| |

Although much war photography was stiff, formal, and tedious, certain photos conveyed a gritty “realism” that no other mode of illustration—whether it be woodblock prints or paintings or cartoons—could match. And as it happened, much of this photography reached its audience in the form of postcards.

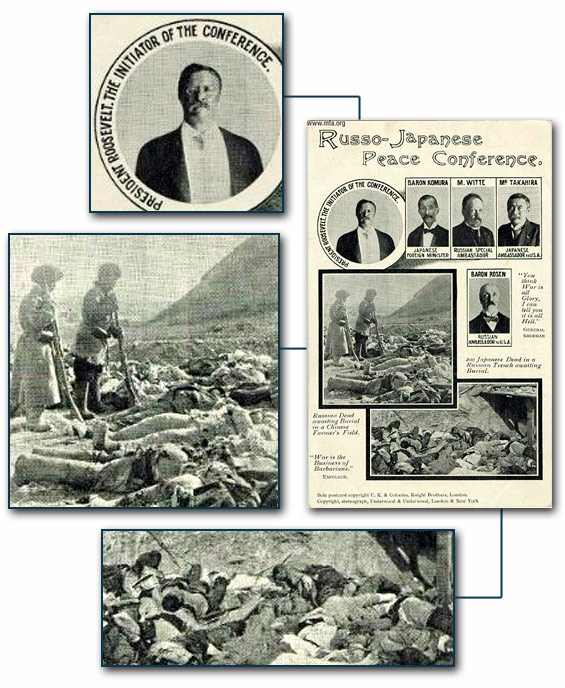

Even a small sample of photo postcards of the Russo-Japanese War suggests the way photography captured moments that would have appeared genuinely new and impressive to most people at the time. When the war ended with a peace conference convened in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, by President Theodore Roosevelt, for example, an English manufacturer responded with a composite postcard that included not only portraits of major dignitaries at the conference but also grisly images of the carnage on both sides. No other medium could have brought home the meaning of war and peace so dramatically.

|

|

The Russo-Japanese War ended with a peace conference at Portsmouth, New Hampshire, sponsored by U.S. president Theodore Roosevelt in September 1905. This British postcard juxtaposes portraits of major participants at the conference and photos of the human costs of the conflict. The Russo-Japanese War ended with a peace conference at Portsmouth, New Hampshire, sponsored by U.S. president Theodore Roosevelt in September 1905. This British postcard juxtaposes portraits of major participants at the conference and photos of the human costs of the conflict.

“Russo-Japanese Peace Conference” (postcard with details enlarged)

[2002.5526]

|

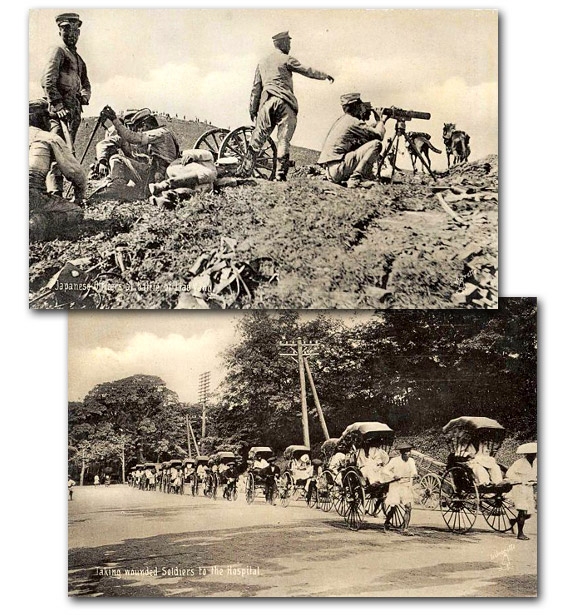

Other photo postcards succeeded similarly in freezing certain scenes in an arresting manner—infantry surveying the battlefield through a telescope, for instance, and “wounded soldiers” being delivered to a hospital in a disconcertingly serene row of coolie-pulled rickshaws. (It is unclear if the injured men are Japanese or Russians captured and cared for by the Japanese—the latter act being a humanitarian gesture the Japanese took great care to emphasize in their own postcard propaganda.)

|

|

Photographs introduced unique themes, subjects, and perspectives to the new vogue of picture postcards. These British cards capture Japanese infantry at rest and wounded soldiers being taken to a hospital in rickshaws. Photographs introduced unique themes, subjects, and perspectives to the new vogue of picture postcards. These British cards capture Japanese infantry at rest and wounded soldiers being taken to a hospital in rickshaws.

