| |

In January of 1934, a strange horseman appeared on the crowded and colorful magazine racks along Shanghai’s “culture street,” Fuzhou Road. His body a stout black ink bottle, a straight-edge at his hip for a sword, a drafting triangle for a shield, and his lance a steel-nibbed pen, this was clearly a warrior. Yet a bright red heart painted on his breast seemed to give this unlikely looking knight a mandate of compassion. As for his mount, it, too, was assembled from the western-style artist’s stock-in-trade, but for a Chinese brush pen protruding from behind.

Equal parts comic and gallant, this strange horseman heralded the arrival of the longest running and most influential humor and satire magazine in China during the first half of the 20th century: Shidai manhua, or by its English name, Modern Sketch. Published monthly for 39 issues from 1934 through June 1937, Modern Sketch was recognized then, and still is now, as the centerpiece of China’s golden era of cartoon art.

|

|

Images in this unit, unless otherwise noted, are from Modern Sketch (Shidai manhua),

Shanghai, 1934-1937, courtesy Colgate University Library. |

|

| |

THE TURBULENT ‘30s

There are many reasons Modern Sketch stands out among the array of nearly 20 illustrated humor and satire magazines that made the mid-1930s such an exceptional time for China’s popular graphic art. One can point to Modern Sketch’s longevity, the quality of its printing, the remarkable eclecticism of its content, and its inclusion of work by young artists who went on to become leaders in China’s 20th-century cultural establishment. But from today’s perspective, most intriguing is the sheer imagistic force with which this magazine captures the crises and contradictions that have defined China’s 20th century as a quintessentially modern era. |

|

|

| |

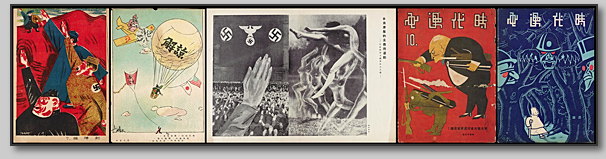

Published in Shanghai monthly from January 1934 to June 1937, Modern Sketch conveyed a range of political and social commentary through lively and sophisticated graphics. Topics included eroticized women, foreign aggression—particularly the rise of fascism in Europe and militarized Japan, domestic politics and exploitation, and modernity-at-large as envisioned through both the cosmopolitan “Modern Girl/Modern Boy” and the

modernist grotesque.

August 1934 [ms08_000] October 1934 [ms10_000] November 1934 [ms11_000]

December 1934 [ms12_041] April 1935 [ms16_046] August 1935 [ms20_000]

|

|

| |

Modern Sketch could be incisive, bitter, shocking, and cynical. At the very same time it could be elegant, salacious, and preposterous. Its messages might be as simple as child’s play, or cryptically encoded for cultural sophisticates. Modern Sketch was many things for its many readers. The democracy of popular artistic forms it hosted, united in the mission of fusing art and the era, made it a landmark publication.

|

|

| |

Contributors to Modern Sketch critiqued current politics and society with an array of styles and genres that defies generalization.

|

|

Lu Shaofei Lu Shaofei

“Peace No More”

June 1935 [ms18_042] |

Yu Weizi

“Elucidation through Tinted Lenses”

December 1935 [ms24_000] |

Wang Zimei Wang Zimei

“Hung by the Heels

in Hell”

June 1937 [ms39_010] |

Dou Zonggan

“As If Confronting

a Mortal Foe”

January 1936 [ms25_010] |

| |

Epoch and Image

Borrowed from the Japanese word jidai, the shidai in Shidai Manhua might be more literally translated as “epoch” or “era”; that is, a discrete period of historical time coming after a past era and, presumably, before a future era, with each marking a segment along a linear, evolutionary progression.[2] For educated urban Chinese in 1934, a number of recent epochal events, both political and material, gave cause to believe that they were, or at least ought to be, living in a new, and very modern, shidai.

|

|

Huang Jiayin Huang Jiayin

“There’s No Comparing

the Past and Present...”

