|

| |

On September 5, 1905, a massive three-day riot erupted in Tokyo protesting the disappointing terms of the peace treaty that ended the Russo-Japanese War. A decade earlier, after emerging victorious in the Sino-Japanese War, Japan had demanded and received a huge indemnity from defeated China. Although the war with Russia was far more costly in casualties and money, both sides were exhausted by 1905 and Japan was in no position to demand an indemnity from Russia. Because the Japanese public had been bombarded with reports of victory after victory, expectations of a profitable peace settlement were high and the outrage when this did not materialize was enormous.

Almost three-quarters of the police boxes throughout the capital city were destroyed, buildings and streetcars were torched, and some 450 policemen and 50 firemen were injured in addition to many of the protesters. The government responded by declaring martial law. It almost seemed as if the war had come home.

The anti-treaty riot—commonly called the Hibiya Riot after the park where the demonstrations began—marked the first major social protest of the age of “imperial democracy” in Japan that began with the promulgation of the Meiji constitution in 1890 and extended into the early 1930s.

This unit focuses in detail on the visual record of this spontaneous anti-government demonstration as presented in The Tokyo Riot Graphic, an extraordinary special issue of an illustrated magazine that was published at the time and featured both photographs and artistic renderings of the unfolding violence.

|

|

Images in this unit, unless otherwise noted, are from a special edition of

The Japanese Graphic called The Tokyo Riot Graphic, No. 66, Sept. 18, 1905 |

|

|

| |

MAKING NEWS GRAPHIC

The founding father of illustrated newspapers and magazines worldwide was the Illustrated London News, first published in 1842 and immediately flattered by imitators throughout the West: the Leipziger Illustrirte Zeitung in Germany and L’illustration in France (both founded in 1843); and, a bit later, Harper’s Monthly (1850) and Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper (1855) in the United States. The owner and publisher of Tokyo Riot Graphic was Yano Fumio (1851–1931, also known by the pen name of Yano Ryūkei). Yano was a well known writer and political activist. He first encountered these publications, in particular the Illustrated London News and a more-recent British competitor simply titled The Graphic, while visiting England in 1884. We do not know which issues he read. But coverage of the British empire and its military engagements was a staple element of the graphic genre, and one which very likely caught his attention. Yano decided Japan both sorely lacked and very much needed publications of comparable content and quality, and he eventually undertook to address this need himself. [1]

Yano launched his venture with the title Oriental Graphic (Tōyō Gahō) in 1903. Later that year he renamed the magazine Recent Events Graphic (Kinji Gahō) and similarly named his publishing venture the Kinji Gahō Company. With the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese War in February 1904, Yano and his trusted chief editor, the well-known writer Kunikida Doppo, correctly decided that the public wanted a steady diet of wartime pictures and text. To signal their commitment to war news and images from cover to cover, with publication of the February 18 issue they re-titled the magazine The Wartime Graphic (Senji Gahō). Starting with the fourth issue under this new name (March 20, 1904), Yano and Kunikida added the English title The Japanese Graphic to the cover and English-language captions to the illustrations.

These naming innovations signaled the twin aims of offering a Japanese record of the war to an international audience and distinguishing theirs as the definitive record among several competing wartime graphic serials. Through October 1905, including nine special issues, Yano and Kunikida put out 68 numbers with this title, a rate of more than three issues per month with print runs of around 50,000 copies, before turning the magazine’s title back to the more generic Recent Events Graphic. The Russo-Japanese War not only provided the spark that set off the fire of imperial democratic protest. It brought into being the publications that captured and helped define this event in its own time and for posterity, and it published images of the war that shaped the visual record of the socially turbulent “peace” that followed.

As with the Illustrated London News and its followers in the West, the graphic genre in Japan included text in the form of articles on politics, war, and society, but it was most notable for its numerous illustrations. The earliest such periodicals in the West primarily featured drawings carved into wooden blocks through the technique of end-grain wood engraving. [2] Early photographs likewise had to be engraved into wooden blocks in order to be reproduced in newspapers or magazines. Over the course of the 19th century, new technologies (lithography and half-tone printing) allowed the transfer of photographs and hand-drawn illustrations to a printed page without need for hand engraving, although in both the West and Japan some artists and publishers continued to make use of woodblock prints. The Wartime Graphic, including the special riot issue, featured a wide array of image techniques: multi-color lithography (and in some cases possibly woodblock prints) for its striking covers, half-tone printing of both photographs and hand drawn art (primarily watercolors and pencil sketches), and woodblock prints inserted into narrative text.

|

|

| |

The Wartime Graphic: selected covers |

|

| |

As one can see from this sampling, the covers of The Wartime Graphic are remarkable

for the sophistication of the artwork and the variety of themes and moods. One of

course finds some covers with a nationalistic and martial aspect, such as that of

May 20, 1904 celebrating soldiers rushing into battle. But one also finds

relatively calm scenes, such as that of the soldiers in the woods (December 20,

1904) and even some suggesting the Japanese are carriers of peace (through war),

such as the cover showing a dove being released from a naval ship (July 10, 1904).

