| |

CULTURAL MOVEMENTS

In retrospect, one of the striking features of 1920s and 1930s Japan is the extent to which the rise of militarism took place in the midst of developments we now associate with an efflorescence of “modernity” worldwide in the early decades of the twentieth century, especially following World War I. Much of Japan, especially the economically less developed countryside, was indeed relatively backward—even, as Marxists then and later put it, “semi-feudal.” The counterpoint to this, however, was the conspicuous emergence of a consumer culture and popular mass culture that in many instances reflected cosmopolitan influences.

Although Tokyo and Osaka, Japan’s most vibrant metropolitan hubs, led the way in these developments, the allure of modernity penetrated provincial cities and seeped down to remote rural villages. One reason this happened so quickly was the revolution in mass communications. Public radio was introduced in the mid 1920s, and soon reached every corner of the country. The print media, stimulated by new production technologies, began addressing a mass audience through newspapers, magazines, and books aimed at carefully targeted readers. Cinema entered the scene, in the form of both imported foreign films and development of an indigenous industry. Popular theater flourished in the cities, including many adaptations of foreign playwrights.

Many of these developments moved in flashy and largely bourgeois directions—like the flourishing of “café culture” and the vogue of the “modern girl” and “modern boy,” all of which were transparently influenced by 1920s popular culture in the United States and Europe. From another direction, the devastating Kanto earthquake of 1923, which leveled most of Yokohama and a good part of Tokyo, had the ironically salutary effect of stimulating the reconstruction of a “new Tokyo” that was more Westernized and up-to-date than the ruined old city had been. Before the militarists took over, many observers regarded Japan as being embarked on a promising “modern” trajectory.

At the same time, this modernity obviously was riddled with contradictions. Inequalities in the distribution of wealth became more conspicuous, and large numbers of rural and working-class families could only look upon the material benefits of so-called progress with envy. Even here, however, the organizers of protest movements tapped into international trends for instruction and inspiration.

Unsurprisingly, they drew on ideas associated with the broad range of leftwing thought that had developed in the West—including Christian reformism; rightwing, moderate, and leftwing socialism; Marxism and hard-line Leninist communism; and eventually (and perversely) state-centered national socialism.

As the graphics in the Ohara collection remind us, these political and intellectual influences usually came wrapped in a distinctively cosmopolitan aesthetic sensibility that revealed, in this case, the influences of avant-garde and proletarian art.

|

|

|

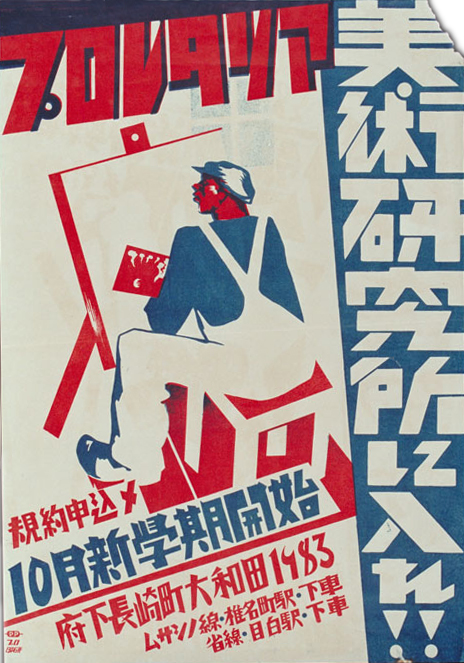

The bold text on this 1930 poster urges enrollment in the “proletarian”(red type) “Art Academy!!” (white on blue), where the new school year begins in October. Directions for the closest stations on two railway lines are given.

The bold text on this 1930 poster urges enrollment in the “proletarian”(red type) “Art Academy!!” (white on blue), where the new school year begins in October. Directions for the closest stations on two railway lines are given.

1930

[PA1048]

|

| |

Leftwing Publications

The relatively sophisticated textual content on interwar political graphics is a reminder of the fact that by this date the Japanese populace as a whole was impressively literate. This literacy traced back to educational reforms introduced in the latter half of the 19th century, and it extended to both blue-collar workers and farmers. As a consequence, leftist parties and labor-farmer associations generally churned out a variety of newsletters, newspapers, and magazines to keep their supporters up-to-date.

At the same time, the rise of a new urban intelligentsia was yet another familiar phenomenon of modernity. And a substantial portion of this intellectual production involved not only publishing original articles and books of a leftwing nature, but also translating many of the basic Marxist, socialist, and communist texts that defined radical thought in the Western tradition. Marx, Lenin, and a great many other radical theorists and polemicists all became accessible.

