| |

FARMERS’ MOVEMENTS

As indicated in the post-World War I proliferation of “labor-farmer” political parties, opposition movements by an emerging urban working class were complemented by leftwing protests aimed at mobilizing impoverished farmers in the countryside.

Following the Meiji Restoration of 1868, which overthrew the samurai-dominated feudal system that had governed the country for eight centuries, Japan’s leaders embarked on a path of Westernization and industrialization that privileged the urban sector over the more backward agrarian economy. The new modernizing state was heavily dependent on taxes disproportionately extracted from the rural sector, and many farmers were hard pressed to make ends meet. As time passed, the plight of many of them became worse rather than better.

Whereas World War I stimulated a war boom in Japan’s industrial sector, it simultaneously brought greater setbacks to much of the rural political economy. Land rents as well as the costs of tools and fertilizer accelerated the descent of many small land holders into foreclosure and tenancy. Higher rents exacted in kind by an emerging cadre of new landlords forced the swelling class of tenant farmers into the position of having to buy rice to feed their families.

Hunger followed mounting poverty closely, and was among the major reasons behind the rural unrest that culminated in the nationwide rice riots of 1918. Although the government interceded by cutting the price of rice in half, price controls evaporated when economic recession hit Japan in the early 1920s. The recession exacerbated rural hardship, and one conspicuous result of this was a mounting exodus of poor farmers who migrated to the cities to seek factory work. With the onset of the Great Depression in 1929, rural Japanese suffered a further blow from the collapse of the export market for silk, which was one of the major by-employments that farm families had relied on for supplemental income.

Many political activists devoted themselves to organizing grassroots associations of poor farmers; and more than a few espoused the necessity of forging strong labor-farmer alliances. Beginning in 1921 and continuing into the early 1940s, the number of outright tenancy disputes numbered over 1,500 annually—reaching an annual peak of around 6,000 in the mid 1930s. However one might break down these numbers, they were certainly sufficient to alarm the ruling elites—especially when paired with tandem incidents of protest by urban workers.

Beginning in the 1920s, activists and organizers spanning a broad ideological spectrum devoted attention to rural problems and the desirability of building bridges between poor farmers and blue-collar workers. By the early 1930s, their factionalism mirrored the fratricidal rifts that plagued the urban labor movement and precipitated the splintering of the movement into eleven “proletarian” parties, several of which included “farmer” in their names. Centrist and rightwing socialists vied with hard-line communists; parties changed their names with bewildering speed; and by the mid 1930s, as everywhere on the left, many erstwhile socialists found it expedient to change their colors to “national socialist” and throw their support behind the militarists and their expansionist agenda.

Still, the longer-term legacy of rural unrest was substantial. To a very considerable degree, sweeping land-reform legislation introduced by U.S. occupation reformers following Japan’s defeat in 1945 was motivated by fear that, absent such reform, the countryside might well erupt in “Red” revolution.

Posters in the Ohara collection that focus on interwar discontent in the countryside give a fair sense of why such fears arose.

|

|

|

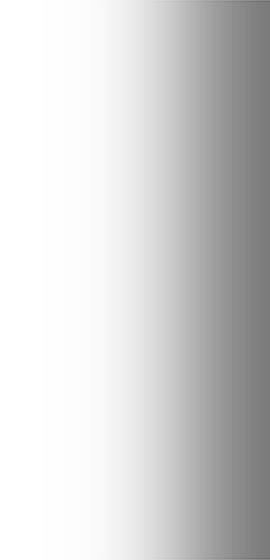

1927

The shirt of this axe-wielding farmer reads “Japan Farmers’ Party ”(Nihon Nōmintō), and the ball chained to the bicycle is labeled “Unfair taxes.” The explanatory text reads as follows:

Heavy taxes amounting to 40 million yen are attached to the legs of farmers, laborers, government functionaries, and petty merchants. More than four million riders all over the country are suffering from this unfair tax.

Let’s push to abolish the bicycle tax.

The tax on bicycles was but one of many onerous burdens imposed on the lower classes.