(detail highlighted in red)

May 1935 [ms17_025]

|

|

| |

The most fundamental political event had been the collapse of China’s dynastic system just over two decades earlier, in 1911. The Republic of China that replaced it, while modern in aspiration, spent its first several decades struggling with territorial fragmentation and reactionary coups. Less than a decade later, in 1919, China’s educated elite asserted a new national consciousness during what came to be called the May Fourth Movement, a broad-based protest against imperialism coupled with efforts to modernize China’s cultural tradition by introducing new, enlightened, and mostly foreign-inspired literature, art, and thought.

|

|

Wang Zimei Wang Zimei

“The May Fourth Period”

A panel from the

“Illustrated Record of

Lu Xun’s Struggles”

(detail highlighted in red)

November 1936 [ms32_034]

|

|

| |

From 1926 to 1928 another wave of nationalism swept the country. Culminating in the Northern Expedition that marched up from the southern province of Guangzhou, this second revolution temporarily united the country’s antagonistic Nationalist and Communist camps with the patriotic goal of completing the unfinished work of 1911. On its way north, idealistic members of the Expedition agitated against repressive traditionalism, challenged the imperialist occupiers in China’s treaty port cities, and rolled back the influence of regional militarists who had filled the power vacuum following the end of dynastic rule.

|

|

|

In April 1927, however, the march north exploded in a notoriously bloody purge of communists. The mastermind of this political violence, “Generalissimo” Chiang Kai-shek, then led the country through the Nanjing Decade (1927 to 1937), 10 years of relative stability during which Modern Sketch and other cultural enterprises thrived in China’s large coastal cities. In April 1927, however, the march north exploded in a notoriously bloody purge of communists. The mastermind of this political violence, “Generalissimo” Chiang Kai-shek, then led the country through the Nanjing Decade (1927 to 1937), 10 years of relative stability during which Modern Sketch and other cultural enterprises thrived in China’s large coastal cities.

|

As pictured in Hu Kao’s group caricature “Big Names of the Day,” Chiang Kai-shek has an outsized fist relative to a puny head—a veiled commentary on the Generalissimo’s tendency to apply brawn instead of brains when resolving problems of state. As pictured in Hu Kao’s group caricature “Big Names of the Day,” Chiang Kai-shek has an outsized fist relative to a puny head—a veiled commentary on the Generalissimo’s tendency to apply brawn instead of brains when resolving problems of state.

(detail highlighted in red)

January 1935 [ms01_016] |

|

|

| |

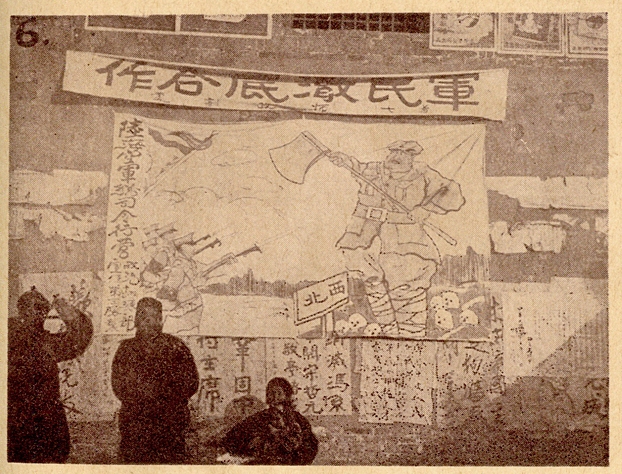

Trouble with regional militarists or “warlords” did not end with the Northern Expedition. This photo from the pictorial magazine Modern Miscellany shows a propaganda cartoon posted during the Central Plains War of 1929-1930, when a group of regional militarists—including the “Christian General” Feng Yuxiang, pictured holding an axe in field of skulls—tried in vain to break with Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist Government.

Shidai Huabao, 1929, no. 2, p. 24,

Courtesy of Shanghai Library

[ms404]

|

|

| |

The material impact of the modern hit with greatest force in China’s major treaty ports. These cities, which developed on the basis of “unequal treaties” successively instituted after the First Opium War in 1842, numbered nearly 80 by the end of the 19th century. The largest and most developed treaty ports—Tianjin, Guangzhou, Hankou, and above all Shanghai—experienced a welter of technological and demographic changes that set them apart from the inland regions, especially from the 1910s onward when international trade burgeoned. The look and—depending on one’s economic means—the practice of everyday urban life was radically transformed. Most striking to all newcomers were the steel-framed, multi-story buildings that loomed above major streets, like Shanghai’s riverside financial avenue the Bund and its prosperous main shopping thoroughfare, Nanjing Road. Closer to ground level were any number of new technological introductions, from automobiles to rolled cigarettes, as well as new places of entertainment, from coffeehouses and movie theaters to hotels doubling as brothels. All were absorbed by the era’s popular culture as emblems of the joys, evils, and rampant incongruities of urban treaty-port living.

