| |

Commodities and Luxury Exports

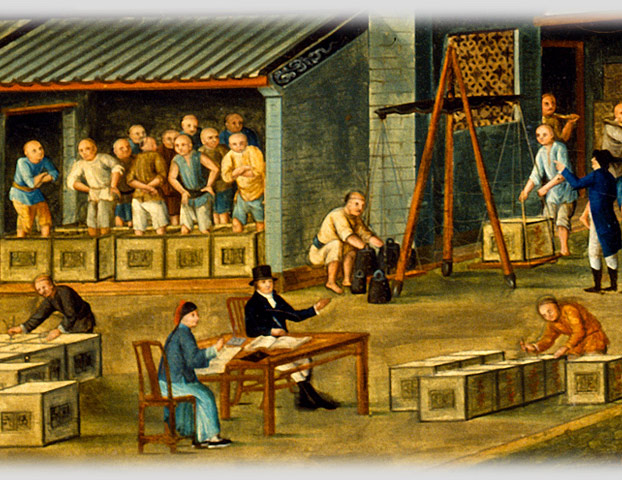

Luxury exports from Canton—fine porcelain, furniture, lacquer, paintings, and figurines—attracted the most attention as art objects but were not the primary goods of trade. The original China trade was a simple bulk exchange of commodities. Until the mid 18th century, 90 percent of the stock brought to Canton was in silver, and the primary export was tea. In 1782, for example, ships carried away 21,176 piculs (1408 tons) of tea, 1,205 piculs (80 tons) of raw silk, 20,000 pieces of “nankeens” (cotton goods), and a small amount of porcelain. After the mid 18th century, the British began shipping large quantities of woolens from their factories to replace the drain of silver bullion, but this was not enough to balance the trade. They also needed to supply goods to China from within the Asian trading networks. Raw cotton from India was the most important commodity, but they also brought in sandalwood, elephants’ teeth, beeswax, pepper, and tin.

|

|

|

When Americans entered the trade in the 1780s, the primary product they had to offer besides silver was furs. Neither woolens nor furs suited the subtropical climate of Canton very well, so it is not surprising that sales were slow. The Americans discovered that they could also profitably import ginseng, a popular medicinal root, and beche-de-mer, or sea cucumber, a delicacy served in soups at Chinese banquets. When Americans entered the trade in the 1780s, the primary product they had to offer besides silver was furs. Neither woolens nor furs suited the subtropical climate of Canton very well, so it is not surprising that sales were slow. The Americans discovered that they could also profitably import ginseng, a popular medicinal root, and beche-de-mer, or sea cucumber, a delicacy served in soups at Chinese banquets.

Ginseng, used in the manufacture of medicines, became one of the main commodities exported to China by Americans, especially as North American fur populations became decimated.

“Medicine Shop, Canton,” ca. 1830

Unknown Chinese artist

Peabody Essex Museum

[cwSHOP_E82547] |

|

| |

The World of Tea The World of Tea

Tea was the top Chinese export, particularly prized in England. The British East India Company purchased 27,000,000 pounds of tea in 1810, almost 10 times as much as the Americans. Crops of tea came into Canton over the months of the trading season. Merchants negotiated the best price and tried to ship it home as quickly as possible—freshness meant the highest profit. This is the only known painting to illustrate all phases of tea production. It is a “synoptic depiction” of Whampoa Island and the countryside, possibly Bohea Hills in Fukien Province, a primary tea producing area.

“The Production of Tea,” 1790–1800

Oil on canvas, unknown artist

Peabody Essex Museum [cwT_1790-1800_M25794] |

|

| |

The search for a commodity that the Chinese wanted to buy led the British to develop opium plantations in Bengal in India once they had secured control of it after 1757. The Americans found their opium source in Turkey, exported through the port of Smyrna. By the early 19th century, opium comprised a substantial portion of imports. It was illegal for the East India Company itself to deal in opium, but private British traders and the Americans developed extensive smuggling networks. For private traders, opium imports in 1828 were worth 11.2 million dollars, or 72% of total trade.

Trade goods in 1828 (in Mexican silver dollars)

British imports to Canton:

Woolens $1.7 million $1.7 million

Other Western goods $0.4 million $0.4 million

Imports from India:

Raw cotton $3.4 million $3.4 million

Opium $11.2 million $11.2 million

Sandalwood $0.12 million $0.12 million

Exports from Canton:

Tea $8.5 million $8.5 million

Silver $6.1 million $6.1 million

Raw silk $1.1 million $1.1 million

Although the primary profits of trade came from these basic commodities, every trader brought back, in addition to the tea and silk, artistic objects to demonstrate his taste or respond to demands from his family. Chinoiserie, or fascination with China, spread through 18th-century European literature and philosophy and expressed itself materially in the abundant artifacts produced in China for the foreign community.

|

|

Luxury Exports from China

|

| |

Teas, textiles, and common porcelains—the mainstay of the China trade—stimulated Western consumers’ appetites for more refined Chinese crafts. Chinese artisans modified traditional Chinese products to meet the demand. Luxury goods exported from China included fine porcelain, decorated specifically for Western taste and interests, figurines, and furniture. The porcelain and furniture, here shown with an images of Macau and Canton, gave Western consumers in Europe and America stylized images of a Chinese landscape that mixed fantasy and reality.

Porcelain Tureen with image of Canton [cwO_1780c_E80322]

Figure of a Mandarin (one of a pair) [cwO_E7097]

Lacquer image of Macau on a nesting table [cwO_1830-40_E82997b]

(other tables in these sets feature Canton & Bocca Tigris)

Peabody Essex Museum

|

|

| |

The luxury art objects generated images of China as a wealthy, refined, artistic civilization in the West. These objects inspired as much fantasy as reality. The landscapes on the porcelain dishes and lacquerware were highly stylized to blend Chinese and European aesthetic modes. The mandarin figurine pictured above depicts an official whom, under the restrictions of the Canton trade system, foreigners were almost never allowed to meet. The portrait below of the “Fou-yen of Canton” by William Alexander shows a high official in his imperial robes at a Western dining table, using a knife and fork, documenting an English banquet held during the 1793 diplomatic mission of Lord Macartney. It is unlikely that any Chinese official ever attended this kind of banquet again. In these objects, the Europeans and their Chinese producers created an imaginary cultural vision that combined what they wanted to select from each of their radically different traditions.

|

|

This curious image of a high Chinese official at an English banquet on January 8, 1794 was drawn by William Alexander, who accompanied Lord Macartney on this first British diplomatic mission to China. Most China traders never met a high Chinese official; they could only negotiate with the hong merchants. Macartney’s mission demanded access to imperial officials in order to negotiate freer trading conditions. He failed, but learned about the weaknesses of the Qing empire from his direct contact with these officials. This curious image of a high Chinese official at an English banquet on January 8, 1794 was drawn by William Alexander, who accompanied Lord Macartney on this first British diplomatic mission to China. Most China traders never met a high Chinese official; they could only negotiate with the hong merchants. Macartney’s mission demanded access to imperial officials in order to negotiate freer trading conditions. He failed, but learned about the weaknesses of the Qing empire from his direct contact with these officials.

“Portrait of the Fou-yen of Canton at

an English dinner,” January 8, 1794

by William Alexander

British Museum

[cwPT_1796_bm_AN166465001c]

|

|

|