| |

Merchants West & East

Not just anyone could enter the China trade, on either the Western or the Chinese side. Only a small number of wealthy and powerful men could enjoy its large risks and profits. The members of the English East India Company and the Dutch VOC were some of the largest and most powerful landowners in the country, who had great influence in the politics of their country. Since the elites depended on trade for much of their income, they could use their political influence to direct policy toward protecting their business profits, even at the cost of war.

|

|

Merchants of the Canton Trade

|

|

|

“A Merchant Naval Captain,” 1830–1835

“A Merchant Naval Captain,” 1830–1835

attributed to George Chinnery

The unidentified captain wears a naval jacket and stands with his telescope on the deck of a ship, off the shore of China, probably Canton. The China trade captains and supercargoes were usually young men from prominent families who left home to make their fortunes. The captain commanded the ship, and the supercargo took charge of the sale of commercial goods. Sometimes these roles were one and the same.

National Maritime Museum

[cwPT_1830c_nmmBHC3169]

|

“The Hong Merchant Mouqua,” ca. 1840s

by Lam Qua

“The Hong Merchant Mouqua,” ca. 1840s

by Lam Qua

Mouqua (or Mowqua, Chinese name Lu Guangheng), was one of the most prosperous hong merchants. He wears robes indicating his official rank. The suffix -qua (guan in Mandarin) means “official.” The hong merchants did not get official degrees through the regular examination system, but obtained their posts by purchasing them at high prices from the regular officials. They were responsible for all foreign trade in Canton.

Peabody Essex Museum

[cwPT_1840s_ct79]

|

| |

During the Seven Years War, from 1757 to 1763, England and France fought for global domination primarily to protect their trading interests. At the same time, the East India Company, greedy for revenue to support its military needs, took over the prosperous parts of Bengal producing cotton and rice. Then it turned its attention even more strongly toward China. The inexhaustible demand for tea in England and the abundant supplies of the finest teas in China promised great profits. With Bengal as a base, the merchants aimed to ship Indian commodities to China in exchange for tea and to use the profits in England to support the Company’s growing intervention in India. At the same time, private traders on the Company’s ships promoted opium sales for their own personal gain.

Opium was illegal in England, and many missionaries condemned the opium trade. Officially, the East India Company did not trade in opium, but private trade enriched many of its members. After the abolition of the Company’s monopoly in 1834, opium traffic increased rapidly.

The Americans tried to enter the China trade even under British colonial rule, but the British, calling them pirates, tried to exclude them from the monopoly. Some Americans could ship goods from Batavia to China using Dutch ships, and others used American ships from the African slave trade to take goods to China. After independence, with the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1783, the Americans quickly entered the China trade. The first legal American ship to arrive in China was the Empress of China, which arrived in 1784 with a cargo of silver and 30 tons of ginseng. It returned with a large cargo of tea and silk.

|

|

|

| |

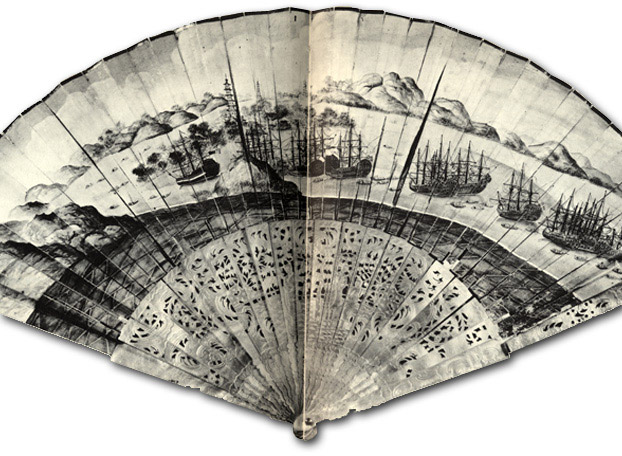

This fan features the only known picture of the first legal American ship to trade in China, the Empress of China (on the far left at Whampoa anchorage). She arrived in 1784 with a cargo of silver and 30 tons of ginseng and returned with a large cargo of tea and silk. Before 1784 the British protected their trade monopoly by excluding Americans, as colonial subjects, from the lucrative China trade. Some Americans did get into Canton illegally, but only after the negotiation of the Treaty of Paris in 1783 ending the Revolutionary War could they trade with China openly.

