| |

A DESTRUCTIVE CONCLUSION

The Summer Palace of the Qing Emperors & its Destruction

The wanton looting of the Yuanmingyuan by French and British forces, and its October 1860 destruction by fire, were decried by many, including the renowned French novelist Victor Hugo, who framed it in terms of civilization and barbarism, terms commonly used in the West to justify overseas wars.This edifice, as enormous as a city, had been built by the centuries, for whom? For the peoples. For the work of time belongs to man. Artists, poets and philosophers knew the Summer Palace; Voltaire talks of it. People spoke of the Parthenon in Greece, the pyramids in Egypt, the Coliseum in Rome, Notre-Dame in Paris, the Summer Palace in the Orient. If people did not see it they imagined it. It was a kind of tremendous unknown masterpiece, glimpsed from the distance in a kind of twilight, like a silhouette of the civilization of Asia on the horizon of the civilization of Europe. This wonder has disappeared. One day two bandits entered the Summer Palace. One plundered, the other burned. … We Europeans are the civilized ones, and for us the Chinese are the barbarians. This is what civilization has done to barbarism. Before history, one of the two bandits will be called France; the other will be called England. (excerpt from letter, Victor Hugo, November 25, 1861)

|

|

|

| |

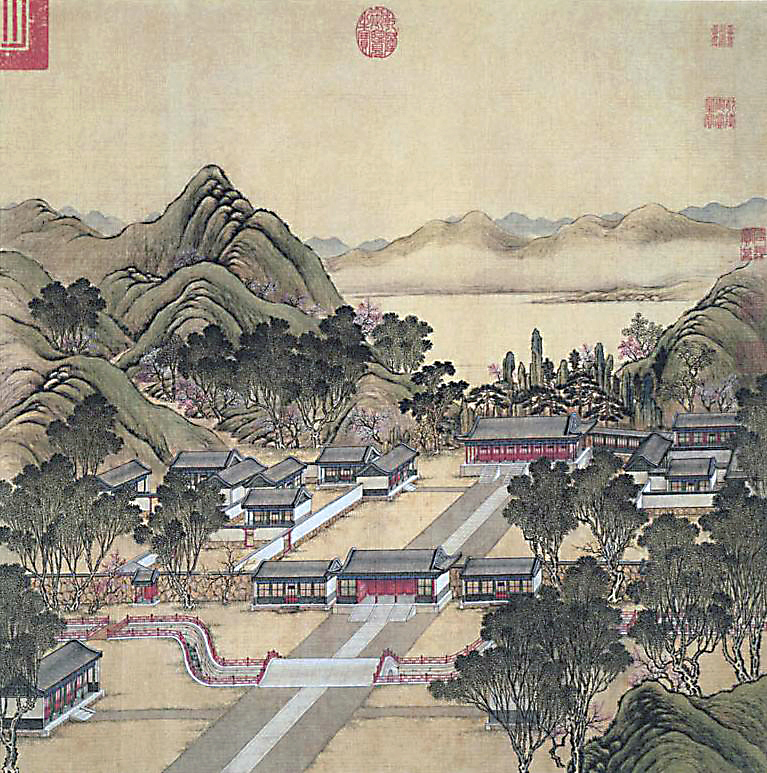

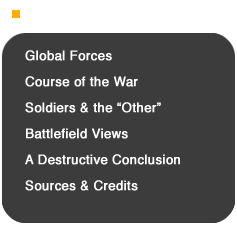

“The Main Audience Hall,” where the emperor received officials and guests, at the Yuanmingyuan (Garden of Perfect Brightness): first in a set of 40 paintings commissioned by the Qianlong emperor in 1744. Two court artists, Shen Yuan and Tangdai (a Manchu), and a calligrapher, Wang Youdun, undertook this work. In 1860, the album was seized by French troops, taken back to France, and held at the Bibliothèque Nationale, where it remains to this day.

MIT Visualizing Cultures

[ymy1001_Zhengda_detail-31]

|

|

| |

Yuanmingyuan (the Summer Palace) was an 18th-century complex of pavilions and gardens located about 9.3 kilometers (5.8 miles) from the northwest gate (Xizhimen) of Beijing’s city wall.

