|

|

Between 1884 and 1898, Chinese readers were treated to a revolutionary publishing undertaking aimed at a mass audience: the Dianshizhai huabao—literally “Illustrated News of the Dianshizhai Lithographic Studio,” and more concisely rendered as “Dianshizhai Pictorial.” Published three times a month in Shanghai, imperial China’s most cosmopolitan metropolis, this periodical offered more than just a graphic window on contemporary Western as well as Chinese happenings and developments. In its format, illustrations, and textual commentary, the Daishizhai Pictorial was itself a dramatic example of what was deemed both new and/or newsworthy in the closing decades of the Qing dynasty.

Image-driven commentary by Rebecca Nedostup and Jeffrey Wasserstrom follows here in Part 1. Part 2 complements this with a full set of images from the first six issues, including Chinese texts and English translations.

Part 3 provides access to over 1000 black-and-white illustrations that appeared in the pictorial over the course of its decade-and-a-half run. These

were generously digitized at the request of MIT Visualizing Cultures by the Sterling Memorial Library at Yale University.

For anyone interested in late-Qing society and culture as Chinese of the time literally depicted and viewed it, the Daishizhai Pictorial can be seen as a fascinating counterpart to such famous Anglophone weeklies as England’s Illustrated London News (1842–2003) and, in the United States, Harper’s Weekly Journal of Civilization (1857–1916) and Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper (1855–1891).

|

|

|

The images in this unit unless otherwise noted are illustrations from the 1898 edition of the Dianshizhai huabao, generously provided by the Sterling Memorial Library at Yale University.

|

|

|

| |

PICTURE WINDOWS

Rebecca Nedostup

Introduction

When a reader delved into an issue of the Dianshizhai huabao (The Illustrated News of the Dianshizhai Lithograph Studio, or as we will call it Dianshizhai Pictorial, or simply Dianshizhai), he or she was not merely gazing into a window onto the enormous cultural and technological changes visible in the periodical’s home, the treaty port of Shanghai. In fact, he held in his hand the physical manifestation of this new world, a publication that did not just depict novelties in “China” and “the West” but in its very way of showing and seeing argued for a different way of approaching the times.

The novelty that the Dianshizhai offered was a combination of lithographic illustration and on-site reporting (or the illusion of such), which together packed a potent one-two punch of detailed verisimilitude and high drama. Eventually, the power and authority of the illustrations even superseded that of the original news items on which they were based, and the textual descriptions that accompanied them (authored separately from the hand of the artist). Like many of the American and European illustrated newspapers that served as the Dianshizhai’s early inspiration, the periodical was born in a serendipitous mixture of commerce and exploitation of a public’s hunger for wartime news (in this case, that of the 1884–1885 Sino-French War).

It flourished, however, feeding an appetite for renderings and explanations of the influx of new technologies and customs from outside China, as well as the equally bewildering domestic shifts in mores, politics, and customs. Similarly, though early issues contained copies of illustrations from publications such as Harper’s Weekly or The Illustrated London News, the house style most frequently melded the kind of technical renderings that lithography allowed with illustrative flourishes adopted from woodblock prints, ink painting, and other older techniques in which the stable of artists were trained. Such skills only heightened the dramatic effects for the viewer (which, in deference to the visual as well as verbal primacy of these documents, is how we will refer to the Dianshizhai audience).

