| |

Canton Happenings

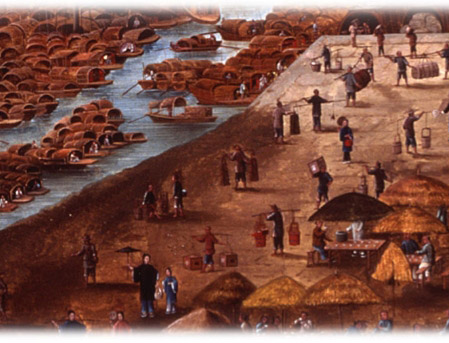

The foreign community in Canton was comprised largely of young men out to make their fortunes, who left their families for years at a time. The number of ships arriving per year grew from about 20 in the 1760s to 300 in the 1840s. As each large ship held from 100 to 150 men, the total number of foreign traders increased from a few thousand to tens of thousands in 100 years, but they lived in a city of millions of Chinese. On the waterfront, the small number of Western men mingled with large groups of Chinese porters, shopkeepers, craftsmen, and families on sampans. Many of these Chinese workers made their living from supplying provisions to the Western sailors and traders.

|

|

|

| |

Since the Chinese used few dairy products, Western merchants kept their own animals in the yard beneath the hong walls to provide meat and milk for their diet. “Chopboats” with a capacity of 600 chests carried tea and other trade goods to waiting ships, sold daily supplies to the merchants, and served as homes to many Chinese workers and their families.

|

|

|

Above and left, details from “A View of Canton from the Foreign Factories,” ca. 1825

unknown artist, China Guangzhou (Canton)

Hong Kong Museum of Art

[cwC_1825_AH928]

|

| |

The Cantonese lived not only on land but also on the water—on small boats that provided supplies for the foreign and Chinese merchants, and on larger houseboats anchored in safe harbors. Aside from infrequent contact with a Chinese official, and daily business with Chinese merchants, the Chinese whom Westerners saw most often were these sampan people. Each trading company commissioned licensed Chinese merchants, called compradors, to take charge of provisioning the factories and the ships. The comprador collected wages for all of his employees, and often organized the entire voyage from Macau to Canton and back, taking care of official permits (“chops”), pilots, and supplies. His men would also live in and guard the factories when the traders had left. The ship compradors lived on their sampans, organizing the delivery of enormous amounts of supplies, which they bought on the Cantonese markets. During the trading season a single ship could consume thousands of pounds of fruit, vegetables, pork, mutton, fish, and a whole cow every two or three days.

The sampan sellers provided all sorts of other services, too. Barbers served both the Chinese and Westerners. Many boats provided coal, charcoal, and firewood for fuel, while others specialized in ships’ supplies. Many others raised ducks on nearby farms and supplied eggs and duck meat to the ships. The “flower boats,” or floating brothels, were also a conspicuous sight in the harbor. The women on the boats lived in near slavery to their procurers, who could be hong merchants or compradors who paid off the officials to allow the trade. Even though it was illegal for women to enter the factories, compradors could smuggle them in secretly.

|

|

|

| |

The flag on the colorful boat in front says “Heavenly Women,” indicating that it is a “flower boat” or floating brothel. The prominent Anglican church and the American steamship Spark, owned by Russell and Co., are lined up behind it. Chinese officials banned Western women from the factory quarters, but several did arrange secret visits. Meanwhile, the foreign and Chinese men found many women to serve their needs in the harbor.

“Loading Tea at Canton,” ca. 1852

by Tinqua

Peabody Essex Museum [cwC_1852c_E83553]

|

|

| |

The foreigners also hired “linguists” to communicate with the Chinese merchants and officials. Since the Qing court prohibited foreigners from studying Chinese in Canton, nearly all the traders had to rely on these Chinese interpreters. They had to speak Cantonese and Mandarin and write classical Chinese in order to work with the officials and local population, and originally the main foreign language they used was Portuguese. After the 1730s, pidgin English developed as the most common means of communication. This language mixed together Portuguese, English, Malay, and other vocabulary with a syntax close to Chinese to create a business language of intercultural communication. Although the language may sound strange to our modern ears, the speakers of pidgin were highly intelligent, flexible Chinese men who knew how to get their point across well. This excerpt from a conversation between the American trader Hunter and the hong merchant Houqua shows how they shared news with each other:

Hunter : “Well, Houqua, hav got new today?”