|

|

| |

Visual Narrative: City Life

The modern city provided endless inspiration for the artists of Modern Sketch. Some took their images directly from life, others concocted fantastic imaginary tableaux. The finest and most ambitious depictions of city life express a deeply ambiguous mixture of fascination and repulsion.

|

|

Zhang Guangyu Zhang Guangyu

“Bumpkin One (looking at the Park Hotel): What’s that there big building fer?

Bumpkin Two: Dontcha know? It’s bilt in case the Huangpu River floods!”

March 1935 [ms15_015]

|

|

| |

This page of single-panel gags develops the theme of “Women and New Knowledge.” The modern topics covered include café waitresses, foreign cinema, celebrity athletes, and fashion.

April 1935 [ms16_028]

|

|

Chen Paiyi

Chen Paiyi

Waitress: Would you like anything else, sir?

Customer (just released from prison): Give me a minute to think about that...

Yu Suoya

Jinggui (girlfriend of an athlete): Oh, now I understand. All the girls are in love with athletes. Loved by one and all... Well, who gives a fig about that!

|

Liu Chuliang

Liu Chuliang

- Why is she staring up at the sky?

- Doesn’t like his looks, I guess.

Liu Wenxian

Miss Yang: What’s with your constantly going in and out every day lately?

Miss Pei: You didn’t notice? I’ve just made myself some new outfits!

|

| |

Wang Dunqing

“Negotiating”

Anti-prostitution campaigns in Shanghai drove many women to do their business in collaboration with hotels. The writing on the entranceway

reads “Shanghai Hotel.”

January 1935 [ms13_020]

|

|

| |

The booming international trade financing these material changes transformed the human landscape, too. Largest among the treaty ports, Shanghai was divided into three independent municipalities: the International Settlement, the French Concession, and the Chinese-controlled areas. The former two zones were governed by councils comprised of wealthy, property-owning residents, while the parts of the city governed by the Chinese—Greater Shanghai—were headed by a mayor, appointed through the central government in Nanjing.

|

|

| |

Lu Zhixiang

“The New Climate for the Sub-colonial”

For regular Chinese like the blue-clad worker depicted here, treaty-port life was partitioned by hard boundaries of class and race.

January 1935 [ms13_022]

|

|

| |

By 1934 a steadily increasing foreign population had been concentrated in the city’s foreign concessions for nearly 100 years. Between 1915 and 1930, however, the number of foreign nationals doubled in response to a spurt of economic growth during and after the First World War. Japanese and British topped the list, ahead of White Russian émigrés, Americans, German, Portuguese, and French, as well as “colonials” like Sikhs and Annamites (Vietnamese), not to mention the multinational sailors, soldiers, and tourists from all over the globe who steamed in and out of China’s ports. Though far outnumbered by the Chinese population, the foreign presence in Shanghai and other coastal cities became an integral part of the modern mélange of sights and sounds, mediated on the street by the urban lingua franca, pidgin.

|

|

|

Wang Dingjie Wang Dingjie

American and European sailors on shore leave were a frequent sight in Shanghai and other coastal treaty-port cities. The caption explains that kumishow means “commission,” in this case referring to a

tip or gratuity.

January 1937

[ms_34_008]

|

| |

Hua Junwu

“Tour Group” (detail)

In the 1930s Shanghai was a major international tourist destination.

May 1935 [ms17_011]

|

|

| |

The artists of Modern Sketch also depicted local Chinese street life. This panel from Chen Haoxiong’s “Pursuit of Low-brow Entertainment” shows residents of Shanghai’s overcrowded nongtang row houses craning to view itinerant performers put on a show of Cantonese opera. Some “modern” touches here include electric wires and an improvised radio antenna (highlighted in red).

