| |

HOPE DEFERRED

While the experience of being on the street, arm-in-arm with other protestors, may have been transformative to those involved, the protests were a bitter and often violent struggle over what road Japan should take, where it should stand in the world, and what place people would have in the workings of their government. In addition to the police, anti-treaty protestors also confronted opposition from right-wing groups.

|

|

| |

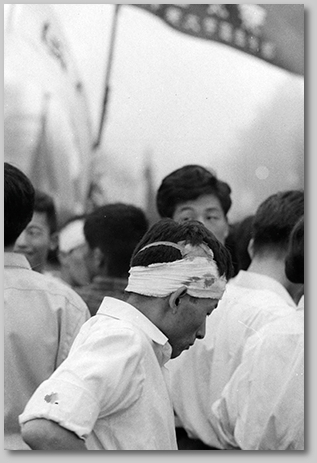

Pro-American Demonstrators

Though far outnumbered by other demonstrators, conservative and pro-American counter-protestors played a conspicuous role during the Anpo protests. Shortly after stepping down as prime minister, Kishi himself was attacked by a right-wing extremist and stabbed multiple times in the leg. Some months after the protests, on October 12, 1960, Asanuma Inejirō, the head of the Japan Socialist Party, was assassinated by a 17-year-old fanatic while giving a public address.

|

|

| |

On May 26, three young right-wing assailants threw a bottle filled with ammonia at Socialist Party leaders gathering signatures outside the Diet compound. This foreshadowed the assassination of the head of the Socialist Party, Asanuma Inejirō, several months later.

[anp7131]

|

|

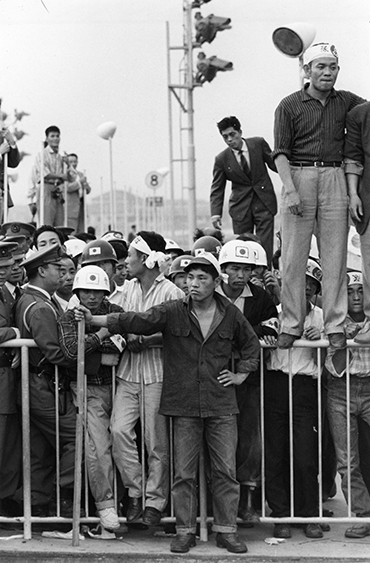

right: Pro-American youth gather at Haneda airport on June 10 to welcome the delegation led by White House Press Secretary James Hagerty. right: Pro-American youth gather at Haneda airport on June 10 to welcome the delegation led by White House Press Secretary James Hagerty.

[anp7127]

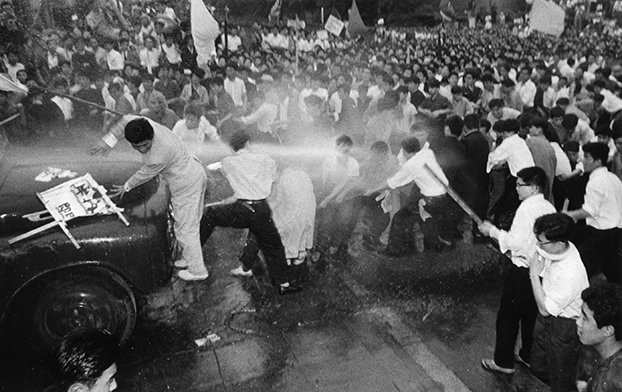

below: They scale a fence to attack anti-treaty protestors whose signs include one declaring “We Dislike Ike”

(a reference to President Eisenhower’s campaign slogan).

[anp7128]

|

|

|

| |

Protestors clashed with police on many occasions over May and June, but no day was more fierce than June 15. Planned as a “second May Day,” it started with a general strike. A protest march on the Diet began in the afternoon. By 4:00 p.m., a group of around 10,000 students from the mainstream of Zengakuren had gathered near the south gate of the Diet building. By 6:00 p.m., the students had succeeded in prying open the gate and began trying to enter the compound, squeezing between the trucks that had been put there as a barrier. The police fended them off with water cannons, and, around 7:00 p.m., launched a counterattack using clubs to drive the students back. It was sometime during this clash that Tokyo University student Kanba Michiko was killed.

