| |

Representation & Misrepresentation

Images of individuals and small groups of Japanese, mainstays of the genre of photographs referred to in the world of commercial photography as “costumes,” were acquired in two ways. Photographers attuned to the patterns of globetrotter travel ventured out along popular routes photographing human activities their clientele would encounter. These in situ images showing Japanese engaged in the affairs of everyday life were photographed in homes, shops, markets, and along streets and highways.

|

|

Contrasting methods of photographing vendors: a staged studio shot (left) and a “snapshot” taken on the street (right).

[gj20409] [gj20704]

|

Profitable studios also employed models, whom they outfitted with garments and accouterments highlighting gender, age, class, and occupational differences. These studio-posed images constitute the vast majority of the “costumes” sold by commercial photographers.

|

|

A closer look at the studio shot reveals the edges of the background screen and scattered rocks. A closer look at the studio shot reveals the edges of the background screen and scattered rocks. |

Photographs of shopkeepers in busy markets, farmers working their fields, tradesmen on job sites, and craftsmen plying their skills convey a snapshot sensibility but, in truth, the slow exposure times of late-19th-century cameras meant that photographers had to pose their subjects in order to acquire saleable images.

|

|

“Itinerant Merchant” has an impressive sharpness of detail. While outdoor shots may have been more natural than studio shots, the long exposure time still required subjects to pose for a long while. “Itinerant Merchant” has an impressive sharpness of detail. While outdoor shots may have been more natural than studio shots, the long exposure time still required subjects to pose for a long while. |

|

|

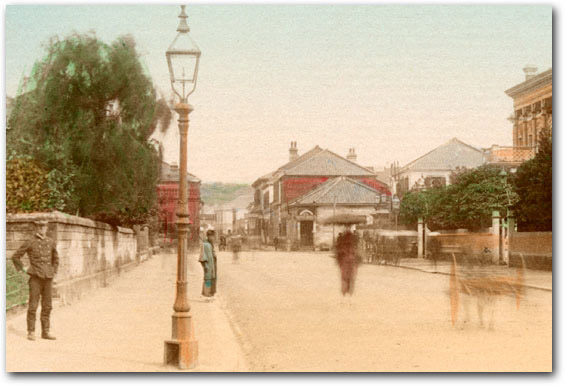

In this photograph of Main Street, Yokohama, the long exposure time resulted in ghost-like apparitions of a moving jinrikisha and figure with an umbrella amidst more stationary figures in Western and native dress. In this photograph of Main Street, Yokohama, the long exposure time resulted in ghost-like apparitions of a moving jinrikisha and figure with an umbrella amidst more stationary figures in Western and native dress.

“Main Street, Yokohama”

[gj10811] |

Studios provided a much more controllable environment. Many studio-posed photographs thus adopt the conventions of portraiture with the subject seated or standing against a neutral backdrop. These images focus viewers’ attention on details of coiffure and costume, which were often highlighted with hand coloring.

|

|

“Tokyo Beauty” (left) is a delicately hand-colored photograph from Brinkley’s Japan. A different woman appears in the identical pose and setting in

Kasumasa Ogawa’s book Celebrated Geysha of Tokyo, published around 1892. Ogawa used the identical studio setting for many of his geisha portraits. Although the photos in Brinkley’s 10-volume opus came from a number of well-known Japanese photographers, no attributions are given.

“Tokyo Beauty”

[gj20301]

|

|

|

The studio environment, however, could also appear stark. To liven up their images, commercial photographers often utilized props and painted backdrops to suggest architectural interiors or outdoor settings. These artificial environments were especially necessary when photographing occupations and activities that required an appropriate temporal or spatial context. The need to stage most of their images invested commercial photographers with an inordinate amount of authority to determine how Japanese people would be presented to a foreign audience. Misrepresentation was not only possible but also probable given these modes of production.

|

|

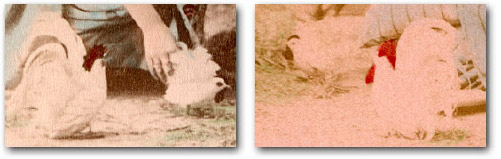

Two photos titled “Feeding Chickens” appear in Brinkley’s Japan. Two photos titled “Feeding Chickens” appear in Brinkley’s Japan.

The painted backdrop and hand-tinting differ, but this highly artificial motif appears to have specific guidelines as to the poses of the women.

[gj20807] [gj21004] |

|

The appearance of an identical rooster and chick in the two photos reveals their artificial nature. The appearance of an identical rooster and chick in the two photos reveals their artificial nature. |

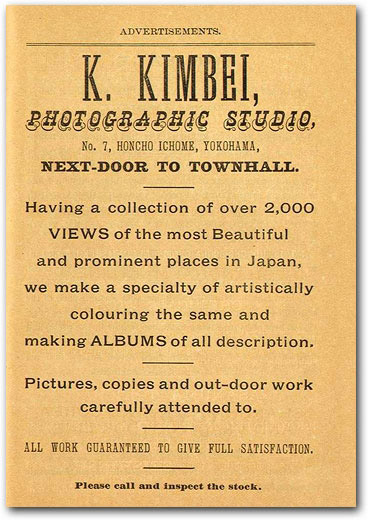

Other studio practices furthered the possibility of misrepresentation. Following protocols established in the 1860s by Felice Beato, the pioneer of Japanese photography, commercial studios organized their inventories into two broad categories: scenic views and costumes. Kimbei’s 1893 pricelist exemplifies this practice. The 1,700 scenic views in his inventory were organized according to the routes and destinations most favored by globetrotters. The remaining 400 photographs depicted Japanese people. Unlike his scenic views, this portion of Kimbei’s list conveys no organizational scheme and appears to have been compiled in an ad hoc and additive manner.

|

Kusakabe Kimbei’s 1893 ad touts “over 2,000 VIEWS,” artistic coloring and “making ALBUMS of all description.”