For the usual reasons, most periodicals associated with leftwing parties and unions were short-lived: government censorship and outright repression coupled with organizational infighting generally did them in. Nonetheless, some survived long enough to have an impact. Additionally, they were complemented and buttressed by another new genre of radical protest that emerged out of the social and economic turmoil of these years—namely, proletarian literature.

Proletarian literature made up almost half of the pages of the two largest magazines of the interwar period, Chūō Kōron (Central Review) and Kaizō (Reconstruction), while the two most successful leftist periodicals—Bungei Sensen (Literary Front) and Senki (Battleflag)—focused exclusively on proletarian literature and amassed a combined circulation of over 50,000 by 1930. Writers as diverse as Yumeno Kyūsaku, Umehara Hokumei, Hayashi Fumiko, and Ryūtanji Yū all published literary works that reflected concern for the “details of daily life under capitalism” and explored problems associated with industrialization, modernization, and urbanization.

The consolidation of three affiliated organizations—the Japan Proletarian Artists Alliance (Nihon Proletaria Geijutsu Renmei), the Labor-Farmer Artists Alliance (Rōnō Geijutsuka Renmei), and the Vanguard Artists Union (Zenei Geijutsuka Dōmei)—into the All-Japan Proletarian Art Federation (Zen Nihon Musansha Geijutsu Renmei) in 1928 enhanced the publication success of the movement’s most famous writers, Kobayashi Takiji and Tokunaga Sunao. In 1928 and 1929, the new federation’s journal Senki serialized two of Kobayashi’s most famous works. The first, titled March 15, 1928 and published in the November and December issues of that year, dealt with police torture following a draconian roundup of socialists and communists by the Home Ministry’s Special Higher Police (Tokubetsu Kōtō Keisatsu, commonly abbreviated as Tokkō and referred to as the thought police). In May and June of the following year, Senki published Kobayashi’s Crab-Cannery Ship (Kanikōsen), which focused on workers attempting to form a union in the fishing industry; this provocative novella was adapted as a theatrical performance that same year. In 1929, Senki also serialized Tokunaga’s most famous novel, Street Without Sun (Taiyō no nai Machi), which focused on workers struggling for their rights and was quickly adapted as a stage presentation.

