| |

THE CONFRONTATION

Serious discussion of revising the security treaty began in the late 1950s. By then Japan was a different country than it had been in 1951 when Yoshida negotiated the first treaty. Phenomenal economic growth through the 1950s (7% on average between 1952 and 1958, and 13% from 1959 to 1961) had given people renewed confidence and optimism about the future. On the international stage Japan normalized relations with the Soviet Union in 1956 (without concluding a peace treaty) and joined the United Nations the same year. These changes made the “unequal treaty” of 1951 seem increasingly inappropriate. Added to this were new doubts as to the relative strength of the United States. While conservatives had long argued that the alliance made Japan safer, the Soviet’s spectacular success in launching Sputnik in 1957 sowed doubts about whether Japan had really sided with the winner. Thus the debate over a revised security treaty threatened to reopen all of the basic questions about Japan’s identity and place in the world.

The new treaty, negotiated by Prime Minister Kishi, answered some of the criticisms of the previous security treaty. It obligated the U.S. to “act to meet the common danger” should Japan be attacked. It established that the U.S. would “consult” Japan before launching attacks on enemies from bases in Japan. It removed the clause on domestic disturbances. It squarely acknowledged the primacy of the U.N. charter. And it had a time limit of 10 years, after which either side could dissolve it.

Nevertheless, much doubt remained and, as the debate over ratification wore on in the Diet through winter and spring of 1960, public skepticism mounted.

A blizzard of books, pamphlets, and magazines raised serious questions about the new treaty. Did the promise that the two parties would “consult” actually give Japan any veto power over U.S. troop movements in Asia? Didn’t this risk embroilment in a foreign conflict? Why not limit the mission of U.S. forces in Japan to the protection of Japan? Did “act[ing] to meet a common danger” in fact commit the U.S. to defend Japan? Wasn’t 10 years too long a time in such a fast-changing world? Why didn’t the Japanese government insist on banning nuclear weapons? As the questions multiplied, it began to seem the new treaty left Japan’s position little changed from the old one.

An organized opposition called the People’s Council to Stop the Revised Security Treaty (Anpo Jōyaku Kaitei Soshi Kokumin Kaigi) provided an umbrella for hundreds of organizations that were opposing the new treaty. Growing out of the many citizen movements of the 1950s, the opposition under the People’s Council was broad and varied. When the council formed in March 1959 it counted 134 organizations among its members, but by the following March this had grown to 1,633 affiliated organizations, including labor unions, farmers’ and teachers’ unions, student groups, women’s organizations and mothers’ groups, the Socialist and Communist Parties, anti-nuclear organizations, poetry circles, theater troupes, and a plethora of others. [15]

The long-running opposition mounted by the People’s Council was significant, centering around “united actions” (tōitsu kōdō) during which its constituent organizations held rallies, strikes, and protests around the country. But this alone does not account for the scale of the events that erupted in May and June, 1960. An estimated 16 million people took part in anti-treaty protests between the spring of 1959 and the fall of 1960. [16] Roughly half of these were concentrated in May and June 1960, however—a massive popular upsurge that outstripped any organization’s claim of leadership. [17] The trigger for the upsurge was events that unfolded in the Diet on the night of May 19, 1960.

In January, Prime Minister Kishi traveled to the U.S. to meet with President Dwight D. Eisenhower and sign the revised treaty. During the visit, Eisenhower promised to visit Japan in June, by which time Kishi hoped to have the treaty ratified by the Diet. But opposition both inside and outside the Diet successfully delayed the ratification for months. Many saw Kishi’s subsequent attempt to push the treaty through the Diet as being timed to coordinate with Eisenhower’s visit. If Kishi hoped to have the treaty ratified by late June, it would have to pass the lower house of the Diet by late May. According to law, if the treaty passed the lower house, it would automatically be ratified one month later without having to pass through the upper house, so long as the Diet remained in session. Thus Kishi calculated that if he could get the treaty through the lower house by May 19, it would automatically be ratified one month later.

