|

| |

LOOKING & LOOKING BACK

The U.S. imperial agenda that emerged from the Spanish-American War in 1898 was always controversial and critics of American colonial policy continued to voice their concerns. Many focused their attention on Dean Worcester, a vigorous supporter of U.S. policy in the Philippines and temperamentally one of the most divisive figures in the islands. James H. Blount, a vocal anti-imperialist, questioned Dean Worcester’s pretensions to scientific authority and mocked him for “discovering, getting acquainted with, classifying, tabulating, enumerating, and otherwise preparing for salvation, the various non-Christian tribes.” Blount felt that Worcester used photography to manipulate both Filipino subjects and American readers, trying to convince both groups that the Philippines was unprepared for political independence. “Professor Worcester,” he wrote, “is the P.T. Barnum of the ‘non-Christian tribe’ industry.” [1]

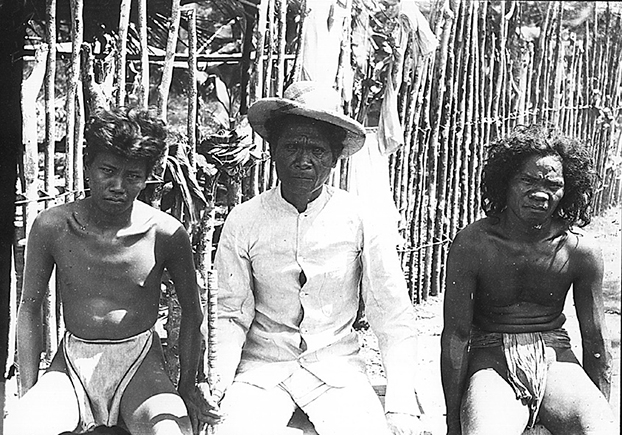

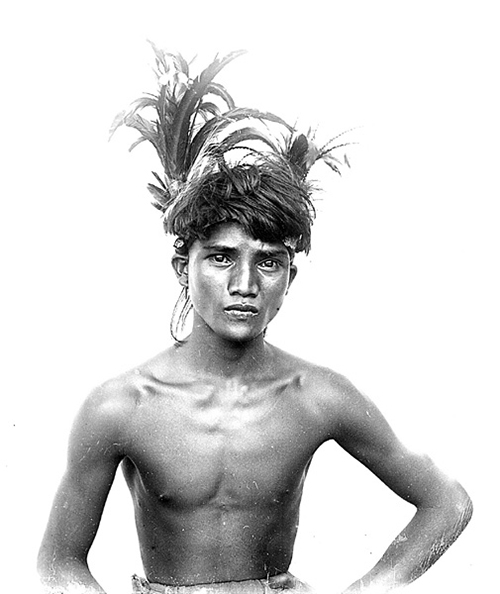

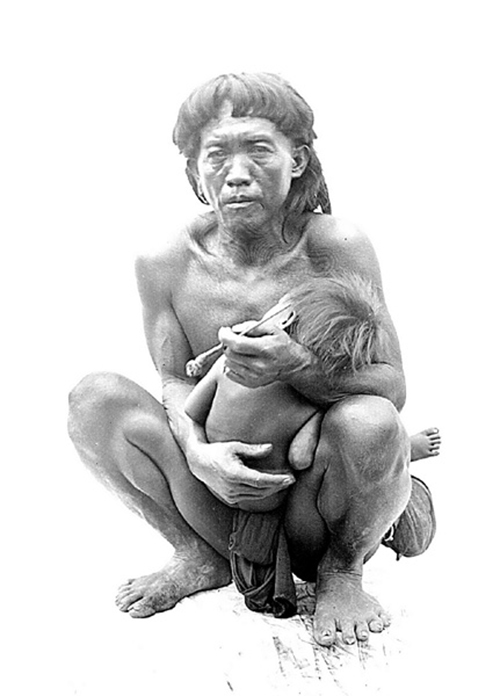

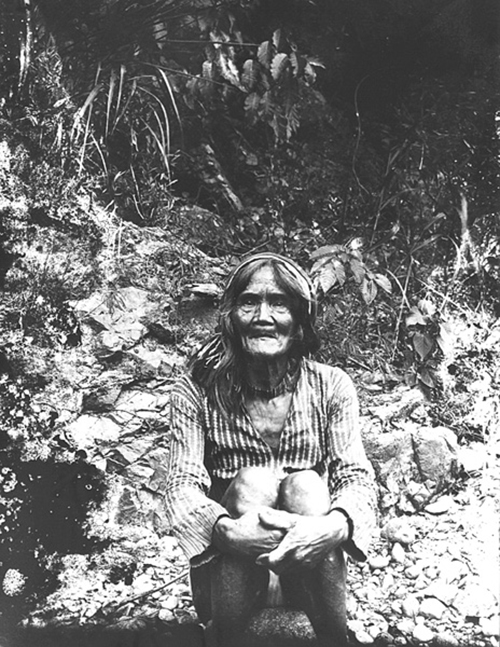

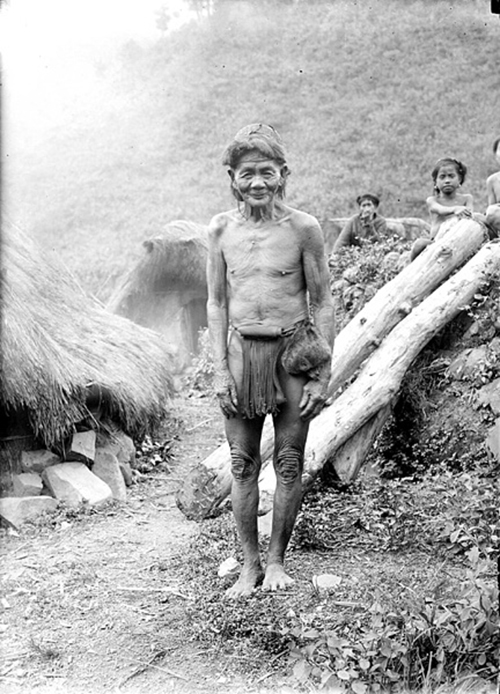

We know very little about the men and women who sat for Dean Worcester’s camera. Most of them could not read or write, and so a century later we are left to decipher their emotions and motivations from the images themselves.

