| |

The Business of Photography

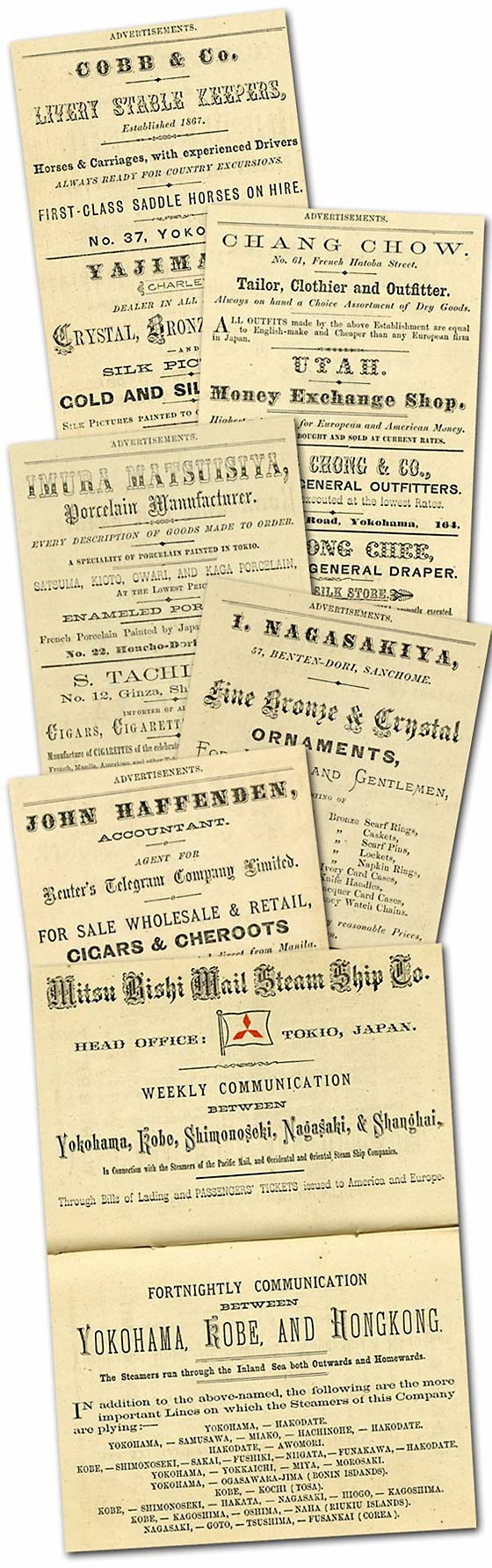

Tourism was a business, of course, and tourist guidebooks such as Keeling’s included many pages of advertisements, mostly placed by merchants in Yokohama. Lacquer, cloisonné, pottery, metalwork, and fabric shops offered the objets d’art most popular among foreign travelers. Ads for hotels, travel companies, and a wide variety of tourist services also appear in many guidebooks.

|

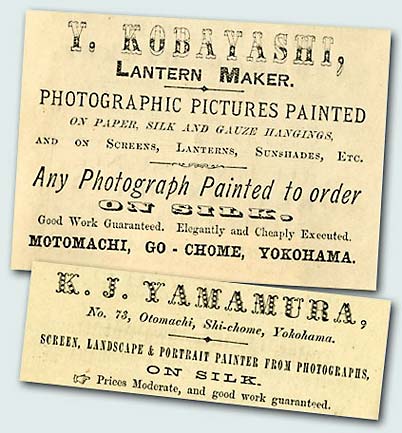

A collage of advertisements from the 1880

Tourists’ Guide by W.E.L. Keeling.

|

Advertisements underwrote the publication costs of globetrotter guidebooks, and as with commercial publications today their number, size, and placement are often indicators of the popularity of a business or service. Of the 43 ads in Keeling’s Tourists’ Guide, 11 promote photography firms. Four of these, moreover, are full-page ads. In other words, advertisements for photography businesses far outnumber those for any other single product in Keeling’s guidebook. Photographs were one of the most popular purchases made by globetrotters visiting Japan. Hand-colored scenes mounted in lacquer-covered albums were recognized around the world as uniquely Japanese symbols of the globetrotter era.

