| |

COSMOPOLITAN GLAMOUR

Rich Rewards: Images of Transnational Beauty

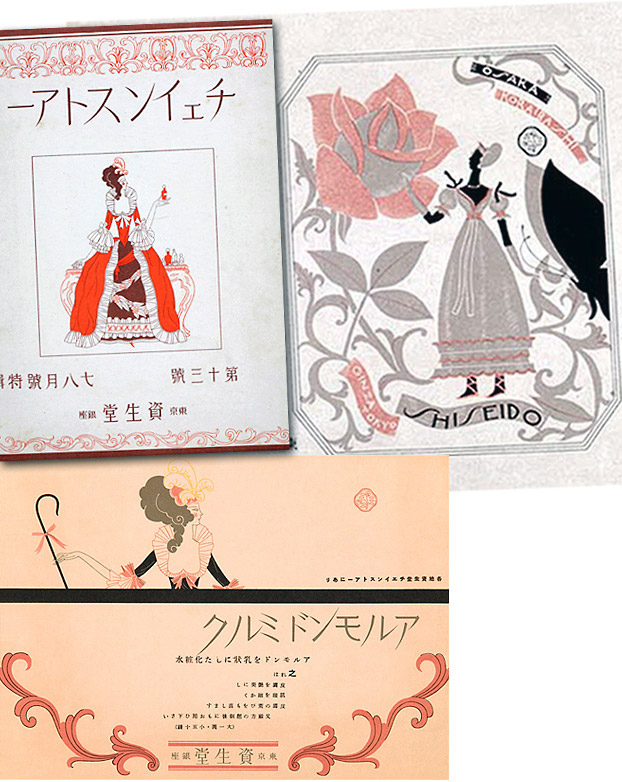

Early on, Fukuhara Shinzo seized on the term “rich” in Shiseido’s advertising copy to connote the luxury, elegance, glamour, and stylishness he hoped to associate with the company’s products. This image of richness was visually amplified in advertisements through colorful illustrations of exotic women of leisure in gorgeous dream interiors. These cosmetics advertisements sold a total cosmopolitan lifestyle of elegance. Although this lifestyle was largely unattainable for most Japanese consumers, it represents a constructed aspiration that clearly appealed to the large number of consumers buying Shiseido products who were willing to pay a premium for the company’s purportedly higher quality goods and this self-styled image.

Richness was synonymous with “deluxe,” which even became a separate Shiseido skincare line launched in 1936 that had “De Luxe” penned in romanized script calligraphy framed by delicate arabesques on the advertisements and packaging (see De Luxe skincare bottle images in the Introduction). The word deluxe was also written in Japanese on advertisements as saikōhō, the acme or peak, with the attending katakana gloss of “dorrukusu.”

