| |

At present the nature or our commerce with the Chinese is such that we can pay for our purchases only partly in goods, the rest we must pay in opium and in silver. (Lord Palmerston, cited in J.Y. Wong, Deadly Dreams: Opium, Imperialism, and the Arrow War (1856–1860) in China, Cambridge University Press, 1998, p. 211)

On October 8, 1856, Chinese port officials in Canton harbor arrested crew members of the Arrow, a small boat which claimed to be a British ship, on suspicion of piracy. British representatives in Canton and Hong Kong claimed that this action insulted the British flag, and used the incident as a pretext to launch a second major war against China. Fourteen years after the signing of the 1842 Treaty of Nanjing, the British—this time with French allies—invaded China again and proceeded to inflict another severe defeat on the weakened Qing empire.

Many of Britain’s goals were the same as in the previous war: to force China to remove barriers to trade in British exports, especially opium, and to gain direct contact with Chinese officials to promote further trading relations. But the global position of both Britain and China had shifted substantially. With the industrial revolution well underway, Britain had become the preeminent global economic power, extending its tentacles everywhere in search of raw materials for industry and outlets for its manufactures.

British manufacturing needed raw materials from all over the world, and markets to sell its massive output of industrial goods. But the British faced resistance from other imperial powers and from their colonies. They successfully pushed back Russian expansion in the Black Sea in the Crimean War, but they faced a major uprising by Indian troops in 1857. British leaders knew that further expansion of trade was the only way to maintain their position as the world’s dominant power.

|

|

|

| |

The Crystal Palace exhibition of 1851 displayed to a global audience the new technologies and manufactures in which Britain led the world..

“Crystal Palace, View from the Water Temple”

Photograph by Philip Henry Delamotte, 1854

Smithsonian Libraries

[Crystal_Palace_gen_view]

|

|

| |

China, by contrast, had fallen in economic strength and political cohesion, challenged by major rebellions in its most productive areas. The Taiping rebellion (1853–1864), striking much of the most productive regions of south China, endangered the entire security of the empire from within. The civil war engulfed most of China and—with 20 to 30 million war dead—was among the bloodiest in history.

Facing outward, the Qing court adhered to the provisions of the Treaty of Nanjing, but it strongly resisted any treaty revision pushed by the British. The British, taking advantage of a minor conflict to launch a preconceived strategic plan for war, demonstrated their vast naval superiority: bombarding, invading, and looting Chinese cities. The outcome of the war, including the burning and looting of the Yuanmingyuan—the Summer Palace of the Qing emperors—and the imposition of heavy indemnities was much more humiliating than that of the first opium war.

|

|

| |

The name of the war itself indicates different perspectives on it, and contradictory interpretations of its causes and significance have proliferated ever since it took place. The British usually called it the Arrow War, after the name of the British-registered ship whose detention by the Chinese provided the pretext for the war. The French, naturally enough, called it the Anglo-French War. But the term “Second Opium War,” first used by Karl Marx, best captures its underlying causes and its continuity with the first Opium War. This war too centered on opium—the major trade good supporting British rule in India. The treaty ending the first Opium War did not mention opium, but the treaties ending the second Opium War in 1860 specifically legalized the opium trade in China.

The war’s impact, however, led to many fateful results beyond the expansion of the opium trade. Continued foreign encroachment from all sides, combined with internal disorder, began the process leading to the fall of the Qing dynasty in 1911. The Western powers aspired to transform not only China’s trade, but its government and culture—more radically than previous foreign conquerors had done. Christianity, gunboat diplomacy, condescension, Orientalism, and racism flourished in the wake of the war much more than in the first part of the century.

The British View

In the visual imagery and illustrated press, we can see themes of a war between “civilization” and “barbarism” that would dominate Western attitudes through the end of the century.

The war coincided with a rapid expansion of the popular press, in print and illustrated form. The repeal of the British stamp tax in 1855 made newspapers much cheaper, expanding their readership. Although there was no universal education in England, literacy increased as the number of salaried non-industrial workers rose. These papers spread news of major foreign events to a larger reading public, including middle and lower classes. Telegraph lines now extended as far as Trieste, providing instant communication of diplomatic events in Europe.

News from the far East took longer to arrive, but steamers reduced travel time from Asia to several months. The delay in communications between London and Hong Kong allowed British representatives to act on their own, but once news arrived in England, popular opinion reacted immediately to unfolding events.