“Japanese Officers at Battle of Liao-Yang”

[2002.4020]

“Taking Wounded Soldiers to the Hospital”

[2002.4018]

|

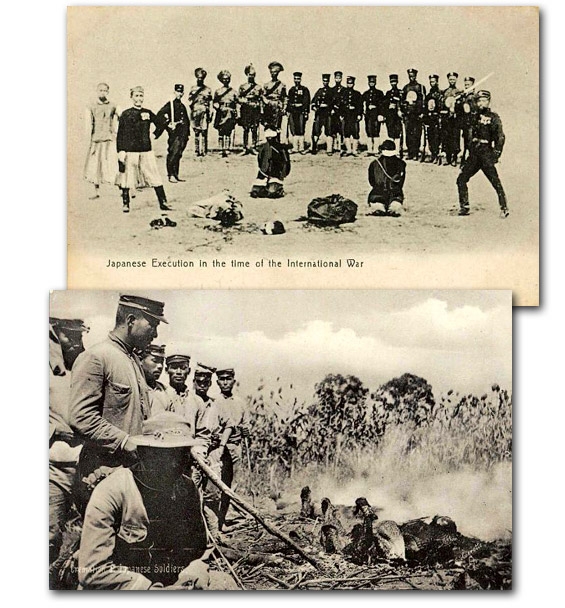

The English clearly found particular titillation in “peculiarly Oriental” images of the latter sort. Their postcard offerings, for example, also include a puzzling photo cryptically captioned “Japanese Execution in the time of the International War,” in which the Japanese are beheading Asians (not Russians) and bystanders include turbaned Commonwealth observers. Another photo postcard, less perplexing but no less jarring, features Japanese soldiers cremating their dead.

|

|

Some British photo postcards were obviously offered for their shock effect, as seen in these scenes of an execution and the cremation of Japanese war dead. The execution scene is actually puzzling, for the victims are Chinese rather than Russians and the impassive observers include soldiers from India. Some British photo postcards were obviously offered for their shock effect, as seen in these scenes of an execution and the cremation of Japanese war dead. The execution scene is actually puzzling, for the victims are Chinese rather than Russians and the impassive observers include soldiers from India.

“Japanese Execution in the Time of the International War”

[2002.4031]

“Cremation of Japanese Soldiers”

[2002.4017]

