| |

LUXURY & THRIFT IN WARTIME

So how did this “rich” cosmopolitan consumer culture fare with the rise of militarism in the 1930s and in the face of wartime scarcities, mounting governmental rationing, and anti-luxury campaigns? Images of nationalistic sentiment such as the Japanese hinomaru flag only started to appear in Shiseido publications gradually from around 1935.

|

|

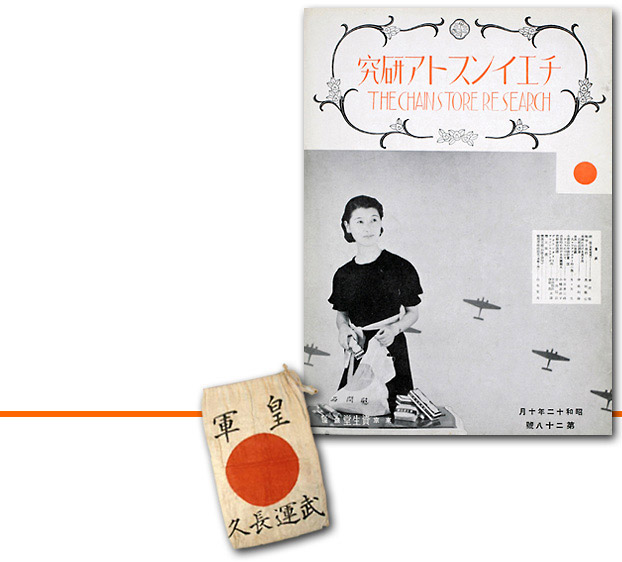

By October 1937, the year the war in China began, more overt images of wartime mobilization became evident as exemplified by the cover of that month’s The Chainstore Research that featured the image of a young wife packing up Shiseido soap bars in “comfort bags” (care packages; imon bukuro) for soldiers fighting on the continent in which the silhouettes of airplanes are visible behind her. 27 She looks confidently at Japan’s rising sun flag placed in the upper right-hand corner of the composition, which is suggestively contiguous with the journal’s masthead and visually associated by color through the use of red for both the sun and the title.

“Comfort Bag” or care

package (imon bukuro)

for soldiers, ca. 1937

[sh06_1937c_bag]

|

| |

The bag itself displays the hinomaru sun of Japan’s national flag and together with the label “comfort bag” on the bottom may have had a wartime slogan such as “eternal good luck in war” (buunchōkyū) printed on it. These comfort bags were profitable retail items that were even sold at upscale department stores like Mitsukoshi. Clearly manufacturers were interested in having their goods included as comfort items for the troops.

Two months later in December, the cover image of The Chainstore Research featured a group of women in aprons (kappogi) wearing banners for the Greater Japan Women’s National Defense Association (Dai Nihon Kokubō Fujinkai). 28 It was groups such as these that nationally spearheaded preparation and sending of comfort bags. School children were also an important part of this effort. Images of wartime nationalism in advertising were both direct and indirect: Japanese troops on the frontline were featured on the cover of the September 1939 issue of Shiseido Chainstore Alma Mater.

|

|

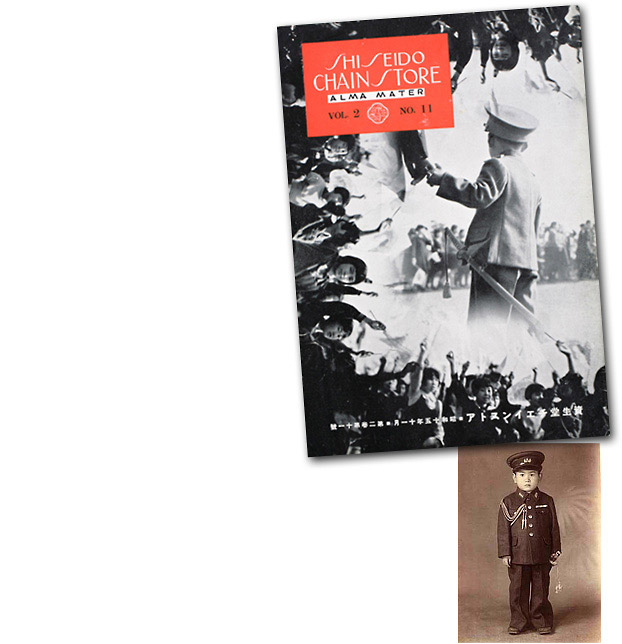

These politically reactionary images could, however, still be rendered in an experimental aesthetic idiom like montage, as seen in the cover image of the November 1940 issue of Shiseido Chainstore Alma Mater that features a border of cheering schoolchildren waving national flags surrounding the central photograph of a small boy holding his mother’s hand in a soldier’s uniform with his back to the viewer. 29 He is dressed up for the seven-five-three (shichi-go-san) rite of passage festival traditionally held in mid-November when parents prayed for their children’s health and happiness.