MIT Visualizing Cultures

[ymy_map2]

|

|

| |

Translated from French:

“China. Taking of the summer residence of the Emperor of China—The Allies commanded by General Montauban, attack the Yuengminyuen Garrison (a town 2 leagues from Beijing) put the Chinese on the run and seize the Palace

(September 5, 1860)”

Lithograph print by L. Scherer, undated

BibliothŤque Nationale de France

[1860_Chine_prise_residence]

|

|

| |

While Allied troops looted the Yuanmingyuan (October 7–9, 1860), forces under Lord Elgin camped outside of Beijing, waiting for the Qing to accept the 1858 Treaty of

Tianjin. The treaty had, among its provisions, opened eleven new treaty ports, three of them deep in the interior, and allowed foreign ships in the Yangzi river. Officials would have to welcome and protect foreign missionaries,

diplomats, and merchants. Taxes on foreign imports, including legalized opium, went to pay an indemnity for the cost of the war.

Official communications were to be written in

English, and the character yi, or “barbarian,” was forbidden in reference to the British.

The emperor had refused to ratify the treaty or recognize any of its terms: hostilities ensued over its enforcement. By the 1860 siege of Beijing he had fled, leaving Prince Gong in charge. Elgin and Gong agreed to a truce on October 11.

On October 15, Elgin was told by his colleagues that China must sign a new treaty before winter. Allied equipment shortages, and fears that the French would abruptly quit the alliance, threatened the expedition. He also learned of the deaths of European prisoners, and wished to punish the emperor personally. An attack on the Forbidden City, however, could violate the truce and frighten off the Qing's negotiators. “… The destruction of Yuen-ming-yuen was the least objectionable of the several courses open to me,” Elgin later wrote (Letters and Journals of James, Eighth Earl of Elgin. London, 1872, p. 366).

On October 18 and 19, General Sir Hope Grant's men, including engineers skilled in demolition, burned most of the Yuanmingyuan to the

ground. In the words of one British observer, By the evening of the 19th October, the

summer palace had ceased to exist…some blackened gables and piles of burnt

timbers alone indicating where the royal palaces had stood. …When we first entered

the gardens they reminded one of those magic grounds described in fairy tales; we

marched from them upon the 19th October, leaving them a dreary waste of ruined

nothings. (G. J. Wolseley. Narrative of the War with China in 1860,

London, 1862, p. 280) He thought that this “Gothlike act of barbarism” would give an

“unmistakable reality to our work of vengeance,” impressing the Qing court with

British power (Wolseley, cited in Hevia, pp. 107, 109). Prince Gong was forced to accept

the treaty, pay an even larger indemnity, and give up the Kowloon

peninsula to Hong Kong.

Photographic Record

Beato took rare photographs of the Yuanmingyuan prior to its destruction. In “Romanticizing the Uncanny,” Maureen Warren notes that there is some ambiguity to the photographs' labels:

In October 1860, Felice Beato made 32 photographs of Beijing and the surrounding area, six of which are labeled “Yuan Ming Yuen.” However, at least four of them depict the Wanshou Shan (Hill of Imperial Longevity), a nearby imperial garden that was also referred to as the Yuanmingyuan in the nineteenth century. … Thiriez [Barbarian Lens, 9]

notes that perhaps the clock tower and airy pavilion … might be in the

Yuanmingyuan proper and speculates that Beato arrived when they

were destroyed. (Warren, pp. 233-250)

|

|

|

| |

Imperial Summer Palace, before the burning, Yuen-Ming-Yuen, Peking. Photograph by Felice Beato & Henry Hering (British, 1814-1893), between October 6–18, 1860

J. Paul Getty Museum

[Beato_10-06-a-before-burn]

|

|

| |

Though his memoir justified the burning of the Yuanmingyuan, Loch also expressed regret and resignation. He described the subsequent arrangements for the treaty signing:

During the whole of Friday the 19th, Yuan-Ming-Yuen was still burning;

the clouds of smoke, driven by the wind, hung like a vast black pall

over Peking. On the morning of Saturday the 20th, Lord Elgin received

Prince Kung’s absolute submission to all the demands of the Allies, and

the Prince requested that an early day should be named for the signature of the Convention and exchange of the Ratifications of the Treaty

of Tien-tsin. (Loch, Personal Narrative of Occurrences During Lord Elgin's Second Embassy to China, 1860. p. 4)

| |

|

| |

“The earliest known photographs of the ruins of the European section of the Yuanmingyuan were taken by Ernst Ohlmer in 1873, just 13 years after the looting and destruction of the site. 12 of the original glass negatives were collected for an exhibition at Beijing's China Millennium Monument in 2011. This depicts the north side of the Xieqiqu, one of the main palaces.” (Lillian M. Li, “The Garden of Perfect Brightness lll,” MIT Visualizing Cultures) MIT Visualizing Cultures

[1873_ohlmer_EuPav_ChMM]

|

|

| |

Legacies of the War, Forecasts of China's Fate

The burning of the Yuanmingyuan was designed as a deliberate punishment by the

forces of “civilization” of a backward people who refused to succumb to British power.