In response to the embarrassment of the Hagerty incident a few days earlier, the government had put the police on high alert and mobilized nearly 3,500 in and around the Diet compound. The clashes between the students and police went back and forth until after midnight, resulting in the arrest of 200 students and the hospitalization of 600 more—including 50 who required over three weeks to recover. [27] Many police were also injured. [28] Hamaya was at the south gate for these clashes and his photographs of them are the single most sustained passage in his book.

|

|

| |

June 15

On the evening of June 15, students led by the radical Zengakuren federation forced their way into the Diet compound through the south gate, clashing with police for several hours before they were finally driven out. The violence surrounding this incident, which included police attempts to disperse the demonstrators with fire hoses, became a turning point in the protests. Hundreds of students and scores of police were injured, and one student was killed.

Hamaya’s photographs convey the tension and fury of the June 15 confrontation. Partly due to low light the photos are more blurred than others, but perhaps even because of this they succeed in communicating the shock of the clash and the fluid nature of unfolding events. Many of the shots are taken looking down from where Hamaya stood, either on a ledge or photographer’s ladder. The angle serves to emphasize the dislocation of injury, the isolation of the fallen, and the rawness of the chaos. Protestors are stripped of their shoes and the signs they had been holding—and indeed of their individual identities. This is the only sequence in Hamaya’s coverage of the protests where people are dehumanized and frenzy takes over.

|

|

|

| |

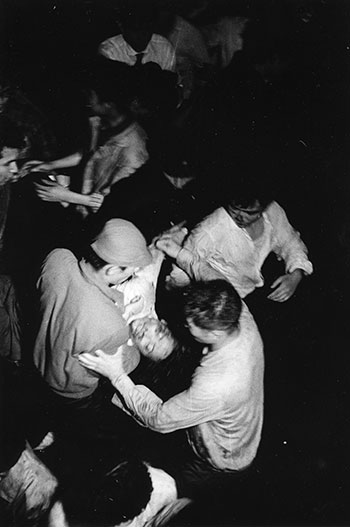

The following photo is the most disturbing of all of Hamaya’s images, and the most remarkable result of his proximity to the June 15 confrontation. Although impossible to verify with complete certainty, it depicts what is probably the body of Kanba Michiko, a female university student and activist, being carried out of the melee. In his autobiography, Hamaya writes that during an exhibition of his photos after the protests, Kanba’s mother informed him directly that it was her daughter in this picture. [29]

|

|

|

| |

The night of June 15 was a turning point in the protests. It led Kishi to cancel President Eisenhower’s visit for fear of the embarrassment that massive protests or some other incident might cause. It also caused an irreparable split among the protestors. The Communist and Socialist Parties had long been critical of Zengakuren’s use of direct action, while the radical students likewise disparaged the two parties’ accommodating behavior, apparently aimed more at preserving their small seat at the table of parliamentary democracy than tackling fundamental problems. The incidents on June 15 and the recriminations that followed were the straw that broke what had always been an uneasy alliance between them. Poet, critic, and friend of the students, Yoshimoto Takaaki, called it the “end of fictions,” an important milestone and symbol in the development of Japan’s student movements of the 1960s. [30]

The events of June 15 also caused a shift in the attitude of the media and public opinion. The violence of the police had until this time kept the media and the public on the side of the students and protestors in gereral, but the storming of the Diet compound provoked disapproval. In an unprecedented action, all seven of Japan’s major daily newspapers published a joint editorial on June 16 that condemned the use of violence. Though the editorial laid ultimate responsibility for the situation with the government itself, it was clear to everyone that the students were the primary target of criticism, and the conservatives welcomed the editorial as vindication.