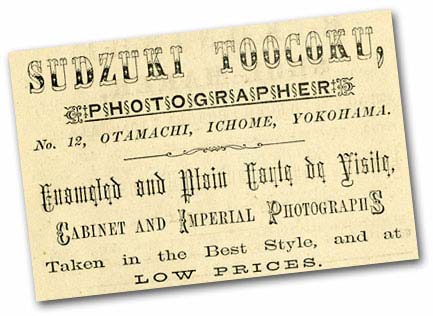

Recent scholarship suggests that hundreds of commercial photographers, both Westerners and Japanese, plied their trade in Japan’s treaty ports and major cities between the opening of the treaty ports in 1859 and the end of the Meiji era in 1912. Advertisements placed by commercial photographers in the 1880 edition of Keeling’s guidebook represent an interesting cross section of the photography business in Yokohama at a time when globetrotter tourism was developing rapidly. Japanese firms offering a wide variety of products and services dominate the smaller advertisements. Suzuki Tōchoku promotes cartes de visite, cabinet, and imperial photographs—formats commonly used by all commercial photographers.

|

W.E.L. Keeling

Tourists’ Guide

[gj30058]

|

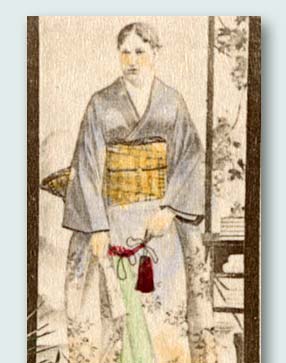

“Photographic Pictures Painted” “Photographic Pictures Painted”

Most globetrotters returned from Japan with albums containing tourist images they had selected from the offerings of commercial photographers in Yokohama and other cities. Some also made a different use of photographs—bringing them to native painters who copied the images on silk, paper, and other materials. These could then be framed, mounted as a hanging scroll (kakemono) or folding screen (byobu), or even displayed on parasols and paper lanterns. |

Advertisements by Y. Kobayashi and K.J. Yamamura in Keeling’s Tourists’ Guide offer such services. Advertisements by Y. Kobayashi and K.J. Yamamura in Keeling’s Tourists’ Guide offer such services.

[gj30061]

[gj30059]

|

|

|

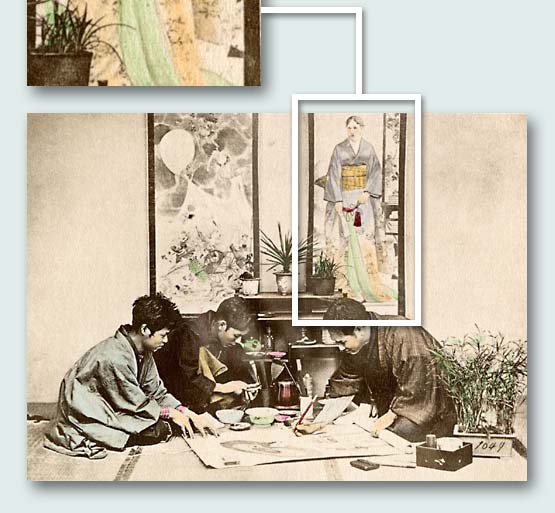

This detail from the photograph "Artist Painting a Portrait" (below)

reveals an example of portrait painting from photographs—in this

case, a Western woman dressed in Japanese kimono—mounted as a

hanging scroll.

[gj20408]

|

|

|

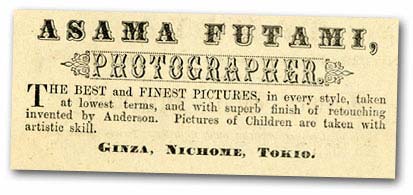

An ad by Asama Fulami promotes his business in the Ginza district of Tokyo, an area frequented by globetrotters visiting the site of the capital.

