|

| |

In May and June of 1960 Japan was rocked by some of the largest protests in its history. They erupted over the passage of a revised security treaty between Japan and the United States, titled the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security (Sōgo Kyōryoku Oyobi Anzen Hoshō Jōyaku), and have become known as the “Anpo” protests from the Japanese shorthand for that treaty. Hundreds of thousands of people came onto the streets day after day, ten million signed petitions against the treaty, thousands were injured, and one person was killed. The protests forced cancellation of a planned visit to Japan by President Dwight D. Eisenhower, toppled the conservative prime minister Kishi Nobusuke, and have come to be recognized as the most significant political crisis of the postwar period.

This unit introduces photographs taken at the peak of the Anpo protests by photographer Hamaya Hiroshi. Sympathetic to the protestors, Hamaya’s photographs allow us to see a great deal about the long-simmering tensions the postwar military alliance with the U.S. engendered within Japan. Since 1951, when it was first signed, the security treaty had been harshly criticized by those who saw it as exposing Japan to unnecessary dangers in the cold war while undermining the principles of peace and democracy. The prospect of the treaty’s revision and renewal pitted a conservative government, intent on protecting the alliance, against a loose coalition of opposition forces whose aspiration was that Japan become a neutral and unarmed nation—a decisive break with U.S. cold-war policy, and with its own militarist past.

Hamaya, a well-established freelance photographer, was the author of a number of photo books. Soon after the 1960 protests, he became the first Japanese contributor to the Magnum Photos collective. [1] As a subject, the protests are an outlier in his oeuvre, which is otherwise dominated by nature photography and ethnographic studies of life in Japan’s hinterlands. Hamaya’s interest in Anpo was driven primarily by an awareness of the momentousness of the events and a personal sympathy with the aims of the protests. His photographic record begins May 20 and ends on June 22, covering the period when the protests were at their height. It is estimated he took 2,600 photos altogether, which he narrowed down to 203 in preparation for publication as a book. This selection was narrowed further to 138 pictures, and the resulting book—titled Ikari to kanashimi no kiroku (A Record of Rage and Grief)—was published by Kawade Shobō Shinsha in August 1960. Some of Hamaya’s photographs were also published in the French news magazine Paris Match and the Japanese photography journal Camera Mainichi. This unit draws from the pool of 203 photographs.

|

|

| |

COLD-WAR JAPAN

World War II ended in disaster for Japan. The final year of the war saw relentless air raids that destroyed 40% of urban areas and culminated in the dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. With Japan’s surrender in August 1945, its vast Asian empire—once spanning from Manchuria to Indonesia—ceased to exist, and Japan itself was left destitute and in ruins. Occupation of the defeated nation began within weeks. Although the occupation was nominally carried out under the aegis of the victorious Allied Powers, in practice it was almost wholly an American affair, with the “supreme commander,” as General Douglas MacArthur was fittingly titled, given “all powers necessary … to carry out … the occupation and control of Japan.” [2]

At first, the occupation was fired by the ambitious and idealistic goals of demilitarizing and democratizing Japan. The project went well beyond dismantling the state’s war-making capacity to envision a thorough remaking of government, industry, and civil institutions so that the sources of Japan’s military aggressiveness would be removed at their very roots. The occupation authority, known as SCAP (Supreme Command of the Allied Powers) quickly dissolved the Imperial Army and Navy, issued a civil-rights directive and abolished the notorious Special Higher Police, passed a new Trade Union Law to protect workers’ right to organize, initiated a radical land-reform that would end rural tenancy, and introduced a purge of wartime leaders and ultranationalists that eventually removed 200,000 people from public office.