|

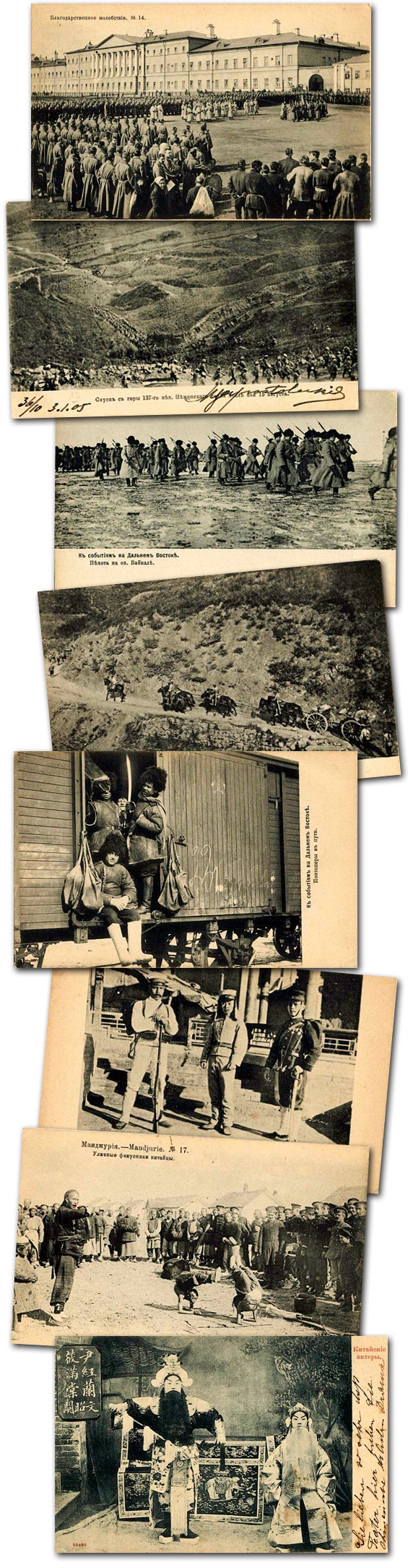

Russian postcard manufacturers relied particularly heavily on photos. A few of these offerings convey a sense of the forbidding landscape of Manchuria, where the great land battles took place. Some focus on military parades and send-offs in the homeland. Camerawork was perhaps most effective in capturing small groups of soldiers—such as the Cossacks—en route to the front. Russian postcards also included straightforward “representative” photos of the Japanese foe, as well as an occasional “tourist” shot of exotic China.

|

|

Russian photo postcards, which were geared to the domestic Russian audience, ranged from formal parades to troop deployments in Manchuria to depictions of Japanese soldiers to touristy pictures of Chinese acrobats and opera performers. Russian photo postcards, which were geared to the domestic Russian audience, ranged from formal parades to troop deployments in Manchuria to depictions of Japanese soldiers to touristy pictures of Chinese acrobats and opera performers.

“Soldiers in a Ceremony”

[2002.3868]

“Russian Soldiers in a Mountain Battle”

[2002.3879]

“Russian Soldiers in the Field”

[2002.3865]

“Traveling Troops in the Mountains”

[2002.3887]

“Russian Soldiers on a Train””

[2002.3861]

“Japanese Soldiers”

[2002.3878]

“Russian Soldiers Watching Chinese Acrobats ”

[2002.3880]

“Chinese Opera Singers”

[2002.5542]

|

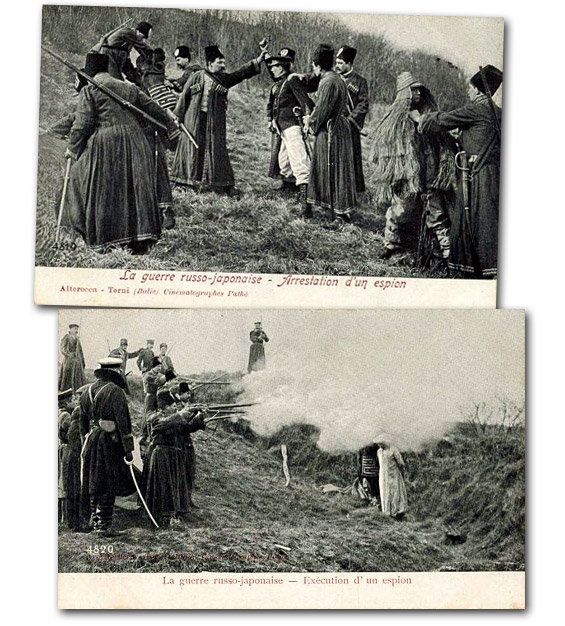

Photographs do not necessarily convey “truth,” of course, and some samples of ostensible postcard realism were obviously staged. An Italian photographic depiction of the arrest and subsequent execution of Japanese “spies” is particularly delectable in this regard, for the scenes might well have come from an opera. All that is missing is the soprano jumping off a balustrade.

|

|

These obviously staged postcards, produced in Italy, call to mind an operatic melodrama. They purport to show the capture and execution of Japanese spies. These obviously staged postcards, produced in Italy, call to mind an operatic melodrama. They purport to show the capture and execution of Japanese spies.

