| |

PROTEST & PROFITS

The pages of The Tokyo Riot Graphic did not present a detached and disinterested record of events. This publication was typical of the press of this era both in using popular interest in the riot (or war) to extend its commercial reach and in presenting images that implicitly approved and celebrated such acts of protest, arguably helping to incite future actions.

|

|

The inside-front and back covers of this special issue are filled with ads for other newly launched ventures of the Kinji Gahō Company. Small- to medium-sized ads pushed sets of “postcards of beautiful women” or the writings of Kunikida and Yano. A larger ad promoted The Lady’s Graphic (Fujin Gahō), a magazine founded just two months earlier (and still published today). The inside-front and back covers of this special issue are filled with ads for other newly launched ventures of the Kinji Gahō Company. Small- to medium-sized ads pushed sets of “postcards of beautiful women” or the writings of Kunikida and Yano. A larger ad promoted The Lady’s Graphic (Fujin Gahō), a magazine founded just two months earlier (and still published today). |

|

Advertisements inside the front and back covers of the special riot issue promote a variety of other periodicals published by the same company.

Advertisements inside the front and back covers of the special riot issue promote a variety of other periodicals published by the same company.

Inside-back cover

with an ad for The Lady’s Graphic (marked in red)

[trg039] |

| |

|

The Tokyo Riot Graphic also ran a prominent advertisement for the inaugural issues of two graphic magazines respectively aimed at educationally ambitious boys and girls (or their parents): Graphic Knowledge for Youth (Shōnen Chishiki Gahō) and Graphic Knowledge for Young Girls (Shōjo Chishiki Gahō). The ad promised stories on “Japanese, Chinese, and Western history” as well as information on flora and fauna of the natural world. The two publications were merged in 1906. It is not clear how long this venture survived, but the genre of illustrated educational magazines for children has enjoyed a long and profitable life through the present.

The Tokyo Riot Graphic also ran a prominent advertisement for the inaugural issues of two graphic magazines respectively aimed at educationally ambitious boys and girls (or their parents): Graphic Knowledge for Youth (Shōnen Chishiki Gahō) and Graphic Knowledge for Young Girls (Shōjo Chishiki Gahō). The ad promised stories on “Japanese, Chinese, and Western history” as well as information on flora and fauna of the natural world. The two publications were merged in 1906. It is not clear how long this venture survived, but the genre of illustrated educational magazines for children has enjoyed a long and profitable life through the present.

|

Inside-front cover with ads for Graphic Knowledge for Youth and Graphic Knowledge for Young Girls (marked in red)

Inside-front cover with ads for Graphic Knowledge for Youth and Graphic Knowledge for Young Girls (marked in red)

[trg001] |

| |

In choosing this moment to launch magazines for women, young boys, and young girls, Yano and Kunikida clearly expected the booming popularity of The Wartime Graphic would help them reach new audiences. In choosing this moment to launch magazines for women, young boys, and young girls, Yano and Kunikida clearly expected the booming popularity of The Wartime Graphic would help them reach new audiences.

The editors of The Tokyo Riot Graphic explicitly referenced the new role of print media in promoting modern political awareness and action on the one hand, even as they evoked traditional customs on the other hand. A good example of the former is the woodcut of streetcar passengers reading a leaflet announcing the anti-peace-treaty rally.

|  |

Illustrations such as the depiction of streetcar passengers reading leaflets announcing a rally subtly promoted political activism by both men and women. Illustrations such as the depiction of streetcar passengers reading leaflets announcing a rally subtly promoted political activism by both men and women.