Shiseido Chainstore Alma Mater

vol. 2, no. 11, cover, November 1940

[sh02_CS_1940_11_1]

Although traditionally children wore kimonos for this celebration, in the wartime period boys wore military uniforms. Reinforced by the enlarged figure of the boy and his superimposition over the purposeful parade of people in the background, the image (on the Chainstore cover above) asserts the child as Japan’s national pride and the future of its military.

Child in uniform for 7-5-3 festival, Japan, ca. 1940

|

| |

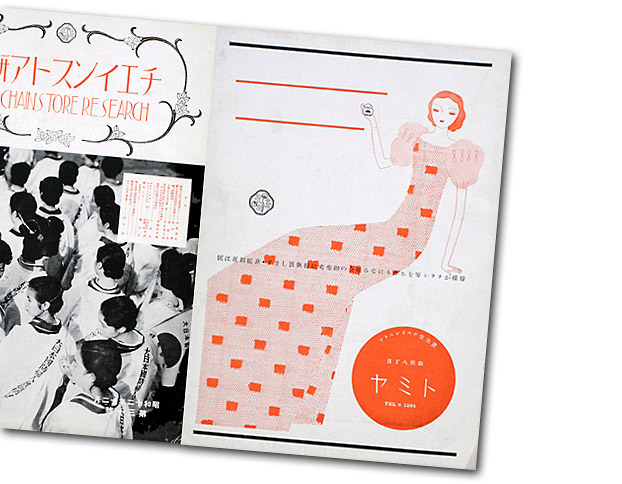

At the same time, in the same October 1937 issue discussed above, Yamana Ayao’s elegantly dressed female figure on the back cover of the journal continues the company’s image of luxury and beauty.

|

|

|

| |

In September 1938, the Japanese government issued a series of anti-luxury edicts, which was part of an effort to reduce consumption and boost household savings to support the war effort. One of the most well-known wartime slogans, “Luxury is the enemy” (zeitaku wa teki da) appeared soon after the government issued its “Regulations Restricting the Manufacture and Sale of Luxury Goods” in July 1940. 30 Yet surprisingly, until well into the war years, commercial manufacturers skillfully balanced patriotic practicality and conservation with capitalistic luxury and consumption.

Like many consumer products manufacturers, cosmetics companies faced a particular challenge during the wartime years, as they needed to straddle the line between staple good and luxury item. Shiseido did not want to abandon its hard-won deluxe brand image, but it also could not continue to promote wasteful luxury in the face of state ideological injunctions to the contrary. The selling points of health, high quality maximizing efficacy, and patriotic national production were put forward as compensatory features.