Howqua: “Hav got too muchee bad news. Hwang Ho hav spilum too muchee.”

Hunter: Man-ta-le [Mandarin, official] have come see you?”

Howqua: He no come see my, he sendee come one piece ‘chop’. He come tomollo. He wanchee my two-lac dollar [200,000 dollars].

Hunter: You pay he how muchee?

Howqua: My pay he fitty, sikky thousand so.

Hunter: But s’pose he no contentee?

Howqua: S’pose he, number one, no contentee, my pay he one lac.”

In other words, because of flooding on the Yellow River, the hoppo asked the hong merchants to “contribute” 200,000 each for relief funds. Howqua gave a counter offer of 50 to 60,000, but he was prepared to pay 100,000 if necessary. Howqua not only knew how to bargain with Chinese officials, but he trusted his American counterpart well enough to let him in on the details. Both the hong merchants and the foreign traders shared interests in keeping their profits out of the hands of officials to the extent possible. Although neither side could speak the other’s native language, pidgin allowed them to communicate a great deal beyond basic business deals.

Crises and Trials

Inevitably, some of the foreign visitors embroiled themselves in conflicts with the local population. Paintings based on eyewitness accounts depicted these critical public events.

|

|

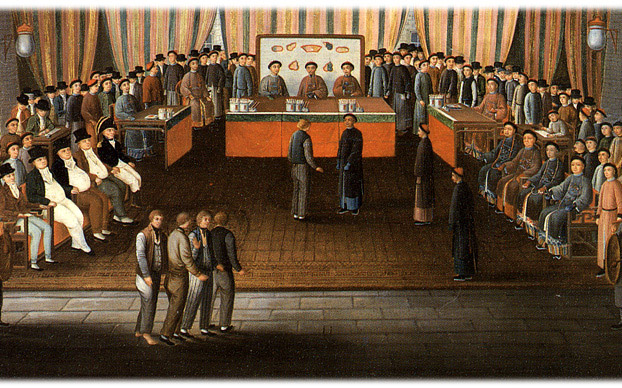

Court of Inquiry

Into the Trial of Sailors of the Ship Neptune

|

|

| |

This pair of paintings shows the court of justice held at the British factory in Canton to investigate a riot caused by sailors from the East Indiaman Neptune in 1807. On the left, the sailors, magistrates, merchants, and official escorts arrive in the public square outside the factory. On the right, inside the court, prominent Chinese and Western merchants and the sailors sit in front of Chinese judges. Before the Opium War, foreigners reluctantly accepted the Chinese right to sentence their rowdy sailors in order to continue trading. After the Opium War, they insisted on judging their own nationals in their own courts.

Trial of Four British Seamen at Canton, 1 October 1807

attributed to Spoilum

“Scene Outside the Court”

Hong Kong Museum of Art [cwC_1807_AH6428_sc]

“Scene Inside the Court”

Hong Kong Museum of Art [cwC_1807_ct108]

| |

| |

In the Neptune incident of 1807, Chinese authorities clashed with foreign merchants over the settlement of a violent fight. It led to the first Chinese trial at which foreigners were present. On February 24, 1807, drunken sailors on shore leave from the East India ship Neptune, angry at a robbery of their fellow seamen the day before, had caused a riot, killing a Chinese man and wounding several others. In response, the Qing officials stopped all trade and convened the court to investigate the incident. Mowqua, one of the leading hong merchants, took responsibility for negotiating a settlement. He was in a difficult position, caught between the demands of Chinese authorities for punishment of the guilty parties and the insistence of the foreign merchants that the court prove specifically who had killed the Chinese man. The English ship captains could not get their sailors to confess guilt, but Chinese officials threatened Mowqua with heavy fines and torture if he could not deliver up the killer. The officials agreed to hold trials in the English factory to determine a sentence, and the judges examined 52 sailors who were on shore during the incident. All the sailors denied that they had killed a Chinese man. After three trials, the Chinese judge found one sailor guilty of accidental homicide and ordered him to be detained in the English factory. He acquitted the other 51 men. Next year the sailor was released on payment of twelve taels, or four English pounds, the Chinese penalty for accidental killing.

