|

| |

If the camera was an invaluable weapon in the military conquest of the Philippines after 1898, photography also helped Americans make sense of their new colonial subjects in Southeast Asia in the years after the war’s official end. During the early-20th century, both photography and American political power underwent rapid and dramatic change. Neither was entirely new; the rhetoric of “manifest destiny” had pushed American settlers across the Pacific in the 19th century, and photographs had been around for decades. But the years around 1898 brought a burst of political and visual innovation as the camera came to be a standard visual tool both in the United States and the Philippines. This unit tracks the relationship between photography, anthropological knowledge, and political power in the Philippines by exploring the photo collection of one American colonial official.

Dean Worcester organized, catalogued, and annotated his photo collection himself. This essay reproduces Worcester’s captions as a window into his visual imagination.

|

|

| |

The photographs in this unit, unless otherwise noted, are from the

Worcester Photographic Collection, courtesy of the

Museum of Anthropology, University of Michigan.

|

|

|

| |

DEAN WORCESTER'S WORLD

For most Americans in 1898, the Philippines was a new and distant place. The United States concluded a brief war with Spain in August 1898, and the terms of the Treaty of Paris, signed in December, granted the Philippines to the United States in exchange for a $20 million payment to the Spanish Empire. Americans avidly sought to learn about the “white man’s burden” that they had taken up across the Pacific. Representations of what British poet Rudyard Kipling called America’s “new-caught sullen peoples” circulated in the metropole, peddled with appealingly visual titles such as Fighting in the Philippines: Authentic and Original Photographs (1899) or Our Islands and Their People as Seen with Camera and Pencil (1899). One of the first books to reach American readers was The Philippine Islands and Their People, published in September 1898 by Dean C. Worcester, identified on the book’s title page as an Assistant Professor of Zoology at the University of Michigan.

|

|

|

| |

Dean Conant Worcester, seated front and center, captioned this photograph: “Our party and a group of Ilongote chiefs,” 1900.

Location: Dumabato, Isabela

[dw02d043] detail

|

|

| |

Indeed, Worcester’s initial interests in the Philippines were biological, not political. Born in rural Vermont in 1866, he first traveled to the Philippines in 1887 as a student member of a University of Michigan bird-watching expedition led by his professor, Joseph Beal Steere. He returned in 1890 for another expedition in the company of Frank L. Bourns, a fellow scientist and photographer. Not content to record the local bird life, the two men traveled to the most remote regions of the islands, meeting hunters and farmers, warriors and fishermen, all of them subjects for Worcester’s camera.

Dean Worcester’s rapid rise in 1898 from zoologist to colonial kingmaker was a mix of expertise, happenstance, gumption, and connection. He was, in part, in the right place at the right time: when the Spanish-American War began in April 1898, few Americans had ever even been to the Philippines, let alone had any expertise about the place, ornithological or otherwise. In the space of just a few weeks, Worcester turned his letters home into a published book—one of the first to reach American readers, and definitely the most lavishly illustrated.

One of Worcester’s readers may have been President William McKinley, who invited Worcester to meet with him at the White House in December 1898. McKinley appointed Worcester to the Philippine Commission, the first institution of civil government in the country, from 1899 to 1901. Worcester went on to serve as secretary of the interior of the Philippines from 1901 to 1913, and—with only a few interruptions for travel in the United States—would spend the rest of his life in the Philippines. But it was those 14 years of colonial service that mattered most for Worcester, for the U.S. colonial government, and for the ways that the state visualized the Philippine Islands and their people.

Dean Worcester loved cameras. He had begun taking photographs as a young man, and by the time he left for Manila on the Empress of Japan in January 1899, he was a capable photographer who entertained himself aboard ship by taking group shots and tinkering with his camera.

|

|

|

| |

Worcester included himself (seated far left) in this group photograph with “members of the first Philippine Commission and staff” while at sea in 1899.

Worcester’s caption: “Members of the first Philippine Commission

and staff on board the ‘Empress of Japan’,” 1899.