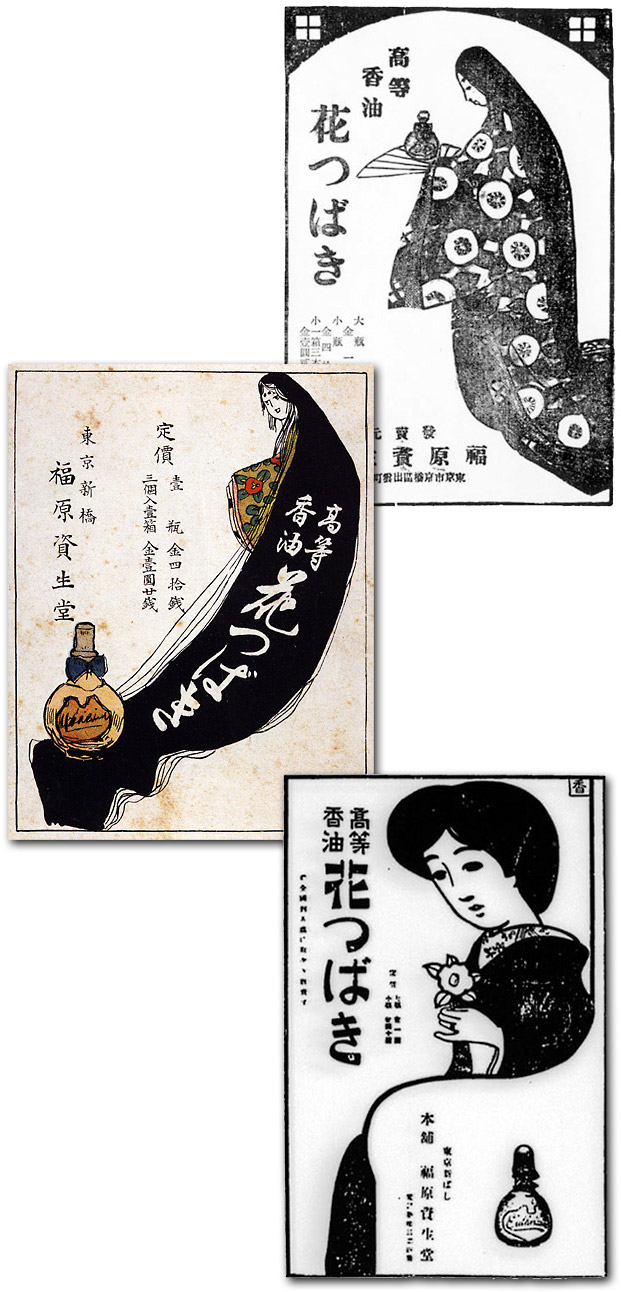

Shiseido’s advertising is populated by a dazzling array of elegant women from around the world and from across the ages, spanning from classical antiquity until the present. Early Taishō-period print advertisements from around 1914 for Shiseido’s scented hair oil Hanatsubaki (Camellia) feature historical images of local beauties from Japan’s imperial heyday, the Heian period (794 to 1185), associated with literary classics such as The Tale of Genji and The Tale of Ise, which would have been immediately familiar to the entire populace.

|

|

With their dramatic porcelain-white powdered skin and layered opulent robes, these imperial court beauties proudly display their unbound long flowing black hair (taregami) that is the central visual feature of these images and becomes an exaggerated compositional device for foregrounding the product and its application.

Hanatsubaki hair oil (right)

newspaper ad, 191

[sh01_1915_a019_MagazineAd]

Magazine ad, 1916 (above)

Shin Engei

[sh01_1914_a017_MagazineAd]

Just a few years later in 1916, however, the feminine ideal featured in the advertisements was markedly updated to the contemporary, showing a Japanese woman with a more decidedly 20th-century upswept coiffure (sokuhatsu) and trendy kimono.

Hanatsubaki hair oil ad (right)

Shin Engei magazine, 1916

[sh01_1916_a021_MagazineAd]

Harkening back to these classical images would not only have tapped into sentiments about authentic Japanese beauty and taste (neither Chinese nor Western in origin), but would also evoke positive associations with Japan’s majestic imperial legacy, already a common trope in Meiji-period politics and public culture.

|

| |

The woman’s modish style is mirrored in the distinctive stylized blocky typography used for the product name, clearly inspired by art nouveau graphics, and the advertisement’s bold editorial layout indicates the form of a modern armchair with the sweep of a single curved line that also provides a delicate visual frame for the product featured below.

|

|

|

Examples of art nouveau fonts that display a similar modulation of line to the Hanatsubaki logo in the Shiseido advertisement above. |

|

| |

Illustrated instructions on how to do such contemporary “all back” hairstyles that tied into advertising imagery were featured regularly in Shiseido’s free, consumer directed public relations publication Shiseido Monthly (Shiseido Geppō ) from its inception in 1924 along with articles on current fashions for the body and the home reinforced the company’s constructed image of a particular beauty ideal.