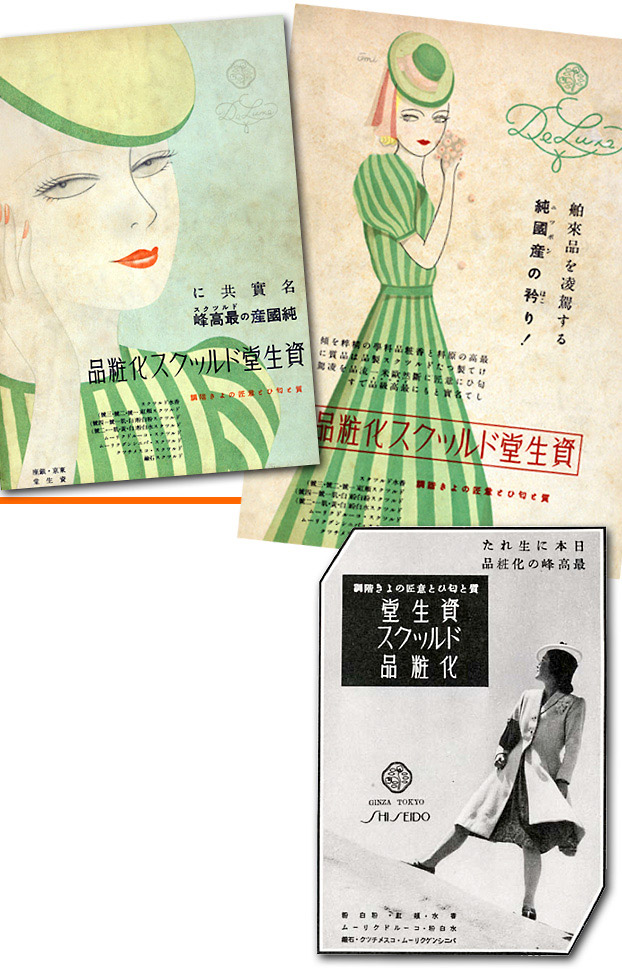

A magazine advertisement for “Shiseido Deluxe Cosmetics” that ran in the popular journal Housewife’s Companion (Fujin no Tomo) in 1940 clearly tries to have it both ways. It exhorts consumers to show their patriotism by partaking in the “pride of pure national production” (jun kokusan no hokori), with “national production” glossed in katakana as “Nippon” (Japan) to the right, that offers products superior to imported goods.

|

|

|

| |

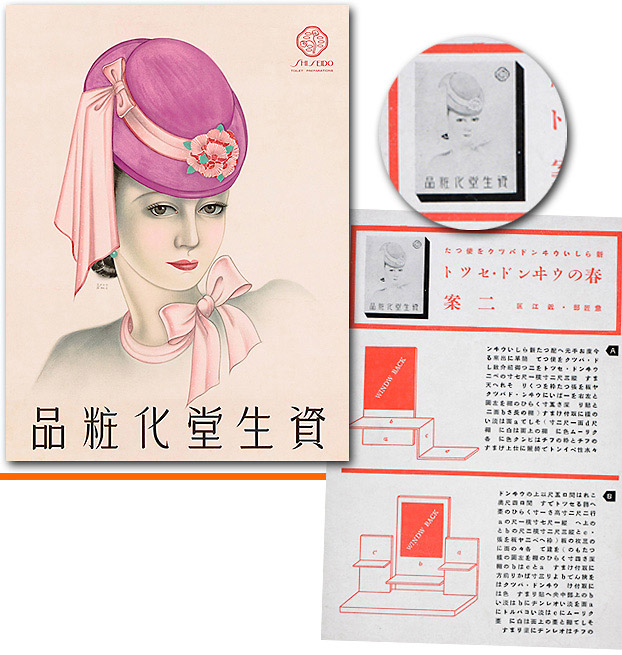

Other promotional materials took a similar approach promoting national production, deluxe quality and international style. A fashionable woman in a colorful hat and bow is featured prominently in a poster designed for a show window display. In Shiseido Chainstore Alma Mater retailers are given several options for setting up this poster as a backdrop to product display.