|

|

|

| |

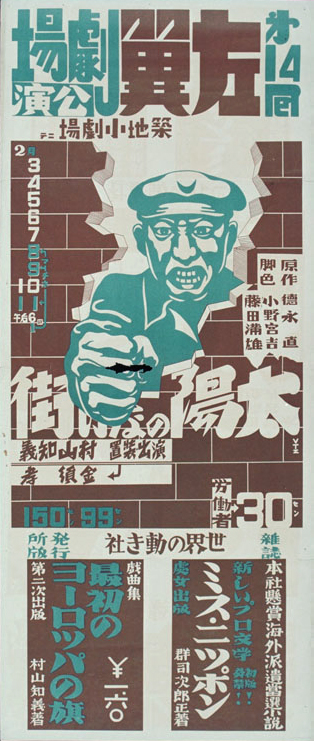

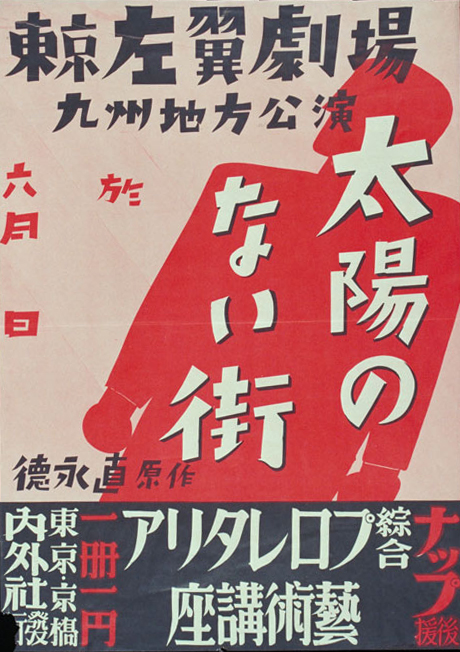

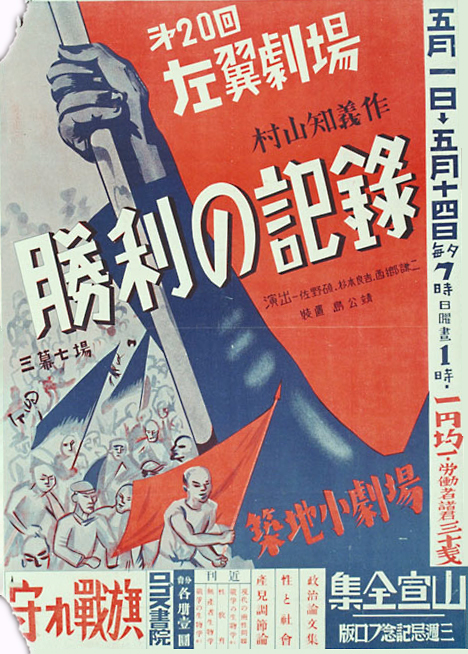

Both of these posters from 1930 advertise theatrical adaptations by the Tokyo-based Leftwing Theater (Sayoku Gekijō) of Tokunaga Sunao’s 1929 proletarian novel Street Without Sun. The militant presentation on the left was directed by the protean artist/writer/director Murayama Tomoyoshi. (The two squares at the bottom advertise books, including on the left a collection of plays authored by Murayama.) The poster on the right advertises a Leftwing Theater performance in the southernmost island of Kyushu.

1930 [PA0946] [PA1014]

|

|

| |

Although Kobayashi himself escaped the notorious “March 15 Incident” he excoriated in his 1928 rendering, this was a great turning point for political activists. Faced with the prospect of imprisonment and torture, many leftists then or soon afterwards publicly announced the recantation (tenkō) of their beliefs—a largely collective act that has haunted the political left in Japan ever since. Tokunaga more or less recanted in 1933. Kobayashi did not, and in that same year, at the age of 29, he paid the price for commitment to his ideals. He was arrested for being affiliated with the outlawed Japan Communist Party and died after being tortured by the same “thought police” he had criticized five years earlier.

In perusing the Ohara collection of protest graphics, it is helpful to keep such intimate vignettes in mind.

|

|

|

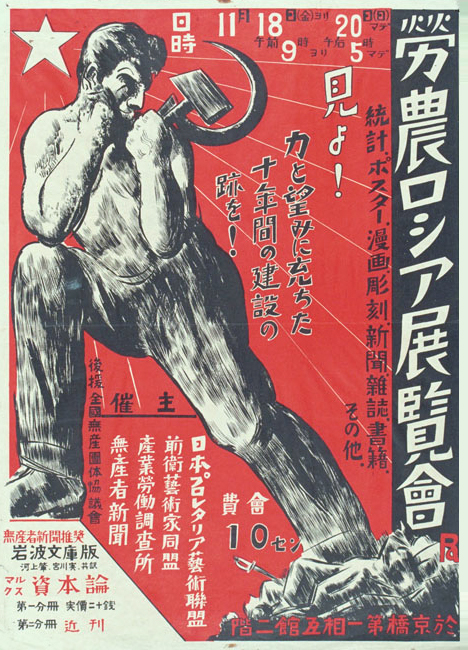

Sponsored by several leftist organizations, this November 1927 poster announces a “Labor-Farmer Russia Exhibition” commemorating the “power and hope” of the tenth anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution. Small type in the lower left corner advertises the Iwanami publishing house’s translation of Karl Marx’s Das Kapital.

Sponsored by several leftist organizations, this November 1927 poster announces a “Labor-Farmer Russia Exhibition” commemorating the “power and hope” of the tenth anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution. Small type in the lower left corner advertises the Iwanami publishing house’s translation of Karl Marx’s Das Kapital.

1930

[PA1053]

|

|

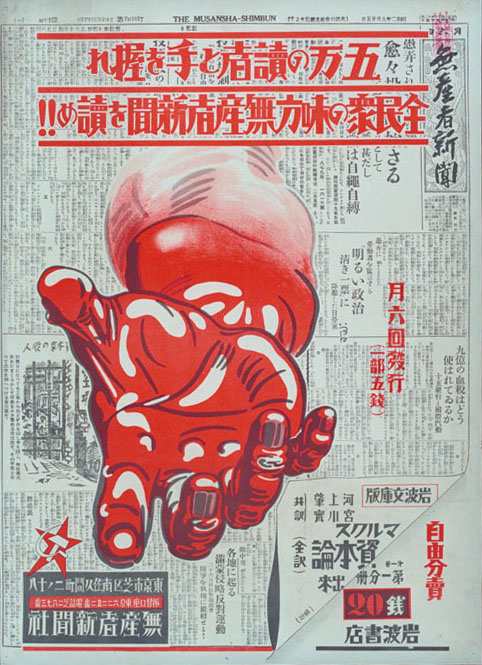

The red banner headline on this 1927 advertisement reads “Join hands with 50,000 readers. Read the Proletarian Newspaper (Musansha Shimbun), the ally of the people!!” Smaller red text notes that the newspaper is published six times a month and costs five sen. The ad also publicizes “Marx’s Das Kapital, translated by Kawakami Hajime and Miyagawa Minoru. Sold separately. Price: 20 sen.” Kawakami, who was strongly influenced by Tolstoy and Christian socialism in his youth, emerged as one of Japan’s most influential Marxist intellectuals in the 1920s and was imprisoned between 1933 and 1937 for his pro-communist activities.

