| |

WHO IS THE BARBARIAN?

In an 1899 cartoon, René Georges Hermann-Paul attacked the hypocrisy of spreading civilization by force by juxtaposing the words “Barbarie” and “Civilisation” beneath Chinese and French combatants who alternate as victor and victim. When the Chinese man raises his sword, it is labeled “barbarism,” but when the French soldier does precisely the same thing it is “a necessary blow for civilization.”

|

|

| |

“Barbarie — Civilisation”

Full caption: “It's all a matter of perspective. When a Chinese coolie strikes a French soldier the result is a public cry of ‘Barbarity!’ But when a French soldier strikes a coolie, it's a necessary blow for civilization.”

Le Cri de Paris, July 10, 1899

Artist: René Georges Hermann-Paul

[cb54-002_1899_July10_BarbCiv_HermannPaul]

|

|

| |

What did the public back home know about the fighting of these far-off wars? Each of the three major turn-of-the-century wars left a trail of contention in the visual record. In the U.S., pro-imperialist graphics created the image of robotic, unstoppable American soldiers stomping on foreign lands and towering over barefoot savages. Anti-imperialist protesters were often feminized as weak “nervous Nellies” and, in a play on words, as “aunties.” Antiwar graphics, on the other hand, informed the public about the darker side of imperial campaigns.

“Lucky Filipinos”: the Philippine-American War

Life published many graphics that showed the humanitarian costs inflicted by war and political aggression—despoliation, looting, concentration camps, torture, and genocide—often awkwardly interspersed amongst humorous sketches and domestic scenes. The graphics protesting U.S. actions in the Philippines were particularly biting, as seen in a page satirically titled “Lucky Filipinos.” Rising from the flames of a burning home, a skeletal apparition represents the hundreds of thousands of Filipinos killed in the U.S. campaign. Under the American flag, patriotic words end with a question mark:

‘Tis the Star-Spangled Banner, Oh! Long May It Wave.

O’er The Land of the Free and the Home of the Brave?

|

|

|

| |

“Lucky Filipinos.”

Life, May 3, 1900

Artist: unknown

Source: Widener Library, Harvard University

[cb92-315_1900_May3_life1900v2_008_widener]

|

|

| |

The long text accompanying this grim illustration reads as follows:Lucky Filipinos.

It appears that the Filipinos have lost confidence in Americans.

Do those benighted wretches fail to realize what we have accomplished in their islands?

We may have burnt certain villages, destroyed considerable property and incidentally slaughtered a few thousand of their sons and brothers, husbands and fathers, etc., but what did they expect? Were we to transport an army more than half way around the earth merely to listen to peace propositions?

Not much.

And look at Manila.

Two years ago the main street of Manila did not possess a single saloon. Now there are thirteen on this one street!

And they complain that drunken American soldiers insult the native women.

What do they expect from a drunken soldier, anyway?

Progress is now in those islands.

She may be red-handed, and at times drunk, but she is there for business.

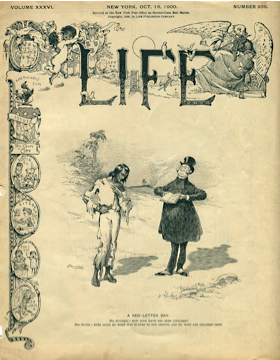

“Scorched earth” tactics destroyed scores of villages. How such uncivilized behavior fit the rhetoric of the civilizing mission is the subject of the Life cartoon, “A Red-Letter Day.” Against a backdrop of distant flames, a Filipino man—sympathetically drawn as tall, handsome, and heroic in contrast to the usual caricature of a tiny, expressionless savage in a grass skirt—is questioned by a clergyman. The caption reads: “The Stranger: How long have you been civilized? The Native: Ever since my home was burned to the ground and my wife and children shot.”

|

|

“A Red-Letter Day.

The Stranger: How long have you been civilized?

The Native: Ever since my home was burned to the ground and my wife and children shot.”