Party alliances, stirred up by the new political press, mobilized the electorate to debate domestic and foreign affairs with intense interest. The Reform Act of 1832 had enlarged the electorate to 650,000, one-fifth of the male population of England. It was still a small percentage of the nation, but it made England a true democracy, where voters put public pressure on their representatives to follow their opinions.

|

|

|

The liberal leader, Lord Palmerston (foreign secretary during most of the time between 1830 and 1851, and prime minister from 1855 to 1865), advocated an aggressive policy of upholding British interests by force wherever they were challenged. He faced opposition, however, from those who feared the expense of military conflict, and liberal Victorians bothered by their consciences over the opium trade.

The Parliamentary election of 1857—called the “Chinese election” because it focused on the war in China—pitted Palmerstonís vigorous advocacy of expansion in defense of economic interests against critics of the opium trade and British adventurism.

Right: Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston.

Caricature portrait by Carlo Pellegrini, ca. 1860

National Portrait Gallery, London

[Palmerston-by-Pellegrini.jpg]

In the debate over the China war, Palmerston denounced his critics for proposing to “abandon a large community of British subjects at the extreme end of the globe to a set of barbarians—a set of kidnapping, murdering, poisoning barbarians.” (Lawrence James, The Rise and Fall of the British Empire, St. Martin’s Press, New York, 1995, p. 177.)

In this rhetoric, the sentiment of “jingoism”—advocacy of imperial domination at any cost, and the demonization of Asian adversaries as “barbarians,”—made a strong appearance, typical of Palmerston’s style.

Visual imagery in the press supported these stereotypes. Imagery and rhetoric propagated the concept of Chinese officials as monsters who failed to follow decent rules of civilized humanity, while erasing or forgiving British atrocities against ordinary Chinese. Contempt for Chinese culture turned to ridicule as China’s military weakness was exposed. Missionaries, for their part, aimed to remove the “backward” customs of the Chinese people in order to lift them up to the “civilized” values of Christianity.

|

|

|

| |

The Search for a Profitable Opium Trade

After the Treaty of Nanjing, the British expected great profits from the China trade, but they were disappointed. Furthermore, opium had become even more necessary to the global trade connections of the empire. Exports of woolen and cotton goods rose over the next 20 years, but not nearly as fast as imports of tea and silk. The trade gap widened to 8 million pounds sterling by 1860.

|

|

| |

“Opium Smoking in China—From Drawing by a Native Artist,” two-page spread in The Illustrated London News, December 18, 1858 (p. 575)

MIT Visualizing Cultures

[co2_ILN_1858_1218_575_crop]

|

|

| |

Opium, known under the name of laudanum as the “poor child’s nurse,” still had a market in England but the China market was much larger. Even though the 1842 treaty itself did not legalize the opium trade, opium exports from India grew. The East India Company administration itself depended on revenue from opium exports, which paid up to two-and-one-half times the interest costs of the Indian administration’s debt.

British Pressure on Canton

The city of Canton, the first to be opened to Western trade in the late-17th century, fascinated British merchants, who were confined to a small area outside the city walls. On the local level, the British found themselves blocked in efforts to enter the city of Canton. Foreigners could reside in the treaty ports, but Chinese officials restricted the foreign settlements to the port area outside the city walls. They knew of vigorous trade going on within the city’s narrow streets, but they had no access to it. At the same time, just as in India, they perpetuated the classic images of the Orient as a site of confusion, dirt, drug addiction, and potential rebellion. This account of Hog Lane, a small street on the edge of the city, reveals their knowledge and prejudice:

… The foolish notion of fatalism which prevails among the people makes them singularly careless as regards fire, although the conflagration in 1822 went far to destroy the whole city. Hog-lane … is more narrow and filthy than anything of the kind in an European town; it is lined with miserable hovels, occupied by abandoned Chinese, who supply drugged spirits to the poor ignorant sailors; and when the wretched men have been rendered nearly insensible by their poisonous liquors, they are frequently set upon by their wily seducers, and robbed as well as beaten… (The Illustrated London News, March 18, 1843, p. 182) |

|

| |

|

|

| |

“East Street from the Treasury, Canton,”

photograph by Felice Beato (with Henry Hering), April 1860

J. Paul Getty Museum

[Beato_04-01-a-east-st]

|

|

| |

The great hostility of the Cantonese to a foreign presence in their city, provoked by the desecration of their tombs at Sanyuanli in 1842, meant that allowing foreigners into the city would instigate a riot. Yet John Bowring, the British plenipotentiary in Hong Kong—supported by Harry Parkes, the consul at Canton—became convinced that the British must enter the city. After repeated requests, the emperor promised to allow access to Canton in 1849, but local officials in Canton, fearing the upheaval it would cause, forged an edict rejecting it.

