| |

PRODUCTION & CONSUMPTION

As the court in China debated opium prohibition, the East India Company developed opium production on an enormous scale in India. The Company established its main production center in Patna, a town in Bihar, 600 kilometers up the Ganges River from Calcutta. There, they forced Indian laborers to work in the extensive poppy fields and prepare the opium in large mixing rooms and examining halls. A skilled workman was required to produce at least 100 balls of opium per day. Then the balls were stacked to be packed in chests made of timber from Nepal. From Patna, a fleet of native boats took the product down the Ganges River to Calcutta.

Two very different runs of graphics produced by eyewitnesses in the 1850s

convey a vivid sense of the production process that was followed throughout most of the 19th century. The first is a spectacular suite of lithographs based on drawings by Walter S. Sherwill, a lieutenant colonel who served as a British “boundary commissioner” in Bengal. The second rendering of different stages of opium manufacture consists of 19 paintings on mica by the Indian artist Shiva Lal. Commissioned by Dr. D. R. Lyall, the East India Company’s “personal assistant in charge of opium-making,” Lal’s work was terminated when Lyall was killed in the 1857 Indian Mutiny.

|

|

| |

Opium Factory at Patna, India

|

|

| |

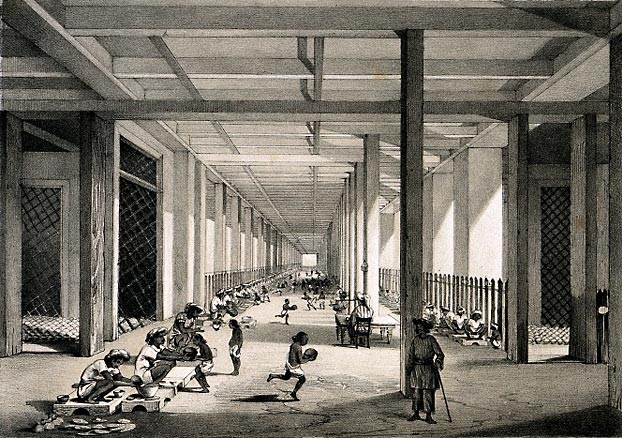

“The Examining Hall, Opium Factory at Patna India”

“In the Examining Hall the consistency of the crude opium as brought from the country in earthen pans is simply tested, either by the touch, or by thrusting a scoop into the mass. A sample from each pot (the pots being numbered and labelled) is further examined for consistency and purity in the chemical test room.”

Prose from The Graphic reproduced in: The Truth about Opium Smoking, 1882

Lithograph after W. S. Sherwill, ca. 1850

Wellcome Images

[1850_Sherwill_1_ExamH1B828]

|

|

| |

“The Mixing Room, Opium Factory at Patna India”

“In the Mixing Room the contents of the earthen pans are thrown into vats and stirred with blind rakes until the whole mass becomes a homogeneous paste.”

Prose from The Graphic reproduced in: The Truth about Opium Smoking, 1882

Lithograph after W. S. Sherwill, ca. 1850

Wellcome Images

[1850_Sherwill_2_Mixing_wlc]

|

|

|

| |

“The Balling Room, Opium Factory at Patna India”

“From the mixing room the crude opium is conveyed to the Balling Room, where it is made into balls. Each ball-maker is furnished with a small table, a stool, and a brass cup to shape the ball in a certain quantity of opium and water called 'Lewa,' and an allowance of poppy petals, in which the opium balls are rolled. Every man is required to make a certain number of balls, all weighing alike. An expert workman will turn out upwards of a hundred balls a day.”

Prose from The Graphic reproduced in: The Truth about Opium Smoking, 1882

Lithograph after W. S. Sherwill, ca. 1850

Wellcome Images

[1850_Sherwill_3_Balling_wlc]

|

|

|

| |

“The Drying Room, Opium Factory at Patna India”

“In the Drying Room the balls are placed to dry before being stacked. Each ball is placed in a small earthenware cup. Men examine the balls, and puncture with a sharp style those in which gas, arising from fermentation, may be forming.”