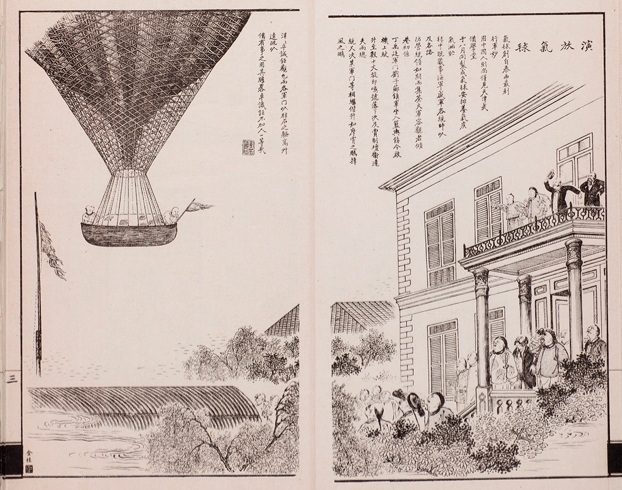

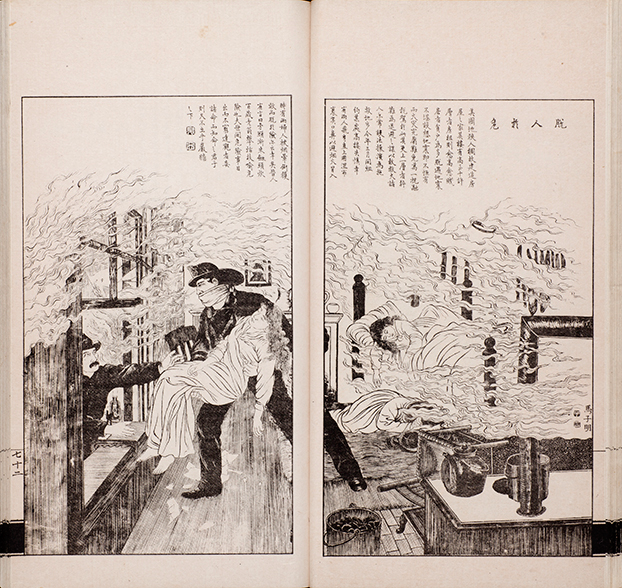

The piece “Escape from Danger,” from the first year of the Dianshizhai’s 14-year run (1884 to 1898), offers a striking example of the marriage of foreign subject matter, new technology, and local artistic sensibility in the service of high drama. Offering a commentary on urban crowding, predatory landlords, and tenement conditions as the context for disaster, the text relates how nonetheless the advanced equipment of New York City firefighters allowed them to “fly” to the rescue of women overcome in a burning high-rise.

|

|

|

| |

To depict the swirling smoke, artist Ma Ziming draws on the undulating “clouds” most often seen in Chinese religious sculpture, bas-reliefs, and prints, heightening the emotion and atmosphere of a scene already full of the frisson of male firefighters pulling prone, unconscious young women from their bedroom. Yet he also uses the delicacy of lithography to show in fine detail the stove, coal bucket, and kettle—not to mention the unfamiliar aspects of the firemen’s uniform and grooming. To depict the swirling smoke, artist Ma Ziming draws on the undulating “clouds” most often seen in Chinese religious sculpture, bas-reliefs, and prints, heightening the emotion and atmosphere of a scene already full of the frisson of male firefighters pulling prone, unconscious young women from their bedroom. Yet he also uses the delicacy of lithography to show in fine detail the stove, coal bucket, and kettle—not to mention the unfamiliar aspects of the firemen’s uniform and grooming.

|

| | |

“Escape from Danger” 脱人於危

1884 jia (Vol. 2, p. 23)

artist Ma Ziming

[View caption & English translation]

Yale 2.024 [dz_v02_024]

|

|

| |

Dianshizhai Print Shop

from Shenjiang shengjing tu,

(Shanghai: Shenbaoguan,

1884)

Image courtesy Yale University

[Dianshizhai_Print_Shop]

|

|

| |

The Dianshizhai Pictorial was merely one leg of a communications strategy embraced by the media entrepreneur of 19th-century Shanghai, an expat Londoner named Ernest Major (1841-1908). In his mid-century ventures in China, Major made the early and canny move from trade to industrial investment, which led him to found the seminal Chinese-language newspaper Shenbao in 1872. From that base he hired Chinese lithographers to create the Dianshizhai Studio in 1878, generating from the technology a tremendously successful series of books, art reproductions, and albums of local sights. [1]