Fan depicting Whampoa anchorage, China, ca. 1784

Historical Society of Pennsylvania [cwBTW_1784c_EmprsCh_met80]

|

|

| |

Unlike the British, the Americans entered China as individuals, without the backing of a chartered company. They regarded the East India Company as a corrupt defender of empire. As individuals, or representatives of merchant syndicates, they could act more flexibly in response to Chinese official restrictions, either by negotiating their way out of trouble or by actively participating in the smuggling trade. Until the end of the 18th century, very few Americans stayed for long in Canton. Samuel Snow, from Rhode Island, built the American factory in 1798, but until the 1820s there were never more than 12 Americans in residence in China. Samuel Russell, an orphan from Connecticut, began as an apprentice clerk, learned the skills of the trade, and founded the first permanent American firm, Russell & Co. in 1824. It became the largest American firm, dealing in tea, silk, and opium before and after the Opium War, and lasted until 1891.

|

|

|

Samuel Wadsworth Russell, born in Middletown, Connecticut, founded Russiell & Co., the first American firm in Canton, in 1824. His firm prospered from trade in silk, tea, and opium through the 19th century. Russell returned to the U.S. and built a mansion in Middletown, filling it with gifts from the hong merchant Howqua and many other Chinese artworks. Samuel Wadsworth Russell, born in Middletown, Connecticut, founded Russiell & Co., the first American firm in Canton, in 1824. His firm prospered from trade in silk, tea, and opium through the 19th century. Russell returned to the U.S. and built a mansion in Middletown, filling it with gifts from the hong merchant Howqua and many other Chinese artworks. |

|

| |

The Chinese hong, or guild, merchants also belonged to a select group. Since the 16th century, the Chinese court had given monopoly privileges to certain merchants to trade with the Westerners. By the end of the Ming dynasty there were 13 official hong merchants. The Qing kept this quota, although the actual number fluctuated a great deal. To gain their monopoly privilege the merchants had to pay hundreds of thousands of taels of silver to the court, and they were responsible for any debts incurred by foreign traders. Their financial situation was always precarious. To keep out competition and ensure regular trade, they formed the Cohong guild in 1720, with a code of articles to regulate prices and customs, bridge the government officials and foreign traders, and collect customs duties and fees for the government. The richest merchants were Puankhequa (Pan Chencheng), Mowqua (Lu Guangheng) and Howqua (Wu Bingjian). Mowqua (1792–1843), pictured in the box above, was active for over 50 years and served as head merchant from 1807 to 1811.

Many of the hong merchants were not native Cantonese but rather immigrants from Fujian. Like their English and American counterparts, they had left their homes to make a fortune in commerce. Puankhequa came from a poor village on the coast of Fujian and left home at a young age to travel on junks in Southeast Asia, going as far as Manila. He learned some Spanish and English, and may even have temporarily converted to Catholicism. He settled in Canton in 1740 and established close links with the English and Swedes. He even traveled to Sweden to meet the director of the Swedish trading company. On his death in 1788 Europeans praised him highly as:

...the richest, most educated, cleverest of all the Chinese merchants…. It would be difficult to find among the other Chinese merchants a man who combined such wealth and intelligence, and who knew so well, by his superiority of knowledge, his unrivaled character, his experience of business how to dominate and persuade others.

His fortune may have reached 15 million taels (US$22 million) at his death.

Howqua (1769–1843) was even richer, and invested his fortune of US$26 million with John Forbes in Boston. By comparison, the contemporary European financier Nathan Rothschild held capital equivalent to US$5.3 million in 1828.

|

|

|

Howqua, a leading merchant in Canton, was one of the richest men in the world in the early 19th century. Howqua, a leading merchant in Canton, was one of the richest men in the world in the early 19th century.

Howqua, 1830

by George Chinnery

Metropolitan Museum of Art [cwPT_1830_howqua_chinnery]