|

|

| |

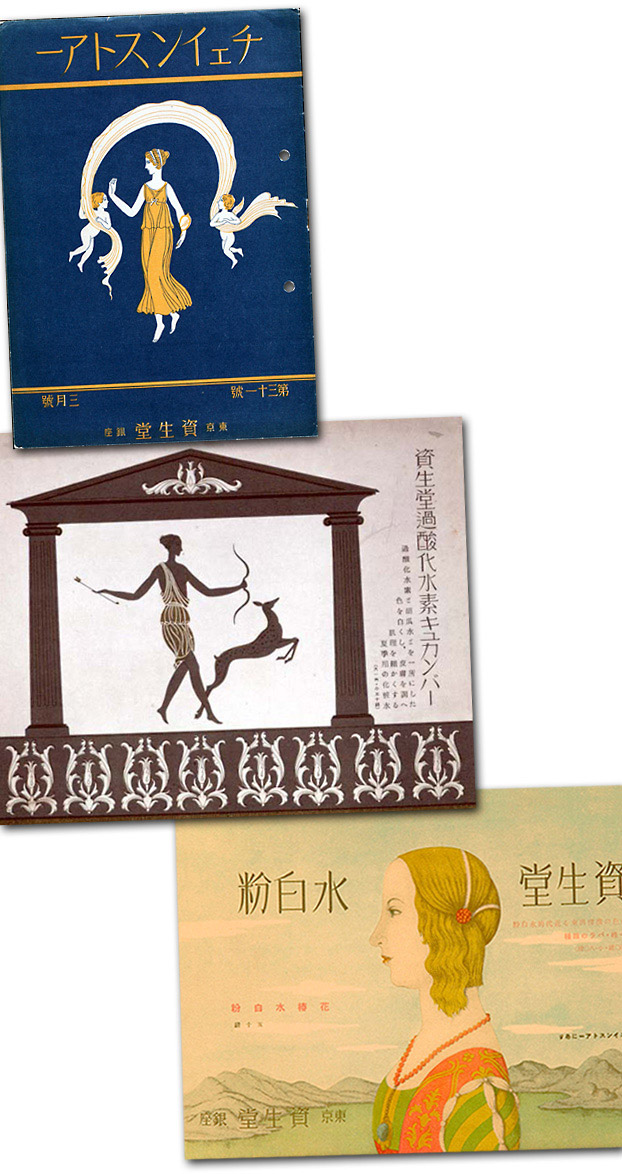

The diversification of ideals of beauty moved both diachronically and internationally, showing female figures with Western-style curly hairstyles and flapper-era dresses.

|

|

On the cover of Shiseido’s in-house public relations journal Chainstore, a Roman beauty holding a mirror is heralded by two flying cherubs draping a fluttering scarf around her.

Chainstore 31, March 1930 (left)

[sh02_CS_1930_03_1]

Or in another poster (below) for Peroxide Cream with cucumber, Diana, the legendary Roman goddess of the hunt, who is associated with nature, chastity, athletic grace, and beauty, is accompanied by a leaping deer and stands poised with bow and arrow under a classical edifice.

Even Renaissance

beauties rendered in

the famous painting

styles of the Italian

masters were

invoked to sell liquid

face powder.

Shiseido liquid powder

poster, 1926

[sh01_1926_e026_poster]

|

| |

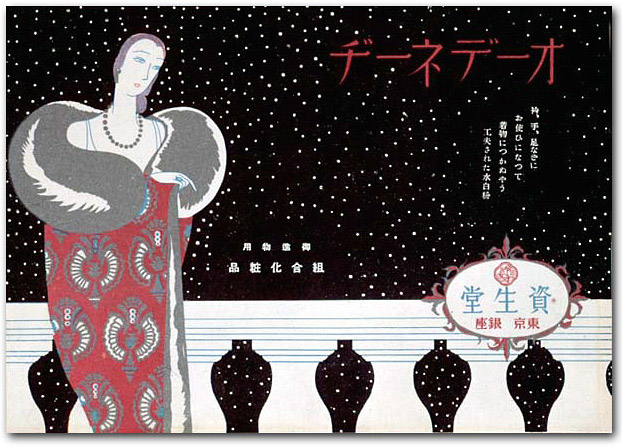

Female figures from other historical periods and geographical places abound, ranging from the grandiose, corseted hoopskirt ball gowns of the age of Marie Antoinette to the modern flapper with her short bobbed hairstyle and luxurious furs.

|

|

|

|

|

| |

While it is unclear whether the images were keyed to particular products, as the product line was diverse and ever-expanding during this time period, there is certainly a clear association between representations of Japanese women and hair products, speaking specifically to the coiffure and hair treatment issues of women locally. But when it comes to products of a clearly Western origin, such as face creams that were evoking images of an exotic cosmopolitan lifestyle abroad, the use of Western women from a variety of periods and places was common. Either way, the message was consistent; Shiseido cosmetic products promote beauty and elegance that are both timeless and freshly contemporary. They contribute to a worldwide, universal aesthetic of beauty that is cosmopolitan and transnational.