“The Russo-Japanese War: Arrest of a Spy”

[2002.3917]

“The Russo-Japanese War: Execution of a Spy”

[2002.3918]

|

Paintings and drawings offered a livelier and more literally colorful sort of “realism” to the public interested in following the Russo-Japanese War. Indeed, we have become so used to being surrounded by splashy mass-produced graphics that it is necessary to remind ourselves how marvelous such images seemed to be at the beginning of the 20th century. An entirely new national and international audience had opened up for commercial art, and artists responded with enormous energy—sometimes working from photographs, sometimes from battlefield sketches, sometimes letting their imaginations run free based on a general understanding of uniforms and armaments and the general nature of the mayhem taking place on the other side of the world.

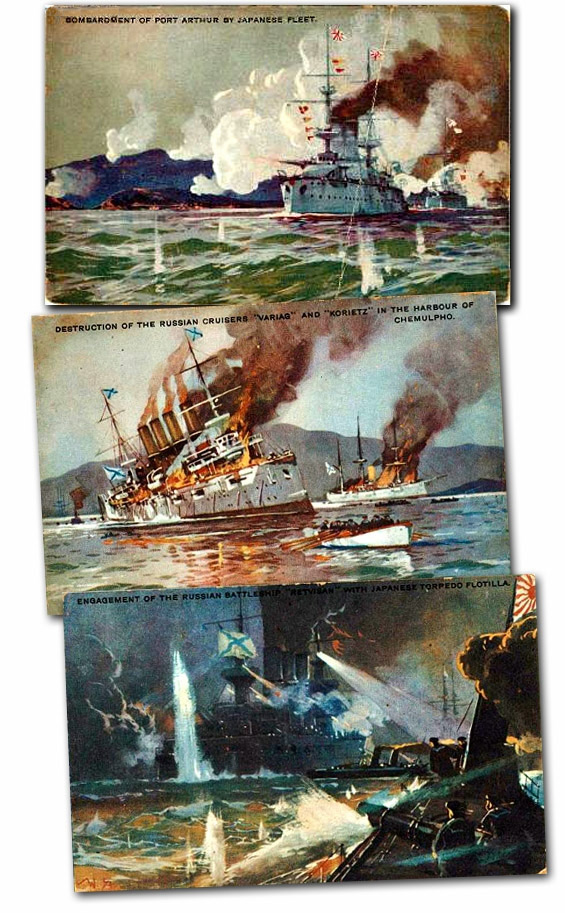

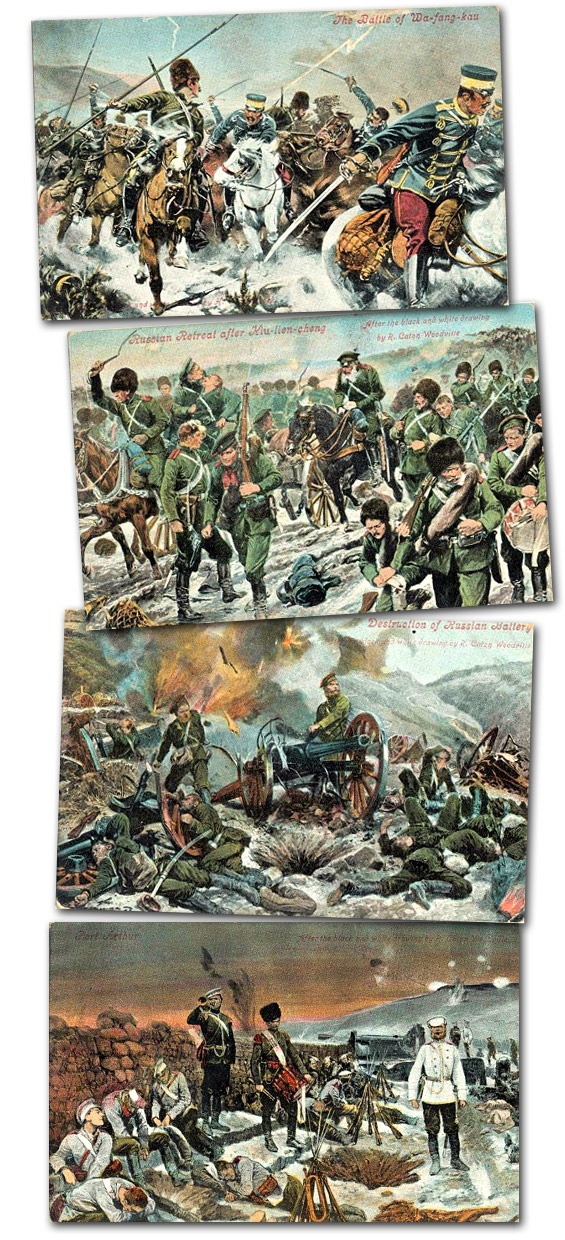

Painterly English renderings of the war at sea convey a sense of the more romantic approach to such ostensible realism. By contrast, an English series depicting great land battles captures the dynamism with which these more easily humanized confrontations could be brought to life by skillful painters.

|

|

These dramatic naval scenes are part of a British series. As seen here, postcard artwork sometimes includes the signature of the artist. These dramatic naval scenes are part of a British series. As seen here, postcard artwork sometimes includes the signature of the artist.

“Bombardment of Port Arthur by Japanese Fleet”

[2002.5580] & [2002.3925]

“Destruction of the Russian Cruisers ‘Variag’ and ‘Korietz’

in the Harbour of Chemulpho”

[2002.3926]

“Engagement of the Russian Battleship ‘Retvisan’ with

Japanese Torpedo Flotilla”

[2002.3922]

|

|

The fury and human suffering of the battlefield is emphasized in this realistic British series. These color postcards were based on black-and-white drawings by artists in the field. The fury and human suffering of the battlefield is emphasized in this realistic British series. These color postcards were based on black-and-white drawings by artists in the field.