|

|

|

|

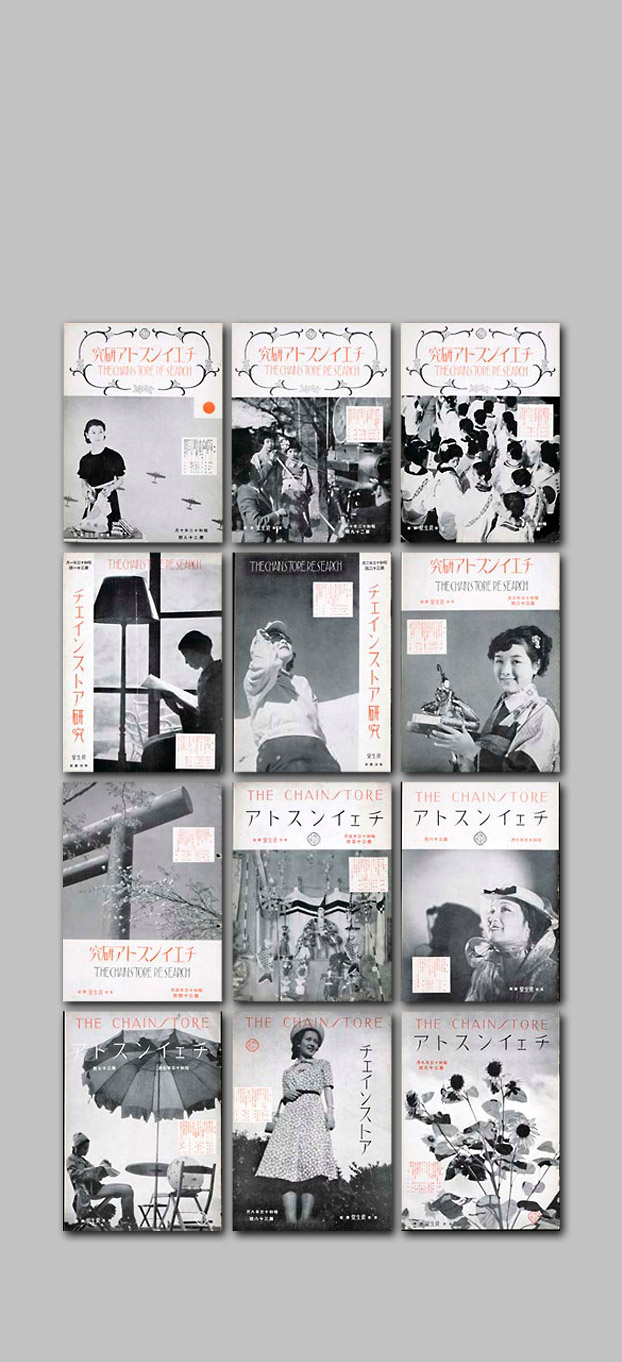

A Year of Chainstore Covers

October 1937–September 1938

Covers from Shiseido’s Chainstore between October 1937 and September 1938 show the array of subjects—from filmmaking (11/37) to homefront wartime activities (10/37 & 12/37)—the publication featured. Designs encompass both traditional and contemporary styles, and women are represented in a variety of ways: as homemakers, in patriotic wartime efforts, engaged in traditional arts, and as independent “modern” women—both glamorously cosmopolitan and down to earth. The journal title also changed over the course of the 12 months from “The Chainstore Reseach” to simply “The Chainstore.”

