| |

DIPLOMACY

"Do you think the Empress is sincere in her profession of friendship?” I asked.

"If you could meet her and she should take your hand and look in your eye and speak to you as she has to me, you would think her sincere," was the answer.

"A man's first impression of a woman as deep as the Empress is not worth much," I said.

"I would rather trust a woman's intuition of the woman.”

“What does that tell you?"

"I cannot think otherwise than that she is sincere.“

—A conversation with Sarah Pike Conger

from Friendly China (1949) by Bailey Willis [9]

The first years of the 20th century following the Boxer Uprising of 1900 saw an unprecedented level of diplomatic engagement by the Qing Court, as the necessity to cast off traditions of imperial seclusion became apparent. Moreover, there was an apparent realization that establishing personal ties between the Empress Dowager and the Beijing diplomatic community was necessary for constructive international relationships. In a bold step, Cixi hosted a series of gatherings at the palace for the ladies of the legations, assuming that the women would be more amenable to appeals of friendship.

|

|

|

| |

A party of Westerners invited to the palace after the Boxer Uprising. Cixi took particular interest in hosting visits by ladies from the foreign legations.

detail [cx236] |

|

| |

Cixi’s graciousness at these functions was duly reported to the press, making a generally positive impact on her international reputation. Cixi developed a particularly strong friendship with Sarah Pike Conger, the wife of the American envoy to Beijing. Conger wrote movingly of Cixi’s many virtues in newspaper articles and books. The image of Cixi holding the hand of Conger, tightly surrounded by other ladies of the American legation, reveals the lengths to which Cixi was willing to go to forge personal bonds.

|

|

| |

Cixi holds the hand of Sarah Pike Conger, the wife of the American minister to Beijing. Three other ladies of the American legation make up the group, along with the young daughter of the photographer Xunling.

[cx113] full and detail

|

|

|

| |

Photos for the White House

Research of diplomatic documents surrounding the photographs has turned up a 1904 memo from Sarah Conger’s husband, Minister

to

Peking

Edwin

Conger, to Secretary of State John Hay, describing a large photographic portrait of the Empress Dowager and requesting that it be presented to President Theodore Roosevelt:

The portrait was received at the Legation in a black wood box, lined with yellow silk, with a yellow silk curtain hanging over the front of the picture inside the box. The box was encased in a well-fitted, yellow quilted silk case; and over all was spread an exquisitely embroidered cloth of imperial yellow. [10]

After an exhaustive search by the Freer Gallery, the photograph was discovered in the attic of Blair House, the State Department’s official guest residence for visiting heads of state. The portrait is currently in a State Department frame, the original box and brocades unfortunately lost. In spite of age darkening, the surface is lavishly tinted, with dense, minute details picked out in brilliant gold paint. The effect is one of regal authority, while the scale of the figure and her direct gaze lend a sense of personal affinity—perhaps just the combination Cixi believed would be most effective in communicating with a fellow head of state.

|

|

|

|

The Empress Dowager sent this large and lavishly tinted photographic portrait to President Theodore Roosevelt in 1904. It was only recently rediscovered.

[cx207]

|

|

|

| |

The painted and gilded print sent to President Roosevelt is typical for its time. In the early age of photographic enlargements, technical limitations impaired the quality of rescaled prints, with considerable loss of detail, clarity, and tonal range. Yet while image deterioration was generally unavoidable, in this instance it was used to advantage.

Careful study of the underlying print with the applied colors digitally removed reveals a near complete loss of detail and shading, leaving only a faint outline of facial features. Painted details are strategically applied to redefine key features, including the chin and lower jaw outline, thereby creating a compelling illusion of youthfulness. The Blair House portrait masterfully uses the new technology of photography to convey the presumption of realistic accuracy, yet with the artistic license of painted portraiture.

|

|

|

This Xunling photographic print of Cixi in the Palace Museum in Beijing was the source for the colorized version sent to President Roosevelt. This Xunling photographic print of Cixi in the Palace Museum in Beijing was the source for the colorized version sent to President Roosevelt.

Palace Museum, Beijing [cx243] |

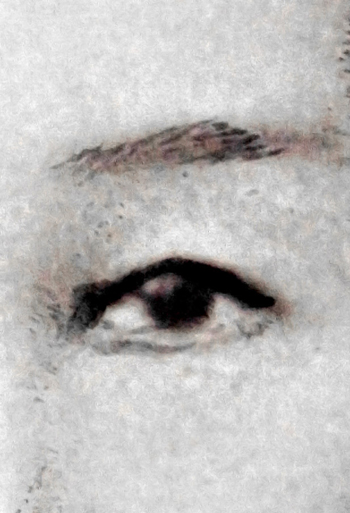

Close-up detail of Cixi's left eye in the portrait given to Theodore Roosevelt shows fine

details

created

with

the

brush. Close-up detail of Cixi's left eye in the portrait given to Theodore Roosevelt shows fine

details

created

with

the

brush.

[cx210] |

|

| |

The manipulated Cixi portrait reveals more than the desire to glamorize a 70-year-old ruler. After 1900, indemnities demanded by the foreign

powers for losses incurred in the Boxer Uprising were crippling the Chinese economy and undermining support for the Qing government. Since the Americans were regarded as more disposed to relinquish their portion of the indemnities, it was Roosevelt (and his family) who were the target of gifts personally bestowed by the Empress Dowager. Indeed, an argument can be made that the portraits were part of a strategic calculation to develop interpersonal ties to effect diplomatic objectives.

In such ways, the Xunling photographs were part of a larger effort to maintain political legitimacy and relevance by an increasingly enfeebled and desperate Qing court. It is a striking coincidence that indemnity reductions called for by Roosevelt were passed by Congress in 1908, the same year as Cixi’s death. Were the photographs, then, the whim of an insular and erratic ruler, or a calculated element in a carefully managed foreign policy initiative?