The appetite for rapid-response visual depictions of current events near and far was already strong, and Major and the Chinese editors he hired, such as Cai Erkang, experimented with ways to meet the demand. The Shenbao house distributed copper-engraved world maps, photographic prints, and a short-lived supplement that used woodblock technology to copy scenes from the English illustrated press; these competed in a marketplace alongside woodblock-print depictions of battle scenes and court paintings, illustrated novels, handbooks, ritual manuals, and devotional texts. [2]

Lithography offered to enhance the number of prints that could be made and circulated—100,000 prints could be made from a lithographic plate, as opposed to 25,000 from a high-quality woodblock—but perhaps more crucially, also the type of information that they could convey. On May 8, 1884, Major launched his illustrated newspaper with a direct argument that the lithograph was the proper instrument for comprehending the times, including rapidly-moving and technologically-significant events such as the Sino-French War being fought in Vietnam:Western drawing is different from Chinese. Those accomplished in the drawing of events in the Western method [with copper engravings] will make efforts to get a close likeness. Nearly all of them will furthermore use an acid for highlighting, and even in details as fine as finest hair and with a multitude of different layers [in the perspective], they still do not lack small empty spaces [between the lines]. With a magnifying glass one can fully appreciate their achievements in terms of space and depth.

—Ernest Major, Founding Statement for Inaugural Issue of Dianshizhai Pictorial, May 1884, translated by Rudolf G. Wagner, “Joining the Global Imaginaire,” p. 133.

Major openly remarked on the public’s appetite for news images of the war in Vietnam:

People who wish to do something good draw pictures about victories in this war, and they are bought and looked at in market places, and quite easily become props for conversation… I have therefore asked people with fine skill for drawing events to pick sensational and entertaining scenes and make illustrations of them. [3]

|

|

|

|

|

|

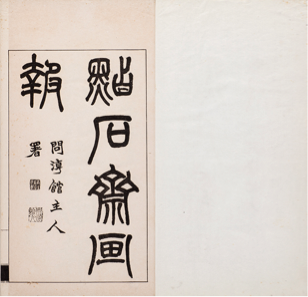

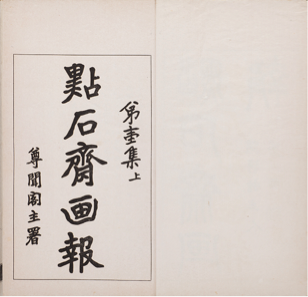

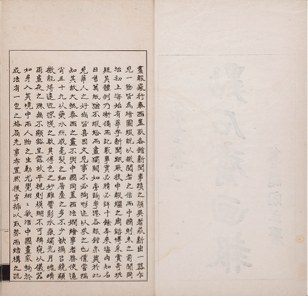

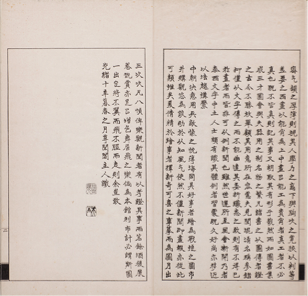

First four pages of inaugural issue of

Dianshizhai Pictorial, May 1884.

lower row: Major’s founding statement, signed by the

“Master of the Pavilion of Respecting the News”

(Zunwenge)

[View text & English translation]

right: detail of title page

[dz_v01_001] [dz_v01_002]

[dz_v01_003] [dz_v01_004]

|

|

| |

Just as in today’s media world, however, that Major sensed an opportunity to feed desires for the “sensational and strange” did not mean that he, his artists, and his editors embraced either wholesale Westernization or a revolutionary shift in visual and verbal vocabularies. Rather, the Dianshizhai Pictorial should be seen as a vehicle for melding new ways of rendering scenes and information into a local context.