Many of the images feature defiant resistance, sullenness, evasion, even obvious boredom; a stubborn refusal to look at the photographer; or a testy stare directly back at the camera and the political power that it embodied. There were few options for the residents of the hill tribes who posed for Worcester and his companions, but the photographs show their efforts to act, even within that limited range.

|

|

|

| |

We know little about what the men and women who sat for Worcester’s photographs thought about the experience. We do know that some opposed his efforts, and in images such as this, it is possible to imagine how resistance, boredom, or testiness might have made their way into the photographic archive.

Worcester’s caption: “Group of three Tagbanua men.

Half length front view,” 1905

[dw04B001]

|

|

| |

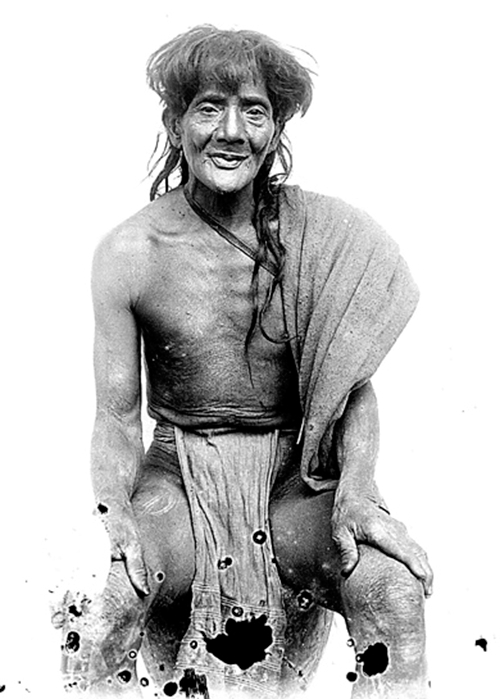

Some responded well, and evidence shows that Worcester’s photo-making was often a collaborative undertaking. In his diary on February 7, 1901, he wrote that he “Made one print from each negative before breakfast in order to show them to the Igorrotes,” suggesting a willingness to engage in dialogue with his photographic subjects. The next day, he noted in his diary that he had “Made prints of negatives before breakfast, so as to give them to the Igorrotes, who were much pleased with them.” [2]