In addition to the Blair House portrait, Roosevelt’s daughter Alice (1884–1980) received a smaller portrait when she visited Beijing in 1905. Alice had achieved a degree of celebrity both for her entertainingly rebellious public behavior and her good looks. Naturally, the newspapers made much of this symbolic clash of civilizations. As The Washington Times quipped, “It well may be that the visit of this young American girl will have its effect on the terrible old woman who rules China, and that it will help along the improvement of the great empire.” [11]

|

|

|

| |

Alice Roosevelt, daughter of President Theodore

Roosevelt, photographed in China in 1905.

detail [cx205]

|

|

| |

This graphic juxtaposition of Alice Roosevelt and the Empress Dowager

appeared in The Washington Times, September 14, 1905.

[cx204]

|

|

| |

The audience of the president's daughter with Cixi took place at the New Summer Palace in mid September. In her autobiography, Alice writes that on the day after the audience:

A troop of cavalry clattered down the street to the Legations, surrounding an imperial yellow chair in which, by itself, was the photograph. It was in an ordinary occidental gilt frame, but the box that held it was lined and wrapped in imperial yellow brocade and the two officials were of much higher rank than those who brought the Pekinese [a dog also received as an imperial gift]. [12]

This vivid description suggests that rather than a mere personal memento, the photograph has become an extension of the imperial presence, due the ceremony and deference given the Empress Dowager herself. Like the portrait sent to her father a year earlier, the photograph Alice received had been carefully reworked to make Cixi appear decades younger.

|

|

|

| |

Close-up detail of the portrait Cixi presented to Alice Roosevelt reveals the lengths

taken

to

create

an

unblemished

appearance. Every effort is made to create an agreeable image of China’s leader.

detail [cx202]

|

|

| |

Western Paintings of the Empress Dowager

I was obliged to follow, in every detail, centuries-old conventions. There could be no shadows and very little perspective, and everything must be painted in such full light as to lose all relief and picturesque effect. When I saw I must represent Her Majesty in such a conventional way as to make her unusually attractive personality banal, I was no longer filled with the ardent enthusiasm for my work with which I had begun it, and I had many a heartache and much inward rebellion before I settled on the inevitable.

—Katharine Carl, With the Empress Dowager of China (1905)

In addition to Xunling's suite of photographs, two Western portrait painters made influential contributions to the refurbishing of Cixi's image in the United States. One was the American Katharine Carl, who became an admirer and close acquaintance of the Empress Dowager, and quickly became famous for writing and lecturing about her. The other was the Dutch-American artist Herbert Vos, one of whose portraits eventually came to reside in Harvard University's Fogg Art Museum. |

|

|

| |

top: two portraits of Cixi by Katharine Carl, 1903–1904

bottom: portraits of Cixi by Hubert Vos, 1905

details

[cx212] [cx302]

[cx303] [cx317]

|

|

| |

In 1903 Sarah Conger, the wife of the American envoy to Beijing, approached Cixi regarding the commissioning of a large oil painting, to be displayed at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair “in order that the American people may form some idea of what a beautiful lady the Empress Dowager of China is." The commission was carried out by Katharine Augusta Carl (1865–1938), who took up residence in the New Summer Palace between September 1903 and August 1904.

|

|

Katharine Carl in Chinese dress, in an image from her 1905 book With the Empress Dowager of China. Katharine Carl in Chinese dress, in an image from her 1905 book With the Empress Dowager of China.

detail [cx310] |

|

| |

In her memoirs about this rare experience, Carl describes persistent pressure by both court officials and Cixi herself to conform to traditional standards of portraiture:

As the portrait progressed I found myself constantly running up against Chinese conventionalities as to the way it was done. They wished so much detail and no shadow.…no fantasy could be indulged in painting the portrait of a Celestial Majesty. It was necessary to conform to rigid conventions. [4]

Carl also wrote that on the 19th of April, with the painting near completion, a reception was held for foreign guests and imperial princes. The painting was temporarily placed in its carved wood frame, and:

…a young Manchu, who had been attached to a Legation abroad and had learned photography in an amateur way, had been ordered by Her Majesty to make a photograph of the portrait. This was done while the Princes and nobles were still in the court. When it was photographed, and the Princes had retired, the scaffolding was again put up, the picture was raised out of this carved wood pedestal and was replaced in my studio. All this took the greater part of the day.

|

|

| |

The American artist Katharine Carl, invited to produce a painting of Cixi for the 1904 Louisiana Purchase

Exposition, spent many months living in the imperial court precincts in Beijing to carry out this unprecedented commission. The flattering, life-size portrait above (112

x

64

inches [284.5

x

162.6

cm]) produced by Carl

was placed

in

a

massive

frame

said

to

have

been

designed

by

Cixi, shipped to St. Louis accompanied by a large retinue of Manchu officials, and given a prominent place in the exposition's art gallery.

|

|

|

above: Carl's painting being shipped to St. Louis, with above: Carl's painting being shipped to St. Louis, with

Manchu officials lined

up on the right.

[cx240]

left: The portrait in

its wooden frame.

[cx239]

below: The portrait on

display at the exposition.

[cx241] |

| |

After the exposition closed, the portrait of Cixi was presented to President Theodore Roosevelt by the Chinese ambassador in a ceremony at the White House, and subsequently transferred to the Smithsonian Institution. Katharine Carl, for her part, coupled publication of her 1906 book With the Empress Dowager of China with an extensive book tour. All of these choreographed activities were designed to establish Carl's flattering portrait as the public face of imperial China's “great lady” in the United States.

|

|

|