|

|

|

| |

Outdoor Scene (detail): the scene outside the Chinese Court of Justice at Canton shows the arrival of four convicted British seamen (upper right corner) from the East Indiaman Neptune in 1807. Crowds of Chinese and foreigners have assembled in the square in front of the hongs between Old China Street and Hog Lane. Some are staging a procession with flags and gongs to welcome the officials. Others are setting down a sedan chair and resting next to tents, while British policemen watch them. Chinese wearing red caps have official status.

“Trial of Four British Seamen at Canton, 1 October 1807,

Scene Outside the Court”

attributed to Spoilum

Hong Kong Museum of Art [cwC_1807_AH6428_sc]

|

|

|

| |

Indoor scene (detail) of the Chinese Court of Justice held at the British factory of Canton, 8 March 1807. Four British merchants sit on the left facing their Chinese counterparts on the right. A Chinese judge interrogates one of the defendants while four other sailors await their turn. Two linguist interpreters stand next to the judge. In this early incident, both sides settled for relatively lenient sentences. Only one sailor was convicted, and he was let off after one year for a small fine. Later incidents led to more heated conflicts between Western and Chinese conceptions of justice.

“Trial of Four British Seamen at Canton, 1 October 1807,

Scene Inside the Court”

attributed to Spoilum ca. 1852

Hong Kong Museum of Art [cwC_1807_ct108]

|

|

| |

In this celebrated trial, both Western and Chinese merchants had to submit to the Qing officials who ran the court. Hong merchants like Mowqua exerted considerable influence on local government, but he had to pay heavy fees to officials and take responsibility for the unruly barbarians. Although Mowqua nearly lost all his money in settling the Neptune affair, he succeeded in restoring trade and finding a guilty man. Even though China and England had different justice systems, the two groups had to accept the formal authority of the Qing court. The lenient punishments handed out followed the standards of Chinese law. Tensions increased in the 19th century because of the Qing government efforts to stamp out the opium trade. Later, after the Opium Wars of the 1840s and 1850s, the Westerners imposed their own laws on China in the treaty ports. In 1807, however, the Chinese and Westerners still stood on an equal level.

|

|

The Great Fire of 1822

The Burning and Aftermath of the Canton Factories

|

|

| |

Fires frequently struck the foreign hongs and the city in general. When disaster struck, as in 1773, 1777, and 1778, the foreigners and Chinese worked together to respond quickly; both used their water-pumping fire engines. The linguists assembled to direct fire-fighting operations and help coordination between Chinese and foreigners. But the tightly packed wooden houses and shops of the Chinese city could easily go up in flames. On November 1, 1822, in a cake shop outside the city wall, north of the factories, a baker set off a fire accidentally while he was melting sugar. In the narrow streets, fanned by strong winds, the fire spread rapidly through the city, destroying thousands of shops. The foreign merchants could not obtain enough water for their fire engines, and the Chinese viceroy did not allow them to destroy local houses to create a firebreak, but Chinese and foreigners together formed bucket brigades. They saved some of their woolen goods, but the vulnerable shops on Hog Lane quickly ignited, destroying nearly all of the factories. The flames were so fierce that the merchants and their staffs had to flee from the land onto their boats into the river.

The greatest losers in the fire, however, were the Chinese shopkeepers and hong merchants, most of whose warehouses were destroyed. Howqua, by sending very respectful requests to the viceroy, obtained the remission of the taxes of 140,243 taels owed by the foreigners, and deferral of 260,000 taels owed by the hong merchants. The Chinese officials demonstrated generosity toward the foreigners, even though Sino-foreign relations were becoming increasingly tense because of conflicts over rising opium imports and incidents of conflict between sailors and local Chinese. Only the walls remained, but the foreigners began rebuilding immediately. The fire illustrates how closely tied the lives of the foreigners and the Chinese were to each other. They shared in the profits of trade, but also in the dangers of a large city.