[PA0635]

|

Previous | Next Previous | Next |

|

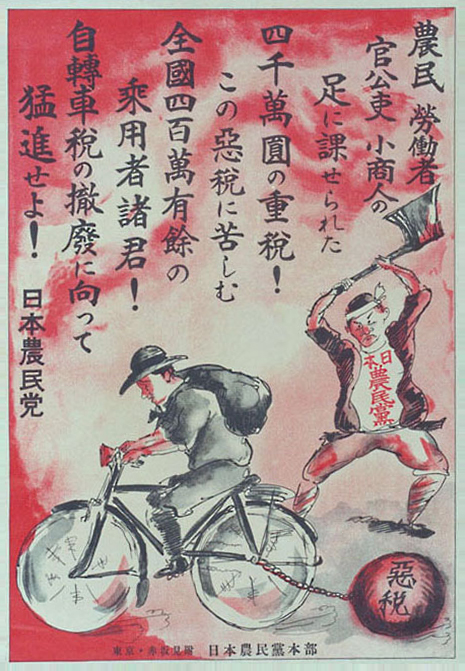

1928

A militant farmer holding a scythe in one hand and red flag in the other urges landless farmers to attend an August meeting of the National Farmers’ Union (Zenkoku Nōmin Kumiai) in Niigata prefecture. This union emerged out of factional squabbles in 1928 and survived until 1938. The heading at the top addresses “Proletarian farmers of the entire prefecture!!” Text elsewhere urges them to “Unite” and “Fill the entire prefecture with the flag of the union.” Like the scythe, the red flag, and the militant male activist, the silhouette of protestors marching over an uneven terrain is another example of the formulaic imagery that distinguishes many of these radical graphics.

[PA0913]

|

Previous | Next Previous | Next |

|

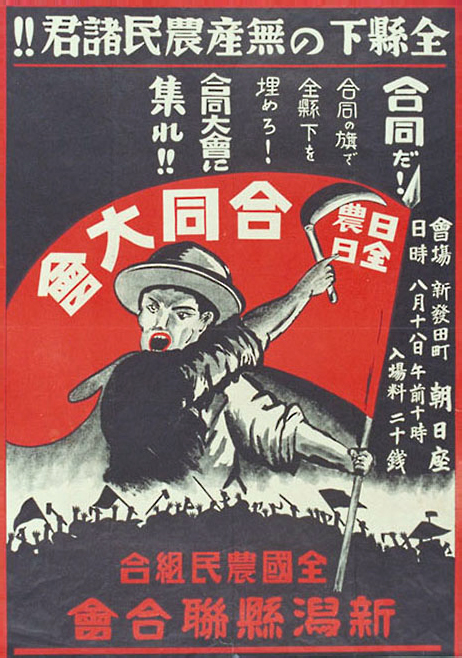

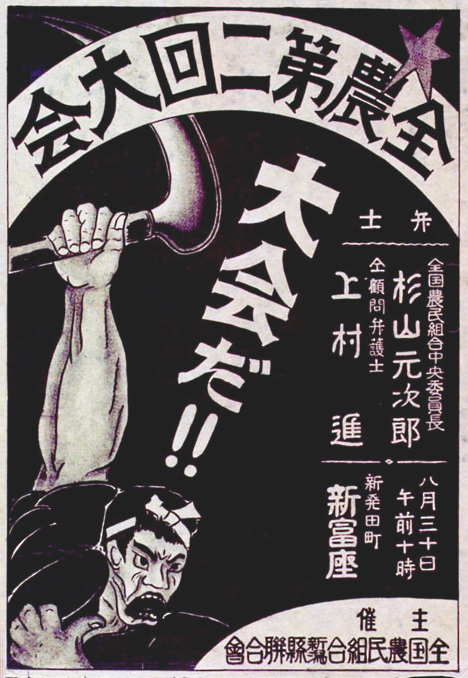

1929

This muscular scythe-wielding farmer is announcing the second annual meeting of the National Farmers’ Union.

[PA2337]