By 1947, occupation reforms had touched virtually every area of Japanese government and daily life, transforming the criminal and civil codes, liberating women from patriarchal family law, remaking the structure of public education, and decentralizing governing authority to foster greater local autonomy. The capstone of the drive towards democratization and demilitarization was the new Japanese constitution that came into force in 1947. Drafted by a group of occupation officials after the revisions proposed by Japanese conservative leaders were judged to be too tepid, the 1947 constitution was a model of democratic idealism, more progressive in many ways than the U.S.’s own constitution. It stated explicitly that all people would be equal before the law regardless of “race, creed, sex, social status, or family origin.” It established a right to work and to education. And most famously, in article nine it forever renounced “war as a sovereign right of the nation.”

But the ardor of this commitment to democracy and demilitarization soon faded. By 1947 the cold war dominated U.S. strategic thinking, and the U.S. began to back away from its initial burst of progressive reform in a tectonic shift that has since become known as the “reverse course.” If the intent of the early occupation had been to dismantle the military, economic, and political structures that had made militarism possible, the overarching priority after 1947 became stabilizing Japan politically and economically in the face of the perceived communist threat.

The U.S. now saw Japan as an indispensable link in a defensive chain around East Asia that stretched from the Aleutian Islands, through Japan and Okinawa, to Guam, the Philippines, and South East Asia. As such it became unthinkable that Japan might fall to communism, either through outside attack or domestic insurrection. Social stability and economic reconstruction were to be achieved at all costs, and the new strategic imperative displaced many of the early occupation reforms. The plan to dismantle Japan’s war machine by breaking up powerful concentrations of economic influence barely got off the ground before being scuttled. Of the 325 companies originally slated for possible break-up, by 1948 only 11 were ordered to split, leaving Japanese industry and finance largely unchanged from the war. [3]

The backing for a strong labor movement was also abandoned. The first year of the occupation had witnessed the growth of a spirited and confrontational labor movement which in some instances even took to locking managers out and taking over production. But SCAP made a highly public split with such radical movements in February 1947, when General MacArthur threatened to use occupation troops to put down a long-planned general strike if labor leaders insisted on going forward with it. Labor duly backed down.

| |

|

| |

On August 19, 1948, Japanese police backed by U.S. military personnel, tanks, and surveillance aircraft arrived at the Toho film studios to evict striking workers who had been occupying the buildings as part of a long-running labor dispute. In the face of this show of force the union vacated the studio without a clash. It is one episode emblematic of the reverse course in occupation policy.

Photograph provided courtesy of Nihon Dokyumento Firumu |

|

| |

By 1949 the global situation was growing more dire and the reverse course intensified. Communist forces in China overwhelmed the Nationalists to establish the People’s Republic in 1949, while the Soviet Union conducted its first nuclear-bomb test in the same year. The Korean War erupted in June 1950, pitting the Soviet-supported regime in the north against the U.S.-supported Korean government in the south—drawing the U.S. into the conflict immediately, and China soon thereafter, in December.

In this milieu, U.S. willingness to sacrifice democratic reforms in Japan in the name of security became more pronounced. 1949 saw the beginning of a “depurge,” in which the wartime leaders who had formerly been expelled from public life began to be allowed to return. In the same year, a parallel “red purge” began in which public employees suspected of leftist leanings were summarily removed from office. The purge spread to the private sector in 1950, removing a total of 22,000 people—mostly union activists—from their jobs.

The drive to rationalize the Japanese economy proceeded apace under the stern directorship of newly arrived Detroit banker Joseph Dodge. In the name of rationalization, the so-called “Dodge line” reinvigorated Japan’s largest enterprises—the same ones that had been the main engines of its wartime economy—and encouraged recentralization of economic decision-making. Even article nine’s renunciation of war became an impediment to U.S. interests. Only four years after imposing the “peace constitution,” U.S. planners found themselves pressuring Japan to allow U.S. bases to remain on its soil and to rearm, so that it could begin to participate actively in regional security. Indeed, the U.S. began to see these as conditions for ending the occupation.