Prose from The Graphic reproduced in: The Truth about Opium Smoking, 1882

Lithograph after W. S. Sherwill, ca. 1850

Wellcome Images

[1850_Sherwill_4_Drying_wlc]

|

|

| |

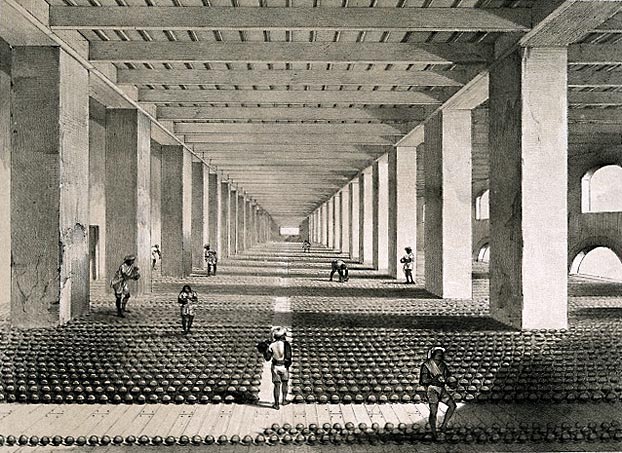

“The Stacking Room, Opium Factory at Patna India”

“In the Stacking Room the balls are stacked before being packed in boxes for Calcutta en route to China. A number of boys are constantly engaged in stacking, turning, airing, and examining the balls. To clear them of mildew, moths or insects, they are rubbed with dried and crushed poppy petal dust.”

Prose from The Graphic reproduced in: The Truth about Opium Smoking, 1882

Lithograph after W. S. Sherwill, ca. 1850

Wellcome Images

[1850_Sherwill_5_Stack1B82D]

|

|

|

| |

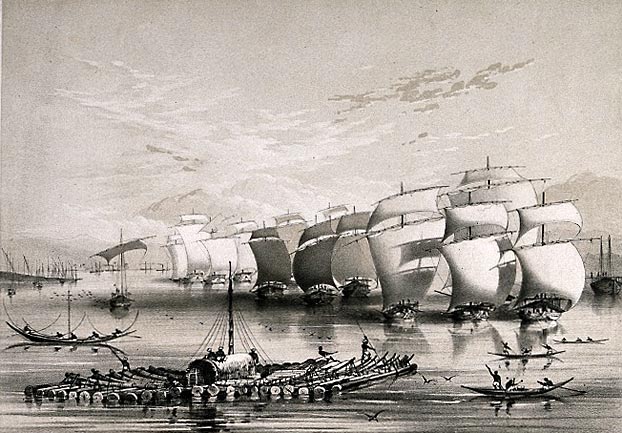

“Opium Fleet Descending the Ganges on the Way to Calcutta”

“An Opium Fleet of native boats, conveying the drug to Calcutta. The fleet is passing the Monghyr Hills, and is preceded by small canoes, the crews of which sound the depth of water, and warn all boats out of the Channel by beat of drum, as the Government boats claim precedence over all other craft. The timber raft shown in the sketch has been floated down from the Nepal Forests, and will be used in making packing-cases for the opium.”

Prose from The Graphic reproduced in: The Truth about Opium Smoking, 1882

Lithograph after W. S. Sherwill, ca. 1850

Wellcome Images

[1850_Sherwill_6_Fleet_wlc]

|

|

| |

Shiva Lal’s Rendering of Opium Manufacture

Commissioned by the East India Company

|

|

| |

Details from an image set illustrating the manufacture

of opium,

1857–60, by Shiva Lal

Victoria & Albert Museum

|

|

| |

Opium Consumption

Opium is a product of the opium poppy (papaver somniferum), which grows widely across the Middle East, India, and Southeast and East Asia. Chinese had known it mainly as a medicinal herb for many centuries. In the 16th century, it appeared in a new form, mixed with a new drug from the New World: tobacco. Along with maize, sweet potatoes, chili peppers, and peanuts, tobacco was one of the crops brought to China by the Spanish and Portuguese. These crops flourished in the hill country of south China, in places where it was difficult to grow rice. The Chinese quickly developed a craving for tobacco, although, as in England, critics attacked it for its addictive and wasteful qualities.

|

|

| |

Opium in the West

The British were not forcing upon the Chinese a commodity that was prohibited in their own country. On the contrary, opium was widely used in Britain and the United States as a medical or pseudo-medical potion, provoking an “anti-opium” movement that grew intense in the late 1800s.

|

|

| |

The Truth About Opium Smoking was published in London in 1882 by the Society for the Suppression of the Opium Trade.

