|

|

With the Meiji Restoration in 1868, Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847-1915), who had fought on the side of the defeated Tokugawa shogun, retreated to the provinces for a hiatus of six years. He finally returned to the capital in 1874. Between 1876 and 1881, he produced an unusual series of woodblock prints titled “Famous Places of Tokyo.” These elegant views convey a sense of both change and loss strikingly different from the brightly colored prints of his contemporaries that celebrated Westernization in all its forms.

Kiyochika’s return to Tokyo coincided with the beginning of Tokyo’s gas-lit era. Street lighting dramatically changed the look of the city after dark, opening up a whole new field of visual investigation for artists. For Kiyochika, the impact was momentous. Twenty-five out of the ninety-three prints in his series (called Tokyo Meisho-zu in Japanese) are nightscapes. No other woodblock print series juxtaposes the vanishing and emerging Japan more evocatively.

|

|

|

Unless otherwise noted, all images in this unit are from the Robert O. Muller Collection of the Freer Gallery of Art and the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

| |

|

| |

INTRODUCTION

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847-1915) emerged from virtually nowhere. Born into a family of low-ranking officials in charge of government rice granaries in the Honjo district of Edo, his parents were members of the sprawling bureaucracy that served the Tokugawa family who had ruled Japan as hereditary shoguns since the beginning of the seventeenth century. Kiyochika’s childhood and youth and unpredictable development as an artist coincided with an epoch of enormous political and social upheaval in Japan. |

|

| |

Kiyochika was around six years old when Commodore Matthew Perry of the United States brought his gunboats to Japan—not once but twice (in 1853 and 1854)—and forced the Tokugawa regime to open the secluded country to foreign trade and intercourse. He was twenty-one in 1868, when the Tokugawa shogunate was overthrown, bringing to an end over six centuries of feudal rule by the samurai class. |

|

|

Photograph of Kobayashi Kiyochika

(Japanese, 1847-1915), Meiji era

|

| |

His emergence as an artist in the woodblock-print tradition in the 1870s occurred at a time when many fellow artists were caught up in producing colorful “brocade pictures” (nishiki-e)—also called “enlightenment pictures” (kaika-e)—that celebrated the abrupt “Westernization” of Japanese life. This was, as it transpired, a celebration that the young Kiyochika by and large resisted.

Despite their status as minor civil servants, Kiyochika’s family lived on the edge of poverty. The price of rice was a source of constant turbulence in an age of social, political, and commercial upheaval, and the family relied on a meager stipend to survive. The death of Kiyochika’s father when his son was still in his fifteenth year was a devastating blow to family fortunes, and the collapse of the feudal order soon after cast Kiyochika and his family to their own devices. Still, when the Tokugawa regime was overthrown in 1868, Kiyochika followed the last shogun in self-imposed exile in Shizuoka.

During his years in Shizuoka, Kiyochika tried his hand at various odd jobs from fencing master to fisherman, and became familiar with the shabby world of traveling entertainers. His illustrated diaries affirm that he had fledgling skills as an artist, although he never was able to afford sustained formal training in traditional painting or woodblock printing. Yet in 1874, on a whim, he returned to Edo—now renamed Tokyo—and soon afterwards emerged as a woodblock-print artist of note.

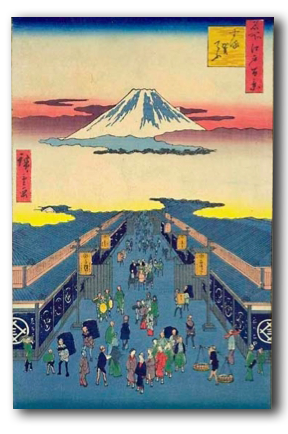

Beginning in 1876, Kiyochika embarked on an unfinished series of ninety-three views of the new capital city that now stands as his main claim to fame in modern Japanese art. Titled Famous Places of Tokyo (Tokyo Meisho-zu), his obvious inspiration was Andō Hiroshige’s 100 Famous Views of Edo (Meisho Edo Hyakkei), which Hiroshige began serializing in 1856, when Kiyochika was a youngster, and continued until his death in 1858. (Publication was completed in 1859.) This immensely popular series went through many printings, and eventually became known and admired by Western artists such as Vincent Van Gogh.

|

|

|

|

Four prints from Hiroshige’s 100 Famous Views of Edo,

published between 1856 and 1859, when Kiyochika was a youth.

Left to right: numbers 6, 13, 90, 111.

