| |

Souvenir Albums

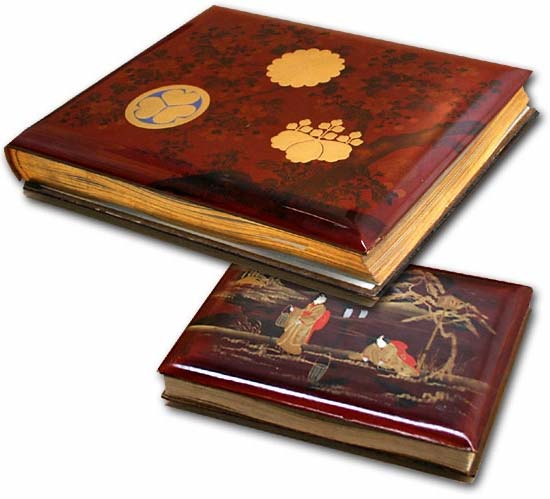

As commercial photography became increasingly central to the tourist trade, photo shops offered a variety of elegant albums in which customers could preserve the images they had purchased. Lacquer album covers became the norm. They were available in two sizes with larger formats measuring roughly 12 x 16 inches and smaller formats being approximately 5 x 7 inches.

|

Albums with lacquer covers were available in two sizes.

Private collections [gj97271] |

Most albums contained 50 photographs but surviving examples have as few as twenty while others hold as many as 80 images.

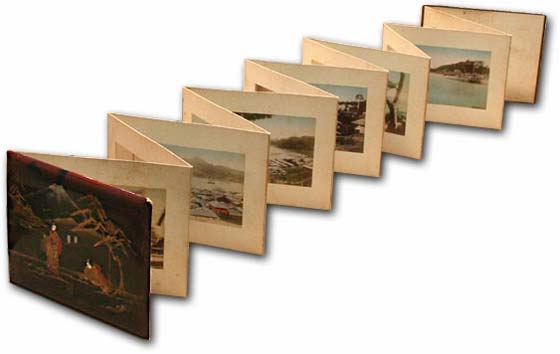

Albums were sometimes bound Western style along the left side, but Japanese-style orihon binding was far more common.

|

Cover designs were quite varied, although exoticism seems to be the prevailing sensibility underscoring the vast majority of examples. Mythological subjects and auspicious symbols were sometimes used as cover images. Floral motifs could stand alone as designs unto themselves, particularly if they had seasonal or symbolic associations, but they were also used as decorative patterns surrounding or backing more pictorial motifs. Album cover designs often evoke the quintessential experiences of globetrotter travel in Japan. Images of Mt. Fuji are extremely common because it was often the first sight travelers encountered as they entered Japanese waters. Jinrikisha and palanquin (kago) images were especially popular motifs on lacquer covers. Globetrotters touring Japan often used these two traditional modes of transport. When featured on album covers, jinrikisha and palanquins functioned as symbols of both travel in Japan and the personal experiences of the globetrotter who compiled the album.

“Same But Different” “Same But Different”

Exoticism was the prevailing tone in album cover designs, with familiar motifs including gnarled pines, figures in traditional Japanese costume, and mountain ranges usually dominated by the wonderfully symmetric Mt. Fuji. These two handmade lacquer covers offer variations on the same scene, and include inlaid ivory for the faces of the women. |

|

Top album courtesy of the author; bottom album courtesy

of the Rauner Library, Dartmouth College

[97297a] [97297b]

|

|

Mythological subjects and auspicious symbols were sometimes also used as cover images. Floral motifs could stand alone as designs unto themselves, particularly if they had seasonal or symbolic associations, but they were also used as decorative patterns surrounding or backing more pictorial motifs. Prominent family crests adorn the top album. Mythological subjects and auspicious symbols were sometimes also used as cover images. Floral motifs could stand alone as designs unto themselves, particularly if they had seasonal or symbolic associations, but they were also used as decorative patterns surrounding or backing more pictorial motifs. Prominent family crests adorn the top album.

Hood Museum of Art [gj97271]

|

The photographs featured in globetrotter albums shared characteristics with—but also differed somewhat from—those produced by Beato in the late 1860s. Black-and-white photographs were widely available but globetrotters generally preferred hand-colored images. As the advertisements cited above indicate, hand coloring was one feature of their product lines commercial photographers most hoped to capitalize on.

“From Black & White to Color” “From Black & White to Color”

While many early photographs are still admired for their “classic” black-and-white qualities, from an early date commercial photographers discovered that tourists were particularly attracted to color. Initially this was done by painstakingly hand-tinting black-and-white prints. By the turn of the century, a revolution in printing processes made possible the mass-production of cheap color picture postcards.

These three images of Hachiman Shrine in Kamakura reflect this evolution. The top is by Felice Beato, dating from the late 1860s. The hand-tinted photo in the middle appeared as a pasted-in illustration in Captain Frank Brinkley’s famous 10-volume series “Japan,” issued in the 1880s. The postcard at the bottom probably dates from the early 20th century. |

|

Hood Museum of Art

[bjh18] [gj10203]

|

The lengthy captions Beato paired with his photographs were unique to his albums. Photographers servicing the globetrotter economy of the 1870s through the 1890s abandoned this practice, with many, but not all, preferring instead to add titles directly on their photographic images. Some commercial firms also included inventory numbers alongside the titles. From the photographers’ perspective, titles and inventory numbers provided the means to manage the large stocks of images they assembled. Most commercial photographers made dozens of images of the most popular sites. Inventory numbers also provided a convenient way to keep track of exactly which view of a popular site their customer had ordered.

|

The lengthy captions Beato paired with his photographs in the 1860s and early 1870s were unique to his albums. Later photographers abandoned this practice, with many preferring instead to add titles directly on their photographic images.

The lengthy captions Beato paired with his photographs in the 1860s and early 1870s were unique to his albums. Later photographers abandoned this practice, with many preferring instead to add titles directly on their photographic images.

The image of the Beato album (above) shows the lengthy caption pasted on the left-hand page. The hand-colored photo below is labeled in the lower left corner.

[gj97261] |

Globetrotter albums were almost always self-selected. Travelers came to the studios seeking images to memorialize their travel through Japan. Although there are exceptions, globetrotters generally retained the views-and-costumes arrangement Beato pioneered. The scenic views they selected were generally organized to represent the one-, two-, or three-day excursions they made from the treaty ports. Typically globetrotter albums follow the tours outlined in popular guidebooks such as those authored by Keeling or Sladen. Albums need not include every excursion, however. It was more common for the customer to choose a sequence of views depicting travel to only his or her most favorite places. We can read these albums as symptomatic of the travel industry in general. Globetrotter tours and the guidebooks that served them tended to pre-package Japan in ways that made travelers’ experiences predictable and therefore profitable. As a result, globetrotter photo albums exhibit shared sensibilities. But because the photographs in any one album were self-selected and arranged by individual customers, globetrotter albums also reveal personal narratives of their owners’ travel and experiences in Japan. These narratives vary according to the class, occupation, gender, and general interests of the individual globetrotters who compiled albums.

Brinkley’s Japan courtesy of Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College

On viewing images of a potentially disturbing nature: click here.

|

|

|

|

|