Life, October 18, 1900

Artist: Frederick Thompson Richards

[cb94-319_1900_Oct18_Life]

The dignity of the bereaved Filipino in this cartoon is a stark contrast to the usual demeaning stereotypes of “half devil and half child” that Kipling endorsed and many cartoonists reinforced. In this rendering it is the Bible-toting white invader (“The Stranger”) who is ridiculed. |

|

| |

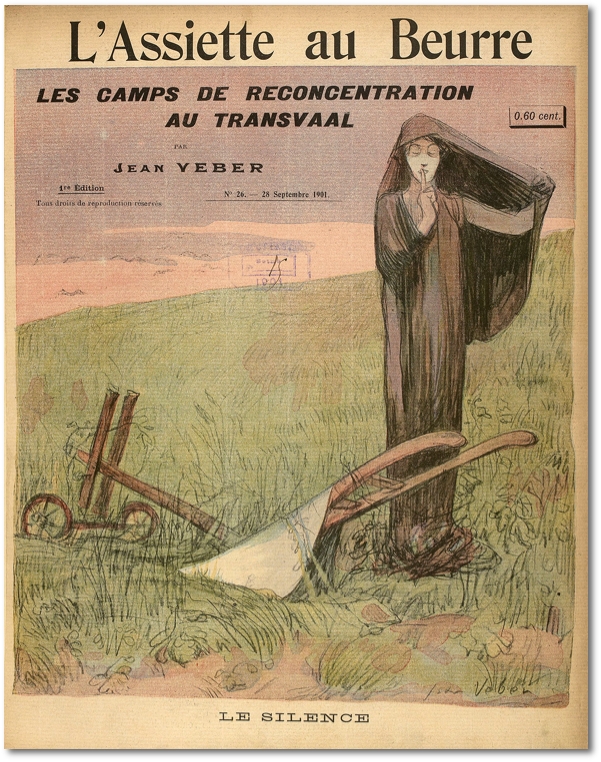

“Le Silence”: the Second Anglo-Boer War

The French leftwing magazine L’Assiette au Beurre (The Butter Plate) had a substantive run from April, 1901 to October, 1912. Dominated by full-page graphics, many issues were thematic visual essays developed by a single artist. In the September 28, 1901 issue, artist Jean Veber excoriated the shameful subject of the concentration camps British forces used to weaken Boer resistance in the Anglo-Boer War of 1899–1902. The strategy was among several emerging in these “small wars” of the turn of the century.

Initially, the camps were conceived as shelters for women and children war refugees. British armies had difficulty stopping mounted Boer commandos spread out over large areas of open terrain. The campaign was stepped up to target the civilian population that provided crucial support for guerrilla fighters in both the Transvaal and Orange Free State republics. Families were burned out of their homes and imprisoned in concentration camps.

Though black Africans did not fight in the war, over 100,000 were rounded up and confined in camps separate from the white internees. All of the hastily organized camps, for whites and blacks alike, had inadequate accommodations, wretched sanitation, and unreliable food supplies, leading to tens of thousands of deaths from disease and starvation. A post-conflict report calculated that close to 28,000 white Boers perished (the vast majority of them children under sixteen), while fatalities among incarcerated native Africans numbered over 14,000 at the very least.

The British people had a long history of supporting imperial wars and as the conflict escalated, criticism in cartoon form declined and was supplanted by patriotic messages. French artists, on the other hand, leveled charges of barbarism against Great Britain and other imperial powers, including their own country, in vivid graphics. Veber’s series, “Les Camps de Reconcentration au Transvaal,” begins with the cover image “Le Silence,” in which a veiled woman holds her finger to her lips, standing over the remnants of what appears to be an electric fence and a plow that suggests the earth has been tilled to bury evidence.

|

|

|

| |

“Les Camps de Reconcentration au Transvaal. Le Silence”

(“Concentration Camps in the Transvaal. Silence”)

L’Assiette au Beurre, September 28, 1901

Artist: Jean Veber

Source: Bibliothèque nationale de France

[cb60-200_1901_Sept28_Transvaal_pg00]

This special issue of L’Assiette au Beurre drew particular attention to the brutal tactics adopted by the British in the Boer War, including herding the families of the Boer opponent into concentration camps. Stark images such as these helped make public a subject that was generally suppressed.

|

|

| |

In Veber’s rendering of “Les Progrès de la Science” (The Advancement of Science), Boer prisoners of war are being shocked by an electric fence to the amusement of British troops on the other side. The image is ironically paired with a quote attributed to an “Official Report to the War Office” that says ”iron railing through which an electric current runs makes the healthiest and safest fences.”

|

|

|

|

“Les Progrès de la Science”