“The Battle of Wa-fang-kau”

[2002.3990]

“Russian Retreat after Kiu-lien-cheng”

[2002.3986]

“Destruction of Russian Battery”

[2002.3988]

“Port Arthur”

[2002.3992]

|

Some postcard illustrations that were explicitly identified as being based on photos carried realism in unexpected directions. One such English offering, for example, depicts “Japanese Soldiers paying respect to Russian Graves”—a scene the heathen Japanese would have been pleased to include in their own war graphics as evidence of their tolerant and “civilized” behavior. A less flattering photo-turned-painting in the same series pictures a Japanese soldier painting a circle on the cheek of a Chinese coolie “for identification.”

|

![“Japanese Soldiers Paying Respect to Russian Graves” Artist unknown [2002_3905] Leonard A. Lauder Collection, Museum of Fine Arts Boston](image/2002_3905_s.jpg) |

“Japanese Soldiers Paying Respect to

Russian Graves”

[2002.3905]

|

“Marking

Coolie

for Identifi-

cation”

[2002.3904]

|

![“Marking Coolie for Identification” Artist unknown [2002_3904] Leonard A. Lauder Collection, Museum of Fine Arts Boston](image/2002_3904_s7632_Copy.jpg) |

These British illustrations are based on photos from the war zone. Japanese took great care to demonstrate their “civilized” behavior to the international community, and paying respect to the Russian war dead was one aspect of this (top). The second scene (bottom), depicting a Japanese soldier painting an identification mark on the cheek of a Chinese “coolie” recruited for manual labor, is more unusual. These British illustrations are based on photos from the war zone. Japanese took great care to demonstrate their “civilized” behavior to the international community, and paying respect to the Russian war dead was one aspect of this (top). The second scene (bottom), depicting a Japanese soldier painting an identification mark on the cheek of a Chinese “coolie” recruited for manual labor, is more unusual.

