| |

DEMOCRACY & THE CROWD

It is the wide range of loosely connected issues and targets going well beyond simple nationalism and support of empire which justifies seeing in the Hibiya Riots the germination of a drive to realize democracy as well as empire. The illustrations help us see this. Given that the peace treaty was negotiated on the Japanese side in Portsmouth by the foreign minister, Komura Jutarō, the government naturally feared attacks on the foreign ministry. After martial law was declared on September 6, army troops were stationed to guard possible targets, including Foreign Minister Komura’s official residence.

|

|

| |

Army troops guard the foreign minister’s official

residence after martial law was declared.

English caption: “Tokyo Under Martial Law: At midnight of Sept. 6 martial law was proclaimed in Tokyo....(1) Front of the entrance to the official residence of the Minister of Foreign Affairs....(Photographs taken on the afternoon of Sept. 7).

[trg008 detail]

|

|

| |

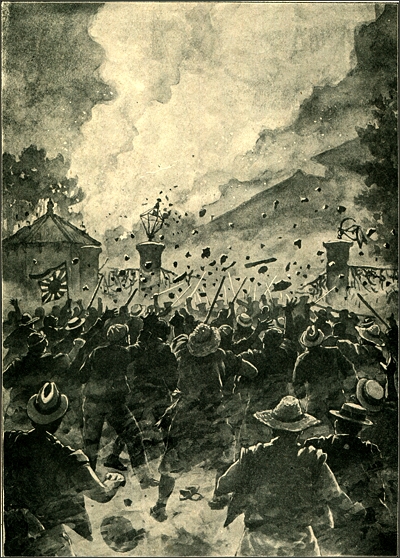

Yet neither the ministry itself, nor the minister’s residence, was subject to a major attack. Rather, and at first glance quite illogically, it was the official residence of the minister of home affairs which became the most important government office to be stormed by a massive angry crowd during the riot.

|

|

This illustration of “tens of thousands” of rioters attacking the official residence of the minister of home affairs on September 5 is the most famous and widely reproduced image in The Tokyo Riot Graphic. This illustration of “tens of thousands” of rioters attacking the official residence of the minister of home affairs on September 5 is the most famous and widely reproduced image in The Tokyo Riot Graphic.

English caption: “The Great Disturbances in Tokyo: Riotous scene presented on the evening of Sept. 5, in front of the main gate of the official residence of the Home Minister, which was set fire to by the infuriated mob.”

[trg009] |

|

| |

Located literally across the street from Hibiya Park, the home minister’s residence was certainly a convenient target. But the foreign ministry itself was only one block more distant. A crowd said to number “tens of thousands” made the home minister’s official residence an object of particular fury not simply for its proximity, but rather because this minister stood at the apex of the state agency most responsible for restricting the activities of the people. These restrictions were manifest in the formally political senses of suppressing freedom of assembly and freedom of expression. The nation’s police, including those in Tokyo who had banned the rally, were an arm of the home ministry, and the ministry oversaw censorship of the press. The ministry’s presence, and that of its police force, was also felt in a more general intrusion into people’s daily lives. Yoshikawa Morikuni, one of Japan’s first generation of socialists active in the early-20th century, witnessed what he described as an aged “rickshaw-puller type” ask one of the rioters to “by all means burn the Ochanomizu police box for me, because it is giving me trouble all the time about my household register.” [11]

As an agency within the home ministry, the police were thus logical targets of the crowd whether for their role in banning assemblies or for bothering people about their more ordinary obligations to the state. They were also easy targets. Modeled on the Paris police of the late-19th century, Tokyo’s police (and the police around the country as well) were dispersed throughout the city in so-called “police boxes” (kōban), small stations typically manned by two officers, with a desk in a front room open to the street for easy observation and communication with residents, and a back room for sleeping. When officers cultivated trust with the neighborhood, the system of ubiquitous boxes provided effective community policing. But when trust broke down, the scattered police boxes were defenseless in the face of attacks by large crowds. The rioters destroyed nearly three quarters of all the boxes in the city. The Tokyo Riot Graphic prominently placed a dramatic illustration of one such attack on its inside cover page, along with photographs of two demolished boxes.

|

|

| |

Attacking the Police

The police suffered around 450 casualties in the Hibiya Riot, and symbols of their authoritarian power became major targets of the crowd’s wrath. Several police stations were set on fire, and close to three quarters of the small two-man “police boxes” scattered throughout metropolitan Tokyo were demolished.

|

|

|

English caption: “The Great Disturbances in Tokyo: The Shitaya police-station burning on the night of Sept. 5.”