The red banner headline on this 1927 advertisement reads “Join hands with 50,000 readers. Read the Proletarian Newspaper (Musansha Shimbun), the ally of the people!!” Smaller red text notes that the newspaper is published six times a month and costs five sen. The ad also publicizes “Marx’s Das Kapital, translated by Kawakami Hajime and Miyagawa Minoru. Sold separately. Price: 20 sen.” Kawakami, who was strongly influenced by Tolstoy and Christian socialism in his youth, emerged as one of Japan’s most influential Marxist intellectuals in the 1920s and was imprisoned between 1933 and 1937 for his pro-communist activities.

1927

[PA0577]

|

|

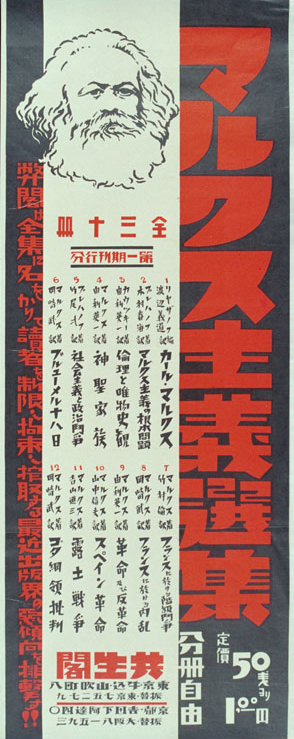

This 1928 advertisement for a 30-volume collection of Marxist writings offers individual volumes priced between 50 sen and one yen.

This 1928 advertisement for a 30-volume collection of Marxist writings offers individual volumes priced between 50 sen and one yen.

1928

[PA0966]

|

|

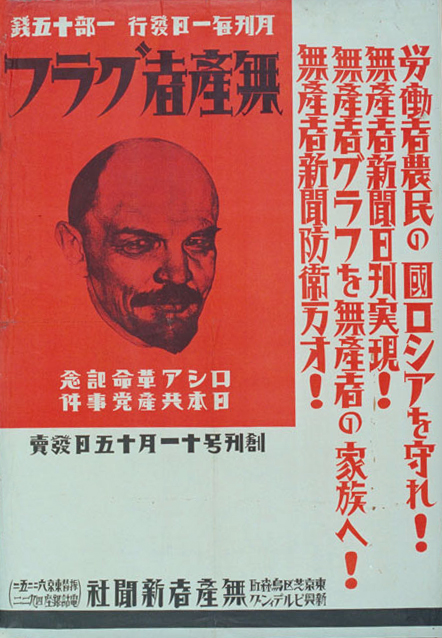

Issued by the publisher of the Proletarian Newspaper, this ad for the November 1928 issue of the monthly Proletarian Graphic (Musansha Gurafu) features a portrait of Lenin and these exclamations:

Issued by the publisher of the Proletarian Newspaper, this ad for the November 1928 issue of the monthly Proletarian Graphic (Musansha Gurafu) features a portrait of Lenin and these exclamations:

“Protect Russia, land of workers and farmers!”

“Make a daily proletarian newspaper a reality!”

“Distribute the Proletarian Graphic to a proletarian family!”

“Long Live the Defense of the Proletarian Newspaper!”

1928

[PA0583]

|

|

Beneath the familiar broken chain of worker servitude, the heading of this 1927 advertisement reads: “Read the Proletarian Newspaper!” Text to the right and left of the militant worker steering the ship of revolution translates as “Ally of the people” (right) and “Our political newspaper” (left).

Beneath the familiar broken chain of worker servitude, the heading of this 1927 advertisement reads: “Read the Proletarian Newspaper!” Text to the right and left of the militant worker steering the ship of revolution translates as “Ally of the people” (right) and “Our political newspaper” (left).