Ye Mingchen (1807-1859), governor of Guangdong province, was promoted to governor-general of Liangguang (the two provinces of Guangdong and Guangxi), and imperial commissioner after 1852 for his success in keeping the British out of Canton. He was, however, caught between the determined foreign pressure and the strong resistance of the local population to a foreign presence.

The Qing state also faced major challenges to its authority from rebellions in the 1850s: the largest was the Taiping rebellion. The Taiping originated as a sect of Christian believers who raised a large army in southwest China in the 1850s, and marched down the Yangzi river, capturing Nanjing in 1853. In Canton, also, Taiping supporters and other rebels known as the Red Turbans seriously threatened local authority. Ye Mingchen effectively organized local military forces to drive out the rebels. Although some Qing officials blamed Christian missionaries for inciting the rebellion, they were understandably far more concerned about the dangers of widespread rebellion than about free access of foreigners to the interior of China.

|

|

|

| |

“Portrait of Governor-General Yeh”

Chinese artist studio, Canton, ca. 1856

Wikipedia Commons

[Yeh_Canton-artist_c1856_wp]

|

|

| |

Seizing the Arrow

Faced with the failure of the China trade to meet his expectations, Lord Palmerston concluded that only radical revision of the Treaty of Nanjing could promote imperial British interests. He demanded free access of merchants to the Chinese interior, unlimited rights of navigation along the Yangzi river, prevention of transit duties on foreign merchandise, and the legalization of the opium trade. He openly advocated the use of force to make the Chinese concede. All he needed was a pretext.

On October 8, 1856, officials in Canton arrested the crew of a small Chinese boat named the Arrow, which claimed that it had registered in Hong Kong and had the right to fly the British flag. The boat had no papers and was clearly engaged in illegal trade. The British acting consul, Harry Parkes, claiming that the Chinese had insulted the British flag, demanded that Commissioner Ye surrender the boat and its men. Ye gave up the men, but after insisting on the right to investigate the ship’s crew for piracy, Parkes and Bowring bombarded Canton, forcing entry into the city. This provoked strenuous debate in China and England.

|

|

|

|

|

| |

“The Attack on the Barrier Forts Near Canton, China, by the American Squadron, Commander James Armstrong, Nov 21st 1856—Consisting of the US Sloops of War Portsmouth and Levant with the Officers and Crew of the Steam Frigate San Jacinto — Flag Ship. The landing parties were commanded by Captain Foote of the Portsmouth, Capt Bell of the San Jacinto, and Cap. Smith of the Levant.”

This image depicts a later American attack on Canton, not the original British bombardment of the city, but the landscape and style of ships are very similar. Note that the image depicts Canton as a sparsely populated countryside, and not as a huge city that contained millions of people. The pastoral imagery erases the real damage inflicted on the city by the bombardment.

Lithograph by Poinsett, A and Buffords, J H, 1856

National Maritime Museum

[1856_Canton-attack_nmm ]

|

|

| |

In England, Palmerston and the China merchants vigorously advocated a war against the “barbarian” Chinese. They denounced Commissioner Ye as a “monster” inflicting cruel punishments on foreigners and Chinese alike. (By contrast, Ye’s best modern biographer, J.Y. Wong, calls him a “pragmatic statesman, ingenious strategist, and a resourceful financier.") The British press, calling him “obstinate and bloodthirsty,” spread this demonic view of Ye to the public and to the leading politicians in Britain:

The present Governor-General of the two Kwang rejoices in the somewhat peaceable-sounding name of “Yeh.” His predecessor, Seu, had been unfortunate against the rebels in the years 1854-5, and was, therefore, superseded by the above-named Viceroy, who, if I am not wrongly informed, is a native of one of the southern provinces and undoubtedly a man of great abilities; obstinate and blood-thirsty, however, he certainly is to a degree. He was completely successful in beating off the rebel force that threatened the city about the time of his succession to power, and during the last eighteen months has been indulging his desire for vengeance on account of the members of his own family slain by the rebels, by sacrificing whole hecatombs of the suspected people who fell into his hands, in the execution ground of Canton.