[www.hiroshige.org.uk]

|

|

| |

Hiroshige’s colorful and exquisitely composed prints carried the vivaciousness of the popular woodblock-print tradition to new levels. His “famous views of Edo,” however, present a very different picture than the “Tokyo” Kiyochika observed when he returned to the renamed city less than twenty years later. Hiroshige’s renderings are romantic, absent Western influences, often almost pastoral, and more often than not sparkling under a midday sun. Kiyochika’s city, by contrast, is somber and austere. Western intrusions are noticeable, although often just marginally, in the form of telegraph wires, gaslights, and brick buildings. Gradations of light fascinated him, shading into twilight and deepest night. The prevailing mood is one of melancholy.

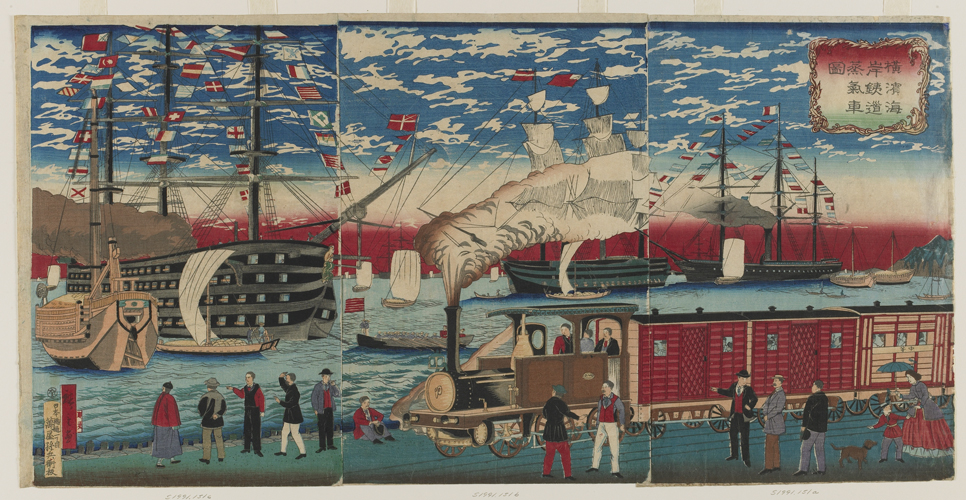

Such themes and preoccupations did not set Kiyochika apart from just his distinguished predecessor, Hiroshige. They also set him apart from contemporary printmakers who cast the bright light of day on all manner of Western manifestations in the “new” Japan: gaslights and telegraph wires and Western-style buildings, to be sure, but also steamships and trains, upper-class men and women playing classical Western music, doyens of high-society (including the emperor and empress) dressed in the latest European fashions. These early Meiji-era “Westernization” prints commonly took the form of expansive and gaudy triptychs. They are what usually come first to mind when one hears the words “Meiji prints.”

|

|

|

| |

Utagawa Hiroshige lll,

“Locomotive Along the Yokohama Waterfront,”

woodblock print, 1871

[s1991.151a-c]

|

|

| |

Utagawa Hiroshige lll,

“Famous Views of Tokyo: Brick and Stone

Shops on Ginza Avenue,” woodblock print, 1876

[s1998.32a-c]

|

|

| |

Kiyochika was a bystander to this flamboyant printmaking. Rather than celebrate (and exaggerate) all that was Western and new, the views of the capital he produced between 1876 and 1881 are restrained single-block prints that reflect Western influences in more subtle ways. There is some indication, for example, that he may have studied the technical teachings of Charles Wirgman (1832-1891), an English artist and cartoonist who lived in Japan from 1861 and trained many local artists in Western techniques of pictorial representation. Kiyochika’s works also reveal familiarity with photography, which began to flourish in Japan beginning in the mid-1860s.

The artist himself—an autodidact with the most eclectic of imaginable trainings—never made any precise statement about his art. Over the course of his career, he was staggeringly prolific in many genres, from established woodblock techniques to still lives, animal representations, physiognomies (optical anatomies), newspaper cartoons, and a large corpus of war prints. The last of these emerged in a flood of detailed and euphoric depictions of Japan’s emergence as an imperialist power at the turn of the century, when the nation defeated first China, and then Russia, in the Sino-Japanese (1894–95) and Russo-Japanese (1904–5) wars.

While the ninety-three views of Tokyo that Kiyochika produced between 1876 and 1881 remain his main claim to artistic fame in Japan, his oeuvre as a whole reflects an instinctive awareness that depiction of the novel and ambiguous was best communicated by a hybrid medium. Things that look familiar until closer examination reveal hints of the new. Kiyochika applied technical tricks that amounted to approximations of oil painting, copperplate printing, and photography. It seems clear that the collaboration he maintained with the publisher Matsuki Heikichi was committed to producing something more subtle than simply the novelty of depicting new things. The two men seemed committed to finding a different visual language to communicate this newness.

