely from the ranks of samurai, and they soon coined a potent slogan. Foreigners would be driven out. The Bakufu that had so cravenly let them in would be overthrown and replaced by a new source of power and legitimacy: the long impotent imperial family tucked away in Kyoto, which traced its lineage back to prehistoric (and, in fact, mythical) times. Sonnō jōi became the ubiquitous rallying cry of the shishi: “Revere the emperor, expel the barbarians.”

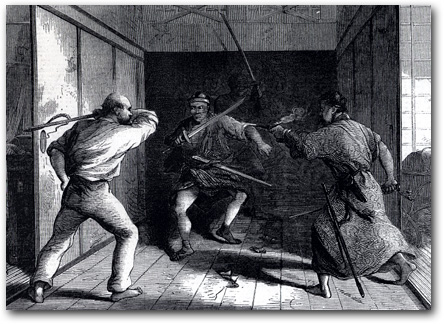

Bakufu officials as well as foreigners were murdered. Ii Naosuke, a high official who played a leading role in the signing of the Harris Treaty, was assassinated in March 1860. In January 1861, unknown swordsmen killed Henry Heusken, the young Dutch secretary and translator for Townsend Harris, in the streets of Edo; he was the seventh foreigner murdered within 18 months. Some months later, shishi burst into the British legation in Edo, killing two consular officials with their swords and seriously wounding another. In the sensational Richardson Affair of September 1862, several brash Englishmen rode their horses into the retinue of the lord of Satsuma on the highway near Yokohama. The daimyō’s enraged retainers killed one of them, Charles Richardson, and wounded two of his companions. (A fourth person in Richardson’s party, an English woman, escaped unharmed.) In May 1863, arsonists torched the U.S. legation in Edo.

|

|

Japanese terrorists

attack the British

legation in Edo

in 1861. (detail)

Illustrated London News, October 12, 1861

|

In August 1863, in retaliation for the still festering Richardson Affair, a British fleet of seven warships bombarded Kagoshima, the capital “castle town” of Satsuma in the southernmost part of Japan, resulting in the destruction by fire of a large part of that port city.

|

British fleet bombarding Kagoshima in August 1863. (detail)

Illustrated London News, November 7, 1863 |

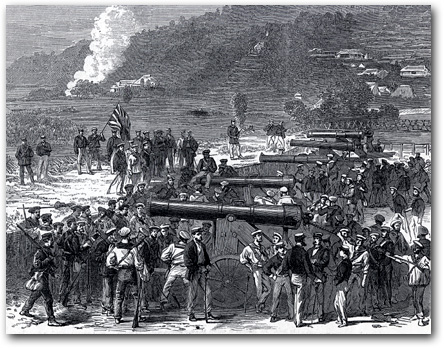

That same summer, a U.S. warship sank two vessels belonging to Chōshū, another powerful daimyō domain, after Chōshū had fired on foreign ships passing through the Straits of Shimonoseki in the southwest. A year later, in the summer of 1864, a combined British, French, Dutch, and U.S. fleet—17 warships in all—bombarded Chōshū’s defenses at Shimonoseki for four days, routed the domain’s forces, and spiked the coastal batteries. Unlike at Kagoshima, however, they spared the city itself.

|

|

Felice Beato’s well-known photograph of British marines with captured shore batteries at Shimonoseki, September 5, 1864.

|

Illustrated London News rendering of the captured batteries in Shimonoseki, published in the December 24, 1864 issue. Illustrated London News rendering of the captured batteries in Shimonoseki, published in the December 24, 1864 issue. |

|

Through all this, the beleaguered Bakufu was caught between a rock and a hard place—challenged by domestic opponents for failing to keep out the barbarians, and challenged by the foreigners for failing to protect them from these same domestic rebels. It did not help that the foreign powers demanded that the Bakufu publicly execute some of the samurai involved in anti-foreign acts.

|

Execution of a samurai involved in the 1861 attack on the British legation in Edo. (detail)

Illustrated London News, February 25, 1865. |

The foreigners also demanded large indemnities. In 1863, for example, the Bakufu agreed to pay the British 100,000 pounds as compensation for the Richardson Affair. In 1864, it was forced to agree to an indemnity of $3,000,000 as reimbursement for the expense of the foreign expedition against Shimonoseki. These were huge sums, and served to further deplete not only the government’s treasury but also its credibility in the eyes of domestic critics.

|

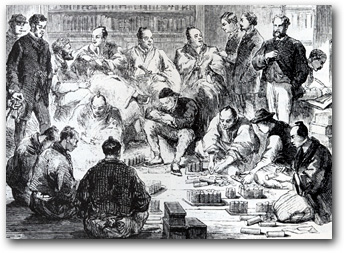

Representatives of Satsuma fief paying an indemnity to the British for the Richardson Affair, following the British bombardment of Kagoshima. (detail) Representatives of Satsuma fief paying an indemnity to the British for the Richardson Affair, following the British bombardment of Kagoshima. (detail)

Illustrated London News

February 20, 1864 |

|

Eventually, open warfare erupted between the Bakufu and its internal enemies, with opportunistic Westerners supplying both sides with arms. Woodblock artists wallowed in reportage of mayhem—horsemen burdened with severed heads, gunfire blowing people sky high, defeated samurai commiting suicide, landscapes roiled by pitched battles.

|

The final days of the Bakufu in 1868 as captured in a print by

Yoshitoshi done six years later.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

|

Most of the shishi terrorists died violently, but they did not die in vain. The Harris Treaty rang the death knell for the Bakufu: less than 10 years later, as 1867 turned into 1868, the shogun’s government was overthrown by dissident samurai acting in the name of the emperor—a shadowy presence who had not wielded real power for centuries. This was the famous “Meiji Restoration” that set Japan on a course of pell-mell industrialization and “Westernization.” The radical shishi who did survive this decade of fury quickly threw off, not merely terror, but anti-foreign agitation as well. They proved themselves pragmatists—Western-style nation builders—and became the revered founding fathers of modern Japan. History does enjoy its little jokes.

|

|

|