Many protestors, however, were outraged, as was Hamaya himself. His afterword to his published selection of protest photos is an implicit repudiation of the editorial, arguing that violence was already inherent in a political system that excluded citizen’s voices. His photographic representation of the aftermath of June 15 similarly ignores the political fallout, to concentrate instead on the manifestations of grief and mourning they generated. Kanba Michiko would become a martyr, her name still remembered today among members of the Anpo generation. Sociologist and historian Oguma Eiji has argued that people saw in her a personification of the ardent, principled purity of youth, and that her death was a traumatic turning point because it brought back memories of the countless youth lost during the war. [31]

In Hamaya’s photos, the grief on the faces of the students blends into the defeat he records a few days later, the day the treaty went into effect. It is on these faces, and all of the others in the collection, that we can see the connection between the large and the small, the global and the personal, most clearly. Rather than losing the larger picture in detail, it is these details that portray the event as something that happened in the accumulation of individual experiences, simultaneously mundane and extraordinary.

|

|

| |

Days of Grief

The days following the violence of June 15 saw many momentous events—a memorial service for Kanba Michiko on June 18, the automatic coming into effect of the revised security treaty on June 19, and a third general strike on June 22.

Hamaya’s focus in his final photos was not on confrontation but, above all, on grief and mourning for a dead colleague and a defeated movement. Kanba Michiko would become a martyr, her name still remembered today among members of the Anpo generation.

|

|

| |

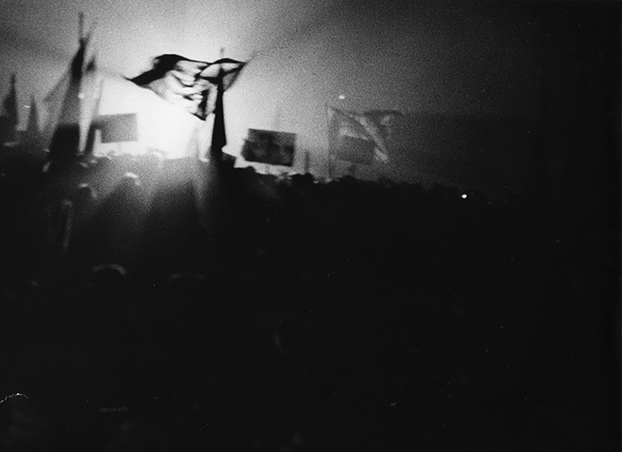

Hamaya’s caption for this June 15 photo reads: “The news of a female student’s death spread. A few thousand students entered the [Diet] compound which had been yielded by the police. Night fell amidst a light rain. Grief flowed among them. At 9:10, they furled their flags and offered silent prayers to their classmate. The rain grew noticeably stronger.”

[anp7167]

|

|

| |

Mourners gather in the vicinity of the Diet building on June 16, bringing flowers and creating makeshift shrines in Kanba’s memory.

[anp7171] |

|

| |

Kanba Michiko’s portrait as it appeared in a memorial service at the University of Tokyo on June 18.

[anp7176] |

|

|

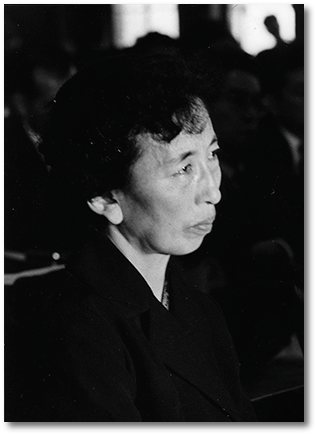

Kanba’s mother (left) joined students and professors (below) at the June 18 funeral service. Kanba’s mother (left) joined students and professors (below) at the June 18 funeral service.

[anp7177]

|

| |

After the June 18 memorial service, students march towards the Diet with Kanba’s portrait. This was the last day before the Anpo treaty would pass into law, and the peaceful protests around the Diet were the largest ever, with an estimated 330,000 participants.

[anp7047] |

|

|

An injured Zengakuren student on the morning of June 19, the day the Anpo Treaty became law. An injured Zengakuren student on the morning of June 19, the day the Anpo Treaty became law.