On May 19 the opposition parties in the Diet used all kinds of tactics to delay the parliamentary process, including eventually blockading the speaker inside his office so that he could not reach the podium to call a vote. In order to restore enough order to pass a vote to extend the Diet session, conservative party leaders resorted to calling the police into the Diet building to remove opposition party members. The police picked up members of the opposition four to a man, and physically carried them out of the building one by one. With all the opposition members gone, the conservatives easily passed a resolution to extend the Diet session for one month, and then, within a matter of minutes, voted to pass the revised security treaty. The treaty was then set to become law one month later, so long as the Diet stayed in session.

The high-handed approach to the passage of the treaty, which seemed to demonstrate Kishi’s contempt for the democratic system, sparked a massive upsurge of popular disapproval. The Communist and Socialist Parties began a boycott of the Diet the next day, and headlines in the newspapers declared that the conservatives had passed the treaty “unilaterally.” [18] Even some members of the ruling Conservative Party who had been unaware of Kishi’s plan were shocked by his tactics. [19] Kishi’s actions widened the issue of Anpo so that it now became not only a question of peace, autonomy, and Japan’s place in the world, but also a challenge to Japan’s democracy.

| |

|

| |

Hamaya’s account of the Anpo protests begins on May 20, the day after the ruling conservatives pushed the revised security treaty through the Diet. Here students clash with police. Hamaya’s caption describes this as part of a protest action organized by the People’s Council, which “encircled the Diet and cried out for democracy.”

[anp7102]

|

|

|

To understand the hopes and fears that fueled the Anpo protests, it is helpful to concentrate on the figure of the prime minister himself. Kishi often appeared in effigy, and calls for him to resign were some of the most common messages on protestors’ signs. To understand the hopes and fears that fueled the Anpo protests, it is helpful to concentrate on the figure of the prime minister himself. Kishi often appeared in effigy, and calls for him to resign were some of the most common messages on protestors’ signs. |

Calls for Prime Minister Kishi’s resignation were among the most common protest messages. Here the phrase “Out Kishi!” has been scrawled on the outer wall of his official residence. Calls for Prime Minister Kishi’s resignation were among the most common protest messages. Here the phrase “Out Kishi!” has been scrawled on the outer wall of his official residence.

[anp7146]

|

| |

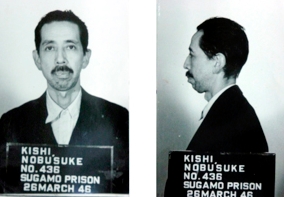

There was a reason for the concentration of anger around Kishi; he had a history with which most people in Japan in 1960 did not want to identify. Born in 1896 to an elite former samurai family, Kishi entered government in the 1920s, and rose quickly through the ranks to become the minister of commerce and industry during the war. As a member of General and Prime Minister Tōjō Hideki’s cabinet, he had signed the declaration that opened the Pacific War. When the war ended in defeat, Kishi was purged along with other wartime leaders by order of SCAP. He was subsequently imprisoned as a suspected “class-A” war criminal at Sugamo Prison but never indicted or brought to trial, as cold-war concerns led U.S. authorities to abandon the prosecution of war crimes after 1948.

The fact that a suspected war criminal would become prime minister in 1957, less than a decade after being released from prison, enraged those who wanted to believe Japan had turned a corner after the end of the war. His actions on May 19 only served to heighten people’s anger and fear, forcing them to face the uncomfortable possibility that Japan had not come so far from its wartime past.

|

|

| |

Kishi’s Controversial Journey

Much of the rage of demonstrators in Tokyo in mid 1960 was personally directed at Prime Minister Kishi Nobusuke, whose heavy-handed tactics pushing treaty renewal through Japan’s parliament were seen as doubly onerous and ominous. On the one hand, Kishi’s actions threatened Japan’s fragile postwar democracy. On the other hand, they were a reminder of his influential role in promoting Japan’s recent aggression and oppression in Asia.