Just as in today’s media world, however, that Major sensed an opportunity to feed desires for the “sensational and strange” did not mean that he, his artists, and his editors embraced either wholesale Westernization or a revolutionary shift in visual and verbal vocabularies. Rather, the Dianshizhai Pictorial should be seen as a vehicle for melding new ways of rendering scenes and information into a local context.

Wagner notes how careful Major is always to refer to Chinese textual tradition, such as the long history of illustrated collecteana he cites in his founding statement. He commissioned editor Shen Yugui (1808-1898) to write the magazine’s title in a seal script in vogue among literati of the time.

Furthermore, Major softened the radicalness of the periodical’s content by presenting it in a format that resembled a book more familiar to a scholar of the day. Each page was folded over, and eight pages bound in an issue, along with additional material including advertisements, supplements, and reproduced paintings glued in as inserts. [4] Most illustrations (with their accompanying text) took up one page, though one page of each issue would bear two half-page drawings. Occasionally a magnificent illustration would stretch across two pages. Three issues a month were produced, totaling 528 by the time the Dianshizhai ceased publication on August 16, 1898.

Neither was the Dianshizhai exactly a periodical in the sense of a general-interest magazine that would regularly appear in someone’s mailbox. Bound sets of issues and reprints began to appear almost immediately, and the publisher encouraged viewers to give these as gifts. Very soon, then, as Wagner points out, the illustrations began to be detached from their moorings in the “what/when/who/where/how” of “news,” and began to take on independent lives in the visual realm.

Reproduction & Innovation

In the pages of the Dianshizhai the reader could discover a microcosm of the multiple technologies and moral-cultural systems of the late Qing world. This sometimes extended to the visual styles mixing in the very illustrations themselves. Historian of print culture Cynthia Brokaw points out that lithographic products continued to be but one option available to consumers through the end of the Qing, along with woodblock books and other kinds of publications. Looking at the Dianshizhai, one can see that even the Chinese lithograph itself changed tremendously in a short period.

|

|

| |

“American Consul Arrives at Han[kou]”

&

“White Elephant of Siam”

|

|

| |

These facing pages reveal the roots of the Dianshizhai. On the righthand page, the remains of Ernest Major’s first efforts to pass on pictorial news of the world to Shanghai consumers, when he would simply commission reproduction of images (in this case photographs) of visual goodies from overseas publications too tempting to pass up.

|

|

| |

Here a page containing two photographs is reproduced directly from the American Harper’s Weekly (detail at right). The details of a Thai elephant’s appearance in New York are rendered in Chinese for the reader, along with florid descriptions of the animal himself. The men of Lieutenant Greely’s ill-fated polar expedition get no verbal explanation, however, but simply hang on as a ghostly presence in the middle of the page.

Here a page containing two photographs is reproduced directly from the American Harper’s Weekly (detail at right). The details of a Thai elephant’s appearance in New York are rendered in Chinese for the reader, along with florid descriptions of the animal himself. The men of Lieutenant Greely’s ill-fated polar expedition get no verbal explanation, however, but simply hang on as a ghostly presence in the middle of the page.

On the lefthand page of the spread, meanwhile, readers found an illustration in a much more conventional style of a more standard political event—the greeting by Qing officials of an arriving foreign consul (detail below). This was done by Wu Youru, a painter and illustrator who had become especially known for his genre drawings depicting women in domestic and leisure settings, and who would produce around a third of Dianshizhai’s visual output during its first four years of existence.