W.E.L. Keeling

Tourists’ Guide

[gj30058]

|

|

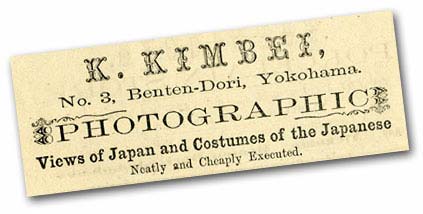

Kusakabei Kimbei, who got his start in photography as an apprentice to Felice Beato, had just opened his first studio when he placed a small ad in Keeling’s guide.

|

W.E.L. Keeling

Tourists’ Guide

[gj30058]

|

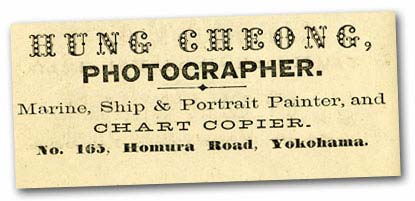

Beato’s influence is evident: Kimbei’s ad promotes views and costumes, two generic categories of images Beato introduced to Japan in the 1860s. Within a few years, Kimbei’s business would expand to the point where he would become one of the leading commercial photographers of 19th- and early-20th-century Japan. Hung Cheong, a Chinese national, worked as a photographer and painter in Yokohama from 1874 to 1885, eventually opening a studio in Hong Kong to take advantage of the globetrotter economy that emerged there.

|

W.E.L. Keeling

Tourists’ Guide

[gj30059]

|

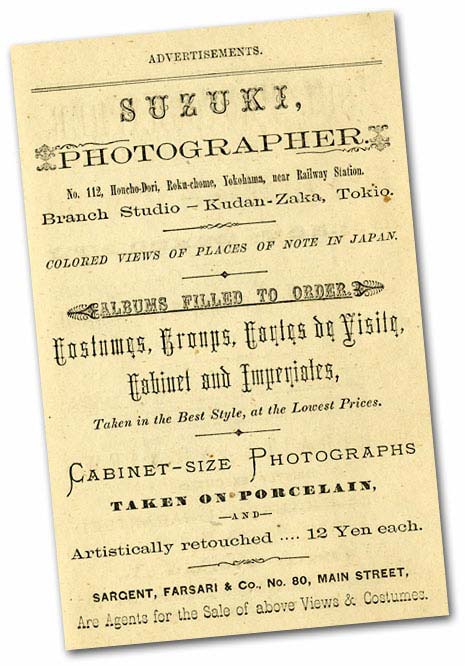

Two Japanese firms purchased full-page ads in Keeling’s guidebook. Suzuki Shinichi opened his business in 1873 after apprenticing with Shimooka Renjō, one of the early Japanese pioneers of photography. But Suzuki’s first introduction to the technology probably came through Beato—he studied Western-style painting with Charles Wirgman, Beato’s business partner. Suzuki would later open a second studio, managed by his son, in Tokyo.

|

W.E.L. Keeling

Tourists’ Guide

[gj30056]

|

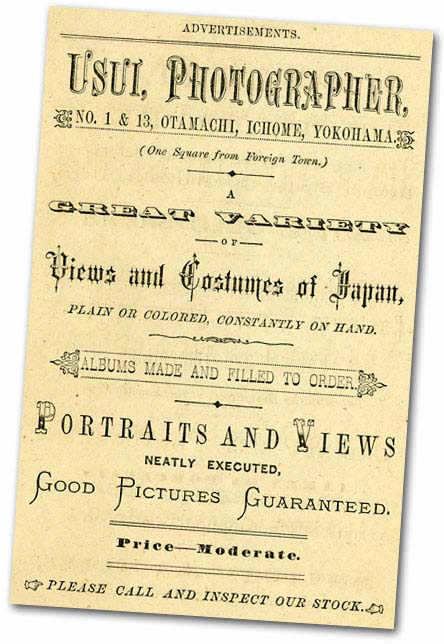

Usui Shuzaburō opened his Yokohama studio in 1880 after training with an American photographer named John Douglas. He was a leading photographer in the port through the mid 1880s.