January 1936 [ms25_029] detail

|

|

| |

By the 1930s the idea of shidai not only permeated talk of history, politics, and society, the term itself had become a buzzword used to promote products from furniture to face cream. Thus the magazine buyer on Fuzhou Road, in addition to intuiting a sense of epochal change from the title of Modern Sketch, would probably have been aware, too, that this name linked our strange horseman to a carefully branded line of popular periodicals put out by an ambitious new company: Modern Publications Ltd. In 1934, Modern Publications initially featured four magazines alongside Modern Sketch: the glossy, sophisticated monthly Van Jan, the mass-market pictorial Modern Miscellany, the cinema-goer’s companion Modern Film, and the humor magazine Analects.

|

|

| |

Modern Publications Ltd.

Eye-catching popular periodicals from Modern Publications were one reason 1934 was dubbed Shanghai’s “Year of the Magazine.”

In the city’s intensely competitive publishing market,

image was everything.

|

|

Cartoonist and commercial artist Zhang Guangyu’s June 1934 cover of Van Jan fancifully depicts a future world, long after the demise of human beings, in which robots battle dinosaurs in dense jungle. Cartoonist and commercial artist Zhang Guangyu’s June 1934 cover of Van Jan fancifully depicts a future world, long after the demise of human beings, in which robots battle dinosaurs in dense jungle.

Courtesy of Shanghai Library

[ms303_Wanxiang_00]

|

|

| |

The Chinese titles for each of Modern Publications’ “Five Big Periodicals” (highlighted in red) featured custom-designed typefaces, likely created by Zhang Guangyu. From top to bottom, the names refer to Van Jan, Modern Miscellany, Analects, Modern Sketch, and Modern Film.

Courtesy of Shanghai Library

[ms303_Wanxiang_00]

|

|

| |

A richly colored cover design from Modern Miscellany

(highlighted in red) as printed in an advertisement in Van Jan.

(full page and enlarged detail)

Courtesy of Shanghai Library

[ms305_Wanxiang_03_44]

|

|

| |

However varied and experimental the content of its periodicals, Modern Publications was from start to finish a money-making venture, funded in the main by Shao Xunmei, a high-born Shanghai sophisticate, poet in the decadent mold, and cynosure of the city’s literary and art circles. In a last-ditch effort to save his extended family from bankruptcy, Shao had invested a small fortune to purchase cutting-edge rotogravure printing machinery and photographic equipment from Germany. The physical plant these machines comprised formed the industrial heart of his publishing empire, The Modern Press.[4]

|

|

|

| |

“Portrait of a Literary Gathering”

This elaborate group caricature, unsigned but usually attributed to Lu Shaofei—the editor of Modern Sketch—shows the founder of Modern Publications Shao Xunmei at the table’s head (highlighted in red), hosting an imaginary soiree of Shanghai writers. Shao is seated between portraits of Maxim Gorky and the late-Ming writer Yuan Zhonglang, suggesting the range of literary styles his periodicals supported.

The original drawing appeared in the February 1936

issue of the magazine Six Arts (Liu yi).

[ms402]

|

|

| |

Logo for The Modern Press, designed by Zhang Guangyu.

From Zhang’s 1932 book Modern Commercial Art (Jindai gongyi meishu)

Courtesy of Shanghai Library

[ms401]

|

|

| |

No less impressive than the technology behind Modern Publications was the pool of contributors to Shao’s stable of popular-press magazines. For instance, in its brief, three-issue lifetime, Van Jan alone published the work of Shanghai’s most fashionable pop-modernist writers, such as Shi Zhecun, Liu Na’ou, Mu Shiying, and Ye Lingfeng. Modern Publications also engaged the talents of a group of graphic artists who had joined forces some seven years before to produce the predecessor to Modern Sketch, a large-format weekly that ran from 1928 to 1930 called Shanghai Sketch (Shanghai manhua).[5] Known for its provocative cover art, Shanghai Sketch informed its readers with photojournalistic content, kept them abreast of the latest doings in local artistic and social circles, and entertained with several pages per issue of humorous, satirical, fashion-related, and fine-art illustration.

|

|

Cover illustration entitled “Degeneracy” (Duoluo) from the November 23, 1929 issue of Shanghai Sketch, the forerunner to Modern Sketch.