This bloodthirsty propensity of his has at last, however, led him into a difficulty he could hardly have anticipated, or perhaps his successes against the rebels had somewhat dimmed his memory with respect to the events of 1840-41; at any rate his conduct requires some such explanation.

The Chinese authorities have issued proclamations calling on all good citizens to resist our “un-provoked” attack, stating as a reason that we have been defeated by Russia in our late war, and have now come to squeeze the people of China, in order to defray our expenses. Has Russia any hand in this matter? (“The War with China,” The Illustrated London News, January 17, 1857, pp. 38-39)

England’s War Debate

Others in England, however, inspired by a Victorian moral conscience, questioned the validity of a war that violated international law, and expanded a small incident into a major war for British power and trade, opium included.

|

|

|

|

Richard Cobden (1804-1865), a member of Parliament and prolific writer on trade issues, defended the right of the British to expand their global trade, but strongly criticized the coercive methods used by Palmerston and Bowring against China. In a speech in the House of Commons on February 26, 1857, he argued that the British had no legal right to attack China, that the military action was rash and damaging, and that the British should coordinate their actions diplomatically with the U.S. and France.

left: Richard Cobden, 1865 (detail)

photographed by Mathew Brady

Wikipedia

[1865_Cobden-by-Brady_WP]

| |

| |

Parliament approved Cobden’s motion of censure, forcing Palmerston to dissolve Parliament and call a new election. Those who rejected the warmongers were accused of being sympathetic to China due to private commercial interests. Punch magazine satirized the former Prime Minister Lord Derby and Richard Cobden—who criticized Palmerston’s war in Parliament—as sycophantic supporters of China, only interested in promoting the tea trade (“Bo-hea” and “Pee-koe” in the image below refer to the names of the two most popular varieties of Chinese tea). |

|

| |

“The Great Chinese Warriors Dah-Bee and Cob-Den,” Punch, March 7, 1857

The “Warriors” say the words “Boh! Hea!” and “Pee! Koe!” referring to the two most popular varieties of Chinese tea.

Yale University Library

[punch_1857-03-07-Dah-Bee]

|

|

| |

Cobden’s speech promoted a very different image of China and of international relations from Palmerston’s. In Cobden’s view, China deserved to be treated as a nation under law equal to the Americans, French, and Russians. Far from the monster depicted by Palmerston, Ye Mingchen was a reasonable, experienced official, trying to settle the conflict peacefully. China, as an ancient civilization with a culture older than—and comparable to—the Roman empire, deserved respect. War would not promote British trade interests, only damage commerce and provoke Chinese resentment.

Must it not be admitted—as was said by Lord Derby…that “on the one side [Chinese] there were courtesy, forbearance, and temper, while on the other [British] there were arrogance and presumption?… all the communications on the part of the Chinese authorities manifest a forbearance, a temper, and a desire to conciliate, which should put to the blush any man who asserts that they intended to insult the British representatives.”

Speaking for the people of Canton, he had them say, ”you are insisting on official receptions within the city. This is doubtless with a view to amicable relations; but, when your only proceeding is to open a fire upon us which destroys the people… the sons, brothers, and kindred of the people, whom you have burned out and killed, will be ready to lay down their lives to be avenged on your countrymen, nor will the authorities be able to prevent them.” (Richard Cobden, speech “on the the seizure of the Arrow by Chinese authorities and the subsequent shelling of Canton by British forces which led to the 'Second Opium War.' Given to the House of Commons, 26 February 1857.”)

Depictions of Ye in the popular press, however, supported the “savage monster” view of the jingoists. Palmerston dissolved Parliament, and won victory in the “Chinese election” of March 1857, taking advantage of jingoist press coverage and openly racist anti-Chinese rhetoric. He had gained support from the French for a joint expedition against China, but the Russians and Americans rejected his proposals. Although Ye offered negotiations, the allied forces bombarded Canton again, taking Ye prisoner in January 1858. Ye, after staying 48 days on the British warship HMS Inflexible, was brought to Calcutta and confined in Fort William. His capture was a sensational event widely reported by the British media. He died of an illness in prison in 1859.

|

|

|

|

|

| |

“Capture of Yeh-Ming-Chen by the British army, in 1858”

Wikimedia Commons

[1858_Canton_capture_Yeh]

|

|

| |

Keeping Russia out of Asia

Beside the trade deficit with China, British imperial policymakers mainly worried about Russian expansion. Russia’s efforts to move against the Ottoman empire led to the Crimean War of 1853 to 1856, in which Russia was defeated by an alliance that included Britain. But Russia continued to consolidate control over Siberia, as it promoted its trade with China through the border town of Kiakhta.