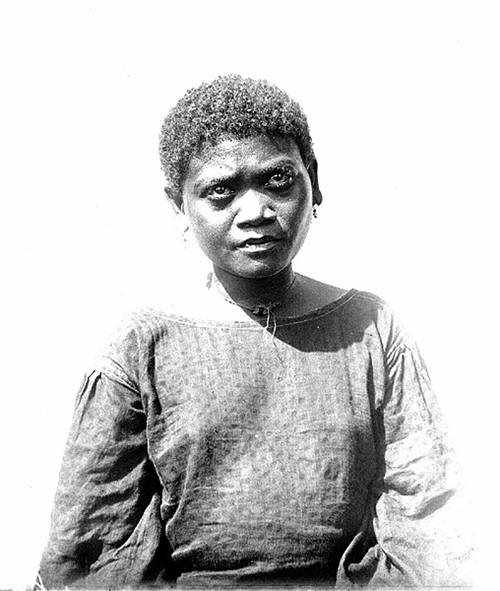

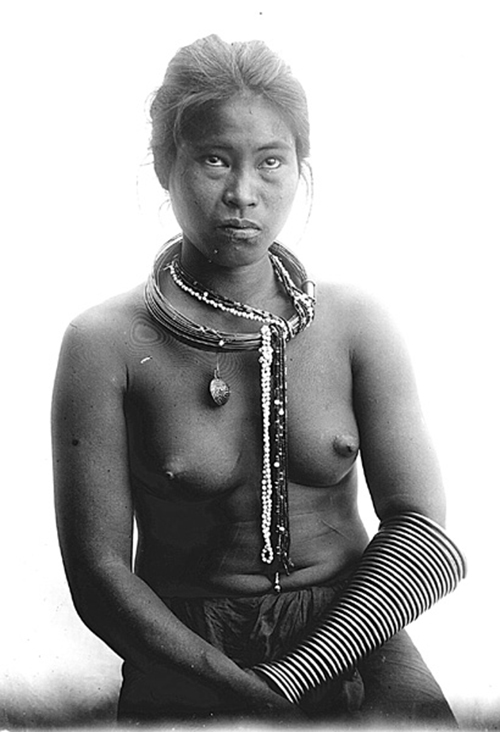

But from Worcester’s own writings, we know that some Filipinos did not appreciate his efforts to photograph them, and sometimes his relationships with sitters were less egalitarian.

|

|

|

“This girl was badly frightened,” Worcester noted in reference to the photo on the left.

Images such as this highlight the power of the photographer over the sitter. And the role of the viewer: when reproduced and distributed, such images conveyed messages about the Filipino as “primitive” without calling into question the right of the photographer to take pictures of unwilling subjects.

Worcester’s caption: Bontoc Igorot girl, 1903.

Location: Mayinit, Bontoc

[dw08C008] |

| |

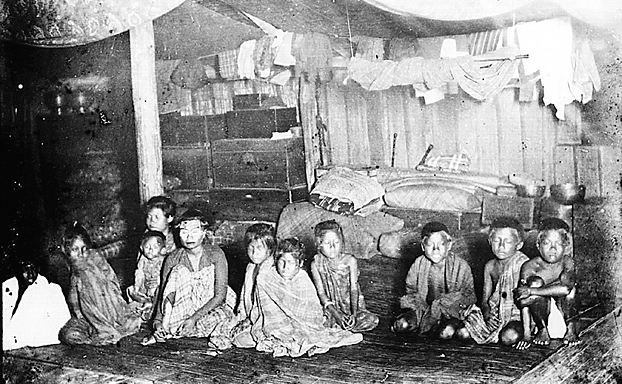

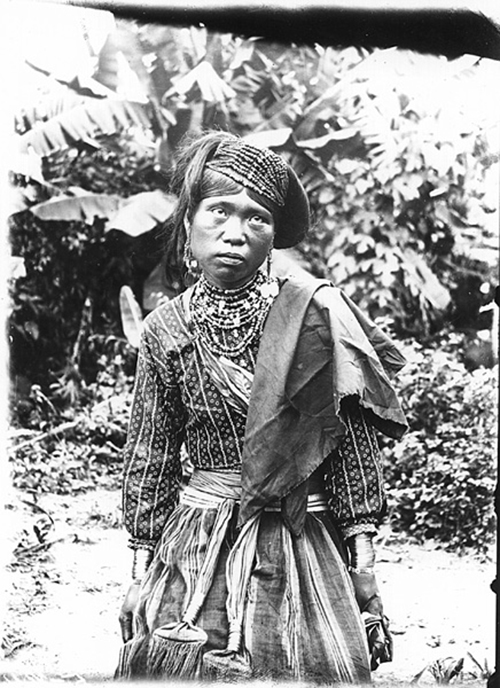

Worcester wrote of the Muslim inhabitants of the southern Philippines,

We had great difficulty in getting photographs of the Moros. They were unduly influenced by the remarks in the Koran concerning the making of pictures of living things…. We were obliged to steal most of our pictures, and we found it difficult and dangerous work….

Worcester occasionally used deception to get hold of his photographs. Attending a Moro wedding in one of his early voyages in the early 1890s, he noted:

[w]e were very anxious to get pictures of the guests, and that evening smuggled in our dismounted camera, together with some magnesium powders and a flashlight lamp. Under pretext of contributing our share to the entertainment, we showed them how to make artificial lightning. Bourns focussed by guess, I touched off magnesium powders, and in this way we made a number of exposures, only two of which gave us negatives that would print. [3]

Worcester’s blurry photograph appears below. |

|

|

| |

This overexposed photograph is one of the earliest in the Dean Worcester collection, taken on his trip to the Philippines in 1891. In his writings, Worcester explained how he and fellow traveler Frank Bourns schemed to photograph these pious Muslims without their consent. According to Worcester, this group of guests at a wedding in the Sulu province did not know that they were being photographed.