Lord Elgin called it a “solemn act of retribution” in revenge for Chinese treatment of

Western captives. As soldiers exulted in carrying off precious furniture, porcelain, and

silks to their regimental halls, these “imperial lessons” taught the Chinese that

they were powerless to stand up to British demands for free trade, spheres of

influence, and religious penetration of Chinese society. Civilization, in Western eyes,

entitled the victors to loot, humiliate, and inflict atrocities on others who would not

bow to imperialist demands.

The treaty ending the war not only pried open more of China’s ports, but also opened

the empire to missionary activity. France gained access to the empire’s interior for Catholic missionaries to proselytize:

this generated more

hostility in the countryside than any other intrusion. Anti-foreign mobilization beyond the court’s control flared

up soon after the second treaty was signed, and increased through the end

of the dynasty. Attacks on Christian missionaries and their followers would be part of all the succeeding confrontations of China and the West.

Other rising powers took notice. Russia, without paying the cost of an alliance, gained a

large amount of territory in Siberia and Manchuria. The United States, engaged in pressuring Japan to open its ports after Commodore Perry’s expedition in 1854, stood by as

a neutral power, but gained all the trading benefits achieved by the other Western powers. Japanese activists, seeing China’s fate, determined on a rapid, violent response to

foreign imperial pressure, ultimately leading to the overthrow of the shogunate in 1868.

Karl Marx (1818-1883) wrote a series of articles on the second Opium War as a correspondent for the New York Daily Tribune. His main sources were the London newspapers

and the accounts of Parliamentary debate over the war. Like Cobden, he rejected in scathing invective the

pretexts offered by the British for the war. Marx stated that the

real cause was Bowring’s “monomania” about forcing entry into Canton, and the expansion of British trade. He denounced the “atrocities” inflicted on China by the bombardment of Canton, the opium trade, the coolie trade, and the “bullying spirit often exercised against the timid nature of the Chinese.” He predicted that: …the smothered

fires of hatred kindled against the English during the opium war have burst into a flame

of animosity which no tenders of peace and friendship will be very likely to quench. (Karl Marx: Daily Tribune, April 10, 1857) He

argued that the masses of Chinese in the south had now begun a

“fanatical … struggle”

against the foreigners, even poisoning the bread of the English in Hong Kong. We had

better recognize that this is a … popular war for the maintenance of Chinese nationality,

with all its overbearing prejudice, stupidity, learned ignorance and pedantic barbarism if

you like, but yet a popular war. (Marx: Daily Tribune, June 5, 1857) He also predicted: …the death-hour of Old China

is rapidly drawing nigh…. Before many years pass away we shall have to witness the

death struggles of the oldest empire in the world, and the opening day of a new era for

all Asia. (Marx: Daily Tribune, April 10, 1857)

Conclusion

The second Opium War, while brief in duration, set the basic course of China's modern history for the rest of the century. The war unleashed the full force of Western imperialism against the weakening Qing empire. China became a true semi-colonial state, threatened by internal rebellion and foreign encroachment at the same time. The core structures of Chinese civilization—its palaces, its cities, and its borders—had been violated by foreign invaders.

Large audiences in the West, informed by the new technologies of photography and illustrated mass media, celebrated this demonstration of imperial victory over a backward Oriental people. The hapless Qing court, like the masses of ordinary Chinese, seemed to be mere disorderly rebels, or victims of irresistible force. Yet the Qing empire survived, and in the 1860s to 1880s launched an impressive campaign to strengthen its economic and military forces: removing the foreign presence from China so that it could “stand up” as an independent nation would become the primary goal of nationalist movements for nearly a hundred years.

Marx certainly exaggerated the degree of popular mobilization against the foreigners during the war, and the Qing dynasty lasted much longer than he—and most other observers—expected. However, he captured an important element which many others missed: the arousal of masses of ordinary Chinese against foreign invasion. This led to major rebellions like the Boxer Uprising, and then full-fledged Chinese nationalism: the dynasty would be overthrown in the early-20th century, and the People's Republic established in 1949.

| |

|

| |

Scroll left or right to view a panorama by Felice Beato.

Scroll left or right to view a panorama by Felice Beato.

August

10th, 1860”

Felice Beato, photograph taken in China

during the second

Opium War,

August 10, 1860

J. Paul Getty Museum

[Beato_08-10_Tangkoo-Fort]

View in the Image Gallery

|

|

|