|

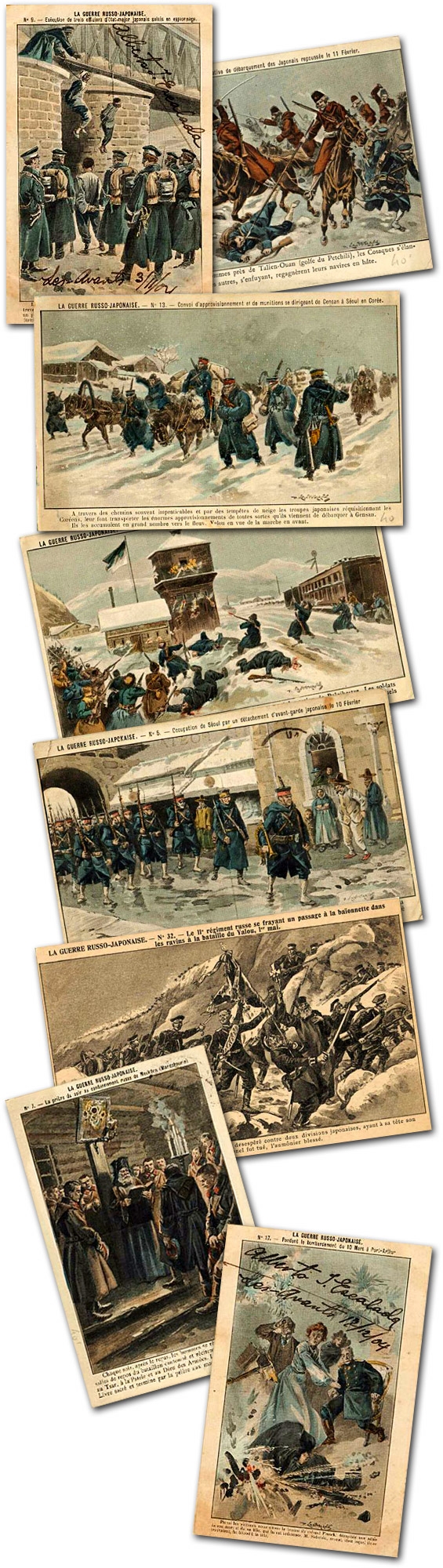

Postcard realism might also be enhanced by imbedding unsentimental illustrations in sufficient text to make them resemble excerpts from the popular press rather than independent pieces of artwork per se. A run of French postcards in this vein, for example, includes Russians hanging Japanese accused of “espionage,” fighting men battling and marching and engaging in street fighting in the snow, Japanese infantry occupying Seoul while Korean bystanders look on. A few of these strong graphics depict Russian Orthodox priests attempting to rally or comfort the troops. A few take the Japanese bombardment of Port Arthur into the parlors of the resident Russian community, where fashionable women as well as men suddenly find their lives blown to smithereens—like a heart-stopping scene from an epic French or Russian novel.

|

|

These gritty French postcards, with their extended captions, have the flavor of bonafide journalistic reportage. Executions, battlefield savagery, snow and bitter cold, occupation forces, priests accompanying the Russian troops, bombardment of civilian quarters—all have a place in this run of “realistic” postcards. These gritty French postcards, with their extended captions, have the flavor of bonafide journalistic reportage. Executions, battlefield savagery, snow and bitter cold, occupation forces, priests accompanying the Russian troops, bombardment of civilian quarters—all have a place in this run of “realistic” postcards.

“Execution of Three Japanese Administrative

Officers Captured while Spying”

[2002.4001]

“Repulsion of the Japanese Attempt to Land, 11 February”

[2002.4000]

“Convoy of Supplies and Munitions Heading

for Gensan in Seoul, Korea”

[2002.4003]

“Attack of a Manchurian Railway Station by

the Tanghouzes, 29 February”

[2002.4004]

“Occupation of Seoul by a Detachment of Japanese

Advance Guards, 10 February”

[2002.3998]

“The Second Russian Regiment Opening up a Passage with

Bayonets in the Ravines at the Battle of the Yalu River”

[2002.3896]

“Prayer at Night in the Russian Quarters in Mukden”

[2002.3999]

“During the Bombardment of 10 March at Port Arthur”

[2002.4006]

|

Japanese postcard art of the Russo-Japanese War also includes gritty and graphic photos, paintings, and drawings—often, indeed, done in “Western” style. Yet in the final analysis, the foreign postcards tend to have their own unique take on events, and their own distinctive styles. “Realism” itself lay, as always, partly in the eye of the beholder.

|

|

|