Also noteworthy are scenes from the homefront, including a marvelous depiction of

lanterns carried in a victory parade (July 1, 1905), and a cover highlighting the

surging popularity of postcards as a new means of communication (March 10, 1905).

The cover invoking the figure of the Sun Goddess (Dec 10, 1904) and that depicting

US-Japan friendship (Aug 10, 1905) are also of interest. This cover appeared just as

the peace-treaty negotiations were being concluded in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and

it specifically commemorated the visit to Japan of a major diplomatic mission led by

the American secretary of war, William Howard Taft, and including President

Roosevelt’s famous daughter, Alice.

|

|

|

| May 20, 1904 [trg204] |

July 10, 1904 [trg205]

|

Dec. 10, 1904 [trg209] |

| Dec. 20, 1904 [trg210] |

Mar. 10, 1905 [trg212]

|

April 20, 1905 [trg216] |

| June 20, 1905 [trg218] |

July 1, 1905 [trg219]

[Waseda University Library, Tokyo, Japan]

|

Aug. 10, 1905 [trg221] |

| |

While Yano and Kunikida were certainly pioneers of this genre in Japan, they were not in fact the first to produce illustrated newspapers or magazines in Japan along the lines of European or American predecessors. That honor belongs to the Fūzoku Gahō (Customs Graphic), founded in 1889. This fascinating publication featured illustrations on culture and customs of elites and ordinary folk alike. It was particularly concerned to contrast the daily life of the Japanese past with new modes of dress or deportment of Western origin. During the Sino-Japanese War (1894 to 1895) an illustrated monthly True Record of the Sino-Japanese War (Nisshin sensō jikki) was one of the first periodicals to feature significant numbers of half-tone photographs. The Customs Graphic also celebrated this war with a fancifully rendered battle scene on one of its covers, but it otherwise showed little concern for matters political; the True Record was published only once a month, with relatively stale photographs of ships and landscapes, or portraits of generals and admirals.

Compared to these earlier efforts, the graphic publications from the time of the Russo-Japanese War were unprecedented in the visual force of their illustrations as well as their popularity and circulation. Hiratsuka Atsushi, an assistant to Kunikida from the founding of Oriental Graphic in 1903, recalled in a 1908 memorial essay about the great writer that the magazine’s sales took off when it began to run illustrations sent by artists dispatched by Kunikida to Korea in early 1904. Hiratsuka gives literal meaning to the cliché “hot off the presses” as he describes the frenzy of efforts to meet reader demand: “On one occasion, the printer couldn’t keep up and it is even said that the [printing] machinery caught fire.” [3]

In addition to such publications modeled on Western periodicals, one found in 19th-century Japan a vibrant and evolving indigenous tradition of woodblock-print broadsheets. Combining image and text, and focused on newsworthy incidents, the earliest of these coincidentally began to appear around the same time as the earliest publications of illustrated news in the West. Called kawaraban and circulated in spite of prohibitions issued by the Tokugawa authorities, they flourished in the early-19th century. After the Meiji Restoration, a now legal—if closely monitored—genre of broadsheet prints soared in popularity, especially during the Satsuma rebellion. Known as nishiki-e, these were single-page sheets featuring a traditionally produced woodblock print in vibrant color and a short explanatory text, usually taken from a recent newspaper article.

The woodblock prints of the Sino-Japanese War analyzed by John Dower in Throwing Off Asia ll were an outgrowth of these widely circulated “news” prints. At the time of the Sino-Japanese War, as Dower describes, they played a key role in conveying images and understandings of the war to people in Japan. But as Dower notes in Throwing Off Asia lll, the situation was quite different a decade later. Although woodblock prints during the Russo-Japanese War did offer some powerful images, many of the prints merely imitated those of the Sino-Japanese War.