|

|

|

Unhindered by the restrictions of history, Shiseido could bring Marie Antoinette and the chic, kimono-clad modern Japanese “New Woman” (atarashii onna) into conversation; as they both gaze into a small hand-held mirror, clearly engaging in a conversation about beauty. 11

Shiseido Cosmetics, poster, 1930

[sh01_1930_e035_poster] |

|

| |

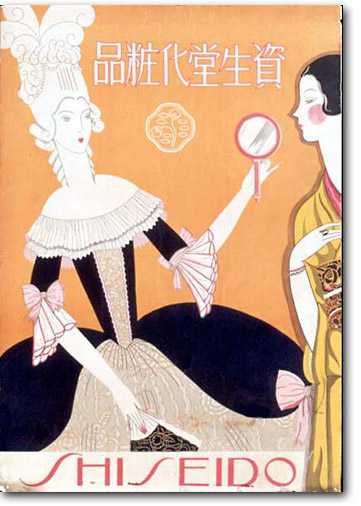

Mirroring the Gaze

The gaze is a visual centerpiece of Shiseido advertising, which exhibits women gazing at themselves in the mirror for self-inspection, or showcases mirrors reflecting their images to an external audience—implying the general gaze of society, but also more specifically the inquisitive gaze of women and the sexualized gaze of men.

|

|

| |

While a woman may ostensibly use cosmetics for her health and

well-being, fundamentally she is encouraged to use it to look better,

and hence be more appealing to the opposite sex as well as to her

female competition. A successfully beautiful woman, then, as

evidenced in one 1927 Shiseido Cold Cream poster (below), can enjoy a

fantasy life of leisure based on the widely circulated images of the

French colonial imaginary that includes attentive servants

(presumably colonial subjects from North Africa) who offer an array

of beauty products in the evening after the woman has returned from a

night of elegant socializing.

|

|

| |

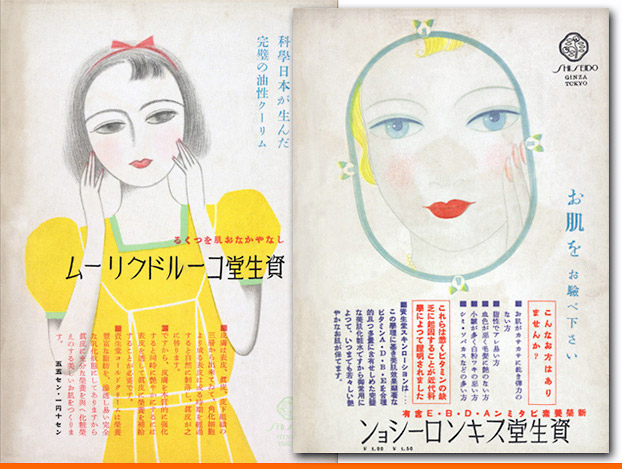

The female consumer subject must monitor her own beauty through attentive inspection, and by using “scientific Japanese” products like Shiseido’s “perfect oil-based cream,” she can strengthen and nourish the three layers of her skin “from the core to enliven the outer visible layer.”

