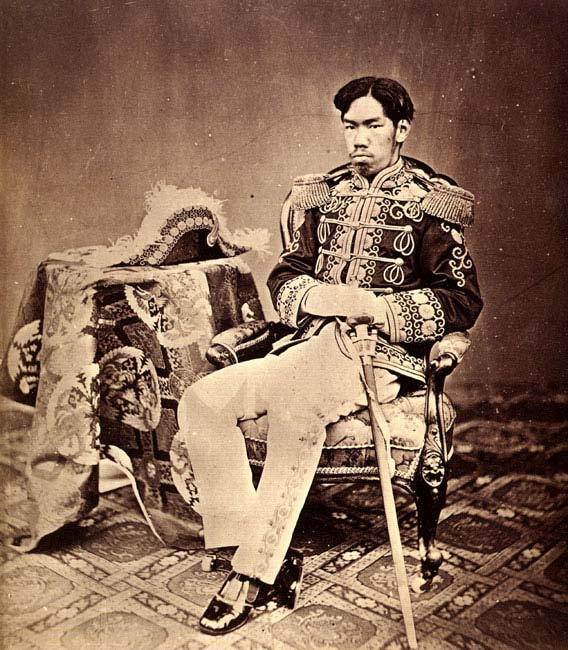

Portrait of Meiji emperor, photograph by Uchida Kyuichi, 1873

[toa5000]

Portrait of Meiji empress, photograph by Uchida Kyuichi, 1873

[toa5001]

Everything about this imperial family portrait emphasizes the symbolic role of the imperial family in leading Japan on the path of “Westernization”—the clothing, headgear, furniture, tablecloth, Western-style bouquet of flowers. At the same time, this is mixed with unmistakably Japanese artwork in the background. The imperial couple’s son would later reign as the Taisho emperor from 1912 to 1926. Here and in other prints, the emperor and his family were never actually identified explicitly on the artwork itself, although their identity was obvious.

“A Mirror of Japanese Nobility” by Toyohara Chikanobu, August 1887

[2000.548]

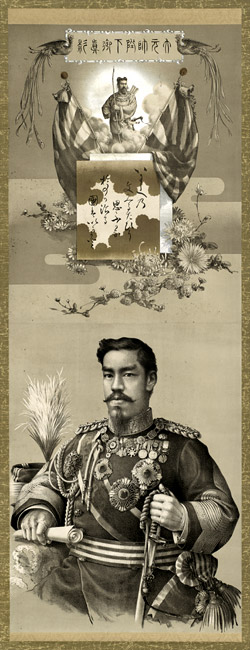

This realistic portrait of the emperor in Western-style military uniform, sometimes wrongly thought to be a photograph or based on a photo, is a lithograph, dating from around 1889, based on an 1887 drawing by the Italian Edoardo Chiossone. The elaborate artwork above the sovereign’s head is an excellent example of the mythologizing that accompanied this nationalistic “reinvention of tradition.” It mixes military flags with a representation of “Emperor Jimmu,” the divine progenitor who was supposed to have descended directly from Amaterasu, the sun goddess, and established the imperial line in Japan in 660 B.C.

“True Portrait of His Majesty,” lithograph based on

a drawing by Edoardo Chiossone, ca. 1889 [2000.547]

This print captures the more traditional side of the imperial family’s symbolic role, with the emperor and his consort relaxing in a pavilion in a beautiful private garden and viewing the autumn maple leaves. Mt. Fuji is visible in the distance. As always in these prints, the sovereign and his wife are dressed in formal Western clothes, as are the males in attendance. Female attendants wear traditional court dress. Although the pavilion is classically Asian, reflecting the enduring influence of Chinese architecture on Japan, everyone is seated on Western chairs.