Cover illustration entitled “Degeneracy” (Duoluo) from the November 23, 1929 issue of Shanghai Sketch, the forerunner to Modern Sketch.

The artist, once again Zhang Guangyu, has superimposed a nude woman against the five lobes of a fallen, tattered leaf from a plane tree, the kind planted along the boulevards of Shanghai’s French Concession. A disturbing image, to be sure, but one that condenses the ideas of seasonal content, fallen women, a quarter of the city notorious for vice, anxiety over sociopolitical decline, and the period’s bohemian vogue for decadent-style poetry and art.

[ms207]

|

|

|

It is also conceivable that Zhang’s leaf motif was a good-natured gibe aimed at his junior, unmarried colleague at Shanghai Sketch, Ye Qianyu, whose surname means “leaf.” It is also conceivable that Zhang’s leaf motif was a good-natured gibe aimed at his junior, unmarried colleague at Shanghai Sketch, Ye Qianyu, whose surname means “leaf.”

Plane tree leaves, like the one shown in this recent photograph, can still be found littering the sidewalks in Shanghai’s former French Concession during the late autumn months.

[ms403]

|

| |

Cartoon Art from the ’20s to the ’30s

It is important to keep in mind that the English word “cartoon” can be a misleading translation for the Chinese term manhua. Cognate with the Japanese word “manga,” Chinese magazines like Shanghai Sketch (Shanghai manhua) and Modern Sketch (Shidai manhua) expanded the meaning of manhua to cover a diversity of graphic forms beyond what we normally think of as “cartoons.” We can see some of the evolution of manhua by looking at “before and after” samples of work by artists who contributed to both Shanghai Sketch in the late 1920s and Modern Sketch in the mid-1930s.

Zhang Guangyu

|

|

|

“Mechanical Movement” “Mechanical Movement”

Shanghai Sketch, November 24, 1928

Courtesy of Shanghai Library

[ms204]

|

“Stalin, the Steel-armed Soviet God and Roosevelt, the American Blue Eagle Emperor,” Van Jan, May 1934 “Stalin, the Steel-armed Soviet God and Roosevelt, the American Blue Eagle Emperor,” Van Jan, May 1934

Courtesy of Shanghai Library

[ms301] |  |

| |

Zhang Yingchao

|

|

|

“Study hard “Study hard

today, strike it

rich tomorrow.

Such joy!”

Shanghai Sketch, June 1, 1929

[ms205]

|

“The Song of Spring” “The Song of Spring”

Modern Sketch,

February 1935

[ms_14_022]

|  |

| |

Lu Shaofei

|

|

|

“Flower of Society”

Shanghai Sketch, August 11, 1928

[ms201]

|

“The Secret to Raising Money” “The Secret to Raising Money”

Modern Sketch, February 1934

[ms02_018]

|  |

| |

Ye Qianyu

|

|

“The Era of Youth” “The Era of Youth”

Shanghai Sketch, April 19, 1930

[ms208]

|

“Latest Floral Pattern, Indigo on White” “Latest Floral Pattern, Indigo on White”

Van Jan, May 1934

Courtesy of Shanghai Library

[ms302] |

| |

Crises and Visions

The art of Shanghai Sketch anticipated what was to appear in Modern Sketch half a decade later. But as its name suggests, the earlier magazine’s symbolic center of gravity lay in the city of Shanghai, with all its distinct character types, mercurial fashions, and urban absurdities. Modern Sketch was also embedded in the Shanghai urban milieu, but cast its net much wider. In part, this widened scope can be attributed to national and global crises that had intervened since 1930 and continued throughout Modern Sketch’s lifetime. That decade began with the Japanese military takeover of China’s Northeast in 1931 and subsequent establishment of the colonial puppet-regime Manchukuo, a catastrophe that galvanized elite nationalist sentiment.

|

|

|

Wang Zimei Wang Zimei

“Twelve Animals of the Zodiac”

caricaturing the puppet-emperor

of Manchukuo, Pu Yi

(detail highlighted in red)

December 1936 [ms33_007]

|

|

Lu Fu Lu Fu

“Heaven, Earth, Emperor,

Ancestor, Sage”

(detail highlighted in red)

February 1936 [ms26_033] |

| |

In January 1932, Shanghai itself became a battlefield when Japanese forces attacked the city in the Song-Hu War. The furious shelling, bombing and street fighting, incited by a territorial dispute between the Nationalist Government and Japan, devastated entire neighborhoods—and in fact interrupted Shao Xunmei’s publishing ambitions until the city had recovered.[7] As Japanese aggression loomed larger on the horizon, global depression disrupted China’s rural and urban economies even as it boosted fascist movements in Germany, Italy, Japan, and right in China’s own ruling Nationalist Party.

|

|

Ye Qianyu Ye Qianyu

“The New Lines of Battle?”