Location: Empress of Japan, Pacific Ocean

[dw59b003]

|

|

| |

Within a few years, Worcester had amassed considerable power in the colonial administration, incorporating into his portfolio as secretary of the interior responsibility for a wide range of undertakings: health, forestry, public lands, agriculture, weather, mining, government laboratories, and non-Christian tribes. As part of his official duties, Worcester regularly traveled through the 7,000 islands of the Philippine archipelago and met with some of the country’s 10 million inhabitants. On his investigations, he always brought along his own camera or hired a photographic assistant. Worcester praised Charles Martin, his favorite photographic assistant, for having “made a large series of valuable negatives which afford a permanent photographic record of conditions at present obtaining among many of the non-Christian tribes of the archipelago and of their manners and customs.” [1]

Ilustrados: Worcester Documents Manila

Worcester’s headquarters were in the colonial government buildings in Manila, where he interacted with a diverse, urbanized population, most of them Western in religion and dress, some of them close collaborators with the new American regime, and only a few of them captured by his camera. The so-called “ilustrados” (from the Spanish word for enlightened) included Spaniards who had traveled to Asia as part of the colonial government, as well as Spanish-speaking elites in the major cities, along with ethnic Chinese merchants and laborers.

|

|

|

| |

Most of the Filipinos Dean Worcester interacted with during his career as a colonial official were urban, Spanish-speaking elites such as those seen above. Worcester took relatively few photographs of these men and women known as “ilustrados” (from the Spanish word for enlightened).

Worcester’s caption: “Don Pedro Sanz, his Visayan wife,

his sons-in-law, daughters, and grandchildren,” 1899.

Location: Manila, Manila

[dw48B004] detail

|

|

| |

In addition to the non-Christian groups that fascinated Worcester, he also photographed groups he labeled as “Spaniards” and “Spanish-German Mestizos,” here six young women.

Worcester’s caption: “Group of six women; with the exception of

No. 1, all are Visayan-Spanish mestizas,” 1901.

Location: Dumaguete, Eastern Negros

[dw49A021]

|

|

| |

In the Philippines, Worcester encountered a substantial Chinese minority population. But he appears to have spent very little time photographing the ethnic Chinese or their neighborhoods.

Worcester’s caption:“A Chinaman carrying fruit on a pinga,” 1899.

Location: Manila, Manila

[dw57R006]

|

|

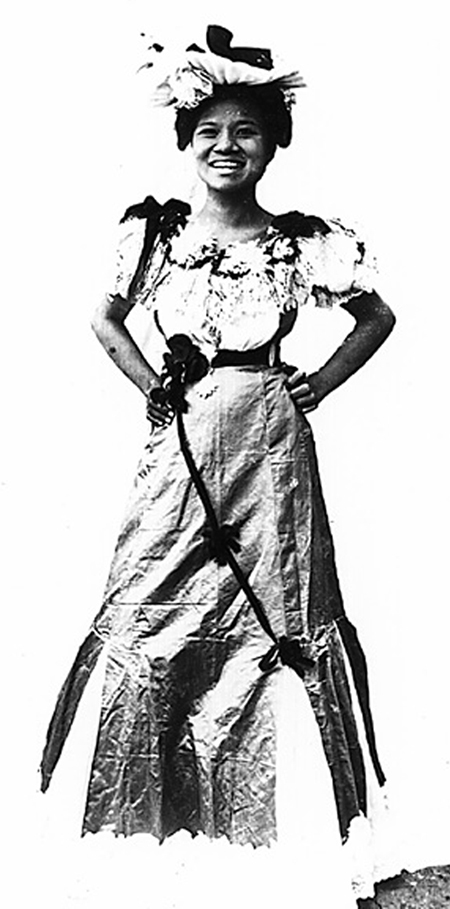

Images of urban, Westernized Filipinos—like this vivacious young actress from the northern Philippine province of Abra—were rare in Worcester’s collection, which focused on the rural and tribal Filipinos of the country’s more remote regions.

Worcester’s caption: “An Ilocano actress laughing. Full length front view,” 1905. Location: Bangued, Abra

[dw39b012] detail |

|

| |

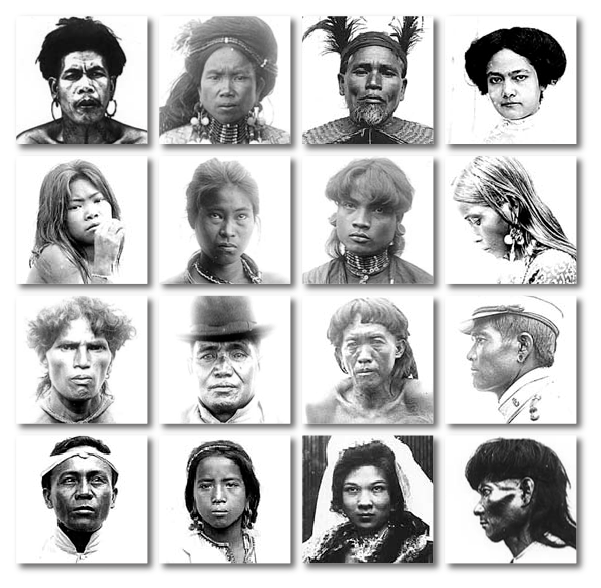

Taken as a whole, the Worcester Collection does not evenly represent the ethnic diversity and cultures of the Philippines in the early-20th century. By contrast, it clearly reflects Worcester’s preoccupation with classifying the “primitive” racial types that he encountered in the mountain highlands and distant islands. Despite his day-to-day interactions with urban Filipinos, Worcester took the overwhelming majority of his photographs in the most remote regions of the Philippines.

