|

Guidebooks and travel itineraries also drew attention to these subjects, but globetrotters’ urban experience was defined by much more than architectural infrastructure. There is a natural tendency among travelers of any epoch to draw comparisons between their lives at home and what they encounter during their sojourns. From this perspective, even something as commonplace as a grocery store can become an exciting adventure for travelers.

|

|

Shops photographed on the streets. Shops photographed on the streets.

[gj20412] [gj21101] |

As they moved through urban environments en route to a historic building or scenic park, globetrotters encountered an array of interesting scenes. When added to an album, photographs of these street-level encounters would fill out and enliven the record of their urban experiences.

Like tourists today, globetrotters shopped for souvenirs, preferably products and curios unique to Japan. Japan’s official participation in world exhibitions held in Europe and America during the late 1800s ensured that Japanese lacquerware, metalwork, and pottery were recognized the world over for their craftsmanship. Discerning collectors sought high-quality examples and rare antiques from exclusive dealers but most globetrotters bought from stores they happened upon during their daily excursions.

Because price and portability were always concerns for globetrotters visiting many foreign destinations, kimono, paper lanterns, fans, and umbrellas proved to be popular purchases. Photographs of shops featuring these items, many of them reconstructed in studios, appear regularly in tourist albums.

|

| |

Although these appear at first glance to be photos of authentic shops, Although these appear at first glance to be photos of authentic shops,

both are products of the studio.

“Dry Goods Shop” [gj20302]

“Fan Shop” [gj 20105] |

|

Details reveal that the same man, woman, and child served as models. Details reveal that the same man, woman, and child served as models. |

|

|

Interest in popular crafts was such that commercial photographers even staged their manufacture. Models in their employ posed as if they possessed the skills to create these products.

|

|

Globetrotters did not insist on thoroughgoing authenticity in photos of the Japanese at work. Even Brinkley’s expensive “deluxe” volumes did not bother to crop those portions of pasted-in images of people at work that revealed the studio setting. What mattered in photographs such as these was simply showing various traditional handicrafts. Globetrotters did not insist on thoroughgoing authenticity in photos of the Japanese at work. Even Brinkley’s expensive “deluxe” volumes did not bother to crop those portions of pasted-in images of people at work that revealed the studio setting. What mattered in photographs such as these was simply showing various traditional handicrafts.

“Umbrella Maker” [gj20310]

“Maker and Repairer of Samisens” [gj20809]

“Cutting Leaf Tobacco” [gj20707] |

|

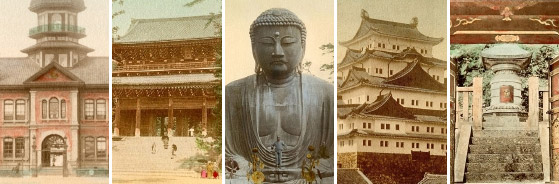

If globetrotter interest in shops and merchants was an extension of their urban experiences, it is perhaps easy to understand their fascination with Japanese religious practice. Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines were commonplace in urban environments—even treaty-port Yokohama—and would have been seen on a daily basis. More significantly, the excursions promoted by guidebooks typically lead globetrotters to historically important centers of religious life. Photographs of Buddhist sites in Kamakura and Kyoto and Shinto architecture at Nikko and Miyajima dominate the scenic views found in most albums. Responding to this interest, commercial photographers offered images of Buddhist monks and Shinto priests posed to highlight the costumes and regalia associated with their vocations. Photographs of religious practices were also popular. Many itinerant Buddhist sects proselytized in cities, and pilgrims were still common on Japan’s highways in the late-19th century.

|

|

Commercial photographers offered images of Buddhist monks and Shinto priests posed to highlight their costumes and regalia.

“Buddhist Monk”

[gj20103]

“Shinto Priest”

[gj20803] |

|

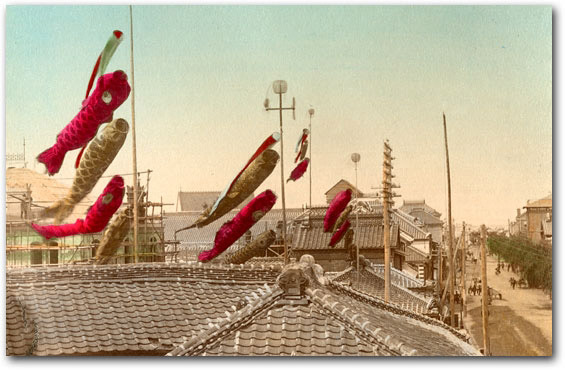

Secular as well as religious festivals constitute another type of imagery globetrotters found attractive.

|

|

This captivating photograph of paper carp flown for the Boys’ Day Festival gives a rare bird’s-eye view of a Japanese town. This captivating photograph of paper carp flown for the Boys’ Day Festival gives a rare bird’s-eye view of a Japanese town.

“Paper Fish for Boys’ Festival”

[gj20211] |

|

Christian missionaries, globetrotters of a different sort, sometimes collected photographs of Japanese religious practices as useful evidence of Japanese heathenism when soliciting financial support from their American congregations.