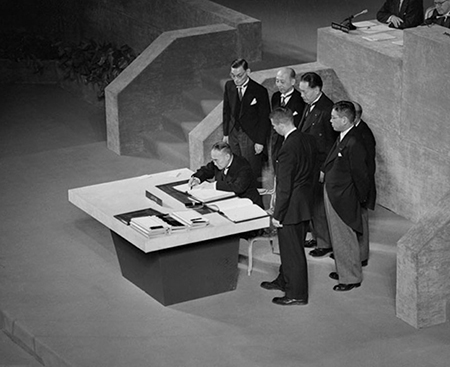

It was against this background that the Allied occupation formally and finally came to an end. The Treaty of Peace with Japan, popularly known as the San Francisco Peace Treaty, was signed by Japan and 47 other nations in September 1951, laying out the terms, widely regarded as generous, for Japan to resume sovereignty in 1952. Only a few hours later on the same day, however, Japan signed a second, bilateral security treaty with the United States. This established the terms of a continued military alliance between the two countries, and locked Japan firmly within the orbit of U.S. cold-war strategy.

|

|

Japanese Prime Minister Yoshida Shigeru signs the San Francisco Peace Treaty on September 8, 1951. 47 other countries also signed the treaty. Japanese Prime Minister Yoshida Shigeru signs the San Francisco Peace Treaty on September 8, 1951. 47 other countries also signed the treaty. |

|

|

A smaller gathering later the same day, when the separate, bilateral U.S.-Japan security treaty was signed. A smaller gathering later the same day, when the separate, bilateral U.S.-Japan security treaty was signed. |

| |

The terms of the two treaties reflected ongoing U.S. anxieties about the spread of communism in East Asia. The Treaty of Peace excluded key countries, including some of Japan’s most significant neighbors and former enemies. The Soviet Union, Korea, India, and—perhaps most importantly—China were not signatories. Both the Soviet Union and India refused to sign because of objections to the way the attached bilateral security treaty absorbed Japan into the U.S. imperium. Korea and China weren’t invited to the peace conference at all because of disagreement about who should represent them: Korea being in the midst of a civil war, and China split between the People’s Republic of China on the mainland and the Republic of China on Taiwan. Japan would soon sign a bilateral peace agreement with Taiwan, but was forced to not establish relations with the mainland as a condition for passage of the peace treaty through the U.S. Senate. The shadow cast by U.S. policy thus limited Japanese autonomy in making peace with former enemies, and establishing foreign relations.

The security treaty was widely regarded as the price that Japan had to pay in order to regain sovereignty. Yoshida Shigeru, the conservative prime minister who negotiated the treaty, understood many of the U.S. demands as non-negotiable: such was U.S. military interest in Japan that had he not agreed to them, the end of the occupation could have been postponed indefinitely. The treaty gave the U.S. the right to maintain military bases in Japan, and Japan was forbidden to grant bases to any third party without prior consultation. When Japan resumed sovereignty in April 1952, 260,000 U.S. servicemen remained in the country, stationed at 2,824 separate facilities. [4]

There was no timetable for their departure. The Ryūkyū islands, including Okinawa, were excluded from the treaty and were to remain under U.S. military occupation, also indefinitely, in what Edwin Reischauer, ambassador to Japan in the early 1960s, later characterized as “the only ‘semi-colonial’ territory created in Asia since the war.” [5]

|

|

|

| |

The unpopularity of the bilateral U.S.-Japan security treaty found dramatic expression in violent May Day demonstrations in Tokyo on May 1, 1952—just days after the occupation of Japan formally ended. Known as “Bloody May Day,” these protests left two protestors dead and 22 with gunshot wounds. Over 2,000 police and protestors were injured. Protests against the ongoing U.S. military presence in Japan continued throughout the decade. |

|

| |

Among other things, the security treaty provided that the U.S. could use its military to put down disturbances within Japan, reflecting the widely held fear on the U.S. side that Japan’s own people might drive it towards communism. Finally, the preamble to the treaty voiced the “expectation” that Japan would assume more responsibility for its own defense, meaning in effect that article nine of the constitution would have to be amended or worked around. At the time of the signing, American officials foresaw Japan creating an army of 325,000 to 350,000 within three years. This represented an enormous expansion, larger than the Japanese Self-Defense Force would ever become in the postwar period. It was only on this final point, Japanese rearmament, that Prime Minister Yoshida had some success resisting U.S. pressure.