1927

[PA0521]

|

|

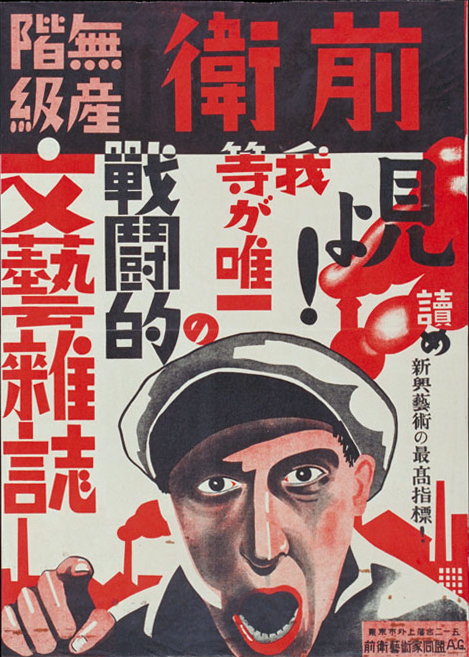

A worker with a smoke-belching factory behind him solicits readers for the monthly Zenei (Vanguard), which was produced by the outlawed Japan Communist Party. “Look!” this 1928 advertisement exclaims, “we are the only combative proletarian arts magazine.” Smaller type in black spells out “Read the best guide to new art!”

A worker with a smoke-belching factory behind him solicits readers for the monthly Zenei (Vanguard), which was produced by the outlawed Japan Communist Party. “Look!” this 1928 advertisement exclaims, “we are the only combative proletarian arts magazine.” Smaller type in black spells out “Read the best guide to new art!”

1928

[PA1075]

|

|

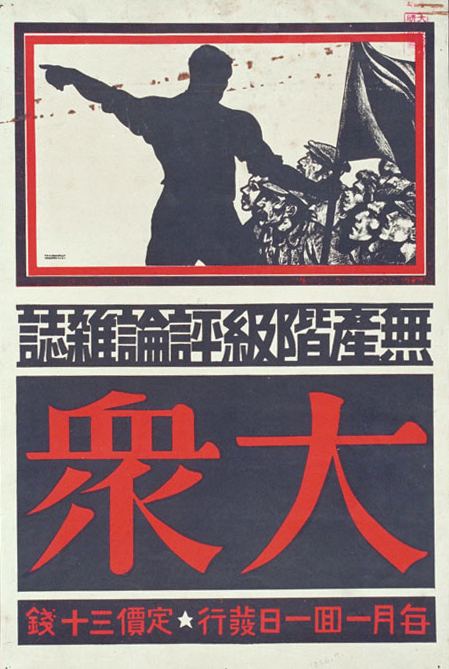

This 1929 advertisement for the monthly Taishū (The Masses) declares this to be “The critical discussion magazine of the proletarian class.” This 1929 advertisement for the monthly Taishū (The Masses) declares this to be “The critical discussion magazine of the proletarian class.”

1929

[PA1073]

|

|

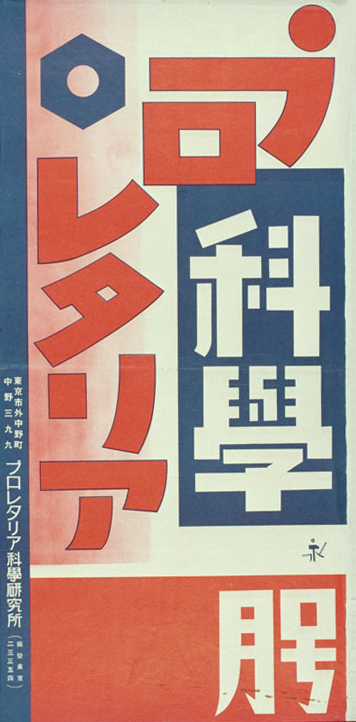

Stylish modernistic typography distinguishes this late 1920s cover of the journal Proletarian Science (Puroretaria Kagaku). The journal was published by the Proletarian Science Research Institute (Puroletaria Kagaku Kenkyūjo), which rendered “proletarian” in phonetic script rather than the three-ideograph compound (musansha) used in other radical publications like the Proletarian Newspaper.