|

|

| |

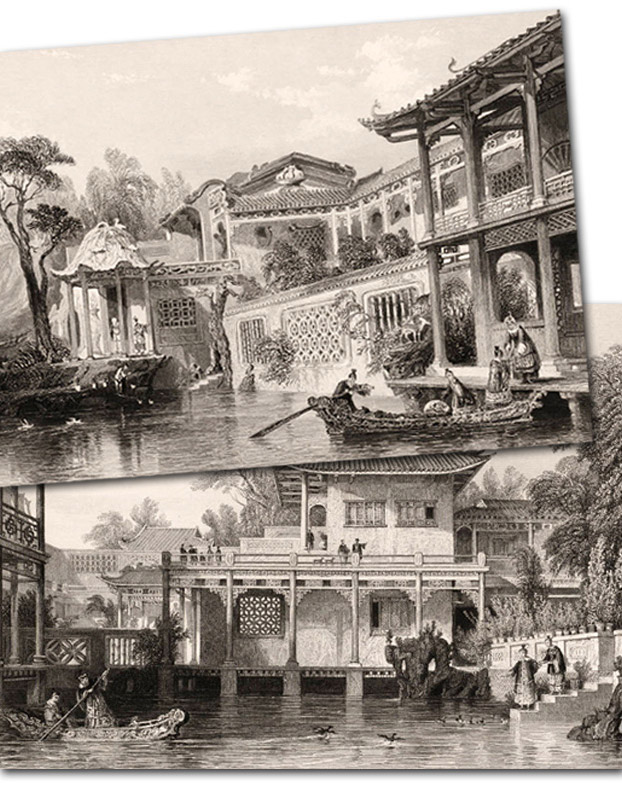

Despite the restrictions of the court, the Chinese and foreign merchants developed a great deal of respect for each other. Most foreigners regarded the hong merchants as honest and intelligent. Each hong merchant had to take responsibility for a particular foreigner, and the hong merchants faced constant scrutiny by officials to make sure the foreigners remained under control. They shared common appreciation for food and landscape gardens with their foreign guests, and the different cuisines and gardening practices influenced each other. In this way, personal contacts contributed to the larger vogue of “Chinoiserie” in the West. William Hunter, a young American who spent many years in Canton, described the merchants and their residences as follows:

As a body of merchants, we found them honourable and reliable in all their dealings, faithful to their contracts, and large-minded. Their private residences, of which we visited several, were on a vast scale, comprising curiously laid-out gardens, with grottoes and lakes, crossed by carved stone bridges, pathways neatly paved with small stones of various colours forming designs of birds, or fish, or flowers... William C. Hunter, The “Fan kwae” at Canton before treaty days, 1825-1844, by an old resident ... (Kegan Paul, Trench, 1882), p. 40

|

|

|

| |

“House of Consequa, a Chinese Merchant, in the Suburbs of Canton,” ca. 1842

by Thomas Allom

Beinecke Library at Yale University [cwC_Allom_1110097_yba] [cwC_Allom_1110104_yba]

|

|

| |

Sometimes the hong merchants held banquets for the foreigners at their country estates, which were elegant houses set in garden landscapes. William Hunter noted that such “very enjoyable” banquets included delicacies like bird’s-nest soup with sea cucumber, shark fins, roasted snails, and rice wine served in small silver or porcelain cups.

|

|

|

| |

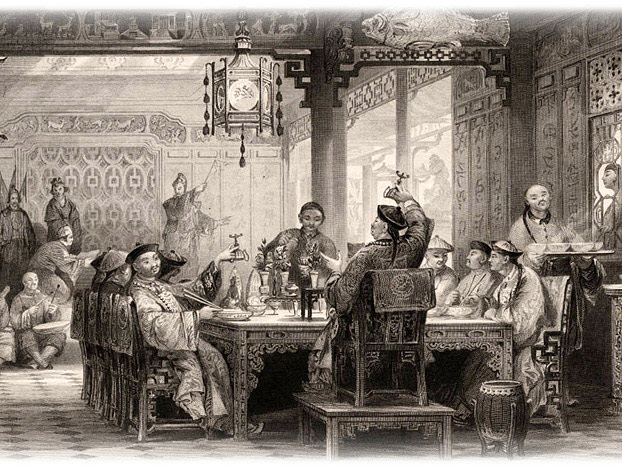

The hong merchants and the high-ranking officials, or mandarins, lived in opulent style. They entertained their guests, Chinese and foreign, at their houses with sumptuous banquets, including musical performances, theatre, and rare foods. In this picture, a troupe is performing a Chinese opera in the background while the senior official, in his raised chair, toasts his guests by emptying his wine glass and holding it upside down. The wooden fish at the top of the picture symbolizes wealth. Although the artist portrayed an imaginary scene here, many of his details are accurate.

“Dinner Party at a Mandarin's House,” ca. 1842

by Thomas Allom

Beinecke Library at Yale University [cwC_Allom_1110104_yba]

|

|

|