Here his style is not much different from that of woodblock prints and paintings depicting official and court doings already in circulation—except that we catch a faint glimpse of the faintly comical variation in facial expression and individual demeanor among the arrayed ranks of bureaucrats and policemen that the lithograph afforded, and that would become the hallmark of Dianshizhai artists.

|

|

|

| |

Soon, however, Wu was reproducing neither drawings and photographs from abroad nor prints from his local environment, but along with his fellow artists was creating a third style that was wholly their own. Rather than use the lithographic technology to reproduce and disseminate another new form of representing reality, such as the photograph, the Dianshizhai artists deployed it to heighten the drama and detail of a panoramic medium that was already in their wheelhouse—the woodblock print.

|

|

| |

So in drawing the 1884 Colchester earthquake Wu Youru uses the new medium on the one hand to depict the literally granular detail of the crumbling buildings, and their dazzling European architectural design—something that city dwellers may have seen the likes of, but may have still been in the imaginations of many countrymen (see detail below).

|

|

| |

Like the American Civil War battlefield artists who produced drawings that ended up as prints in Leslie’s Weekly (for examples, see “The Becker Collection/Drawings of the American Civil War Era”), Wu Youru often sketched news on the spot.

Like the American Civil War battlefield artists who produced drawings that ended up as prints in Leslie’s Weekly (for examples, see “The Becker Collection/Drawings of the American Civil War Era”), Wu Youru often sketched news on the spot.

Here, though, he was forced to draw from his mental image bank and technical proficiency and so the distant melds with the local in the shape of an English church tower crashing onto a Lower-Yangzi-style roof (detail right).

|

|

| |

Yet he also takes care to reveal pathos and fellow suffering of the human beings struck by disaster as seen in the men and child cowering under the trees (detail right).

|

|

| |

Looking at Ships: From Far-Away to Close-at-Home

Wu Youru was instrumental in helping Dianshizhai make its name depicting naval battles of the Sino-French war, a key conflict that tested the Westernized military technology introduced by the “Self-strengthening” (ziqiang) reform movement that followed the Taiping Rebellion. Through his work and that of other artists the portrayal of marine technology and the drama of warfare at sea became something of a house specialty.

The following three images show us how Dianshizhai artists began by depicting for Shanghai viewers a war taking place in relatively distant south China and Southeast Asia, rendering in minute detail both the exciting action of war and the rapidly-shifting military technology that accompanied it. Eventually, they turned the skills they had acquired onto events closer to home, using the same visual flair to generate excitement via the drama of the familiar mixed with the spectacular. Visually evocative, staged views of the news feature ships at war—“Second Attack on Jilong,” and in domestic dramas—“A Steamship Stranded” and “Rescue on Lake Tai."

|

|

| |

“Second Attack on Jilong”

|

|

| |

In the war scene (“Second Attack on Jilong”) the textual account describes the second attack of French forces on the Taiwan port of Jilong (Keelung) in fall 1884, after their first attempt during the summer was repelled. Though the reporter decries the inhumanity of the barrage of cannonfire launched by three ships upon the Qing fortifications, Wu’s illustration rather seems to send another message.

|

|

| |

Eagle-eyed viewers (perhaps armed with magnifying glasses!) could not only follow the trajectory of dozens of cannonballs, they could marvel at every detail of the French steamships’ funnels and rigging, and delight at the gestures and poses of the animated crewmen. This was not the first time a Dianshizhai written text and its accompanying illustration would seem to be at odds, nor would it be the last.

Eagle-eyed viewers (perhaps armed with magnifying glasses!) could not only follow the trajectory of dozens of cannonballs, they could marvel at every detail of the French steamships’ funnels and rigging, and delight at the gestures and poses of the animated crewmen. This was not the first time a Dianshizhai written text and its accompanying illustration would seem to be at odds, nor would it be the last.

We should not conclude that Wu Youru was therefore politically apathetic. This seems to have been more a matter of artistic sensibility and deploying the medium in a way that late Qing literati viewed as natural.