|

|

|

| |

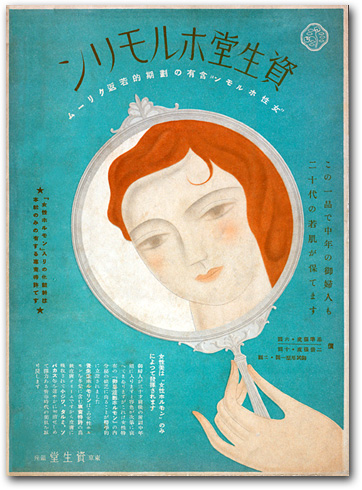

Along with advertisements targeted at younger women, some clearly address “middle-aged women” (chūnen no gofujin) who are told that they can look like they are in their 20s again. Despite the traditional veneration of age and wisdom in Japan, clearly the cult of youth already prevalent in Euro-American advertising was well implanted by the 1920s. In an advertisement for Shiseido Hormoline cream, the world’s first skin cream enriched with female ovarian hormones, launched in 1934 and targeted at middle-aged women seeking to turn back the clock, just the mirror and its reflected visage are shown, implying the substitution of the subject with the consumer herself as she presumably gazes at her own potentially younger looking reflection. for Shiseido Hormoline cream, the world’s first skin cream enriched with female ovarian hormones, launched in 1934 and targeted at middle-aged women seeking to turn back the clock, just the mirror and its reflected visage are shown, implying the substitution of the subject with the consumer herself as she presumably gazes at her own potentially younger looking reflection.

Shiseido magazine ad, 1936

[sh01_1936_d006_no1167_MagAd] |

|

| |

In this process, she is also deracinated from an Asian woman to a Western woman, something that was common throughout Japanese consumer advertising of the period. This was not a denial of Japanese-ness or Asian-ness, but rather a wishful affirmation of the mutability of consumer identity and the ability of commodities to enable self-fashioning that was not subject to national, racial, cultural, or even historical limitations.

|

|

The Modern Japanese Woman as Consumer-Subject

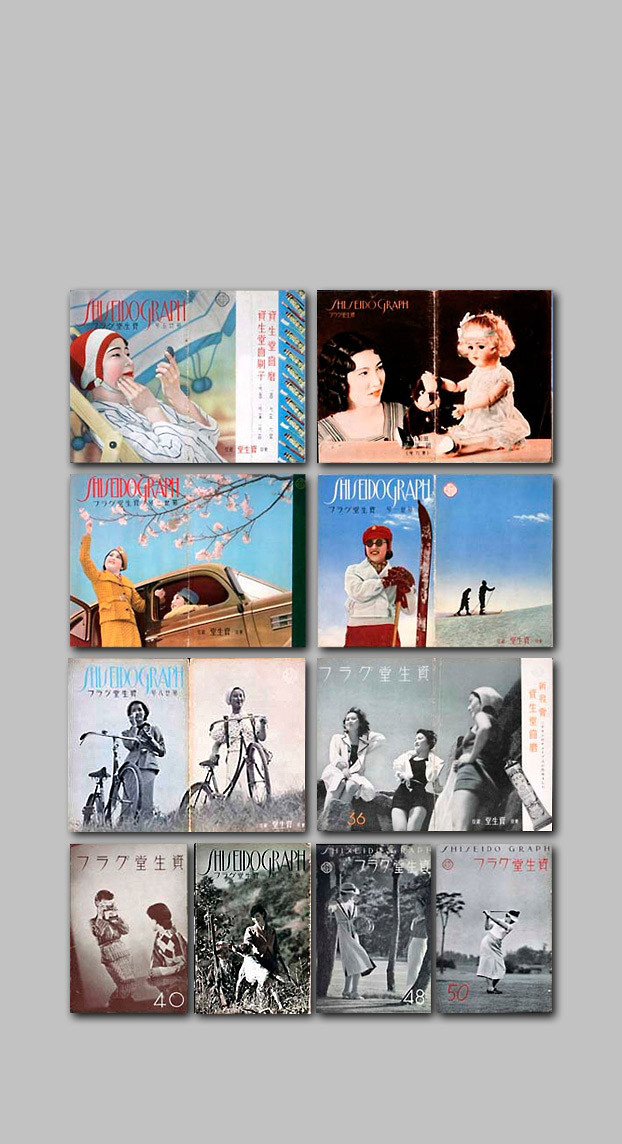

Shiseido’s promotional aesthetics were part of an emerging, worldwide culture of beauty that was elegant, freshly contemporary, cosmopolitan, and transnational. Despite the emphasis on images of leisure, Shiseido advertising sought to appeal to a broad range of women consumer-subjects, from working women to bourgeois housewives. Here, selected covers from Shiseido Graph magazine—published from 1933 to 1937—feature a vivid array of independent women in chic, contemporary scenes.

Selected covers from Shiseido Graph magazine, 6/1933–9/1937

(top six are front & back cover spreads; lower four are front covers) |

|