|

| |

Between 1898 and 1902, the United States invaded, conquered, and colonized the Philippines. The Philippine-American War suppressed an indigenous movement for national independence, turned a former Spanish outpost into the centerpiece of a new American empire, and set the United States on a path of global engagement at the dawn of the 20th century.

Cameras were there from the beginning, as American soldiers, colonial officials, and journalists used photography as a tool of colonial conquest. But, just as the Americans found they could not completely control the Filipinos who were their new colonial subjects, they discovered that photographic images were not easily controlled either.

This unit uses the turn of the century’s explosion of photographic material—snapshots, stereoviews, illustrated books—to explore the relationship between photography and power in the colonial Philippines. Most of the images in this unit come from archival repositories such as the Library of Congress or university collections, as well as from illustrated books and albums published at the time.

“Photography & Power in the Colonial Philippines—1” depicts both the patriotic imagery of American engagement in a “civilizing mission” and the harsh imagery of uncivilized wartime conduct that provoked criticism among anti-imperialist activists in the United States and the Philippines. The unit also reveals how other visual materials such as illustrations and political cartoons opened a window on controversial areas that were frequently excluded from the photographic record in the United States.

Photographic images from the Philippines circulated widely in illustrated books. The “Sources & Credits” section contains links to more than two-dozen books available online in full-text formats.

|

|

|

| |

SNAPSHOTS

As American soldiers, politicians, and journalists entered the Philippines in the first days of the 20th century—or observed the war from across the Pacific—they used photographic images to come to terms with their new surroundings in Southeast Asia.

There was much to make sense of. The Philippines was, for most, an unfamiliar landscape, a destination determined for Americans by another war half the world away in the Caribbean. Political unrest in the 1890s in the Spanish colony of Cuba—including the February 1898 explosion of the U.S.S. Maine in Havana harbor under mysterious circumstances—prompted the United States to launch a war on Spain two months later. Begun in late April 1898, the war with Spain was over by August. Only 460 Americans died in battle or of wounds—although more than 5,000 died of disease in the field.

A decade after Kodak introduced the easily developed film roll in 1888, cameras were clicking all over the Philippines. American soldiers tucked photographs into the letters they sent home; other images were reproduced on postcards or stereographs for commercial distribution.

Ordinary soldiers took photographs to document their daily lives and the unfamiliar world around them. Their officers turned to the camera as a tool of surveillance and documentation that they believed would quell the Philippine revolution. Politicians hoped that images of uplift and progress would sell the war to a skeptical public, and plenty of journalists cooperated—knowing that illustrated books on the Philippines were sure sellers to an American public curious about its new far-flung empire.

|

|

|

| |

Original caption on stereograph: “‘Dearest Annie,—to-morrow we move on toward Santiago where we expect a hard battle,” ca. 1899. American soldiers tucked photographs into the letters they sent home; other images were reproduced on postcards or stereographs.

Source: Library of Congress [view]

[1899_LOC_3c11748u_dearestAnnie]

|

|

| |

Soon after the Spanish-American War ended, U.S. Secretary of State John Hay made passing reference to the conflict as “a splendid little war.” It was not splendid. It was not little. And it was not simply a war with Spain. The war in the Philippines was larger in scale and waged against a different enemy; in May 1898 U.S. sailors had been dispatched—under the orders of acting Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt—from Hong Kong to Manila.

In Manila, the Americans met and conquered a fragment of the Spanish navy, but they also encountered a mass national movement for Philippine independence that rejected the transfer of imperial power from Spain to the U.S.

|

|

|

| |

A print titled “Battle of Manila” depicts the battle at Manila Bay,

fought May 1, 1898. The USS Olympia (left foreground) and the U.S. Asiatic Squadron under the command of Rear Admiral George Dewey (portrayed in the left corner) engaged in a battle that destroyed Spain’s Pacific fleet during the Spanish-American War (1898).

Source: U.S. Naval History & Heritage Command Photograph [view]

U.S. Naval History & Heritage Command Photograph

[ph009_1899_NH91881-KN]

|

|

| |

Album caption: “Admiral Dewey's flagship ‘Olympia’ Manila Bay—1899”

Source: Museum of Anthropology, University of Michigan [view]

Courtesy of the Museum of Anthropology, University of Michigan

[ph220a_1899_phla815SID_UMich]

|

|

| |

Relations with the fledgling Philippine Republic and its leader Emilio Aguinaldo quickly deteriorated. By February 1899, the United States found itself engaged in a violent and protracted war that sent more than 100,000 soldiers across the Pacific and bitterly divided the American population at home.

|

|

| |

Original caption: “The Flag must ‘Stay Put.’ The American Filipinos and the native Filipinos will have to submit.”

This 1902 two-page graphic in the American magazine Puck depicted the U.S. conquest of the Philippines in a heroic light. On the left, prominent U.S. anti-imperialists (dismissed by the magazine as “American Filipinos”) protest American actions in the Philippines.

Puck 51 (June 4, 1902).

Source: Library of Congress [view]

[ph173_1902_4June_HOAR_lcpp_25641u_loc]

|

|

| |

The next four years of protracted guerrilla warfare devastated the Philippines. Scholars estimate that in a population of about 10 million people, at least 400,000 Filipinos died of war, disease, and starvation. By contrast, American fatalities numbered slightly over 4,000, three-quarters of whom died of disease.

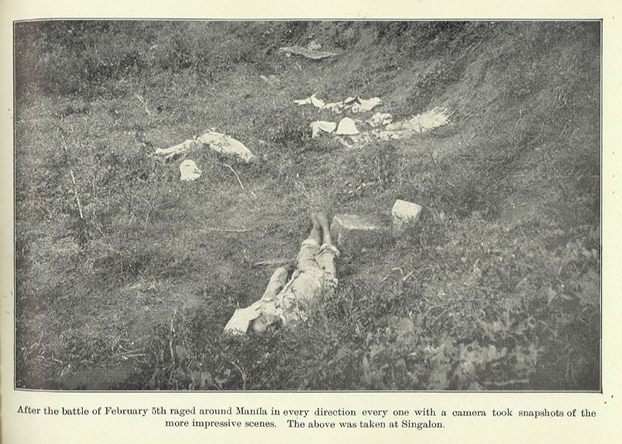

From the earliest days of the war, that destruction was captured by the camera and communicated to Americans at home. Soon after the first battle of the war, one American observer noted that “after the battle of February 5th raged around Manila in every direction every one with a camera took snapshots of the more impressive scenes.” It should come as no surprise that Americans made sense of this war-torn landscape with “snapshots”: the word, after all, had by 1898 already migrated from its original meaning denoting a sharpshooter’s rifle work to a description of the rapid-fire click of the photographic shutter.

|

|

|

Photo and caption from an 1899 album published in Chicago

and titled Fighting in the Philippines: Authentic Original Photographs (F. Tennyson Neely Company, 1899).

Caption published with the photograph: “After the battle of February 5th raged around Manila in every direction every one with a camera took snapshots of the more impressive scenes. The above was taken at Singalon.”

The majority of photos of this nature focused on enemy corpses rather than American fatalities.

[View the album in full on Archive.org]

[ph037_1899_PIPH002] |

|