W.E.L. Keeling

Tourists’ Guide

[gj30056]

|

|

Beato’s precedents are evident in Usui and Suzuki’s advertisements—both promote views and costumes, hand-colored photographs, and albums made and filled to order.

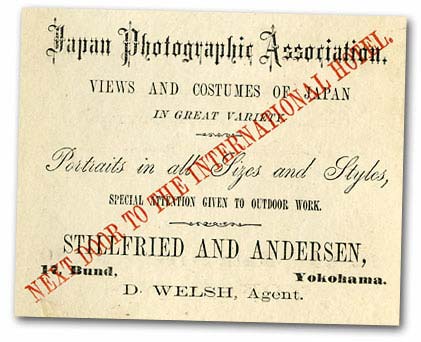

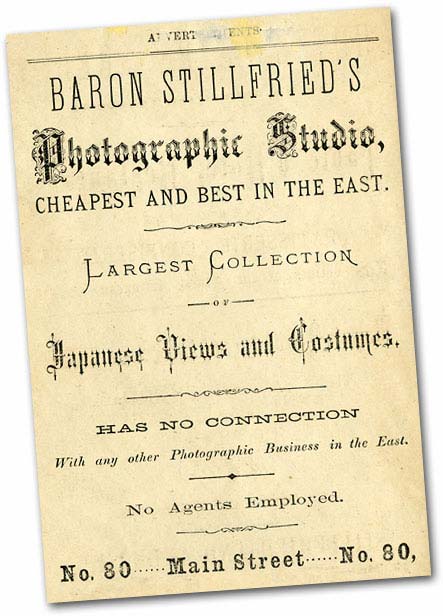

The inside back-cover of Keeling’s guide bears an advertisement from the Japan Photographic Association and lists its proprietors as Stillfried and Anderson. The page opposite bears a full-page ad for Baron Stillfried’s Photographic Studio.

W.E.L. Keeling

Tourists’ Guide

[gj30062]

|

|

|

W.E.L. Keeling

Tourists’ Guide

[gj30062]

|

The Stillfried mentioned in these ads are one and the same person: Baron Raimund von Stillfried, who learned photography from Beato and promptly opened a competing studio in 1871 called Messrs. Stillfied & Co. In 1874 he formed a partnership with Hermann Anderson and renamed his business the Japan Photographic Association. Stillfried and Anderson became Yokohama’s dominant commercial photography firm in 1877 when they purchased Beato’s studio and stock of negatives, but they parted acrimoniously the following year, leading Stillfried to open a new firm simply called Baron Stillfried’s. Anderson continued to operate under the name of their former partnership, which is why Baron Stillfried’s ad prominently states “has no connection with any other photographic business in the East.” In fact, the corporate histories of commercial photography firms are quite complicated. Partnerships dissolved, often in courtrooms. Inventories were divided, sold, and resold—often many times. Negatives made in the 1860s passed through several hands and were still in use in 40 years later.