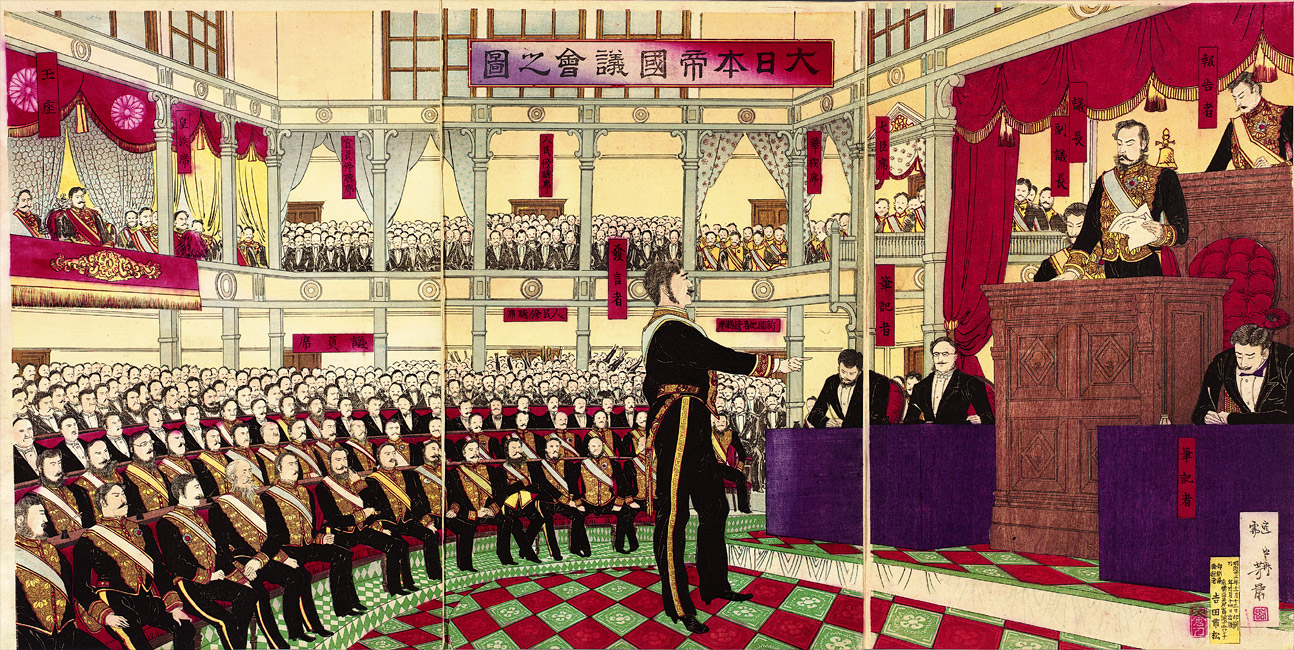

The convening of a diet, or parliament, under the new Meiji Constitution in1890 was hailed in Europe and the United States as a sign of Japan’s impressive “Westernization.” Although property requirements restricted the electorate in the lower house to a small number at the outset, by 1925 the diet had approved universal male suffrage. (Japanese women did not get the vote until 1946.) In this depiction of the new diet, the emperor overlooks the scene from a box on the balcony on the far left. Government officials and elected diet members all wear formal Western-style dress.

The Meiji Constitution of 1890 was “bestowed” on the government by the emperor, and established a constitutional monarchy strongly influenced by German legal models. While the constitution declared the emperor to be “sacred and inviolable,” it also laid the basis for parliamentary government and eventually the emergence of political parties.

The Meiji Constitution of 1890 was “bestowed” on the government by the emperor, and established a constitutional monarchy strongly influenced by German legal models. While the constitution declared the emperor to be “sacred and inviolable,” it also laid the basis for parliamentary government and eventually the emergence of political parties.

“Maple Leaves at New Palace,” artist unknown, December 1888

[2000.237]

"Illustration of the Ceremony Promulgating the Constitution,” Artist unknown, 1890

[2000.226]