The British—seeking control of Chinese trade in the south—feared Russian domination over trade on China’s northern border. The high costs of the Crimean War and the fear of further Russian expansion to the east made the British more conscious of the China market’s value. Expanding trade with China by getting the Chinese to buy more British manufactured goods could support British imperial projects throughout Asia, both in India and against Russia. Russia, for its part, concluded that it needed to occupy more territory in eastern Siberia to protect its trading interests.

Russia, like England, imported large quantities of tea from China, and hoped to expand trade from its existing exports, like fur, into other industrial goods. British newspapers published reports like this one, clearly recognizing the growing rivalry between the two countries over access to trade and territory in China:

The Russians appear to be very much alarmed at our proceeding in China. A letter from St. Petersburg of the 8th, in the Journal des Débats, says: “The news of the attack on Canton by the English fleet has produced a considerable sensation here. It appears certain that dépôts of goods belonging to Russian merchants have been burnt, and that their loss of property has been considerable. This act, which is perfectly unjustifiable, and for which no serious motive can be assigned, is regarded here as the prelude to the conquest which the English propose to themselves to make of the Island of Chusan.”

(“The War with China,” The Illustrated London News, January 1857, p. 86) In 1860, taking advantage of China’s defeat, a Russian military expedition founded Russia’s first major city on the Pacific coast, Vladivostok.