[b_1882_TruthPub1_title_gb]

|

|

|

“The Poor Child’s Nurse” “The Poor Child’s Nurse”

This graphic from an 1849 issue of the British humor magazine Punch addresses

a common practice in 19th-century America as well as England—the widespread use and abuse of opium and opium derivatives (such as laudanum) for relieving illness and even quieting children. By one estimate, at the time of the first Opium War around 300 chests of opium were entering England annually.

Wellcome Library, London

[k_1849_ChildsNurse

_Punch_wlc] |

| |

Madak, or tobacco mixed with opium, originally arrived in south China as part of the global trade with southeast China. Chinese traders had dominated the southeast Asian seas for centuries, mixing with other maritime peoples of the region like the Malays, Arabs, Indians, and Bugis. The European newcomers, especially the Dutch and Portuguese, established fortified trading posts in India, Malacca, and Java, joining a thriving intercultural trading network. Chinese had long consumed exotic products of Southeast Asia like elephant tusks, kingfisher feathers, and sea cucumbers. In the 16th and 17th centuries, they increased their consumption of these tropical luxuries, and opium piggybacked on the expanded southeast Asian trade.

In 1835, a young official named Peng Songyu left Beijing to work in the distant

province of Yunnan and was surprised to discover how widespread opium smoking had become:

When I worked privately for Zhang, the other six colleagues of mine all lived on opium. After lunch, they would each take a lamp and lie down; and they would bring their own pipes to share in the evenings. I worked around them for almost three years, but never tasted the smoke, my hands never touched the tools. All my friends tried very hard to persuade me but I was never moved. They all laughed at me and said that I was willing to suffer. (Cited in Zheng Yangwen, The Social Life of Opium, p.79.)

|

|

|

|

| |

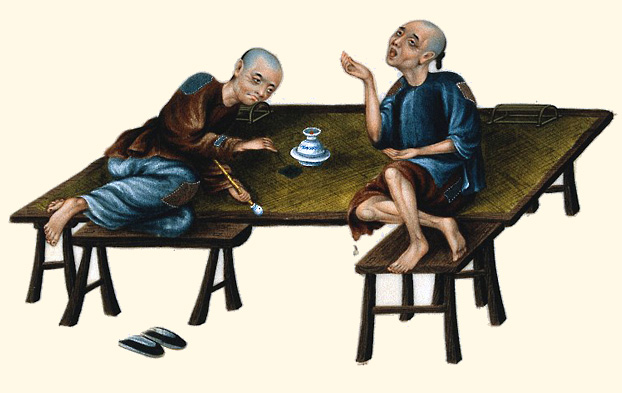

Two 19th-century Chinese images depicting opium smokers:

wealthy (above top) and poor (above).

Unknown Chinese artist, gouache painting on rice-paper

Wellcome Library, London

[1800s_SmokersW_ChPaint_wlc]

[1800s_Smokers_ChPaint_wlc]

|

|

| |

Although opium was a familiar product in China, by the 18th century consumers looked for stronger stuff. During the 18th century, consumption of tropical, addictive, and alcoholic products increased throughout the world. Traders and producers found ways to make these seductive products cheaper, stronger, and more widely available. Vodka consumption in Russia, for example, more than doubled, becoming a cheap source of intoxication, and elites campaigned against it as a moral threat to national life. Americans, for their part, brewed large quantities of fermented apple cider. Tea, coffee, chocolate, tobacco, sugar, alcohol, and opium were some of the addictive stimulants that consumers demanded everywhere. The main British contribution to this trade was to produce opium in a cheap and purified form on plantations in their newly conquered colony of Bengal. Later, they extended production to Patna and Benares upstream on the Ganges. Patna and Benares opium became the most popular brands of this major export commodity and a mainstay of the East India Company’s rule.