No one told Dean Worcester to collect these photographs, but the adventure of travel, the technical challenge and excitement of camera work, and the documentary evidence that it produced must have appealed to Worcester’s larger-than-life personality and outsized physical presence. With the authority he held as head of the Philippine Bureau of Science, Worcester set out to amass thousands of photographs of people and places in America’s new colony. The Bureau of Science, which Cameron Forbes, another American colonial official, described as “a great science library serving as a storehouse of knowledge not only for the Philippines, but for much of the East,” took its camera work seriously. As Forbes noted, “[i]f a photograph were needed, this bureau not only took it, but filed it away so that it might be available in years to come.” [2]

Worcester’s motives were simultaneously scholarly and political. “Now that the Philippine islands are definitely ours,” wrote anthropologist Daniel Brinton in 1899, “it behooves us to give them that scientific investigation which alone can afford a true guide to their proper management. … [A] thorough acquaintance with the diverse inhabitants of the archipelago should be sought by everyone interested in its development.” [3] Dean Worcester took up the challenge of documenting the diversity of the Philippines, with the goal of both understanding the Filipino people and learning how to govern them.

Worcester focused his attention on the most rural groups. “[T]here are probably no regions in the world,” he later explained, “where … there dwell so large a number of distinct peoples as are to be found in northern Luzon and in the interior of Mindanao.” [4] A catalogue of his collection arranged by ethnic group shows a preponderance of images taken among mountain-dwelling Igorots and Tingian Islanders, and relatively few images taken of urban Ilocanos and Tagalogs.Number of Photos by Social Group:

Bagobos (3)

Batanes Islanders (12)

Benguet Igorots (97)

Bontoc Igorots (60)

Bukidnon (17)

Ifugaos (53)

Ilocanos (27)

Ilongotes (13)

Kalingas (46)

Lepanto Igorots (26)

Mangyans (17)

Manobos (20)

Moros (26)

Negritos (49)

Pampangans (2)

Pangasinanes (7)

Spaniards (15)

Spanish/German Mestizos (10)

Tagalogs (23)

Tagbanuas (15)

Tinguianes (83)

Tirurayes (1)

Visayans (12)

Zamboangueños (1) Using Worcester’s photographs along with maps and documents, American officials began to chart the new colony’s ethnic landscape. But their scholarly confusion showed the impossibility of their undertaking; in 1900, Dean Worcester asserted that the population of the Philippines included three “races” and 84 “tribes,” while three years later the Philippine census counted 24 tribes—eight of them “civilized” and 16 of them “wild.” [5] The world that Dean Worcester mapped was at least partly a landscape that he himself had imagined.

|

|

|

| |

Map titled “Races and Tribes of the Philippines,” from Herbert W. Krieger, Peoples of the Philippines (1942). Dean Worcester’s efforts to map the ethnic landscape of the Philippines shaped American anthropological knowledge of the region for decades. In 1942, when the Smithsonian Institution published a series titled War Background Studies, Herbert W. Krieger drew this map based on Worcester’s earlier reports.

|

|

| |

In a memoir written at the end of his career, Worcester reflected on his time with the Bureau of Non-Christian Tribes.

At the outset we did not so much as know with certainty the names of the several wild and savage tribes. … As I was unable to obtain reliable information concerning them on which to base legislation for their control and uplifting, I proceeded to get such information for myself by visiting their territory, much of which was quite unexplored. [6]

The spirit of adventure and exploration that had brought the young man to the Philippines in the 1880s had become a technique of colonial governance. Worcester’s fascination with the rural Philippines reflected his official role as head of the Bureau of Non-Christian Tribes as well as the paternalism of empire and the romance of agrarian lifestyles that he saw disappearing before the progress of Western civilization. When comparing rural indigenous Philippine ethnic groups to urban Filipinos, Worcester noted that:[a]t present the pagan tribes consider themselves to be the ones who are better off, and I am bound to say I believe they are right. [7]

Just as important as what Worcester and other colonial photographers saw through their camera lenses is the question of how they looked through them in the first place. |

|

| |

|

|

|