Stylish modernistic typography distinguishes this late 1920s cover of the journal Proletarian Science (Puroretaria Kagaku). The journal was published by the Proletarian Science Research Institute (Puroletaria Kagaku Kenkyūjo), which rendered “proletarian” in phonetic script rather than the three-ideograph compound (musansha) used in other radical publications like the Proletarian Newspaper.

late 1920s [PA0964]

|

|

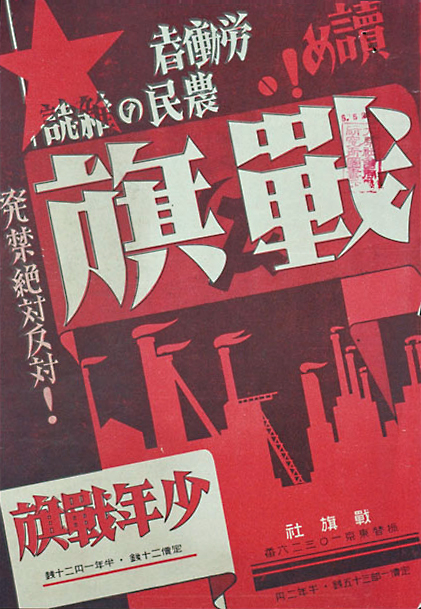

The exhortation on this assertively red-colored advertisement translates as “Read the workers’ and farmers’ magazine Battleflag (Senki),” while the vertical writing on the left declares “Absolutely opposed to suppression!” The white box at bottom left advertises a companion youth-oriented journal, Youth Battleflag (Shōnen Senki). Senki was a major vehicle for writers affiliated with the proletarian literature movement, and the 1930 date of this graphic is revealing. It follows by two years the Home Ministry crackdown on leftwing activists and writers—the “March 15 Incident”—critically novelized (on Senki’s pages) by the courageous writer Kobayashi Takiji, who was beaten to death by the thought police in 1933. The exhortation on this assertively red-colored advertisement translates as “Read the workers’ and farmers’ magazine Battleflag (Senki),” while the vertical writing on the left declares “Absolutely opposed to suppression!” The white box at bottom left advertises a companion youth-oriented journal, Youth Battleflag (Shōnen Senki). Senki was a major vehicle for writers affiliated with the proletarian literature movement, and the 1930 date of this graphic is revealing. It follows by two years the Home Ministry crackdown on leftwing activists and writers—the “March 15 Incident”—critically novelized (on Senki’s pages) by the courageous writer Kobayashi Takiji, who was beaten to death by the thought police in 1933.

1930

[PA1043]

|

|

| |

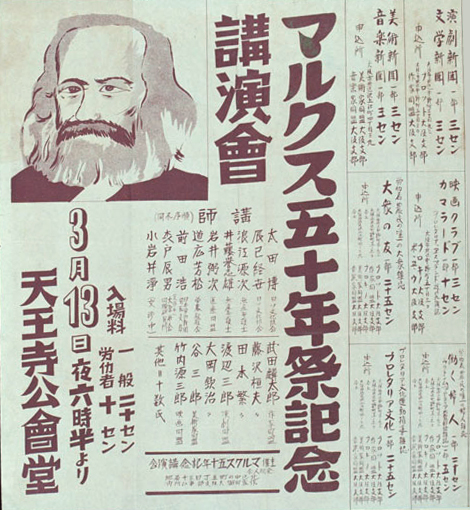

This advertisement invites people to a public assembly on March 13, 1933 at Tenōji Meeting Hall in Osaka to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Marx’s death. (Marx died on March 14, 1883 London time.) Sixteen speakers are listed, and the entrance fee is 20 sen, but half that price for workers.

The fine print on the right itemizes publications aimed at the progressive audience to whom the advertisement is directed, and gives a fair impression of the struggle of leftwing publishers to survive even after the intensification of censorship and the military takeover of Manchuria in 1931.

The various titles (with prices given for each) translate as “Theater News,” “Literature News,” “Art News,” “Music News,” “Film Club,” “Comrade,” “Friend of the Masses,” “Working Women,” and “Proletarian Culture.”

1933 [PA1043]

|

|

| |

Political Theater

The introduction of European-style theatrical modernism in Japan can be dated quite precisely to the immediate wake of the Russo-Japanese War in the early years of the 20th century. An Ibsen Society was founded in 1907, for example, and a 1911 production of Ibsen’s A Doll’s House galvanized formation of the Blue Stocking Society (Seitō), a pioneer voice in the Japanese woman’s movement, that same year.