Although some opium entered China by land routes from India to Sichuan in the southwest, most of the drugs came by sea and were unloaded at the Lintin rendezvous near Canton. From there, smugglers in their “fast crabs” did not merely transport the opium to ports along the coast, but also carried it by river into the interior. It was this ever expanding corruption of a vast portion of the country that provoked Commissioner Lin’s alarm and righteous indignation.

|

|

|

| |

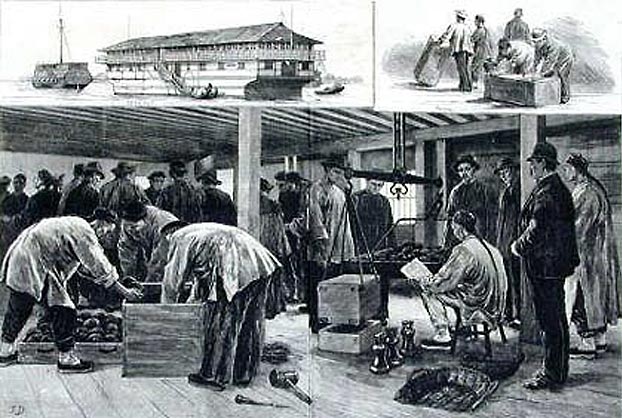

This scene of a huge Chinese holding ship (depicted in full, upper left) depicts foreigners unloading chests of Patna opium and selling it to Chinese intermediaries. The holding ships amounted to floating warehouses, where the drug could be stored for months.

Takao Club website

[1800s_SalePatnaOp_takaoclub]

|

|

| |

“The Opium Trade in China, 1833–1839”

Source: Yangwen Zheng, The Social Life of Opium in China (Cambridge University Press, 2005), p. 71; see also Hsin-pao Chang, Commissioner Lin and the Opium War (Harvard University Press, 1964), 25; also Immanuel C. Y. Hsü, The Rise of Modern China (Oxford University Press, 1970), p. 216.

[1839_map_OpTrade_25]

|

|

| |

Lin’s Pyrrhic Victory

Lin Zexu’s reputation as a great patriot who attempted in vain to defy the Western

imperialists rests largely on two striking actions. The first was a dramatic public spectacle: the destruction, in 1839, of huge quantities of opium that he demanded the British turn over to him. The second act was restrained almost to the point of invisibility: two letters Lin addressed to the then young Queen Victoria, recounting the harm caused by the “poison” of opium and urging her to put the illicit and immoral trade to an end. Lin wrongly assumed that the sale of opium was forbidden in England; and, in any case, the queen never received his fervent entreaty. One of these letters arrived in London in January 1840, carried by a British sea captain whom the Foreign Office refused to recognize. (The translated letter was later printed in the English-language press.)

The prelude to the first of these now-celebrated acts took place in March 1839, when Lin, newly arrived in Canton, demanded that the British surrender their opium stocks. He then proceeded to reinforce this demand in dramatic ways. Two leading hong merchants (Howqua and Mowqua) were arrested and threatened with decapitation; trade in Canton was ordered stopped; Chinese servants and assistants were withdrawn from the foreign factories; and some 350 foreigners were essentially consigned to tedious, uncomfortable detention for what amounted to six weeks.

In these circumstances, the chief superintendent of British trade in China, Captain Charles Elliot, took responsibility for the opium and, in mid May, surrendered 21,306 chests to Lin. Beginning in early June, the opium was destroyed in a flamboyant public spectacle.

|

|

| |

Destroying the Foreigners’ Opium

|

|

|

| |

“Commissioner Lin and the Destruction of the Opium in 1839”

Chinese artist

Hong Kong Museum of Art

[1839_LinDestrOp_165pc_hkma]

In May 1839, in response to Commissioner Lin’s demand that the foreign traders turn over their opium for destruction, Chief Superintendent of Trade Charles Elliot intervened to comply with this demand “on behalf of Her Britannic Majesty’s Government.” This seemingly magnanimous gesture was, as one Western China merchant phrased it, a clever “snare,” for it made the Chinese “directly liable to the British Crown.” In short time, the British government would trip this snare and demand compensation for the opium that was handed over.