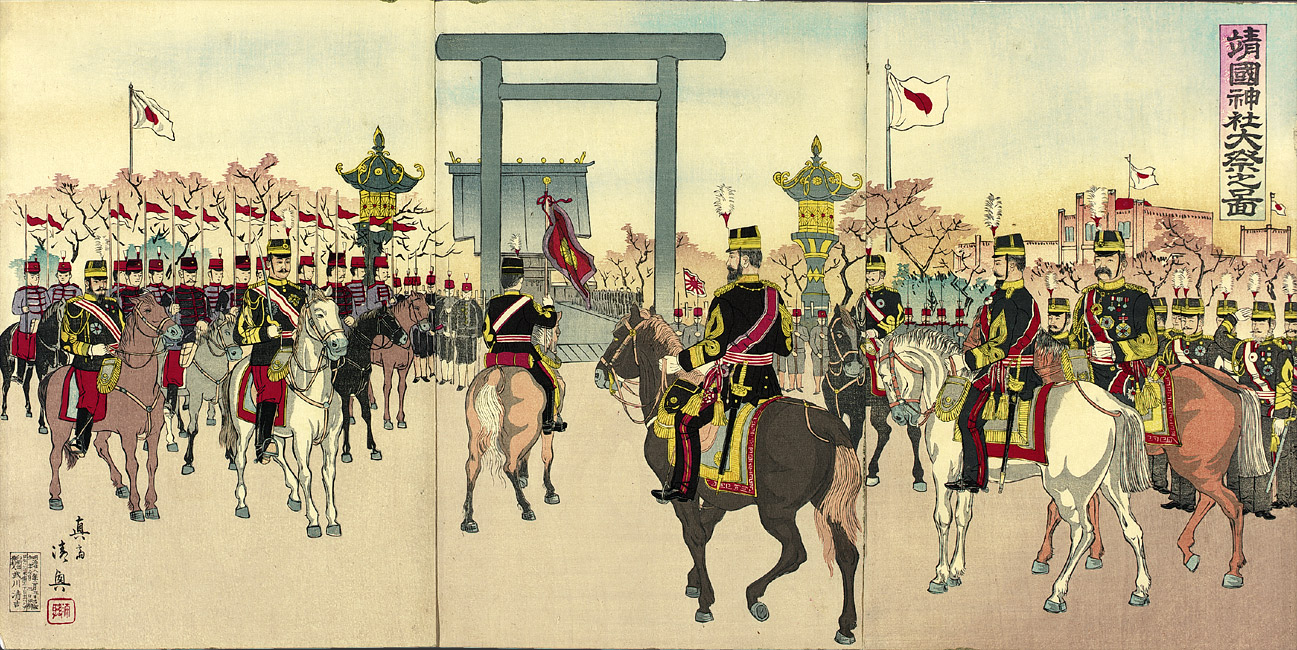

Central to the creation of the modern emperor system was the carefully promoted association of the emperor with the indigenous Shinto religion, and this in turn with the creation of a militarily strong modern nation-state. A key step in this direction was the establishment of the Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo, where the souls of those who died fighting for the imperial cause beginning in the 1850s were enshrined. The huge bronze torii or gateway at Yasukuni was erected in 1887. Yasukuni became a major symbol of Japanese patriotism in the Asia-Pacific War of the 1930s and early 1940s, and remains a focus today for paying respect to Japanese who died in World War Two.

“Illustration of the Imperial Diet of Japan” by Gotÿ Yoshikage, 1890

[2000.535]

Beginning in the mid 1880s, the Meiji emperor’s role as supreme commander was given greater and greater public emphasis, as Japan girded to prove itself equal to the Western powers in the great game of imperialist conquest. This concerted effort to create a “rich nation, strong military” culminated in victory over China in 1895 and over Tsarist Russia in 1905. As usual, woodblock prints such as these emphasized the Western-style uniforms and discipline of the Japanese forces.

“Illustration of Grand Festival at Yasukuni Shrine” by Shinohara Kiyooki, 1895

[2000.513]

“Observance by His Imperial Majesty of the Military Maneuvers of Combined

Army and Navy Forces” by Toyohara Chikanobu, 1890 [2000.499]

“Illustration of a Military Review” by Toyohara Chikanobu, 1887

[2000.247]

The pioneer Japanese photographer Uchida Kyuichi took these rare formal portraits of the Meiji emperor and his consort in 1873 and 1872 respectively.

Scroll right...

The Meiji Constitution of 1890 was “bestowed” on the government by the emperor, and established a constitutional monarchy strongly influenced by German legal models. While the constitution declared the emperor to be “sacred and inviolable,” it also laid the basis for parliamentary government and eventually the emergence of political parties.

The Meiji Constitution of 1890 was “bestowed” on the government by the emperor, and established a constitutional monarchy strongly influenced by German legal models. While the constitution declared the emperor to be “sacred and inviolable,” it also laid the basis for parliamentary government and eventually the emergence of political parties.