Japan was supposed to have emerged from the peace negotiations as an independent state, but the terms of the security treaty were so unbalanced that people referred to it as an “unequal treaty,” while the situation in which it left Japan was similarly described as “dependent independence” or “subordinate independence.” A startling 40% of respondents in a September 1952 Asahi Newspaper poll reported there were times they felt Japan was not an independent country, and the most common reason given was the presence of foreign troops. Only 18% of the respondents said they believed unreservedly that Japan was independent. [6]

The security treaty was criticized across the political spectrum in Japan, but its most profound effect was to deepen and exacerbate the already deep divide between the political left and right. The political right accepted the overall framework of an anti-communist alliance with the U.S. Their criticisms focused on specific aspects of the treaty such as the lack of an explicit time frame for its revision, the provision that U.S. troops could act to quell domestic disturbances, and the fact that the treaty did not specifically obligate the U.S. to defend Japan. Regarding the expectation that Japan would rearm, Yoshida was aware of the Japanese people’s deep aversion to risking another war, and successfully resisted the precipitous rearmament envisioned by the U.S. Yoshida also saw little reason for the forced isolation from mainland China, believing the Chinese posed no real threat and should be Japan’s most natural trading partners.

Even people further to the right than Yoshida saw need for revision. Kishi Nobusuke, the former accused (but not indicted) war criminal who became prime minister in 1957 and was in office at the time of the Anpo protests, had no reservations about Japanese rearmament. To the contrary, Kishi saw rearmament as a necessary step to Japan becoming a full member of the international order and assuming equality in its relationship with the U.S. For conservatives, therefore, the limits on Japan’s autonomy, the provision on domestic disturbances, the lack of an explicit time frame, and the lack of overall parity between the two parties were the sources of dissatisfaction with the treaty.

Among Japan’s left-wing opposition, objection to the treaty was more fundamental. It was not simply the problem of parity, but a rejection of the wisdom and necessity of the treaty’s most basic tenet—the military alliance with the United States—that underlay their dissatisfaction. To a range of groupings from communists to socialists to progressive public intellectuals, Japan did not have to choose either the Soviets or the U.S., but could exist as a neutral nation. Such a position would necessitate making peace with all of Japan’s neighbors, avoiding bilateral military pacts, forbidding military bases on Japanese soil, and following the letter and spirit of article nine by refusing rearmament.

The Socialist Party settled on these as its four “Principles of Peace” between 1949 and 1951, and similar ideas were endorsed by a large group of highly respected and influential intellectuals known as the Peace Problems Symposium (Heiwa Mondai Danwakai). In a series of articles published in the mass-circulation monthly Sekai (World), this group spelled out the dangers of a separate peace and overreliance on the United States while arguing for a policy of strict unarmed non-alignment under the protection of the United Nations. The basic security argument was this: the bilateral relationship and U.S. bases in Japan put Japan in great danger in the event that the U.S. got into a war. Japan could be sucked into the conflict and potentially become a target of (nuclear) retaliation. Maintaining neutrality was ultimately safer for Japan.

This criticism of the alliance, moreover, went beyond security to include concerns about internal politics as well as broader ones about Japan’s identity and direction. To those on the left, the security treaty represented a dangerous backslide towards militarism, authoritarianism, and war—a mere half decade or so after Japan’s last prolonged and disastrous experience with these.