All told, Elliot delivered 21,306 chests of the drug to the Chinese. This was an enormous amount: at roughly 140 pounds per chest, Lin suddenly found himself with three-million pounds of opium on his hands. This was destroyed over a period of 23 days in June 1839, at Chuanbi by the bay at Canton. The process required the labor of around 500 workers and involved three huge trenches (150 feet long, 75 feet wide, and 7 feet deep) lined with stone and timber and filled with approximately two feet of water from a nearby creek. The opium balls were broken into pieces, dumped into the trenches, and stirred until dissolved, after which salt and lime were added, creating noxious clouds of smoke. The “foreign mud” was then diverted to the creek and washed out to sea.

Lin and around 60 Chinese officials, together with foreign spectators, observed the destruction from an elaborately decorated pavilion erected nearby. In a little known coda to this famous event, Lin also offered prayers to the spirit of the Southern Sea, apologizing for poisoning its domain with these impurities and advising the deity (as the historian Jonathan Spence has recorded) “to tell the creatures of the water to move away for a time, to avoid being contaminated.” |

|

|

| |

British Museum

[1839_LinDestrOp_1909print]

The above often-reproduced woodcut of Commissioner Lin destroying the British opium at Canton was first published in 1909, in the September 22 issue of the newspaper Shishibao Tuhua, as part of a series titled “Portraits of the Achievements of Our Dynasty’s Illustrious Officials.” The Chinese text perpetuates some misinformation about this famous event, but effectively conveys both the enduring admiration of Lin’s act and the abiding sense of outrage at the ongoing opium trade. (The opium was not burned, as stated, but rather gave off toxic fumes when dissolved in a mix of water, salt, and lime; and British ships were never extensively damaged or destroyed in the manner claimed.) The full Chinese text on this image translates as follows:

Lin Zexu Burns the Opium Lin Zexu Burns the Opium

In 1839, Lin Zexu arrived as Governor-general of Liangguang, and discovered that Western merchants held opium stores of 20,283 chests. He burnt them all on the beach. Later other foreign ships secretly stole into port with more opium. Lin took advantage of a dark night when the tide was low to send crack troops to capture them. He burnt 23 ships at Changsha bay. Subsequently, because these actions caused a diplomatic incident [i.e. the Opium War], opium imports kept on growing. Now the British government agrees that we must eliminate the poison of opium. Reflecting on past events, we have turned our misfortunes into a happy outcome.

|

|

| |

Lin’s apparent triumph of June 1839 turned out to be a delusion, for the British

seized on the destruction of the opium to demand retaliation and redress. Debate in Parliament was heated and protracted. Hawks called for war against the obstructionist empire that refused to recognize the blessings of “free trade.” Doves, essentially agreeing with the Chinese, countered that the opium trade was immoral and a stain on Britain’s reputation.

When William Gladstone, the leading Tory politician, argued that opium was a pernicious commodity and hostilities against China would be “unjust” and “cover this country with permanent disgrace,” Lord Palmerston, the foreign secretary, replied that China itself had created the demand for opium, and its people were merely “disposed to buy what other people were disposed to sell them.” At the same time, however, Palmerston himself had reservations about the illicit trade, and even more pressing concerns about the practical consequences of committing forces to China. Indian troops were already preoccupied with Russian threats to Afghanistan, while the royal navy was concerned about guarding the eastern Mediterranean against Ottoman threats.

Tensions increased in July when six drunken British seamen on shore leave in Kowloon (Jiulong)—located near Hong Kong and across from Macao at the mouth of the Canton estuary—vandalized a temple and killed a local man in a brawl. When the British refused to hand over anyone for trial under Chinese justice, arguing that the Chinese would use torture to force confessions, Lin responded by stopping trade, poisoning some wells, and prohibiting sale of food to the foreigners. Rumors arose that the Chinese planned to seize British property in Macao, prompting an exodus to Hong Kong of scores of ships and around 2,000 foreigners.

All this precipitated the first skirmish of the still undeclared war. On September 4, 1839, after Captain Elliot and his interpreter Karl Gützlaff failed to persuade Chinese naval officers in the straits between Hong Kong and Kowloon to let them purchase food and water, two small British warships opened fire on war junks anchored off Kowloon. Three junks were damaged before the British ran low on ammunition and withdrew. Casualties were low, and the confrontation amounted to a stalemate.

Two months later, it became clear that all hope for a peaceful resolution of these rising tensions was out of reach.

|

|

| |

|

|

|