The modern theater movement took the generic name Shingeki (New Theater), and the infusion of Western influences increased exponentially following World War I and the Bolshevik Revolution. Expressionism, dadaism, and constructivism all impacted the Japanese theater world. So also, predictably, did proletarian literature and stagecraft. In 1924, the year following the Kanto earthquake, the Tsukiji Little Theater (Tsukiji Shōgekijō) was founded in Tokyo with an original commitment to produce only plays by foreign authors. Their impressive offerings included works by Anton Chekhov, Maurice Maeterlinck, Maxim Gorky, Upton Sinclair, George Bernard Shaw, August Strindberg, Roman Rolland, and Luigi Pirandello.

|

|

|

| |

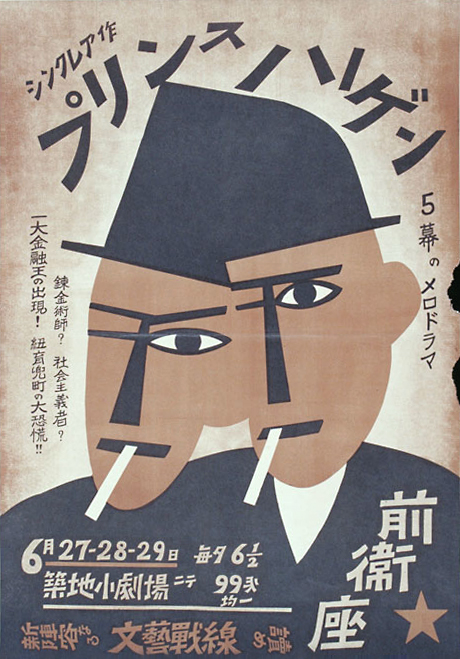

This 1929 advertisement for Prince Hagen, “a melodrama in five acts” by Upton Sinclair, conveys some of the confrontational élan of the leftwing theatrical world. Presented by the Vanguard Theater Group (Zeneiza) at the Tsukiji Little Theater in Tokyo in the year following the government’s notorious “March 15” crackdown on leftists, the mildly surreal rendering of Sinclair’s protagonist is flanked by phrases reading “Alchemist?” “Socialist?” The emergence of a great king of finance!” “The terror of Wall Street!” The bottom line is an advertisement for the periodical Literary Front (Bungei Sensen).

1929 [PA1019]

|

|

| |

Typically, factionalism coupled with mounting repression fractured the modern theater movement and culminated in its dissolution by the end of the 1930s. In 1928, the Tsukiji Little Theater split into “political” and “literary” factions, for example, and in 1940 government oppression culminated in a mass arrest of around 100 individuals associated with leftwing theater. As elsewhere on the left, many beleaguered theatrical activists ultimately recanted and redirected their activities to support of the “holy war.” At the same time, however, and also typically, this brief but intense interwar engagement in critically addressing contemporary problems had a profound influence on the reemergence of politically and socially concerned theater in the years following Japan’s defeat in 1945.

The prewar career of Murayama Tomoyoshi provides a vivid impression of the complex and interactive dynamics of the proletarian art, literature, and theater movements. A Christian convert who studied art and drama in Berlin in the early 1920s, Murayama quickly made a name for himself as a leader of the avant-garde MAVO art movement while also extending his vision and energy to theater writing, directing, set design, and even occasional acting. His theatrical productions included Marxist renditions of “Robin Hood” and Don Quixote. In 1929, he acted in the Tokyo stage production of Tokunaga’s proletarian novella Street Without Sun and also designed the set for a Japanese adaptation of Danton’s Death, a 1835 play about the French Revolution by the precocious German playwright Georg Buchner. (Buchner was only 23 when he died of typhus in 1837.)

Murayama was arrested in May 1930 and charged with violating the Peace Preservation Law. Released in December, he immediately and provocatively joined the outlawed Japan Communist Party, which led to his rearrest and imprisonment in 1932. He was released from prison in 1934 after ostensibly recanting his leftist positions, but continued to produce dramatic work critical of the militarist state—leading to interludes of incarceration in 1940-42 and again in 1944-45. Unlike his contemporary Kobayashi Takiji, the proletarian writer who died in the hands of the police after being arrested, Murayama survived the war to participate actively in the turbulent—and, again, fractious—postwar scene. He died in 1977, at the age of 76. The following theater posters from the Ohara collection all involve Murayama in one way or another.