Worcester’s caption: “Interior of a Moro house with a woman and girls in the foreground,” 1891. Location: Jolo, Sulu

[dw23D029]

|

|

| |

Filipinos also resisted Worcester’s Kodak by using the limited powers that were available to them in the political arena. In 1907, in an effort to co-opt political opposition in the islands and to delegate some of the routine tasks of governance, the U.S. established the Philippine Assembly, a legislative body based on extremely limited voting rights. On numerous occasions, the Filipino elites who dominated the Assembly used that forum to object to the visual representations of the Philippines that circulated around the world in publications like National Geographic. In 1914, the Assembly took a remarkable step and voted to outlaw “the taking, exhibiting, or possession of photographs of naked Filipinos” on the ground that these images “tended to make it appear that the Philippines were inhabited by people in the nude.” [4]

The legislators in Manila were hardly friends of the rural highland Filipinos on whose behalf they claimed to speak—in fact, they may have been embarrassed that images of “uncivilized tribes” stood in for the Philippines as a whole in the visual record upon which Americans gazed. Journalist Vicente Ilustre wrote in 1914 criticizing Worcester for showing images of “these unfortunates.” [5]

Filipinos’ efforts to control the camera’s power drew a rebuke from Dean Worcester. In testimony before Congress in 1914, Worcester told the Senate:

[w]e have twice had bills passed … intended to make it a criminal offense for any person to take a photograph of those fellows up in the hills. The Filipinos want to conceal the very fact of the existence of such people. There has been agitation in favor of the destruction of the whole series of Government negatives showing the customs of the non-Christian people, the conditions which we found among them and the conditions which prevail today.” [6]

The proposed bill never became a law. Through most of the colonial period, legislation required the approval of the Philippine Commission (on which Dean Worcester served) or the governor-general, and calls for modesty in rural photography were outvoted by an insistence on the value of the images for ethnographic research. The shape-shifting of visual anthropology—at once political surveillance, savage romance, and colonial fantasy, always cloaked under the gaze of science—allowed it to elude the attacks of critics.

Looking Back

The photographic encounters between Worcester and his sitters range from friendly and easygoing to violent and unwilling. But the collection is massive and among its images are striking views of men and women who lived through revolution, war, and colonialism at the turn of the century and looked back at the camera in ways that capture our attention today, reminding us that the photographic archive is never completely at the mercy of the storyteller. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Closing Up Shop

Dean Worcester never stopped taking photographs, but in the final years of his life he no longer took them in an official capacity. In 1913, President Woodrow Wilson and the Democrats took office and promised a new departure for America’s Philippine policy; longtime colonial officials—most of them known to be Republicans and devotees of former presidents Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft—found themselves out of jobs. Worcester offered his resignation in September 1913 and by the 1920s had moved to the province of Bukidnon in the southern Philippines, where he tried his hand as a ranch owner.

By the time Worcester left government service in 1913, the camera was ubiquitous in the Philippines. It was no longer the sole property of colonial officers. Photographic images were part of the day-to-day experience of American colonial officials, and they increasingly surrounded Filipinos as well. As a global consumer culture increasingly penetrated Southeast Asia, photo studios popped up along the streets of Manila’s fashionable shopping districts, and photographers soon set up shop in small towns throughout the colony. Filipinos increasingly took their own photographs, depicting their own lives and communities away from the gaze of colonial officials. In fact, there was decreasing interest in photographic accounts of the Philippines, and after Worcester’s departure, little support for ethnographic study of the colony. The Bureau of Non-Christian Tribes closed in the 1930s, and Worcester’s photo collection was donated to the Museum of Natural History in New York City, and then transferred to the University of Michigan Museum of Anthropology.

Meanwhile, viewed from a century’s distance, the photographs in the Dean Worcester Collection teach us invaluable lessons: foremost, they underline the need to consider the power relations in any visual encounter, but particularly in those interactions that take place on a visual terrain marked by inequalities of status, gender, and race. Second, these photographs remind us to pay attention to the circulation of such images. Even a century later, they must be handled with respect for the people and the cultures they depict.

But perhaps the final lesson is that these photographs teach no easy lessons. As viewers scrutinize these images, wondering what was going through the minds of Dean Worcester and other photographers, wondering how these images were collected and circulated, wondering what it was like to sit for such a photograph or to come across it later—we must tread carefully, forego the impulse of the snapshot and its easy legibility, and start to look in new and more egalitarian ways.

|

|

| |

|

|

|