[trg028]

|

| |

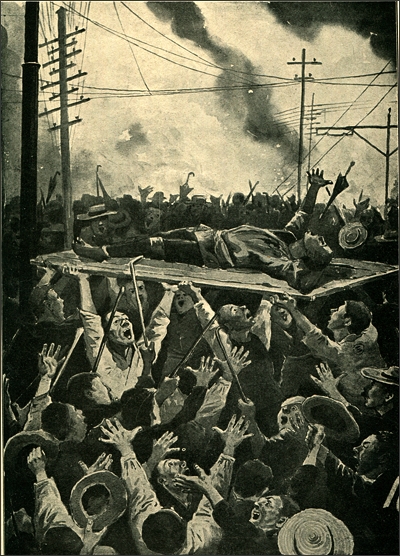

The adroit tapping of tradition can be seen in an illustration of anguished rioters carrying a victim on a wooden door repurposed as a stretcher, a graphic that appears to simultaneously celebrate the riot and lament the harm people suffered in its course. The Japanese caption to this illustration uses a folk religious metaphor, likening the scene complete with shouts of “wasshoi, wasshoi” to Shinto festivals where crowds of celebrants carried portable shrines through the streets with this same chant.

|

|

|   Rioters carry an injured protester on a makeshift stretcher. The caption tells us that they shouted chants commonly associated with carrying portable Shinto shrines on festival days.

Rioters carry an injured protester on a makeshift stretcher. The caption tells us that they shouted chants commonly associated with carrying portable Shinto shrines on festival days.

English caption: “The Great Disturbances in Tokyo: Wounded persons being conveyed to a hospital on the night of Sept. 6, when eleven electric cars were burnt.

[trg019] |

| |

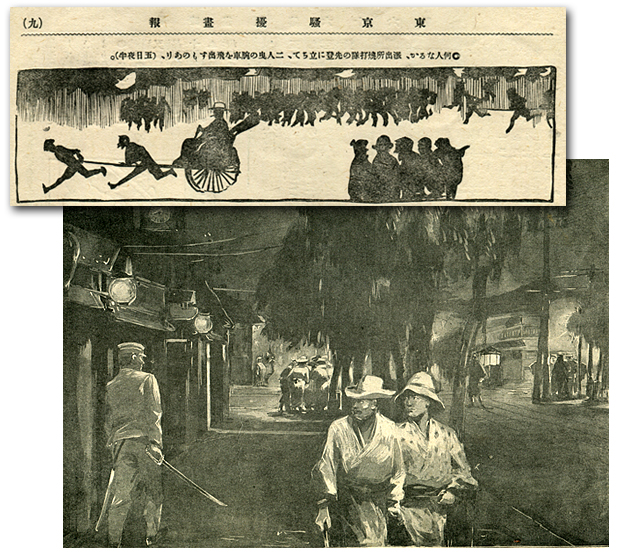

In less flamboyant images as well the magazine seems to be sensationalizing and exciting interest in the event, while of course furthering sales, by evoking intrigue, mystery, and scandalous personal behavior. A woodcut on the concluding page of Yano’s narrative asks in its caption “Who is this? At the head of a group smashing a police station is seen this man scooting away in a two-puller rickshaw (night of the 5th).” A sense of mystery is conjured as well by a darkly shaded illustration of what the caption calls the “awe-inspiring scene” on the night of September 5 of the “entirely deserted” Ginza district, normally “the most flourishing quarter of the city.” As with the images of riot, the dark tones of this illustration carry forward the style developed by these artists in their depictions of the war in earlier issues of the magazine. These illustrations also evoke the contemporaneous prints of Kiyochika as well as the brooding feel of some of Hiroshige’s famous early-19th-century landscapes.

|

|

|

| |

Mystery and intrigue are conveyed in graphics like the above, depicting rickshaw pullers rushing a mysterious figure away from rioters destroying a police box, and the eerily deserted Ginza district, emptied of its usual nighttime pleasure seekers.

English caption: “The Great Disturbances in Tokyo: On the night of September 5 when the disturbances took place, the Street of Ginza, the most flourishing quarter of the city, presented an awe-inspiring scene. The street was entirely deserted, except by a few men stopping to talk in a low tone, and some policemen with drawn swords walking under dimly-lighted eaves.”