Kiyochika’s 1877 woodblock print titled “Cat and Lantern,” for example, is a macabre tour de force that shows a short-tailed, belled cat attempting to extract a rat trapped in a tipped and burning lantern. Placed in a competition, this was initially misread as an oil painting. Here as in many of his printed works, Kiyochika dispensed with the omnipresent outline of the keyblock print and emphasized (still using multiple printing blocks) undelineated blends of color that replicated oil pigment brushed on a canvas.

|

|

| |

“Cat with Lantern” Kobayashi Kiyochika Woodblock print, ca. 1880

[s2003_8_1151] |

|

|

| |

Kiyochika was also capable of bringing a print to near photographic realism. His 1878 study of the statesman Ōkubo Toshimichi (1830-78), who was assassinated that same year, is modeled after a photograph dating from around 1870. The “engraving” qualities of the print reflect skills being acquired at the time by a number of Japanese artists under the tutelage of Western artists contracted by the Japanese government to produce currency images.

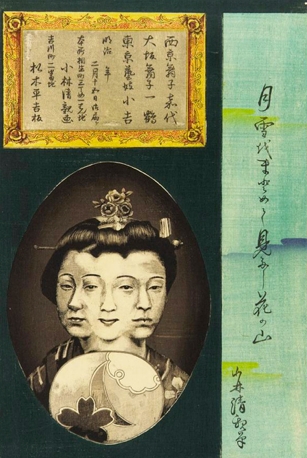

Kiyochika applied this photograph-like sense to traditional subjects as well, as seen in his depiction (also from around 1878) of a triumvirate of geisha beauties representing Kyoto, Osaka, and Tokyo—the traditional Edo-era urban meccas of courtesan culture. The choice of black-and-white, oval framing typical of portrait photography, subtle “roughing” in background areas to simulate an engraving effect, and odd arrangement of faces suggesting a photographic multiple exposure—Kiyochika plotted all this with his publisher Matsuki to introduce a subtle foreign accent to time-honored methods of woodblock-print production.

|

|

|

|

“Portrait Of Okubo Toshimichi”

Kobayashi Kiyochika

Woodblock print, ca. 1878

[s2003_8_1158]

|

|

“Three geisha: Kayo of Kyoto, Hitotsuru of Osaka, and Kokichi of Tokyo”

Kobayashi Kiyochika

Woodblock print, ca. 1878

[s2003_8_1157]

|

|

| |

The Western influence on Kiyochika’s unfinished Famous Places of Tokyo is less pronounced, and lies primarily in wedding techniques of light, shadow, and perspective to the traditional format and production procedures of the woodblock print. In contrast to the ebullience of fellow printmakers who celebrated the influx of Western technology, architecture, and fashions, Kiyochika’s cityscapes commonly evoke images of a vanished, or vanishing, city. They tend to convey a modern sense not of progress, but rather of alienation and loss.

Decades later, in the 1910s, distinguished writers and cultural critics like Nagai Kafū (1879-1959) and Kinoshita Mokutarō (1885-1945) rediscovered this artwork by the young Kiyochika and called attention to the ambiance of loss. Kinoshita referred to the prints as images of the “Old Tokyo.” Nagai Kafū regarded them as peerless documents that, as they were transferred from watercolors into woodblock prints, introduced an element of poetic realism that resurrected a lost city that essentially disappeared after the 1880s.

The distinctiveness of Kiyochika’s melancholy reading of the city can be highlighted by juxtaposing his treatments against renderings of the same or similar locales by his great predecessor, Hiroshige. Take, for example, Kiyochika’s depiction of Mt. Fuji as seen from the city. The hallowed mountain—located some sixty miles southwest of the capital—occupies the background of no less than sixteen of Hiroshige’s views of Edo. In Kiyochika’s series, on the other hand, Fuji makes but a single appearance—still stately and imposing, but presiding over a suburb that is passing through twilight toward darkness. Houselights illuminate the scene. Shadow figures walk the street. An almost silhouetted pine tree occupies the right side of the print (similar to the composition of one of Hiroshige’s renderings of Mt. Fuji); and only close scrutiny reveals something in the scene that did not exist in Hiroshige’s time: a faint line of telegraph wires. |

|

|

| |

Kiyochika’s rendering of the signature Mt. Fuji image features a pine tree that echoes the composition of one of Hiroshige’s renderings of Mt. Fuji (far right). Close scrutiny reveals something in the scene that did not exist in Hiroshige’s time—a faint line of telegraph wires.

Above: Mount Fuji from Abekawa

Kobayashi Kiyochika

Woodblock print, 1881

[s2003_8_1116]

Right: two views from Hiroshige’s 100 Famous Views of Edo, 1856–1859: numbers 8 and 25.