The ideals of peace and democracy could not be separated easily. The reverse course, initiated by the occupation and taken up with gusto by a succession of conservative governments, entailed Japan’s remilitarization both literally and economically. Only one month after the beginning of the Korean War, Prime Minister Yoshida inaugurated a modestly named National Police Reserve (Kokka Keisatsu Yobitai), a 75,000-strong force trained by U.S. advisors and armed with U.S. weaponry, including M1 rifles, machine guns, mortars, bazookas, flame throwers, artillery, and tanks (known as “special vehicles”). [7]

The Korean War also rekindled Japan’s military industrial capacity. The economic windfall brought about by “special procurement” contracts with the U.S. gave such a critical boost to Japan’s languishing economy that Yoshida and other conservatives referred to the war as a “gift from the gods.” The sudden rise in the demand for military goods reanimated Japan’s factories and economic structures and fostered closer relations between government and large industries.

|

|

Because of the constitution’s article nine, the naming of Japan’s postwar armed forces was a sensitive issue. When Prime Minister Yoshida inaugurated the force in 1950 it was called the National Police Reserve (Kokka Keisatsu Yobitai). In 1952 it was renamed the National Safety Forces (Hōantai), and in 1954 it became the Self Defense Forces (Jieitai). Here the Hōantai march in Tokyo’s downtown shopping area, the Ginza, in October 1952. Because of the constitution’s article nine, the naming of Japan’s postwar armed forces was a sensitive issue. When Prime Minister Yoshida inaugurated the force in 1950 it was called the National Police Reserve (Kokka Keisatsu Yobitai). In 1952 it was renamed the National Safety Forces (Hōantai), and in 1954 it became the Self Defense Forces (Jieitai). Here the Hōantai march in Tokyo’s downtown shopping area, the Ginza, in October 1952.

From the Mainichi Shimbun

|

|

| |

Remilitarization went hand in hand with a conservative push to “correct the excesses” of the early occupation by rolling back democratic reforms. In autumn 1951, almost simultaneously with the San Francisco Peace Conference, Yoshida presented legislation titled the Subversive Activities Prevention Law that was designed to protect Japanese society from subversion after the end of the occupation. The law would have outlawed strikes, regulated public gatherings, and instituted a press code. Fierce opposition from the left eventually gutted the law of most of its provisions, but the battle over it was only the first in a series of many similar confrontations over the coming decade.

Across the decade of the 1950s, family law and women’s rights, centralization of the school system and curricula, the extent of police powers and civil liberties, and of course the relationship with the United States were all occasions for bitter clashes between consecutive conservative governments and a shifting coalition of opposition groups that drew from the Socialist and Communist Parties, unions, women’s groups, students, and leading intellectuals. It would not be going too far to say that these battles were for the soul of Japan, waged between conservatives—who saw the occupation reforms as overzealous, and hoped to return to a system closer to that of wartime—and those who embraced the progressive ideals of neutrality, peace, and democracy, and wished to make them the foundation of a new nation that had made a decisive break with its militarist past. The 1960 Anpo protests were by far the largest of these ongoing confrontations.

Although the Socialist and Communist Parties, along with influential progressive intellectuals, were the most visible leaders of the peace and democracy movements of the 1950s, one must not overlook the extent to which these ideals tapped broad sympathy on the part of the Japanese public. Article nine, for instance, enjoyed a plurality of support through most of the postwar period, including substantial majorities of 60 to 90% from the 1960s to the 1980s. Peace movements were tremendously vibrant at the grassroots. [8] Workers, women, and students had particular prominence in these movements, and their thinking and action reveal how the broad ideals of peace and democracy were brought down to the level of everyday life.

For workers, the event that most forcefully brought the international situation together with everyday labor issues was the Korean War. Workers in the factories that supplied the U.S. war effort were faced with the uncomfortable reality that their livelihood was directly connected with a war in a neighboring Asian country, a scant five years after Japan’s own misadventures in Korea and Asia had come to an end. One 18-year-old worker who found work at a munitions plant after a long period of unemployment was forced to quit after two weeks of sleepless nights, unable to bear the thought that he was producing bullets that would kill Koreans. [9]

The war boom, although good for the economy as a whole, also went hand in hand with crackdowns on union organizers and dramatic increases in workload. This conjunction radicalized many unions and made the security relationship with the U.S. an issue of concern. The Japanese longshoremen’s union (Zenkōwan) was one of the few to defy an occupation ban and go on strike in protest of their workers’ forced participation in the war effort. They accused the U.S. of carrying out a “war of aggression” in Korea and connected their struggle for better working conditions with the fight against “the conspiracy of international imperialists, rearmament, war, and colonial policy.” [10] This was when unions began to call their first “political” strikes, meaning strikes that had political—rather than work-related—goals.