[trg036] detail, [trg011]

|

|

| |

The magazine evoked scandal with an opaquely described photograph of a modest home, described only as the “residence of Mme Okoi, who has become notorious in connection with the recent disturbances.” Who was this woman? Readers who had been following the personal life of Prime Minister Katsura as told in full-page newspaper stories in the days leading up to the riot would immediately recognize the name. Okoi was a Tokyo geisha who began a relationship with Katsura in the early days of the war.

|

|

|

Scandal entered the Hibiya Riot picture in the form of gossip about a geisha who was well known to be the mistress of the prime minister.

Scandal entered the Hibiya Riot picture in the form of gossip about a geisha who was well known to be the mistress of the prime minister.

“Residence of Mme Okoi,” image 3 from full-page spread (page 26)

|

|

English caption: “Tokyo Under Martial Law. (1) The main gate of the official residence of Count Katsura, Prime Minister. (2) The gate of his private residence. (3) Residence of Mme O-koi, who has become notorious in connection with the recent disturbances...” English caption: “Tokyo Under Martial Law. (1) The main gate of the official residence of Count Katsura, Prime Minister. (2) The gate of his private residence. (3) Residence of Mme O-koi, who has become notorious in connection with the recent disturbances...”

[trg026] |

| |

The Meiji oligarchs were famous for their womanizing ways, and in particular their patronage of geisha, but Katsura’s timing made this a particularly scandalous connection. He installed Okoi as his mistress in this residence in Akasaka in June 1905, just three months before the riot. As difficult peace negotiations dragged on over the summer, he made Okoi his frequent companion not only at her own residence but also at the prime minister’s official residence, where he spent most of his time. She thus found herself in the public eye, and the subject of sensational newspaper accounts that lambasted Katsura while describing their relationship in detail.

As the late Kuroiwa Hisako details in her fascinating recent study of the riot, most readers of such stories would have decided that Katsura was acting outrageously by taking up with such a woman during a national crisis. And Okoi herself became an object of great curiosity. She incited fury in some quarters, sympathy in others. Her most eloquent defender in the aftermath of the riot was the well-known writer Kinoshita Naoe, one of the era’s tiny but vociferous band of anti-war socialists. But during the riots crowds gathered and threatened to attack her home; she and her servants went into hiding.

In the 1920s Okoi told her side of the story in an autobiography, probably ghost written, which was initially serialized in the Asahi newspaper. [13] Women were thus present not only among the crowds at rallies and riots; as sexual companions to Japan’s rulers, they were also collateral targets, objects of scorn and celebrity. One can see Okoi as a new sort of heroine, or anti-heroine, of an emerging mass culture. Although women of the demimonde had been celebrated in the popular culture of the Edo era (in woodblock prints especially), they were rarely if ever connected in this public fashion to political scandal.

|

|

A Civilized Empire

At first glance, the cover for The Tokyo Riot Graphic is puzzling. The banner across the top depicts Tokyoites marching in orderly, if determined, fashion. These men and one woman could just as easily have been en route to a pro-government wartime victory rally as to an anti-government postwar anti-treaty rally.

|

|

Cover, with detail of Cover, with detail of

central image below

The Tokyo Riot Graphic,

No. 66, Sept. 18, 1905

[trg000] |

| |

| |

The large central image depicts a scene viewed from what appears to be the rooftop of a building, with its green parapet in the foreground. The viewer looks out upon an urban landscape of warehouses, factories and smokestacks, with what might be office or government buildings in the background (one with a flag atop it).

|

|

|

| |

The pale slivers rising from among the buildings suggest plumes of smoke. At first glance, one assumes the smoke is rising from the city’s factories. But much more likely, it is rising from the fires set by the rioters. These plumes are not actually attached to the smoke stacks; this scene is probably the view from the roof of the publisher’s office, the perch from which Kunikida and his colleagues reportedly saw “fires here and there, flames rising from 15 or 16 different spots.” [14] At most, then, the center of the magazine’s cover offers only a very indirect representation of the tumult in the city. The only direct representation of the riot on this cover is found in shadowy form on the lower edges where darkly-drawn policemen are chasing rioters. How should we understand this cover art?