[s2003_8_1151] |

|

| |

In a similar way, the difference between Kiyochika and fellow print artists who took the new capital city as their subject emerges vividly when we juxtapose their respective treatments of two great features of the “new” Japan: trains and Western architecture. In the typical Meiji Westernization print, the steam locomotive was a colorful and ornate form of transportation that conveyed an almost carnival sense of power and progress. Kiyochika dispensed with such flashiness. His singular rendering of the locomotive (possibly based on a Currier and Ives print) depicts a warm, well-lighted train crossing a trestle in near darkness. Natural and man-made light, enhanced by the train’s reflection in the water, invite the viewer to think not just about the train itself, but also about how this changes the way we think of light.

|

|

|

|

“View of Takanawa Ushimachi under a Shrouded Moon”

Kobayashi Kiyochika, woodblock print, 1879

[s2003_8_1179]

|

|

| |

In his rendering of Shimbashi Station, one of Tokyo’s earliest railway terminals and a familiar subject among print artists depicting Western-style architecture, Kiyochika similarly adopted a characteristically different perspective—again moody and nocturnal. We are shown the station not only in nighttime, but also during a rainstorm. A crowd in the foreground, including rickshaw, carries oil-coated paper umbrellas and lighted lanterns; the light emanating from the station is replicated in lines of lantern light reflected on the wet pavement. |

|

|

| |

Kiyochika’s nighttime rendering of Tokyo’s earliest railway terminal, Shimbashi Station, is a moody evocation in which light is reflected in the rain-soaked streets.

Above: “Shinbashi Station”

Kobayashi Kiyochika

woodblock print, 1881

[s2003_8_1199]

Right: “Shinbashi Station”

Utagawa Hiroshige lll

woodblock print

late-19th century

[s2003_8_147] |

|

| |

Of the ninety-three views of Tokyo Kiyochika published before abandoning the series in 1881, twenty-five are nightscapes of one sort or another. It is here that his distinctive preoccupation with light, and his fascination with shadows and the myriad faces of the night, emerge most arrestingly. Human figures, even crowds, are often silhouetted and at once together and alone—observers rather than actors in an oddly quiet landscape. Between dusk and dawn, Kiyochika’s subjects, animate and inanimate, drift through moody shades of gray and blue interspersed with fireworks, moonlight, gaslight, and fireflies.

|

|

| |

Kiyochika’s series includes these rare “night and day” views of the gateway to Toshogu Shrine, Ueno, depicted from exactly the same position. Characteristically, a sense of loneliness pervades both renderings. |

|

|

“View of Ueno's Toshogu in Snow” Kobayashi Kiyochika

woodblock print, 1879

[s2003_8_1148]

|

|

“Toshogu in Ueno at Night”

Kobayashi Kiyochika

woodblock print, 1881

[s2003_8_1149]

|

|

| |

At the same time, however, his depictions of Tokyo by day also usually convey a somber aura—as if the ghosts of the vanished Tokugawa shogunate and disappearing samurai class that had defined the opening decades of Kiyochika’s life were still hovering nearby. There is beauty in these renderings, but joie de vivre is absent. A sense of silence takes its place.

The overarching detachment and melancholy that pervade this new Tokyo by day as well as by night are present in almost every print, and come through even more strongly when the prints are viewed in clusters, or grids, such as the following:

|

|

|

| |

What caused Kiyochika to end his series in 1881, after completing ninety-three views? Clearly, his model was Hiroshige’s 100 Famous Views of Edo. The answer is: fire. Long known as the “flowers of Edo,” fires had consumed large portions of the old feudal capital at regular intervals, and these urban disasters continued into the new Meiji era. In the opening months of 1881, two fires separated by two weeks devastated Tokyo—jumping rivers, razing hundreds of acres, and leaving thousands homeless. Kiyochika’s personal loss in each of these conflagrations was immense. His home, his studio, and his birthplace were all destroyed.

Obliteration, absence, the vanishing of old Japan in the face of foreign intrusions had imbued his Famous Places of Tokyo series with its nagging sense of fragility and uncertainty. Now, abruptly, obliteration had descended in the form of natural disaster. Kiyochika left no written record of his despair on this occasion, but the last four prints he produced before abandoning the project depicted the two fires and their desolate aftermath.

|

|

|

|

|

“Great Fire in Ryogoku Drawn

from Hamacho”

Kobayashi Kiyochika

woodblock print, 1879

[s2003_8_1227]

|

|

“Ryogoku After the Fire”

Kobayashi Kiyochika

woodblock print, 1881

[s2003_8_1223] |

|

|