Three paintings that depict the start, burning, and aftermath of a fire that demolished the foreign factories in Canton in 1822.

top: Hong Kong Museum of Art [cwC_AH64031]

middle: Peabody Essex Museum [cwC_M22764]

bottom: Peabody Essex Museum [cwC_E79474]

|

|

| |

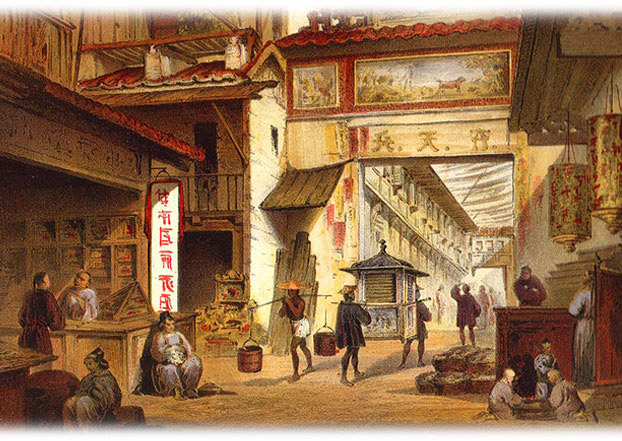

The Western factories basically contained only warehouses, meeting rooms, and small bedrooms for their exclusively male population. They were but outposts for a few businessmen on the vast Asian continent. From the Chinese point of view, Westerners were only a small part of a huge commercial network spanning interior China and the maritime world. In the back streets of Canton, in the Chinese city, an urban population lived its life independently of the foreigners.

|

|

|

| |

William Heine, a young German artist who accompanied Commodore Perry’s famous expedition to Japan that made stops in China in 1853 and 1854, made sketches and engravings of the parts of Chinese life that he could see, like Old China Street, one of the two narrow alleys that ran between the foreign factories. He depicted the bustling market activity of the Chinese street, including the exotic hats, queues, carrying poles, and gowns of the Chinese population. The sedan-chair bearers and the coolie carrying water or manure buckets were typical sights of a Chinese street; however, the Chinese characters are not accurate and the picture at the top of the gate with a dog is a Western scene, not a Chinese landscape.

“Old China Street in Canton,” 1856

by William Heine

[cwC_1856_Heine_OCSt_bx]

|

|

|

| |

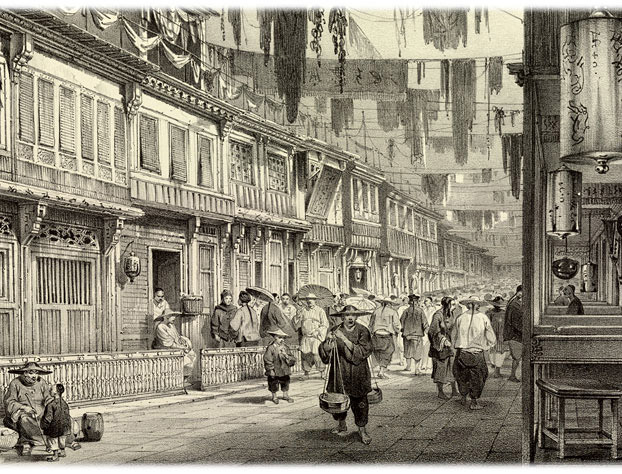

New China Street: the drawing emphasizes the narrowness of the street filled with large crowds of people. The typical Chinese shops have showrooms on the ground floor and family quarters in the overhanging second story, covered with lattice shades.

“New China Street in Canton,” 1836–1837

by Lauvergne; lithograph by Bichebois

National Library of Australia [cwC_1836-37_AN10395029]

|

|

|