|

Previous | Next Previous | Next |

|

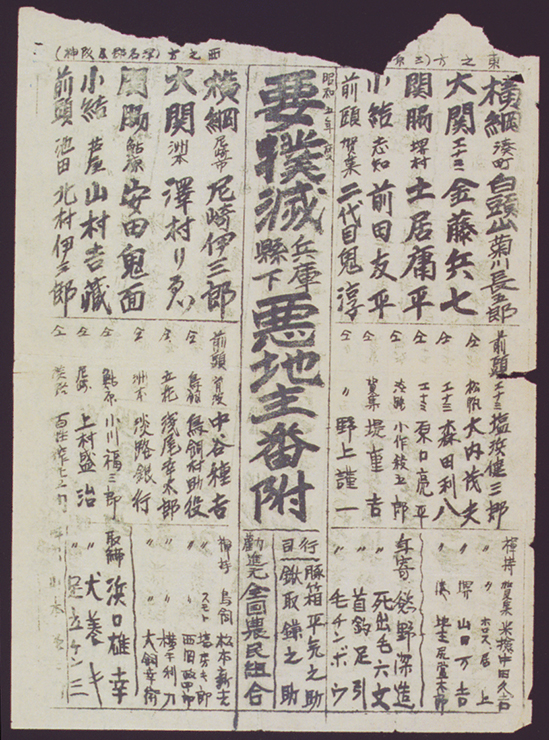

1930

This witty graphic mimics the lineup of a sumo tournament, with a heading that reads “ranked list of bad landlords in Hyōgo prefecture who should be defeated.” The list assigns the top four ranks in the sumo hierarchy to the “bad” landlords; the “promoter” of the confrontation is identified as the National Farmers’ Union; and most of the names of officials listed at the bottom are satirical (such as “Stingy Fellow”).

[PA2458]

|

Previous | Next Previous | Next |

|

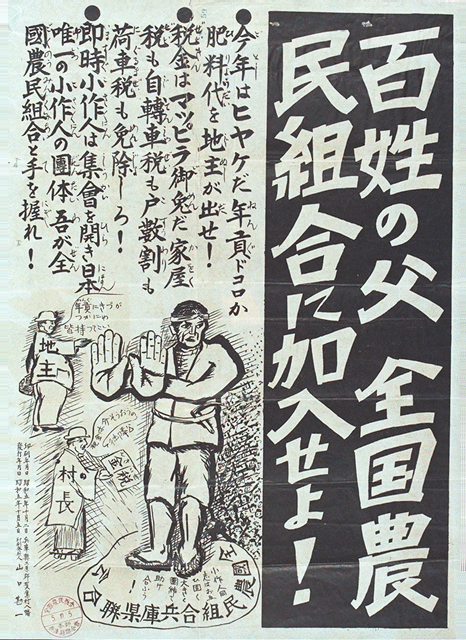

1929

The bold text reads: “Join the National Farmers’ Union, the father of the farmers!” The small figures being repulsed by a union-affiliated farmer represent landlords (top) and village heads (bottom), and the bill being presented by the latter reads: “tax.” The union’s demands:

This is a drought year. Contrary to collecting rent, landlords should pay for our fertilizer.

Down with these taxes! We want exemptions from the property tax, bicycle tax, frontage tax, and wagon tax!

Tenant farmers should immediately hold an assembly and join hands with the National Farmers’ Union, Japan’s only tenants’ association!

[PA0930]

|

Previous | Next Previous | Next |

|

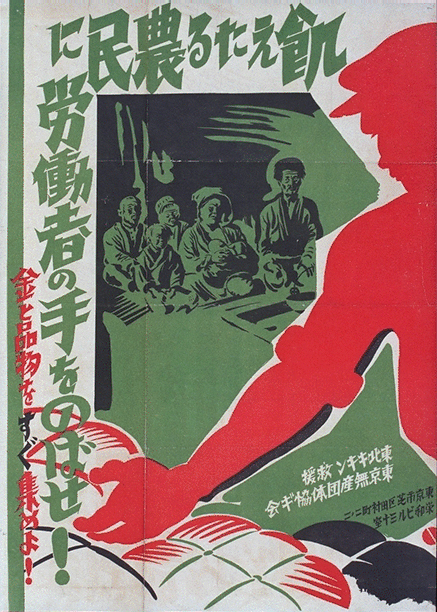

1931

Between 1931 and 1934, the rural population in the northern prefecture of Tōhoku was ravaged by a famine that was disastrously compounded by a devastating earthquake and tsunami in March 1933. This 1931 poster exhorts urban laborers to “Extend the workers’ hands to the starving farmers” by immediately donating money and supplies. The campaign is sponsored by an ad hoc Tokyo Proletarian Groups Coalition.

[PA0895]

|

Previous | Next Previous | Next |

|

1935

This banner announces the “fourteenth” congress of the National Farmers’ Union, scheduled for April 6 to 8. By this date, most such organizations had thrown their support behind Japan’s military expansion and looked to the government to alleviate their socio-economic difficulties through some form of national socialism.

[PA0048]

|

Previous | Return Previous | Return |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|