Ye depicts Mussolini, Hitler, and in the background, a figure probably representing Japan. Note that Hitler’s salute blocks the face of the figure in a Chinese cap and scholar’s robe. China’s ruling Nationalist Party had a powerful fascist faction during the 1930s, to which Ye discreetly alludes.

January 1935 [ms01_018]

|

|

| |

Visual Narrative: The New World Dis-Order

The print-run of Modern Sketch from 1934 to 1937 placed it squarely athwart a dangerous age of global uncertainty. These were years when fascism squared off with communism, and liberal nations sparred weakly against expansionist powers like Germany, Italy, and Japan. Many Chinese saw themselves threatened on all sides by imperialist aggressors, most urgently Japan, which by 1936 virtually controlled all of north China. Dramatic international events, like the League of Nations’ abandonment of King Haile Selassie’s Ethiopia to the invading Italian fascists were, for China, the writing on the wall. Even China’s “goose egg” showing of zero medals in the 1936 Berlin Olympics seemed to bode ill in a world where might trumped right at every turn.

|

|

|

Internationally and domestically, forces of the left confronted those of the right, with the Soviet Union facing off against European fascism, and China’s own communist movement struggling to survive, underground in the cities and aboveground in isolated rural bases. Internationally and domestically, forces of the left confronted those of the right, with the Soviet Union facing off against European fascism, and China’s own communist movement struggling to survive, underground in the cities and aboveground in isolated rural bases.

|

|

Huang Baibo

details from “Left and Right”

March 1937 [ms36_006] |

|

But Modern Sketch did much more than react to big national and global events. Due to the vision of its editor, Lu Shaofei, the collective pictorial imagination of Modern Sketch probed all corners of the modern era, beyond and below the big stories of politics, economics, Shanghai, and even China. But Modern Sketch did much more than react to big national and global events. Due to the vision of its editor, Lu Shaofei, the collective pictorial imagination of Modern Sketch probed all corners of the modern era, beyond and below the big stories of politics, economics, Shanghai, and even China.

|

Lu Shaofei at work on

Modern Sketch. A copy

of issue 3 can be seen

beside his elbow.

Van Jan, May 1934

Courtesy of Shanghai Library

[ms306] |

| |

Lu introduced his editorial philosophy unobtrusively, as if giving implicit privilege to images over words, in a brief note tucked into the lower right corner of the last page of Modern Sketch’s inaugural issue, the same one that featured the strange horseman on its front cover:

|

|

|

On all sides a tense era surrounds us. As it is for the individual, so it is for our country and the world. Will things always be this way? I for one don’t know. But since the feeling won’t go away, one desires an answer, and the more one fails to find it, the more that desire grows. Our stance, our single responsibility, then, is to strive! As for the design on the cover of this first issue, it shall be our logo. Its meaning: Yield to None. On all sides a tense era surrounds us. As it is for the individual, so it is for our country and the world. Will things always be this way? I for one don’t know. But since the feeling won’t go away, one desires an answer, and the more one fails to find it, the more that desire grows. Our stance, our single responsibility, then, is to strive! As for the design on the cover of this first issue, it shall be our logo. Its meaning: Yield to None.

|

Inside last page of the first

issue of Modern Sketch

(detail highlighted in red)

January 1935 [ms01_034] |

|

| |

Knowing but ambiguous, brave yet vague, Lu’s quiet manifesto invites the reader to join the strange horseman on a mission to make sense of extreme times, a shidai like no other. As for the horseman, suspended in a space deliberately left blank, it seems poised to engage all comers, known and unknown, with the tools of the cartoon artist’s trade. But what, precisely, were these “cartoons,” these “manhua,” these “sketches” that would take on the modern era?

|

|

|