|

|

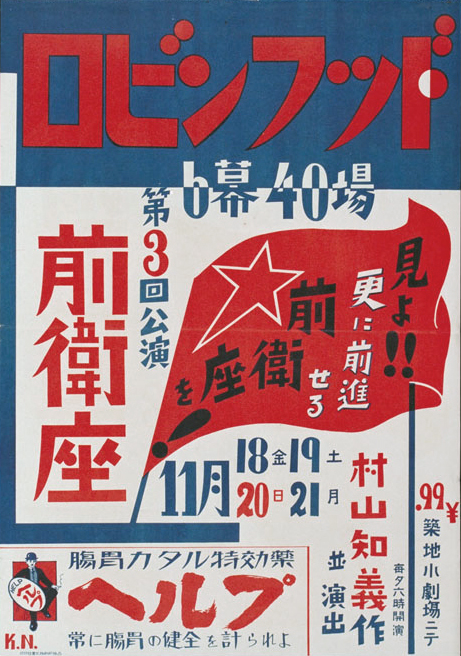

Familiar red lettering dominates this late 1920s poster advertising a production of Robin Hood written and directed by Murayama Tomoyosh, and presented “in six acts and 40 scenes” by the Vanguard Theater Group at the Tsukiji Little Theater. Familiar red lettering dominates this late 1920s poster advertising a production of Robin Hood written and directed by Murayama Tomoyosh, and presented “in six acts and 40 scenes” by the Vanguard Theater Group at the Tsukiji Little Theater.

[PA1043]

|

|

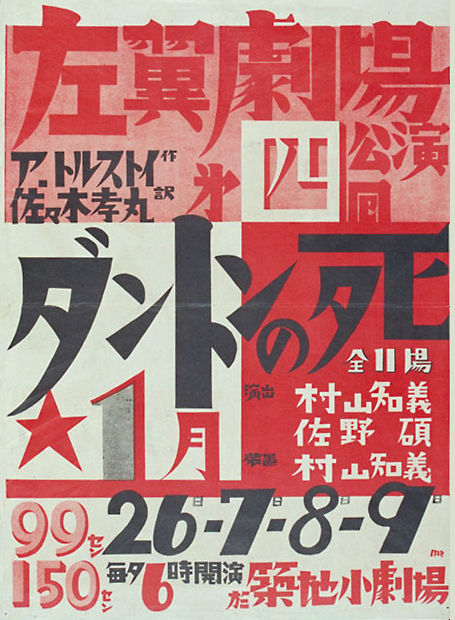

Presented by the Leftwing Theater group at the Tsukiji Little Theater in 1929, this production of Danton’s Death by Aleksei Tolstoy was codirected by Murayama Tomoyoshi, who also did the staging. Presented by the Leftwing Theater group at the Tsukiji Little Theater in 1929, this production of Danton’s Death by Aleksei Tolstoy was codirected by Murayama Tomoyoshi, who also did the staging.

1929

[PA1008]

|

|

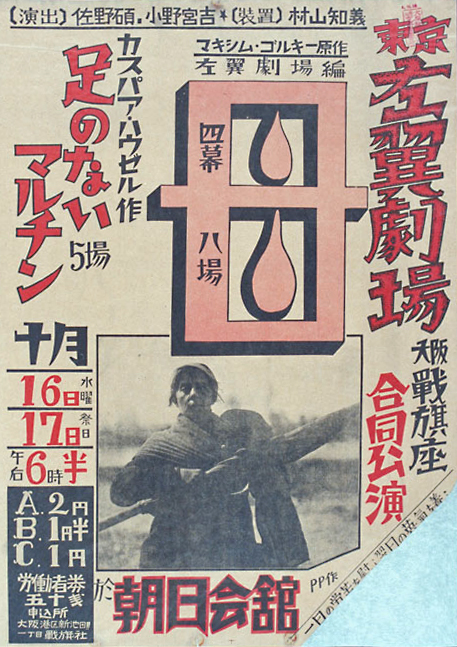

This presentation of several dramas jointly performed by Tokyo’s Leftwing Theater and the Osaka Battleflag Group (Osaka Senkiza) features Maxim Gorky’s four-act play The Mother. The staging is by Murayama Tomoyoshi. This presentation of several dramas jointly performed by Tokyo’s Leftwing Theater and the Osaka Battleflag Group (Osaka Senkiza) features Maxim Gorky’s four-act play The Mother. The staging is by Murayama Tomoyoshi.

1929

[PA1009]

|

|

The Leftwing Theater group here advertises a two-week run of Murayama Tomoyoshi’s drama Record of Victory (Shōri no Kiroku) at the Tsukiji Little Theater in May 1931. Tickets for workers are one-third the price of regular admission. This graphic depiction of militant workers carries particular resonance in retrospect, since it was only four months later, in mid September, that the so-called Manchurian Incident took place, signaling a disastrous new stage in Japanese aggression against China. The Leftwing Theater group here advertises a two-week run of Murayama Tomoyoshi’s drama Record of Victory (Shōri no Kiroku) at the Tsukiji Little Theater in May 1931. Tickets for workers are one-third the price of regular admission. This graphic depiction of militant workers carries particular resonance in retrospect, since it was only four months later, in mid September, that the so-called Manchurian Incident took place, signaling a disastrous new stage in Japanese aggression against China.

1930

[PA1013]

|

|

|