[anp7185]

|

Hamaya’s account of the Anpo protests ends abruptly and ambivalently. Where did these massive protests lead? What did they mean for the future? Hamaya’s final images strike an optimistic note. They are taken during the preparations for the third general strike that month—on June 22, three days after the revised security treaty went into effect—and are some of the most affectionate in the whole collection. Strikers and students bed down together, lean on each other, and sing. |

|

Strikers, students, and other supporters dance and sing on the eve of the general strike on June 22. Collective singing, often accompanied by the accordion, was a central element of the culture of protest in the 1950s. Strikers, students, and other supporters dance and sing on the eve of the general strike on June 22. Collective singing, often accompanied by the accordion, was a central element of the culture of protest in the 1950s.

[anp7186]

|

| |

A sit-in on a train station platform.

[anp7061]

|

|

| |

The final image in Hamaya’s published selection of protest photographs frames a

peaceful march as it advances down a wide avenue directly toward the camera. Hayama’s commentary reads: “Today, the people of Japan joined hands with one another, spread their hands out wide, and set out striding forward in order to continue living as the people of their day. In order to live in a democracy.” The implication is that, although the treaty itself became law, a higher goal might have been achieved. Kishi was being forced from office, and in the process a wide and varied multitude of Japanese people had emerged to defend the principles of democracy. That engagement would continue. This was a common reading of events that Hamaya endorsed at the time, but would soon come to question.

|

|

|

| |

After photographing the June 22 general strike, Hamaya turned his lens away from the popular protests that continued at less intense levels in later months and years, returning only very briefly to the subject of student protest in the late 1960s. His final images of the Anpo struggle, however, strike an optimistic note. This photo, the concluding shot in the collection he published in Japan in August 1960, carries a caption stating that although the protests failed to prevent the new security treaty from going into effect, they succeeded in creating a deeper spirit of grassroots democracy.

[anp7193]

|

|

| |

But, the optimistic view was not shared by everyone. If some saw the Anpo protests as basically successful, others saw only failure. The protests had failed to stop the revised security treaty, and in the process demonstrated Japanese democracy’s fundamental lack of responsiveness to the voice of the people. This view was most common among student radicals, but it was also shared among some leading intellectuals. For all of the upheaval of the protests, when Kishi stepped down and another member of his party, Ikeda Hayato, took his place on July 19, political factionalism and money politics returned as they had always done. Nothing had changed.

The Anpo protests did indeed evaporate quickly following the passage of the treaty and Kishi’s resignation. The social movements that had fed into the protest, as well as some that were born during them, would continue into the 1960s and beyond, but no protest would bring together so many different strands of social interest again. The year 1960 marked the beginning of the “income doubling plan,” inaugurated by Prime Minister Ikeda in the wake of the protests. As economic growth and personal incomes soared through the 1960s, many people’s interest shifted away from the politics that had driven the Anpo protests. The year 1960 saw the highest-ever rate of hiring success for college graduates in the postwar period, and a special edition of the weekly magazine Shūkan Bunshun from June 27, 1960 might have been the first to capture the shift in attention with its title, “So the Protests are Over, Let’s Find a Job.” [32]

Whether the Anpo protests were a success or a failure, a beginning or an end, a turning point or a continuation, continue to be questions with many answers. For Hamaya, the outcome of the protests seemed to become increasingly disappointing. After completing his exhausting coverage of the “days of rage and grief,” he took a hiatus from photographing human subjects, one which ended up becoming definitive of his subsequent work. After traveling Japan for four years, he published a collection of nature photography titled Landscapes of Japan (Nihon Rettō), and after this he only rarely photographed human subjects. In the afterword to the collection of landscapes he talked about the reason behind the transition. Speaking of the Anpo protests, he wrote:

The Japanese, who had passed a long history up until that time as though they had no relation to politics, suddenly showed at this particular moment in history an unexpected and elevated awareness of politics. I thought this was a rare moment of progress. But it was only a passing occurrence. … the momentary elevation soon fell away. Superficial economic progress came after the political strife. But this kind of unstable peace and prosperity, driven by economic development, was false.

Hamaya’s 1960 book of photos of the protests ends on a positive note; nevertheless, the image of a single forlorn flag, marking dawn on June 19, the day the treaty became law, remains one of the most arresting of the collection. It seems to mark something left undone, a hope or aspiration that did not reach its fulfillment.

|

|

|

| |

June 19, the day the treaty became law.

[anp7183] |

|

|