|

|

| |

Chinese Sea Power

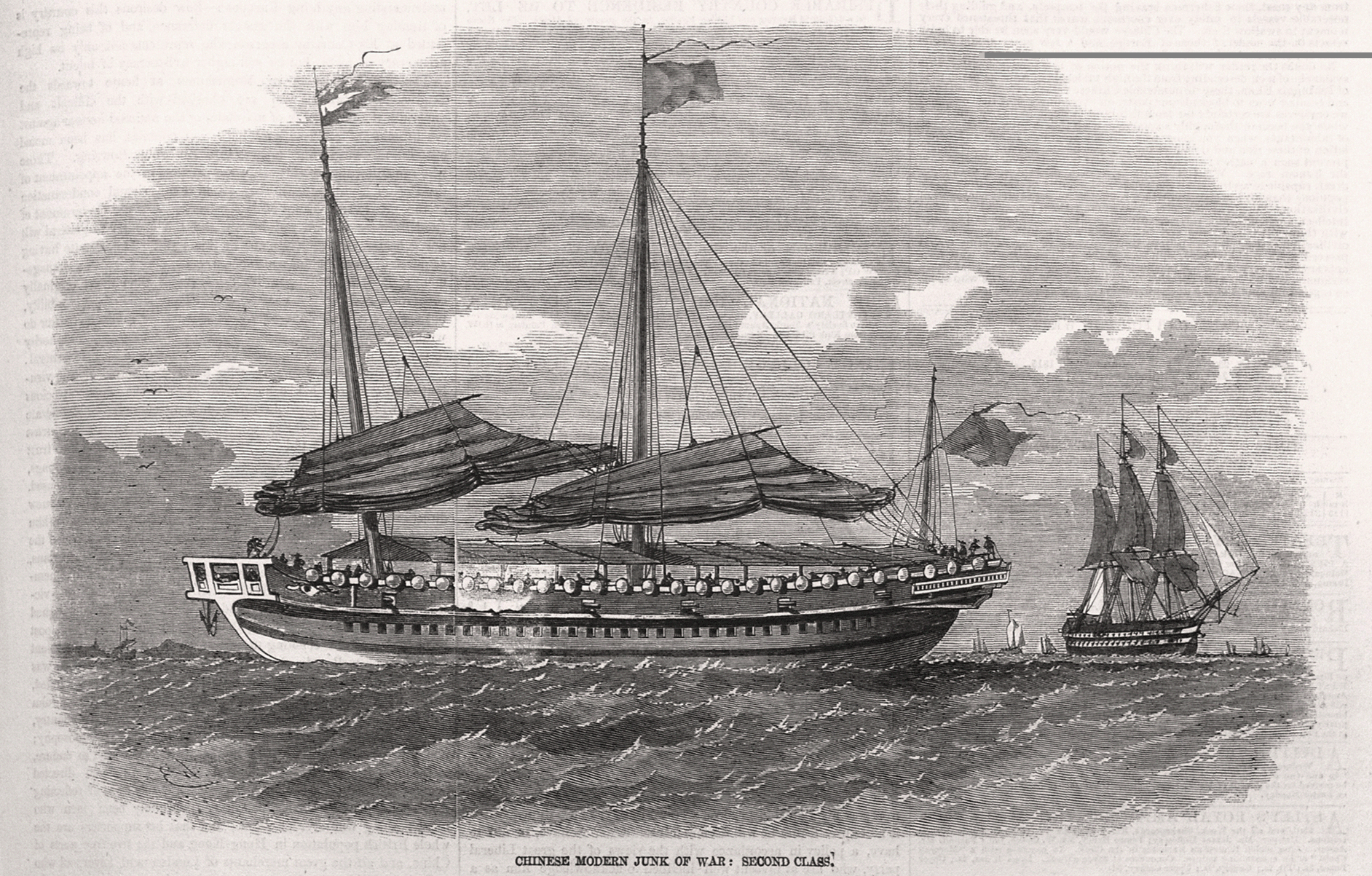

The Chinese war junks in the second Opium War were vastly improved from those of the

first Opium War (1839-1842).

A March 1857 article in the Illustrated London News commented on significant improvements in Chinese naval power, and included an image of a “Chinese Modern Junk of War: Second Class” (below). The warships had added very large guns, bigger than those of the British, and the many small ships excelled in speed and maneuverability. The text cited China’s potential as “a great maritime nation”:

… 20 years ago their ships of war were short, misshapen masses of timber, quaint and ungainly in appearance, almost unmanageable …. the progress of naval architecture in China has advanced far beyond what the people of that country might have been given credit for; and, though still carrying out their eccentric tastes in the more prominent features of their vessels, the shipping of the present day is of excellent and seaworthy character.

…In the lorchas, snake-boats, smuggling craft, pirate junks, and other boats peculiar to the China Seas, the lines of the vessels are of the most beautiful character and they exhibit the greatest speed in all their movements and performances. The armament of war-junks, 20 years ago, consisted principally of matchlocks, mounted on the rails of the bulwarks; at the present time, the junks of the first class carry guns between decks, like our frigates, and of a caliber that has astonished the officers of H.M. ships now in their waters, many of the guns being larger in bore and weight of metal than any we manufacture …. this extraordinary people are calculated and ought to be a great maritime nation.

(The Illustrated London News, March 21, 1857, p. 259)

|

|

|

|

|

| |

“Chinese Modern Junk of War: Second Class.”

The Illustrated London News, March 21, 1857 (p. 259)

MIT Visualizing Cultures

[co2_ILN_1857_0321_159_pg_259]

|

|

| |

Portrait of a Chinese War Junk, ca. 1850

United Art shop at Fo-Shan, Chinese School

“Throughout China's history, junks have been used as war ships. They usually have two or three sails and each mast is made of bamboo because of its strength. This junk is shown in full sail with a large number of figures on board. The warrior’s shields can be seen fixed to the side of the junk in between all the oars. Two lanterns are positioned at the stern with a small cannon in between and there are several guards visible. Small local craft can be seen near the ship, the one to the right is obviously a fishing vessel. The painting was produced for the United Art shop at Fo-Shan and is one of a pair.” (text: National Maritime Museum)

National Maritime Museum

[1850_bhc_Chinese-War-Junk]

|

|

| |

Despite China's improved naval capabilities, British and French steamships equipped

with powerful engines and guns overwhelmed the Chinese junks in battle after

battle.

|

|

| |

“This watercolor depicts an action during the Second Opium War, with a fleet of Chinese junks in the middle distance.” (Text: museum description), watercolor by Thomas Goldsworthy Dutton, 1857

National Maritime Museum

[1857_2nd-Opium-War_nmm ]

|

|

|