1,700 scenic views in his inventory were organized according to the routes and destinations most favored by globetrotters. The remaining 400 photographs depicted Japanese people.

|  |

|

The arrangement of inventories into views and costumes was replicated in most extant globetrotter albums. Views typically appear first and are usually arranged to reflect the itineraries of individual consumers. “Costumes” follow, often in disproportionately fewer numbers, indicating scenic views were the primary means by which globetrotters memorialized their travels. Among the latter, in situ scenes and studio-posed images were randomly mixed together, suggesting no effort on the part of travelers to distinguish between the two or to question the artificiality of photographs staged in a studio. For globetrotters, the subjects themselves were compelling; the means by which they were photographed mattered little.

The scenes-and-people dichotomy had the effect of extracting Japanese from their broader cultural environment, particularly with studio-posed images. Then, when reunited in albums, new relationships emerged. We assume that globetrotters chose photographs of Japanese people that approximated what they actually saw, but other considerations may have played a role.

Commercial photographers often stocked images that would have been nearly impossible for globetrotters to witness first hand. Although the samurai class that had governed Japan for many centuries was legislated out of existence in the early 1870s, for example, studio-posed photographs of models dressed in full battle armor or enacting harakiri appear regularly in globetrotter albums.

|

|

Although the samurai class that had governed Japan for many centuries was legislated out of existence in the early 1870s, studio-posed photographs of models dressed in full battle armor or enacting harakiri—as in this image titled “An Actor”—appear regularly in globetrotter albums.

“An Actor”

[gj20805]

zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz

|

|

|

The separation of views and “costumes” thus becomes more than just an organizational trope. Monumental architectural structures and scenic natural wonders could not be staged and possessed, therefore, the capacity to authenticate globetrotters’ experiences in Japan. Within the context of an album, these scenic views lent their authenticity to the “costumes”—even to posed images that globetrotters’ were unlikely to have seen during their travels. This transference of authenticity facilitated the construction and perpetuation of stereotypes.

Kimbei’s pricelist provides a unique and illuminating glimpse of the array of choices globetrotters confronted when choosing “costumes” for their photo albums. Using the titles he applied to his photographs, it is possible to organize his inventory into broad thematic categories. Typologies are never perfect—some of Kimbei’s titles convey little about what is actually depicted and some images could be assigned to more than one thematic category. Nonetheless, his inventory indicates which photographic subjects globetrotters found most interesting. About 30 percent of Kimbei’s depictions of native Japanese focus on work broadly defined. This includes shopkeepers, itinerant vendors, tradesmen, craftsmen, farmers, and transportation workers such as coolies, jinrikisha pullers, and kago bearers.

|

Great care was taken in hand coloring this “Tattooed Postman.” This method of mail delivery had all but died out by the time globetrotters began arriving in great numbers, but—like samurai and other feudal images—enjoyed iconic status in studio-posed photographs. Where tourist photography focused on “work,” this usually meant shopkeepers, itinerant vendors, tradesmen, craftsmen, farmers, and transportation workers such as coolies, jinrikisha pullers, and kago bearers.

Workers in the less picturesque emerging sectors of the economy such as textiles and heavy industry had no place in the tourist’s view of Japan.

“Tattooed Postman”

[gj20610]

zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz

|

|

|

|

Images of religious life and customs, comprised mostly of Shinto priests, Buddhist monks, pilgrims, and a variety of rites and festivals, represent about 6 percent of the total.

|

|

This studio-staged photograph of a “pilgrim” is typical of popular religious subjects. Just as tourist photos of occupations tended to exclude factory work in the emerging industries, portraits of “the Japanese” collected by globetrotters rarely included the wearing of fashionable Western-style attire. The touchstone was almost always “the traditional.”

“Pilgrim”

[gj20405]

zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz zzzzzzzz

|

|

|

Most photographs depicting occupations and religious life feature men, but the overall gender balance of Kimbei’s inventory (roughly 65 percent) favors women. Photographs of women cover a wide range of professional, domestic, and personal activities. 3 percent of Kimbei’s images depict samurai. Miscellaneous subjects rounding out the list include exotica such as Ainu and tattoos, as well as more specialized occupations such as sumo wrestlers, doctors, and masseuses. Kimbei also had three photographs of Koreans and one image of Chinese (!) beheading criminals.

It is important to bear in mind that the preferences for certain types of images—as revealed in Kimbei’s inventory—were determined primarily by his market. Commercial photographers made their living capitalizing on the predilections and proclivities of their clientele. The task, then, is to understand why globetrotters were drawn to the subjects and themes that dominate Kimbei’s inventory.

|

Brinkley’s Japan courtesy of Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College

On viewing images of a potentially disturbing nature: click here.

|

|

|

|

|