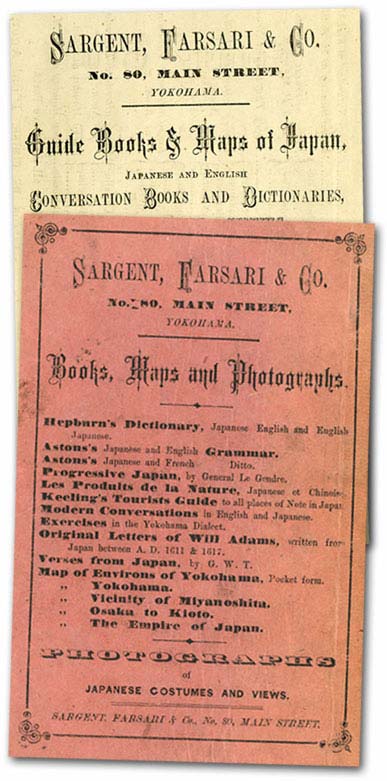

Among the full-page ads, those of Sargent, Farsari & Co. occupy the most prominent positions, opposite the title page and on the back cover. This firm, the sole agent for Keeling’s guide, may also have had a hand in its publication. Sargent, Farsari & Co. sold a variety of printed products (magazines, newspapers, novels, stationary). It also hired out guides for tourists. Adolfo Farsari immigrated to Japan in 1873. At the time he placed ads in Keeling’s guide he was a general merchant brokering photographs made by Suzuki Shinichi (Suzuki’s ad, noted above, mentions this arrangement). In 1885 Farsari purchased the studio and stock of the Japan Photographic Association, formerly owned by Stillfried and Anderson. Within a few years he would parlay his photographic and entrepreneurial skills into one of the most thriving commercial photography firms in Meiji Japan. A. Farsari & Co. survived Farsari’s death in 1898 and was the only foreign-owned firm to continue operations into the 20th century.

W.E.L. Keeling

Tourists’ Guide

[gj30005]

[gj30063]

|

|

The advertisements in Keeling’s guidebook reveal much about the competitive nature of commercial photography in Japan in the early years of the globetrotter boom. The merchant district of Yokohama was not that large, yet it had several studios, many located on the same street or around the corner from their competitors. The Bund and Main Street were the most favorable locations as they were closest to the hotels that accommodated globetrotters. The importance of location is emphasized by the Japan Photographic Association advertisement, which has “next door to the International Hotel” printed in red diagonally over its ad. Each ad in Keeling’s guidebook attempts to draw customers in with tempting language: “largest collection,” “great variety,” “price-moderate,” “best style,” “cheaply executed,” “superb finish,” “lowest terms,” “cheapest and best.” The range of products and services offered by the studios is also an indicator of competition. Each firm advertises a specialization of some kind—cartes de visite, photographs in a number of formats, views and costumes, hand-colored images, albums made to order, and paintings based on photographs to name a few, but none of these products is unique to any one photographer. It is important to note, moreover, that the photographers advertising in Keeling’s guide represent only a small proportion of the commercial studios globetrotters has access to in Yokohama and along the routes they traveled in Japan.

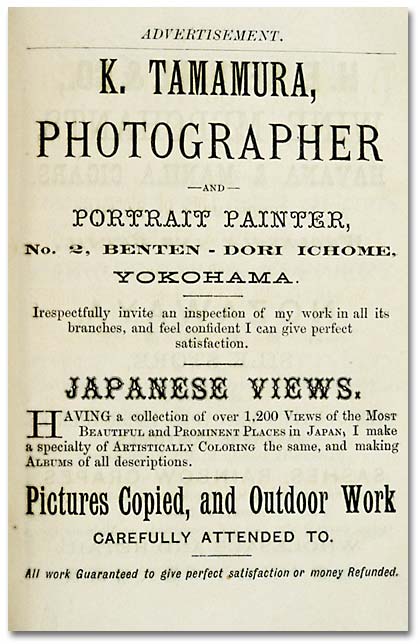

As a point of comparison another guidebook, published a decade after Keeling’s, offers a slightly different view of globetrotter photography in Yokohama. Douglas Sladen’s 1891 Club Hotel Guide: How to Spend a Month in Tokyo and Yokohama has dozens of advertisements for firms clamoring to attract globetrotter business, as does Keeling’s guidebook. There are, however, only three ads for commercial photographers. Farsari and Kimbei, who were just beginning operations when Keeling’s guide was published, bought full-page ads. Tamamura Kozaburō, who established a thriving studio in Tokyo in 1874 but moved his operation to Yokohama in 1883, also had a full-page advertisement. As with Keeling’s 1880 guide, these advertisements do not reflect the great number of commercial photography firms attending to the needs of tourists. There was, in fact, considerable growth in the business in the late 1880s and early 1890s, although Farsari, Kimbei, and Tamamura were certainly the largest and most successful studios.