[trg023] |

English caption: “The Great Disturbances in Tokyo: The upper picture—debris of the burnt branch Kyobashi police-station. The lower picture—debris of the burnt police-box near Kyobashi. (Photographs taken on the afternoon of Sept. 6)” English caption: “The Great Disturbances in Tokyo: The upper picture—debris of the burnt branch Kyobashi police-station. The lower picture—debris of the burnt police-box near Kyobashi. (Photographs taken on the afternoon of Sept. 6)”

[trg014] |

|

|

English caption: “The Great Disturbances in Tokyo: Scene of a police-box being set fire to by rioters.”

[trg004 detail] |

English caption: “The Great Disturbances in Tokyo: The upper picture—debris of the branch police-station at Ogawamachi, Kanda, which was wrecked on the night of Sept. 6; and was burned down on during the following night. The lower picture—debris of a burnt police-box. (Photographs taken on the afternoon of Sept. 7)” English caption: “The Great Disturbances in Tokyo: The upper picture—debris of the branch police-station at Ogawamachi, Kanda, which was wrecked on the night of Sept. 6; and was burned down on during the following night. The lower picture—debris of a burnt police-box. (Photographs taken on the afternoon of Sept. 7)”

[trg024] |

|

| |

With others, editor Kunikida saw this destruction as portentous. As he gazed at fires burning around the city center from the roof of the building that housed the editorial offices, he is reported to have mused to a colleague that “I wonder if a revolution has actually started?” [12] Kunikida selected illustrations to convey this volatile and violent situation to readers which figuratively brought the war back home; their composition and feel drew on artistic tropes already developed in illustrations sent back from the war zone by the Graphic’s artists over the previous 18 months.

Other targets during this and the later riots provoked enmity for their role in support of the bureaucratic state and its allies in the political parties. These included pro-government newspapers as well as politicians and their parties. The politician targeted most often was Hara Takashi, the home minister at the time of the Hibiya Riot, and his Seiyūkai Party was a repeated target of popular fury as well.

One further target was the city’s streetcars and the company that ran them, attacked in the 1905 riot and two smaller incidents the following year (one on the anniversary of the Hibiya Riot) for both economic and political reasons. The streetcars were relatively new, having begun service in 1903, the same year that Hibiya Park opened. They were expensive for ordinary Tokyoites. They threatened the livelihood of the city’s many thousands of rickshaw pullers, who were numerous among the rioters and those arrested. Streetcar passengers had been subject to the transport tax to finance the war, at the rate of one sen per ride added to the base fare of three sen. And rumors abounded that the service was initiated thanks to a sweet deal struck among Home Minister Hara, members of his party in the Tokyo city council, and the streetcar company itself. All three parties were criticized for having profited at the expense of ordinary people.

|

|

|

In addition to targeting the symbols of police authority, the crowd also vented its anger against streetcars and the company that ran them. It was widely believed that fares were too high and the company had profited from the war.

In addition to targeting the symbols of police authority, the crowd also vented its anger against streetcars and the company that ran them. It was widely believed that fares were too high and the company had profited from the war.

English caption: “The Great Disturbances in Tokyo: Electric cars burning on the night of Sept. 6”

[trg015] |

English caption: “The Great Disturbances in Tokyo: On the night of Sept. 6, the branch office of the Tokyo Street Railway Co. and eleven electric cars were burnt by rioters. The upper picture—scene of the office after the fire. The lower picture—debris of the burnt cars.”

English caption: “The Great Disturbances in Tokyo: On the night of Sept. 6, the branch office of the Tokyo Street Railway Co. and eleven electric cars were burnt by rioters. The upper picture—scene of the office after the fire. The lower picture—debris of the burnt cars.”

[trg025] |

|

| |

In sum, these ferocious and lavishly illustrated attacks were not random. Nor were their targets directly connected to the issue of empire at the political forefront of the day. The crowd targeted those seen to suppress people’s freedom of assembly and expression, as well as those seen to impose economic hardship and be shadily connected to the home ministry and the political allies of its leader. Attacks on the home minister, his police, and the streetcars evinced a populist and democratic, if also a violent, spirit.

|

|

| |

The War at Home

The Tokyo Riot Graphic concludes with a lengthy written account of the protest by Yano Ryūkei, the co-editor, interspersed with dramatic line drawings. The wide mass audience that the magazine was targeting can be seen in the inclusion of phonetic syllables (furigana) next to every single ideograph. This made it possible for people with even the most rudimentary education to understand what was written about how the patriotic war with Russia had abruptly turned into a populist “war at home.”

|

|

An enlarged detail of the text (right) shows the phonetic notations next to every ideographic character, which enabled readers at all levels of education to pronounce and thus recognize every word.

[trg029] |  |

|