That is to say, there was no shortage of moral exhortation in the Dianshizhai, but it came across most clearly in the writing, which was done in a classical style. Text was still seen as the primary venue for such expressions for the literarily-trained men who by and large made up the Shanghai media world of the time.

|

|

| |

Conveying moral or political ideas solely through a non-textual, visual medium was an argument some decades away from being made in China. Yet Wu and the other Dianshizhai artists—however inadvertently—pushed that latter world into being through their staged views of the news that heavily emphasized some visual elements (and therefore some elements of the story) over others.

|

|

| |

Here again Wu cannot help himself in illustrating the news of a passenger steamship run aground at the port of Wusong; the magnificence of the ship overwhelms the evacuation of the passengers, and calls into being several other steamships to accompany it.

|

|

| |

An image shows the transport of people from the stranded vessel to a rescue ship on the left. Another paddlewheel steamer is also on the scene in the background.

An image shows the transport of people from the stranded vessel to a rescue ship on the left. Another paddlewheel steamer is also on the scene in the background.

|

|

| |

Other artists would find ways to make lithographic marine drama work in the service of the literati ethics and, as Ye Xiaoqing points out, somewhat conservative politics that Dianshizhai writers espoused. Tian Zilin lavishes as much loving care on the local sailing boats of Lake Tai, not far from Shanghai in Jiangsu Province, as Wu Youru did on the new technology of the steamship.

|

|

| |

The boats are whipped by wind and waves as their occupants use ropes and hooks, or dive into the stormy lake, to rescue capsized fishermen.

The boats are whipped by wind and waves as their occupants use ropes and hooks, or dive into the stormy lake, to rescue capsized fishermen.

Ma’s dramatic scene does not undercut the text’s explanation that this rescue happened courtesy of a local civic service, a water rescue in place since the early Guangxu era (ca. 1870s), which distributed cash rewards for people brought back. “Meritorious deeds continue,” the reporter noted approvingly.

|

|

| |

A Notebook for the Shanghai Man

In neither text nor illustration, then, should we understand the Dianshizhai Pictorial to be “objective” news in the way that modern journalism has come to enshrine reporting. Three issues a month—nine illustrations an issue—demanded choice, and Major’s writers and illustrators reflected the very hybrid quality of the audience for which they decided what was “sensational and entertaining.”

These “settlement literati” (Ye Xiaoqing’s term) were by and large trained in the scholar-official system of the Qing, but by choice or happenstance, found themselves operating outside of it in the Shanghai commercial and social world. Far from abandoning their cultural underpinnings, though, they simply applied it to the urban whirlwind around them. Thus their Dianshizhai functions somewhere in between a modern newspaper and an elite gentleman’s biji, a diaristic collection of interesting tidbits along with his own commentary (in that sense, the late Qing illustrated newspaper served many functions that we expect of a blog now).

Stories were meant to excite, shock, and spur innovation, but they were also meant to caution, moralize, and provide an anchor in times of rapid social change. There was no single editorial voice for the Dianshizhai, and writers did not always agree with one another on important political or cultural issues of the day. And as we have already seen and will continue to see throughout this unit, sometimes the text of a story imparts a stern message that is directly contradicted by the intrigue and excitement generated by the image.

The audience, or viewership, is difficult to ascertain with any certainty, because it was common to recirculate issues of this and other publications among many hands. Major rather grandiosely claimed the desire for the pictorial to make its way to the workers of Shanghai, and farmers and tradesmen beyond, but the written style would have limited the reading of the texts to the “middle-brow” educated and above. There is little documentation as yet, however, on the lives of the illustrations themselves, but print culture is a thriving topic among young scholars of China around the world, and perhaps we will soon know.

Although Ernest Major and the Dianshizhai editors took a restrained view of the political upheavals of the time—obliquely commenting on but not supporting, for example, the demands for reform of the dynastic government—the publication could not remain immune to them. In the chaotic environment following the ill-fated Hundred Days of Reform in 1898—a period of aborted moves toward constitutional monarchy, power plays at court, and the jailing or exile of a number of political reformers and radicals—the Dianshizhai ceased publication. Its collective visions continued to circulate and reverberate, however, beyond Shanghai and beyond these 14 influential years.

|

|

| |

|

|

|