During Japan’s second imperialist war, the illustrated periodical press was a source of greater creative energy than individual prints, and it found its way to a far larger reading and viewing audience. Its repertoire of images owed a debt both to the illustrated genre of the modernizing West and to this evolving indigenous practice of woodblock prints of current events. Some of the new graphic publications of the Russo-Japanese War were short-lived commercial failures, but others, prominently including The Japanese Graphic, were both popular and profitable. They featured art work of high quality produced by some of Japan’s most talented young artists. Leading contributors to The Japanese Graphic during and after the war included Koyama Shōtarō, one of the most important early teachers of Western art in Japan, and the most promising students of his Fudōsha Academy.

Whereas 2,000 to 5,000 copies might have been made of a traditional woodblock print of this era, each issue of The Japanese Graphic (and its competitors) boasted print runs of 40,000 to 50,000 copies, offering from 20 to 50 photographs and illustrations of varied sizes and types per issue. In numbers and in visual impact, these illustrated publications were the most important sources to imprint the war and its aftermath in Japanese popular imagination. Particularly significant was the hand-drawn art, both watercolor paintings and woodblock sketches, better able than the photographs of that era to convey motion and mood. While the history of politics in imperial Japan, including the story of social protest, has been much studied by historians writing in English as well as in Japanese, the visual record produced by illustrated journalism offers insights not easily gained from textual sources into a number of themes. These images make it clear that imperialism was not simply a top-down imposition of the government, but a co-production with active participation by the commercial media and its customers. They also show that even as masses of people embraced the cause of empire, they added to it their own desire for democracy.

The War at Home

The Russo-Japanese War ended with a stalemate on the battlefield. Both sides were exhausted and depleted. Japanese forces suffered roughly 80,000 fatalities (over 20,000 of them from disease), compared to some 17,000 (almost 12,000 from disease) in the Sino-Japanese War a decade earlier. The total cost of the war in yen came to 1.7 billion yen, eight times the cost of the Sino-Japanese War. To pay these bills, the government had borrowed aggressively on the London bond market and had imposed all manner of new or increased taxes at home: sales taxes on cooking oil, sugar, salt, soy sauce, sake, tobacco, and wool; and a transportation tax that raised the cost of riding on the new streetcars of the capital by 33 percent. Faced with the prospect of even greater costs if the war continued, Japanese negotiators were willing to settle for less than they desired or had implicitly promised to the home-front populace.

In the peace treaty negotiated at Portsmouth, New Hampshire through the mediation of American president Theodore Roosevelt, Japan did win a free hand to dominate Korea as a protectorate, and it gained the upper hand in Southern Manchuria in the form of a leasehold that formed the basis for the Southern Manchuria Railway, protected by troops that developed into the Kwantung Army. It also took possession of the territory of southern Sakhalin. But it gained no reparations which might have offset the war’s cost. The leasehold was a form of imperialist encroachment, to be sure, but not an outright colony, and Sakhalin was a barren place of little strategic or economic value. In contrast, the Sino-Japanese War of a decade before had brought both a massive indemnity and full control of the island of Formosa (Taiwan), which became a Japanese colony.

It is not surprising in this context that a coalition of journalists, university professors, and politicians in the Japanese diet (parliament) who had vociferously supported the war now came together to protest the peace. They turned to the urban populace for support, calling a rally in Hibiya Park on September 5. The Tokyo police—an arm of the national government administered through the powerful Home Ministry—forbad the gathering. But a crowd estimated to number around 30,000 overran the barriers and rushed into the park. A brief rally ensued, about 30 minutes in all.

|

|

|

| |

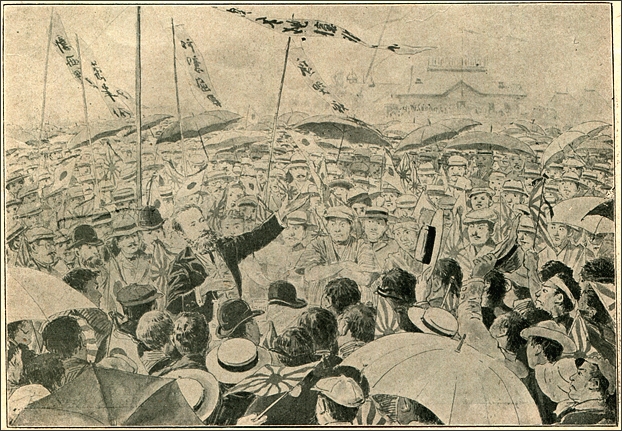

The politician Kōno Hironaka leads a crowd from Hibiya Park on a march to the Imperial Palace.

English caption: “The Great Disturbances in Tokyo: The upper picture—Mr. Kōno, ex-president of the House of Representatives, speaking at the anti-peace mass meeting of Tokyo citizens....”