I see it in part as a statement that the anti-treaty riot is taking place in a proudly industrialized and civilized nation, one which has taken its place as a world power and emerging empire. One finds scattered traces of this sentiment elsewhere in the magazine as well. The ad for The Lady’s Graphic lists six reasons to read the next issue. The first calls on women to “Look at this magazine if you want to know what women do in countries that win wars,” while another inducement is “Ten Illustrations of our Ally’s Monarchy” (no doubt a reference to the Anglo-Japanese alliance). The text of the ad for the new Graphic Knowledge magazines similarly and baldly promises to bring Japan’s youth to the level of these same places: “we will teach the children of our nation those things that the boys and girls of Europe and America learn as they grow up.”

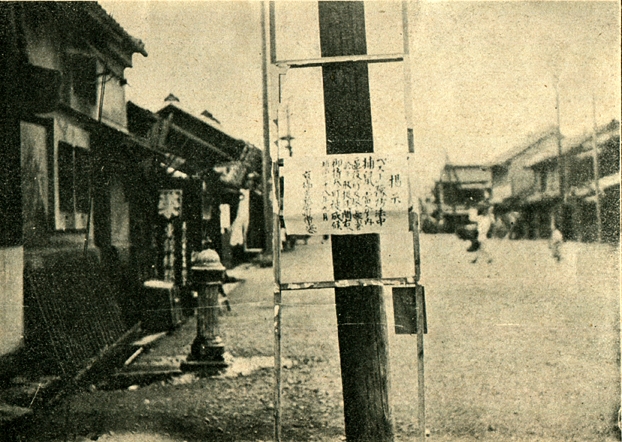

But probably the oddest photograph in the entire magazine offers the best evidence of the desire to achieve, and the anxiety at failing to sustain, Japan’s hard won place in the ranks of civilized nations. At the center of this scene of a none-too-elegant Tokyo street stands a none-too-elegantly hand-written poster. It leans against a telephone or telegraph pole. Just behind is a fire hydrant. The English caption calls this a “notice posted at various places in Tokyo concerning the purchase of rats.” The Japanese caption offers a bit more detail, explaining that “one sees this sort of poster in places all over the city explaining that due to the destruction of police boxes, the purchase of rats has been suspended.”

|

|

|

| |

Notice announces that “due to the destruction of police boxes,

the purchase of rats has been suspended.”

English caption: “Tokyo Under Martial Law. ...(4) Notice posted at various

places in Tokyo concerning the purchase of rats. (Photographs taken

on the morning of Sept. 7)”

[trg026c]

|

|

| |

Readers a century later may well find even this longer caption a puzzle, but those at the time would have understood easily. As part of the project of public health and hygiene initiated by the Meiji government nationwide—and later in the colonies—the police encouraged city dwellers to catch rats, understood by modern medicine to spread dangerous disease. As incentive, authorities offered a modest payment for each animal delivered.

The Tokyo Riot Graphic choose to include in its pages (the same page as the pictures showing police guarding the residence of Mme Okoi and the private and public residences of her lover, the prime minister!) this reminder that one project to make Japan’s capital a safe and civilized place was at least temporarily on hold. It would be up to readers to decide if the blame for this setback on the path toward civilization and world recognition rested on destructive crowds for their outburst, or on the authorities for a weak foreign policy which incited riot by betraying popular hopes for a prouder place among the nations and empires of the world. Most seem to have drawn the latter conclusion. Their actions initiated an era of continuing protest on behalf of imperial democracy.