Although U.S. occupation authorities arrested Kishi as an accused war criminal in 1946 and incarcerated him in Sugamo Prison, he was released from prison in 1948 without being indicted. He returned to politics in 1952 as soon as the U.S. occupation ended, was elected to the Diet in 1953, and became prime minister as head of the recently formed Liberal Democratic Party in 1957.

|

|

|

| |

Kishi (indicated by circle) as a newly appointed member of the war cabinet of Prime Minister Tōjō Hideki, October 1941. He served as minister of commerce and industry until the end of the war in 1945.

|

|

Kishi’s “mug shot” after he was arrested by U.S. occupation authorities and incarcerated in Sugamo Prison along with other accused and indicted Japanese war criminals. Kishi’s “mug shot” after he was arrested by U.S. occupation authorities and incarcerated in Sugamo Prison along with other accused and indicted Japanese war criminals. |

|

|

President Dwight Eisenhower looks on as Kishi signs the draft revised security treaty in Washington on January 19, 1960. The month-long demonstrations that convulsed Tokyo beginning on May 20 erupted after Kishi summoned the police to remove obstreperous opposition politicians and rammed this new treaty through the Diet on May 19. President Dwight Eisenhower looks on as Kishi signs the draft revised security treaty in Washington on January 19, 1960. The month-long demonstrations that convulsed Tokyo beginning on May 20 erupted after Kishi summoned the police to remove obstreperous opposition politicians and rammed this new treaty through the Diet on May 19. |

| |

Opponents of the treaty frequently attacked Kishi personally. One sign in this crowd of protestors tells Kishi to “Go Back to Sugamo.” Another sign (at bottom, center) uses the emphatic katakana script to voice a more primal feeling: “I Hate Kishi.”

[anp7025]

|

|

|

Protestors flaunt a grotesque likeness of Kishi’s impaled head sticking out a double tongue—symbolic of both his duplicitous “forked tongue” and his more general ominous image in the eyes of the protestors. He was sometimes referred to as the “monster” or “ghost” (yōkai) of the Showa era. [20] Protestors flaunt a grotesque likeness of Kishi’s impaled head sticking out a double tongue—symbolic of both his duplicitous “forked tongue” and his more general ominous image in the eyes of the protestors. He was sometimes referred to as the “monster” or “ghost” (yōkai) of the Showa era. [20]

[anp7103]

|

| |

In addition to rearmament, Kishi’s administration seemed intent on bringing back other aspects of the wartime state. In 1956, a major reform to education law reestablished centralized control over school curricula, and in 1958 Kishi attempted, but failed, to pass a reform to police law that would have given police wide powers to carry out preventative detention. Against this background, Kishi’s decision to pass the controversial new security treaty by having opposition members forcibly removed from the Diet sent a shockwave through the country. One leading progressive intellectual at the time, Tsurumi Shunsuke, declared that the struggle over Anpo was nothing less than a battle between two nations: that of prewar and that of postwar Japan. [21]

Beyond the signs held by protestors and beyond the figure of Kishi himself, we can see the specter of prewar Japan in some of Hamaya’s portrayals of the police. They are often photographed behind barbed wire barricades or in formation, their riot helmets giving them a paramilitary appearance. In one of his most iconic images, Hamaya shoots from behind police lines, capturing the confrontation between the uniform mass of helmets and a varied group of protesters, whose individual faces are all clearly visible. It centers on one man shouting at the impassive mass of police, the voice of one person against an armed, organized, and apparently indifferent state force.

|

|

| |

Protestors confront police on June 3, 1960. This iconic print, seen in full as the signature graphic for this unit, is shown here slightly cropped (top and bottom) by Hamaya himself. His composition establishes just the right intermediary scale; we can imagine the crowd of police and protestors extending far beyond the frame, but we're brought back to focus on one man.

[anp7025] |

|

|