[trg007a]

|

|

|

Later that day, a second large crowd gathered in front of the Shintomiza theater to hear speeches denouncing the treaty. Later that day, a second large crowd gathered in front of the Shintomiza theater to hear speeches denouncing the treaty. |

Illustration of a crowd listening to anti-treaty speeches.

Illustration of a crowd listening to anti-treaty speeches.

English caption:

“The Great Disturbances in Tokyo: Riotous scene seen on Sept. 5, near the Shintomiza theatre, where anti-peace lectures were to be given.”

[trg013] |

| |

| |

As the attendees spilled out from the initial rally in the park, Kōno Hironaka, a popular and hawkish political veteran and head of the alliance which had organized the event, led a crowd of perhaps 2,000 on a march toward the imperial palace. Others in the crowd fought with police, and the violence began to spread. Groups of dozens or hundreds attacked police and government buildings, offices of a pro-government newspaper (Kokumin shinbun), and streetcars and the offices of the streetcar company.

|

|

Map of Tokyo in 1905

[trg100]

|

| |

Source: Andrew Gordon, Labor and Imperial Democracy in Prewar Japan (Berkeley:

University of California Press, 1991)

These actions continued for three days, during which time Tokyo lacked any effective forces of order. By the time the riot ended, 17 people had been killed and 311 arrested in clashes with police or the military troops eventually sent to subdue the rioters. 70 percent of the city’s police boxes (small two-man substations located in neighborhoods through the city) were destroyed along with 15 streetcars. Smaller riots broke out in Yokohama and Kobe. Anti-treaty rallies took place nationwide. [4]

This outburst of riot and protest was the first of nine such incidents in Tokyo that took place through 1918 and were sparked by related discontents (see table, below). The illustrated record of the anti-treaty riot, discussed in the chapters to follow, teaches us much about the themes marking not only that event, but those that followed as well.

|

|

| |

Riots in Tokyo, 1905–18

The following table gives a sense of the range of incidents and the overlap of issues,

as well as the noteworthy overlap in the dates of these events and their location.

|

|

| |

Date: |

Main Issues: |

Secondary Issues: |

Site of Origin: |

Description: |

|

|

|

| |

Sept. 5-7, 1905 |

Against treaty ending

the Russo-Japanese War |

Against clique

government;

for “constitutional

government” |

Hibiya Park |

17 killed; 70 percent of police

boxes, 15 streetcars destroyed;

progovernment newspapers

attacked; 311 arrested; violence

in Kobe, Yokohama; rallies

nationwide

|

|

| |

Mar. 15-18,

1906 |

Against streetcar-fare

increase |

Against “unconstitutional”

behavior of

bureaucracy, Seiyūkai |

Hibiya Park |

Several dozen streetcars smashed;

attacks on streetcar company

offices; many arrested; increase

revoked

|

|

| |

Sept. 5-8, 1906 |

Against streetcar-fare

increase |

Against “unconstitutional”

actions |

Hibiya Park |

113 arrested, scores injured; scores

of streetcars damaged; police

boxes destroyed

|

|

| |

Feb. 11, 1908 |

Against tax increase |

|

Hibiya Park |

21 arrested; 11 streetcars stoned

|

|

| |

Feb. 10, 1913 |

For constitutional

government |

Against clique

government |

Outside Diet |

38 police boxes smashed; government

newspapers attacked;

several killed; 168 injured (110

police); 253 arrested; violence in

Kobe, Osaka, Hiroshima, Kyoto

|

|

| |

Sept. 7, 1913 |

For strong China policy |

|

Hibiya Park |

Police stoned; Foreign Ministry

stormed; representatives enter

Foreign Ministry to negotiate

|

|

| |

Feb. 10-12,

1914 |

Against naval corruption

For constitutional

government |

Against business tax

For strong China policy |

Outside Diet |

Dietmen attacked; Diet, newspapers

stormed; streetcars, police

boxes smashed; 435 arrested;

violence in Osaka

|

|

| |

Feb. 11, 1918 |

For universal suffrage |

|

Ueno Park |

Police clash with demonstrators;

19 arrested

|

|

| |

Aug. 13-16,

1918 |

Against high rice prices |

Against Terauchi

Cabinet |

Hibiya Park |

Rice seized; numerous stores

smashed; 578 arrested; incidents

nationwide |

|

|

| |

Source: Andrew Gordon, Labor and Imperial Democracy in Prewar Japan (Berkeley:

University of California Press, 1991)

|

|

|