Aftermaths

The anti-treaty riots subsided after three days (and after the imposition of martial law). An uneasy calm settled over the capital. But within six months, further acts of public protest and political violence took place in Tokyo. First from March 15 to 18, 1906 and then from September 5 through the 8th—the precise anniversary of the anti-treaty riot—protest against a proposed increase in streetcar fares began with rallies in Hibiya Park and ended with the smashing of dozens of streetcars and attacks on streetcar offices, and, in the more widespread violence of September, the destruction of police boxes, dozens of injuries, and 113 arrests. The March riots were covered in some detail in the April 1 issue of Kinji Gahō (in October 1905, with the end of the war and the battle over the terms of peace, The Wartime Graphic [Senji Gahō] reverted to this original title).

|

|

|

| |

Kinji Gahō here illustrates what its English caption calls “The Agitation in Tokyo against the Proposed Advance of the Street Electric Car Fare. On Mar. 15th a group of the agitators head by the members of the Japan Socialists headed to the head office of the Street Railway Car Co. office and there ensued some excited scene.” The involvement of the Japan’s first, and soon suppressed, socialist party foreshadows the emergence of a more formally organized social movement centered on the working class in the following decades.

[trg230] [trg229]

|

|

|

In addition to its continued chronicling and depicting of urban protests, the postwar Kinji Gahō extended its interest in social problems by venturing outside the city. Its February 1, 1906 issue, with a striking cover showing two crows or vultures hovering over three gaunt farm-dwellers, was a “Northern Japan (Tōhoku) Famine Number.” The issue featured detailed coverage of the consequences of the extremely poor harvest of the previous summer, which resulted from heavy rains and cold temperatures. |

Cover of the Feb. 1, 1906 issue of The Japanese Graphic, which was devoted to famine in northern Japan.

Cover of the Feb. 1, 1906 issue of The Japanese Graphic, which was devoted to famine in northern Japan.

[trg227]

|

| |

In the face of declining sales and significant operating losses, Yano Fumio decided to cease publication of Kinji Gahō later in 1906. Clearly issues of war and empire sold more copies than did topics of peacetime, whether those of famine and protest or scandal and celebrity. But in the following years, one continues to find in press reports occasional items which possibly served to incite protest even as the publishers offered the plausible deniability that they were cautioning against mischief. On the eve of a rally on February 11, 1908 to protest an increase in taxes, the following leaflet was both circulated in the thousands, and then printed in full in the Tokyo Mainichi Shinbun, one of the city’s major daily papers.

|

|

| |

ANTI-TAX INCREASE

PEOPLE’S RALLY

Hibiya Park, February 11, 1908

Admonitions to Attendees:

1. Do not bring any dangerous weapons

2. Do not prepare oil, matches, or clubs

3. Do not fight with the police

4. Do not smash any police boxes

5. Do not smash any streetcars

6. Do not throw stones at the Diet building

7. Do not attack pro-tax or Seiyūkai M.P.’s

|

|

| |

The style of this flyer is that of the ubiquitous Edo-era injunctions to townspeople or villagers, typically mounted on a post and planted in the ground for all to see and respect. It is noteworthy that the event was called for February 11. This was the national holiday known as kigensetsu, a date calculated by the Meiji state to represent the moment nearly 2600 years earlier when the (mythical) first emperor Jimmu ascended the throne, thus founding the nation and the imperial line. It is noteworthy that four of the nine riots in Tokyo between 1905 and 1918 took place on this date or the previous day. As a holiday, the date was convenient for rallies, but this holiday was further meaningful for connecting the people and the throne. The handbill teased the authorities even as it protected its issuers by advising against the actions most common in the riots of these years, while enumerating them in needlessly explicit detail. And by printing the flyer’s contents in full, the newspaper as well was safely complicit in reminding readers what they should not, but might indeed, undertake. In the event, a modest riot did take place in the wake of the rally, in which 11 streetcars were stoned and 21 people arrested.

The similar illustrations, the identical rally location, identical actions and targets, and the repetitive dates of these various protests make the case for viewing them as related incidents rather than spontaneous or random outbursts. In the decade following the 1905 anti-treaty riot, organizers and crowds were quite clearly acting in a sequel to a political theater first staged in that September. The celebration of the 1905 events in the illustrated press played its part in preparing the ground for these repeated movements of protest.

|

|

| |

|

|

|