The Chainstore Research and The Chainstore

Shiseido publication, covers, 12 issues: October 1937–September 1938

|

| |

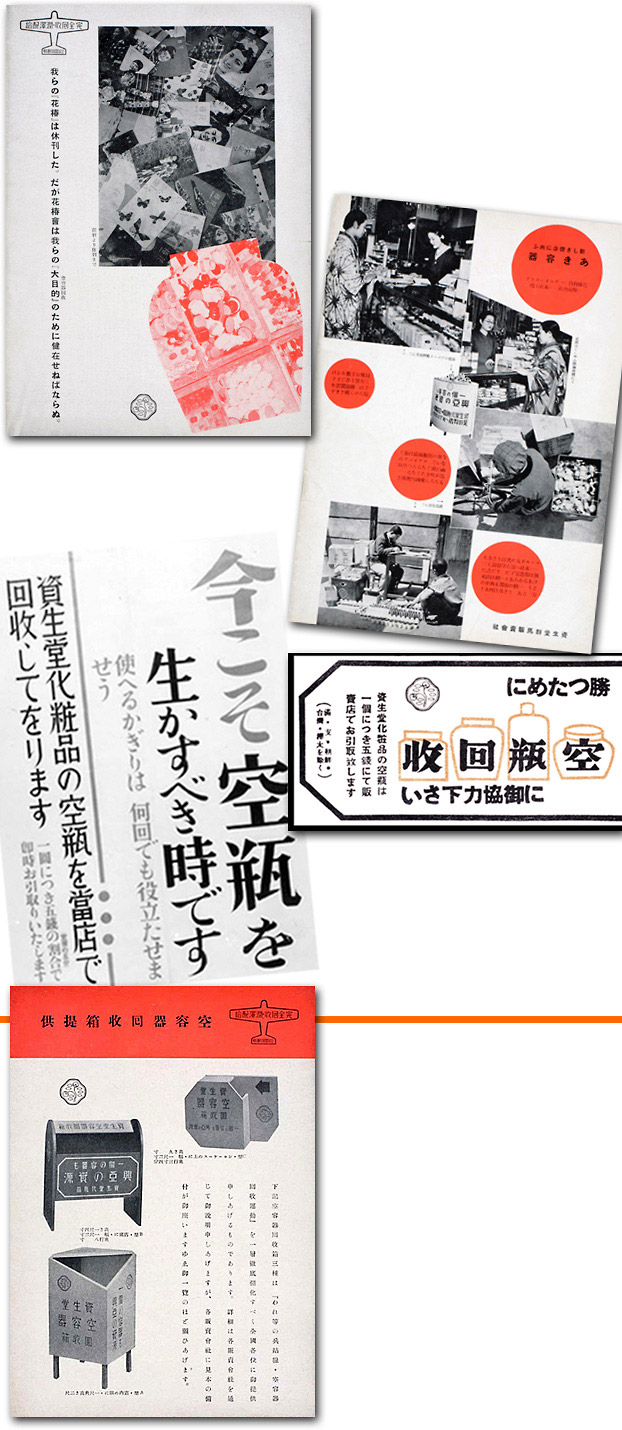

Recycling Luxury

While the term “deluxe” was still clearly in evidence in 1940, by September of that year Hanatsubaki magazine stopped publishing to conserve precious resources. For similar reasons, the company also changed its containers from glass to ceramics, cardboard, and aluminum, depending on the product. 31

|

|

Shiseido was also able to join in the mobilization effort by spearheading a consumer campaign to recycle their empty cosmetic containers.

Container recycling campaign

Shiseido Chainstore Alma Mater (left)

vol. 2, no. 9, back cover, September 1940

[sh02_CS_1940_09_2]

Empty Container recycling

ad,

1940s (above)

[sh06_1940C_1_RecyclingAd]

Empty Container recycling

poster, 1940s (left)

[sh06_1940C_3_RecyclingPoster]

Under the slogan, “Recycle empty containers for victory,” the company magazines showed its customers how and where to recycle. Different varieties of collection boxes, which were distributed throughout cities, were illustrated in the August 1940 issue of Shiseido Chainstore Alma Mater. 32

Shiseido Chainstore Alma Mater

vol. 2, no. 8, back cover,

August 1940

[sh02_CS_1940_08_2]

|

| |

Again, the reactionary and restrictive ideological context of this recycling effort did not entirely restrict its creative mode of expression, as evidenced in the playful editorial layouts using cut photographs of piles of recycled containers for the contours or actual shapes of bottles with the copy “One container can be the power of Asia.”