While ships carried globetrotters across oceans and rail across continents, indigenous forms of transport such as jinrikisha and kago (palanquins) came to represent the experience of travel in Japan. Although jinrikisha were a comparatively recent invention introduced by the foreigners themselves in the 1860s, they were in widespread use in urban areas by the time tourists started arriving in great numbers. Vivid descriptions of their first jinrikisha ride quickly became a trope in travel diaries and photographs of jinrikisha were just as common in albums. Kago, a more traditional conveyance in use for several centuries, were still relatively common during the heyday of tourism, especially for travel in mountainous regions. To emphasize this relationship, studio-posed photographs of kago frequently included painted backdrops showing Mt. Fuji. Kago and Mt Fuji imagery were also popular motifs for lacquer album covers. Although both men and women of all ages used kago and jinrikisha, tourist photographs typically featured young women wearing fashionable kimono. From a globetrotters’ perspective, these “dual-use” images could evoke a personal experience with an indigenous means of transport and, at the same time, satisfy an interest in Japanese women and their dress, coiffure, and deportment.

|

|

Studio-posed photographs of kago or palanquins frequently included painted backdrops showing Mt. Fuji (top). Although jinrikisha were a comparatively recent invention introduced by the foreigners themselves in the 1860s, they were in widespread use in urban areas by the time tourists started arriving in great numbers (bottom). Once again, these purportedly outdoor scenes were taken in a studio. Studio-posed photographs of kago or palanquins frequently included painted backdrops showing Mt. Fuji (top). Although jinrikisha were a comparatively recent invention introduced by the foreigners themselves in the 1860s, they were in widespread use in urban areas by the time tourists started arriving in great numbers (bottom). Once again, these purportedly outdoor scenes were taken in a studio.

“Kago Bearers” [gj20709]

“Jinrikisha Carrying Two Japanese Ladies” [gj20110]

|

Excursions outside major urban centers to Nikkō, Kamakura, or the Mt. Fuji region brought travellers into contact with rural life and customs, making photographs of agricultural production popular keepsakes. Kimbei’s inventory, for example, lists 24 images featuring silk, tea, and rice production. Responding to market demand, some commercial photographers meticulously documented the planting, harvesting, and processing of these products, each of which appealed to globetrotters for specific reasons. Brinkley’s Japan also did this.

Demand for high-quality silk in Europe and America rose dramatically with the opening of Japan to foreign trade in the Meiji era, and the Japanese government promoted silk and silk products as one of the nation’s premier export products. Globetrotter interest in sericulture was linked to these developments. Fascination with Japanese fashion, particularly women’s kimono, also predisposed some travelers to collect images of silk production. Eliza Scidmore, the quintessential American globetrotter who wrote enthusiastically of her visits to kimono shops, devoted an entire chapter to the silk industry in her 1891 Jinrikisha Days in Japan.

|

|

The upper photograph of spinning silk is part of a series that documents the actual production process. The image of spinning below (in this case, cotton) has a different purpose: to show a young lady in an engaging attitude. The upper photograph of spinning silk is part of a series that documents the actual production process. The image of spinning below (in this case, cotton) has a different purpose: to show a young lady in an engaging attitude.

“Spinning Silk from the Cocoons” [gj20914]

“Girl Spinning Cotton” [gj20206]

|

|

The relentless quest for tea provides an interesting sub-narrative to British imperialism in Asia outside Japan. Foreign investment in tea plantations in the Darjeeling highlands was a cornerstone of economic development in India during the 1800s. The opening of China in the 1850s added a repertoire of new teas for export back to Britain. As Japanese teas likewise found new markets with the opening of the treaty ports in the 1860s, commercial photographers filled out their inventories with a range of tea-related images.

|

|

A detail from “Tea Pickers.” The full group photo of women and children conveys a diversity and authenticity that studio portraits could not rival. A detail from “Tea Pickers.” The full group photo of women and children conveys a diversity and authenticity that studio portraits could not rival.

“Tea Pickers”

[gj20611] |

|

Travellers confronted Japan’s tea culture firsthand in every aspect of their travels. Teahouses were popular rest stops along tourist routes, but even wayside kiosks, travelers’ inns, and Yokohama shops greeted guests with a cup of tea.

By the 1880s and ’90s, the heyday of the globetrotter era that saw the publication of Brinkley’s 10-volume opus, most travelers to Japan would have heard of the tea ceremony and welcomed the opportunity to see it performed even by amateurs with no training in the art.

Travel in Asia was a culinary adventure for most globetrotters and Japan was no exception. Guidebooks frequently gave advice about foods that Westerners would find palatable. Published diaries often recommended canned goods from Yokohama suppliers, particularly of beef and coffee, for outings to more remote areas (because Japanese consumed little meat and drank tea). Less adventurous travelers could always retreat to the safety of the Western menus offered in treaty-port hotels.

|

|

“Girl Eating Sushi” features a hodgepodge of items exotic to foreigners: “Girl Eating Sushi” features a hodgepodge of items exotic to foreigners:

tea implements, chopsticks, a plate of sushi, and a musical score and

samisen (a stringed instrument).

“Girl Eating Sushi”

[gj20508] |

Photographs of rice cultivation need to be understood in this context. That Japan’s national diet and, for that matter, its entire economy could revolve around a single agricultural product seemed quaintly archaic to foreigners from industrialized countries. Photographs showing the preparation and eating of rice were a natural extension of those that documented its production.They also afforded insights into eating practices, particularly those employing dishes and utensils unique to Japan.

|

|

Photographs of rice catered to foreign fascination that Japan’s national diet and entire economy could revolve around a single agricultural product. The scene in the center depicts rice being washed at a well prior to cooking. Photographs of rice catered to foreign fascination that Japan’s national diet and entire economy could revolve around a single agricultural product. The scene in the center depicts rice being washed at a well prior to cooking.

“Cultivating Rice Field” [gj20202]

“Washing Rice” [gj20613]

“Family Supper” [gj20902] |

|

Brinkley’s Japan courtesy of Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College

On viewing images of a potentially disturbing nature: click here.

|

|

|