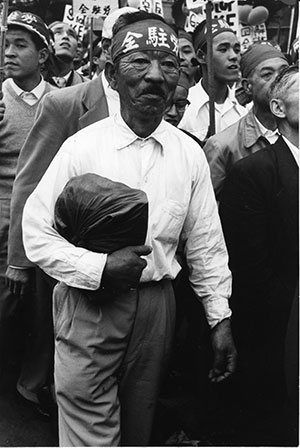

Three general strikes held in June 1960 as part of the Anpo protests were all strikes of this kind, carried out to topple the Kishi government and block passage of the revised security treaty. The largest, on June 22, involved 6.2 million workers according to Sōhyō (Japan’s General Council of Trade Unions), and was one of the largest strikes in Japanese history. [11]

|

|

|

A member of the All Japan Garrison Forces Labor Union (Zen Chūryūgun Rōdō Kumiai, or Zenchūrō) participating in a protest in front of the American embassy on June 11, 1960. This union united Japanese workers who worked in a variety of support functions at U.S. bases. A member of the All Japan Garrison Forces Labor Union (Zen Chūryūgun Rōdō Kumiai, or Zenchūrō) participating in a protest in front of the American embassy on June 11, 1960. This union united Japanese workers who worked in a variety of support functions at U.S. bases.

[anp7142] |

| |

June 22, 1960. Striking rail workers sit on an idle train in a yard in Tokyo. The signs attached to the side of the car read “Against Anpo,” one of the most common slogans of the protest. The general strike on June 22 was the third strike that month. It involved 6.2 million workers and shut down the trunk line running from Tokyo to Osaka for the first time in history.

[anp7192] |

|

| |

Women entered the peace movement in large numbers in response to an incident that occurred in 1954. In March of that year a Japanese tuna fishing vessel named the Lucky Dragon #5 was caught in the radioactive fallout from a U.S. hydrogen bomb test in the Pacific, resulting in the death of one crew member from radiation sickness. News that the ship’s cargo had been distributed to markets around Japan created a scare about the safety of the food supply, and six U.S. bomb tests over the subsequent two-and-a-half months kept the fear alive. The incident was sometimes referred to as Japan’s third nuclear bombing, and brought Japan’s continuing exposure to the gathering nuclear arms race to public consciousness. It sparked signature campaigns demanding a ban on nuclear weapons that began at the local level, led primarily by housewives who stood at their local markets or used connections with the PTA and local governments to circulate petitions.

The politicization of women in these movements often hinged on their identity as caregiver and protector of the family. The danger that first brought the issue home was contaminated fish, but this subsequently broadened into the danger of being caught up in another war. Opposing war for the sake of one’s children struck a chord with huge numbers of housewives who had lived through the devastation of World War II, and what began as a grassroots initiative quickly grew into Japan’s largest anti-nuclear movement, the Japan Council Against A- and H- Bombs (Gensuibaku Kinshi Nihon Kyōgikai, or Gensuikyō). By August 1955, just over a year after its birth, the movement had gathered nearly 32.4 million signatures against the bomb—roughly one third of the Japanese population at the time. [12] Gensuikyō, as well as dozens of women’s organizations, were major constituents of the Anpo protests.

|

|

|

| |

A farmer, part of a group from Nagano Prefecture, participates in a protest in front of the American embassy on June 11, 1960.

[anp7140] |

|

| |

Protestors from Shizuoka Prefecture join

demonstrations in Tokyo on June 11.