|

|

| |

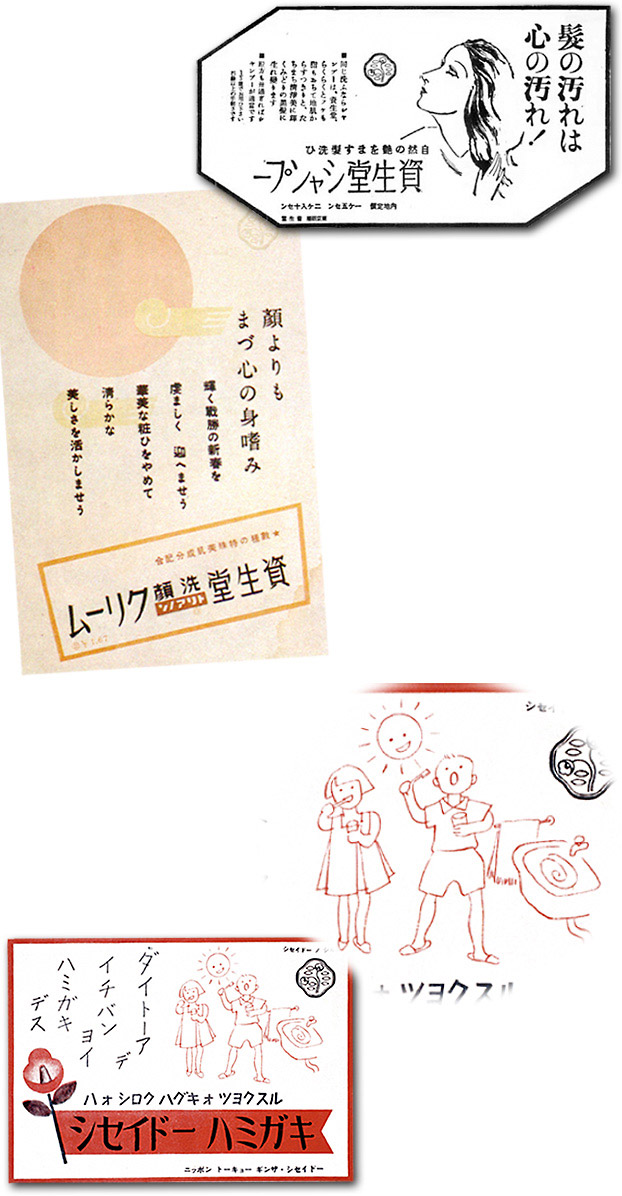

Another strategy the company used to negotiate the anti-luxury ordinances was to tie its products to the morality messages of the wartime spiritual mobilization movement. A newspaper advertisement from 1941 for Shiseido shampoo told women that “dirty hair makes a dirty spirit/mind!” (kami no yogore wa kokoro no yogore!). The illustration shows a clearly Western-looking woman gazing upward as if for spiritual guidance as she strokes her long hair. It does not emphasize the beautifying aspect of the product, which might be linked to vanity and luxury, but rather promotes cleanliness (as next to godliness).

|

|

|

Other Shiseido products were similarly promoted; toothpaste was endorsed for keeping teeth and gums healthy (rather than for making them beautifully white). In a toothpaste ad from 1943, children brushing their teeth exclaim, “We are the best teeth brushers in Greater East Asia,” with the text written in uneven katakana lettering to imitate a child’s handwriting that makes it appear as if the two figures are speaking the copy.

Another 1943 ad for Shiseido face washing cream with the national emblem of the rising sun was clear to emphasize priorities while still accentuating the importance of cosmetic hygiene practices. It read, “Before thinking about your face, first be mindful of the appearance of your spirit/mind (kao yorimo mazu kokoro no midashinami). 33

Ad for Shiseido Face Washing Cream, 1943

[sh06_1943_FaceWashingCream]

|

| |

A 1942 ad celebrating the fall of Singapore with a floral framed score for the “Singapore Victory Song” (to be sung throughout the nation until the Americans and British were defeated) was accompanied by the catchphrase “healthy teeth proud nation” (kenba hōkoku). Genmai (brown rice) for meals was put forward as a good method for polishing teeth in addition to using Shiseido toothpaste (1943). Moreover, the high quality of Shiseido toothpaste, a 1942 ad touted, ensured that you only needed a little to be effective, so it was, in fact, the more economical (keizaiteki) choice.

Another way Shiseido endorsed its cosmetics was their practical effectiveness against medical ailments; for example, vanishing cream was good at soothing chapped skin (are dome) as well as providing valuable protection under light cosmetics. The company continued to diversify into a range of products, including: Hifumoto cream to heal skin wounds and burns (1942); Asia-brand shoe polish for men’s shoes; and ball-point pens, which were marketed as “culture weapons” (bunka no heiki).

|

|

The ad at right encourages consumers to recycle their empty cosmetic jars (“Please do not

throw away your empty jars”–Shiseido is offering

5 sen back to people who

return the jar).

Ad from Asahi Shinbun

newspaper, February 1944

[sh06_1943_Asahi_NewspaperAd]

Visually the advertisements display a marked graphic simplification in terms of composition and color from the early 1940s, both responding to government publishing regulations and due to a desire not to look ostentatious during a time of national sacrifice.

This image below shows a range of ads for different products, with Shiseido on the far left (enlarged in the left detail). The wartime slogan “Fight to the Bitter End” (Uchite Yamamu) appears. The government restricted the amount of advertising space companies could have, so newspaper advertisements were only two or three lines each.

Ads from Asahi Shinbun newspaper, March 1943

[sh06_1943_Asahi_NewspaperAd] |

| |

Yet even within the stripped down wartime palette, it is evident that designers developed creative approaches to their editorial layouts maximizing the three colors of black, white, and red in eye-catching simple compositions.

|

|

| |

A note from Shiseido Co., Ltd.

Given the value, age, and cultural background of these materials, we have not altered original phrases

or images that may seem inappropriate in light of our awareness of human rights today.

掲載図版における今日の人権意識に照らして

適当でないと思われる語句や表現についても、

作品の時代的背景と文化的価値とをかんがみ、

原版のまま掲載しています。

On viewing images of a potentially disturbing nature: click here.

|

|

|