Ads from Douglas Sladen’s 1891 Club Hotel Guide: How to Spend a Month in Tokyo and Yokohama

(right & below)

[gj98002]

[gj98001]

[gj98000]

|

|

The tone of these later ads reflects a high level of competition. All three firms invite close inspection of their wares and each makes claims to the quality of their products, particularly where coloring is concerned. Albums have a high profile in these ads. Inventories receive special mention, with Tamamura claiming he has 1200 views and Kimbei countering with “over 2000.”

New services have been added. All three firms now have Japanese costumes tourists can wear while being photographed. In addition, the introduction of the Eastman Kodak camera and cartridge film in the mid 1880s prompted Farsari to advertise darkroom and developing services to the generation of amateur photographers these new technologies spawned.

Advertising by commercial photographers in tourist guidebooks affirms the centrality of the medium to the experience of globetrotters. A passage in Sladen’s guide reveals more of their role:“A visit to Farsari’s will be found very entertaining, for one can get no surer index of what is worth seeing in Japan than by looking through Farsari’s cabinets of photographs, which embrace a large portion of the Empire. Tamamura’s photographic establishment should also be visited.

“These establishments will take at least a day to do properly, but once done, the visitor will not only have inspected some of the most important stocks in Japan, but have picked up a variety of information about the country which he could hardly pick up any where else.”

|

Photography shops must have been active social spaces where information and experiences were shared. With the solvency of their businesses dependent on the tourists they served, commercial photographers traveled the popular routes photographing the sites globetrotters found most interesting. In the process they acquired the “variety of information about the country” travelers needed for a successful and pleasant trip. And if Sladen’s guide is to be taken at face value, it seems that globetrotters used photography shops to scope out potential excursions and sites they intended to visit. Commercial studios would realize the benefits of this practice when tourists returned to their shops to purchase souvenir photographs of the places they had visited.

“Old Media and New” “Old Media and New”

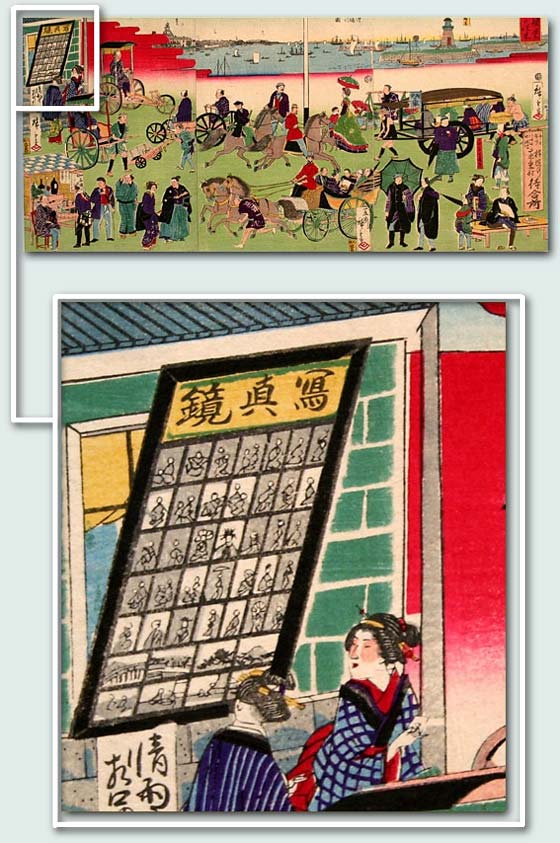

Even as photographs became increasingly popular in Japan, woodblock prints continued to be a major medium for depicting current events—including the many aspects of “Westernization.” |

|

This late-19th-century triptych includes an engaging portrayal of a photography studio with a display of images for sale. This late-19th-century triptych includes an engaging portrayal of a photography studio with a display of images for sale.

Utagawa Hiroshige III (1843-1894)

“Prosperity of Tokyo, Fashion of the Street (Tokyo han’ei hayari no orai)”

Hood Museum of Art[gj30062]

|

Brinkley’s Japan courtesy of Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College

On viewing images of a potentially disturbing nature: click here.

|

|

|

|

|