[anp7138] |

|

| |

Families with children participate in a rally on June 18. One child has a message attached to him that speaks in the child’s voice. Though part of the sign is obscured it probably reads something like “I hate war” (Boku wa sensō ga iya da). Many parents were politicized around the security treaty issue through their role as protectors of their children. For the people demonstrating here, the Anpo treaty was taken to be a threat to the safety of their families.

[anp7049] |

|

| |

Students are a final group who played a pivotal role in the 1960 Anpo demonstrations. Zengakuren (Zen Nihon Gakusei Jichikai Sōrengō, or All Japan League of Self-Governing Student Associations) was the most important network of student activists. After forming in 1948 out of a movement to resist U.S. “imperialism” in reforming the university system, it would remain a formidable bastion of anti-American sentiment and left-wing politics throughout the postwar.

Zengakuren students tended towards radical views and direct action. They lent moral and physical support to struggles across the 1950s including the red purges, the Korean War, and anti-U.S. base movements. The conflict over the proposed runway extension at the Tachikawa airbase near Tokyo was the most dramatic of these. Local farmers protecting their fields—pitted against the weight of Japanese officialdom carrying out the demands of the U.S. bases—came to serve as symbolic stand-ins for Japan: condensations of an enduring injustice whereby American military expansionism, assisted by Japanese authorities, preyed on local communities. Students and radical union members clashed with police many times as part of these struggles, as they would again during the Anpo protests. [13]

|

|

| |

Student Opposition

Students were among the most radical participants in the Anpo protests, leading them to frequent violent confrontations with the police. The following three photos depict an incident on June 3, when a group of a few thousand Zengakuren students broke into the prime minister’s official residence.

A photographer standing on the wall as he records the scene mirrors Hamaya’s own angle of vision—a “looking down from above” perspective that characterizes many of his depictions of the demonstrations.

|

|

| |

[anp7109] (with detail of a photographer highlighted)

|

|

| |

In a fateful moment on June 15, students stormed the south gate of the Diet (parliament) building, eventually forcing their way in. Here they are met with police water cannon.

|

|

|

| |

War memory was a key ingredient in grassroots opposition to the security treaty. The final years of World War II had brought the horror of war home to Japan, witnessed the first use of atomic weapons, and ended with the country destitute, ruined, and occupied. The awareness of shared suffering during the war had a tendency to blind Japanese public discourse to the suffering its own empire had inflicted on others, but by the same token it generated a keen focus on the disaster awaiting Japan were it to get dragged into another war.

The unpredictable perils of the cold war were lent terrifying reality by the shadow of World War II; the nuclear brinkmanship of the 1950s sent regular ripples of anxiety through Japanese society each time the precariousness of its position was exposed. Support for neutrality, as opposed to alliance with the U.S., grew stronger through the 1950s. In 1950, 22% of those polled supported neutrality, with 55% supporting the U.S.-Japan alliance. In 1953, the figures were 38% and 35% respectively, and by 1959 support for neutrality had risen to 50%, while only 26% of respondents supported the military alliance. In 1960, on the eve of the Anpo protests, 59% supported neutrality and only 14% expressed support for the military alliance. [14]

Though they were diverse and difficult to summarize, a general observation can be made about these popular engagements with peace and democracy. While peace and democracy functioned as broad ideals, they could also become local and often nationalist when people imagined their relevance to their daily lives. Workers saw their position in society as being tied up with the reconstruction of Japanese industry under U.S. military hegemony, women were motivated by a desire to protect and sustain their family’s way of life, while students were fired by out-and-out anti-Americanism and disgust at Japan’s conservative leaders.

The movements built an understanding of peace and democracy as things that had real consequences in the context of daily life, and tended towards action within that context. One of the great achievements of Hamaya Hiroshi’s documentation of the Anpo protests is to give us sustained access to the protests as they played out at that level, across the faces and lives of ordinary people for whom peace and democracy were a complex mixture of the high-minded and concrete, calling forth aspirations and anxieties that embraced the global while remaining highly local, even intimate.

|

|

| |

|

|

|