(The Advances of Science)

L’Assiette au Beurre, September 28, 1901

Artist: Jean Veber

Source: Bibliothèque nationale de France

[cb61-201_1901_Sept28_Transvaal_pg06]

British soldiers laugh at the spectacle of Boer prisoners of war being shocked by an electric fence. The title of the cartoon calls attention to the barbarous uses of much modern technology and so-called “progress.”

|

|

|

Caption: “...les prisonniers boërs ont été réunis en de grands enclos où depuis 18 mois ils trouvent le repos et le calme. Un treillage de fer traversé par un courant électrique est la plus saine et la plus sûre des clôtures. Elle permet aux prisonniers de jouir de la vue du dehors et d’avoir ainsi l’illusion de la liberté... (Rapport officiel au War Office.)” Caption: “...les prisonniers boërs ont été réunis en de grands enclos où depuis 18 mois ils trouvent le repos et le calme. Un treillage de fer traversé par un courant électrique est la plus saine et la plus sûre des clôtures. Elle permet aux prisonniers de jouir de la vue du dehors et d’avoir ainsi l’illusion de la liberté... (Rapport officiel au War Office.)”

|

Translation: “...the Boer prisoners were gathered in large enclosures where, for the last 18 months, they found rest and quiet. An iron railing through which an electric current runs is the healthiest and safest of fences. It allows prisoners to enjoy the view from the outside and have the illusion of freedom ... (Official Report to the War Office.)” Translation: “...the Boer prisoners were gathered in large enclosures where, for the last 18 months, they found rest and quiet. An iron railing through which an electric current runs is the healthiest and safest of fences. It allows prisoners to enjoy the view from the outside and have the illusion of freedom ... (Official Report to the War Office.)” |

|

| |

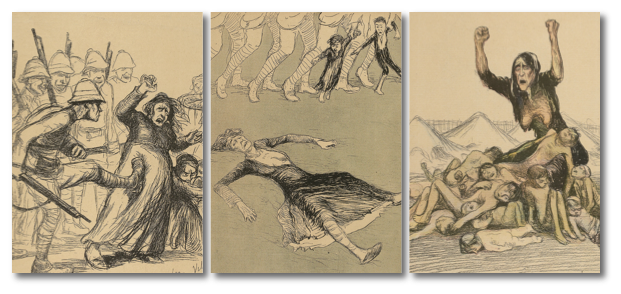

In an image titled, “Vers le Camp de Reconcentration” (To the Concentration Camp), women and children are dragged off by British soldiers. The caption again ironically quotes an “Official Report to the War Office” that praises the British soldiers’ bravery in the face of a fierce enemy, in this case women and children: “The humanity of our soldiers is admirable and does not tire despite the ferocity of Boers.”

|

|

|

|

“Vers le Camp de Reconcentration”

(“To the Concentration Camp”)

L’Assiette au Beurre, September 28, 1901

Artist: Jean Veber

Source: Bibliothèque nationale de France

[cb62-203_1901_Sept28_Transvaal_pg09]

Women and children were included among the Boer prisoners of the British. The French caption mocks British hypocrisy in officially praising the humanitarian behavior of their armed forces.

|

|

|

Caption: “... hier encore nous avons pris un important commando. Je l'ai fait reléguer sous bonne escorte. L'humanité de nos soldats est admirable et ne se lasse pas malgré la férocité des Boërs ... (Rapport officiel au War Office.)” Caption: “... hier encore nous avons pris un important commando. Je l'ai fait reléguer sous bonne escorte. L'humanité de nos soldats est admirable et ne se lasse pas malgré la férocité des Boërs ... (Rapport officiel au War Office.)”

|

Translation: “... yesterday we took important commandos. I relegated an escort. The humanity of our soldiers is admirable and does not tire despite the ferocity of the Boers ... (Official Report to the War Office.)” Translation: “... yesterday we took important commandos. I relegated an escort. The humanity of our soldiers is admirable and does not tire despite the ferocity of the Boers ... (Official Report to the War Office.)” |

|

|

| |

Additional details from Jean Veber’s “Les Camps de Reconcentration au Transvaal” illustrations in the Sept. 28, 1901 issue of L’Assiette au Beurre. Source: Bibliothèque nationale de France

[view complete issue]

|

|

| |

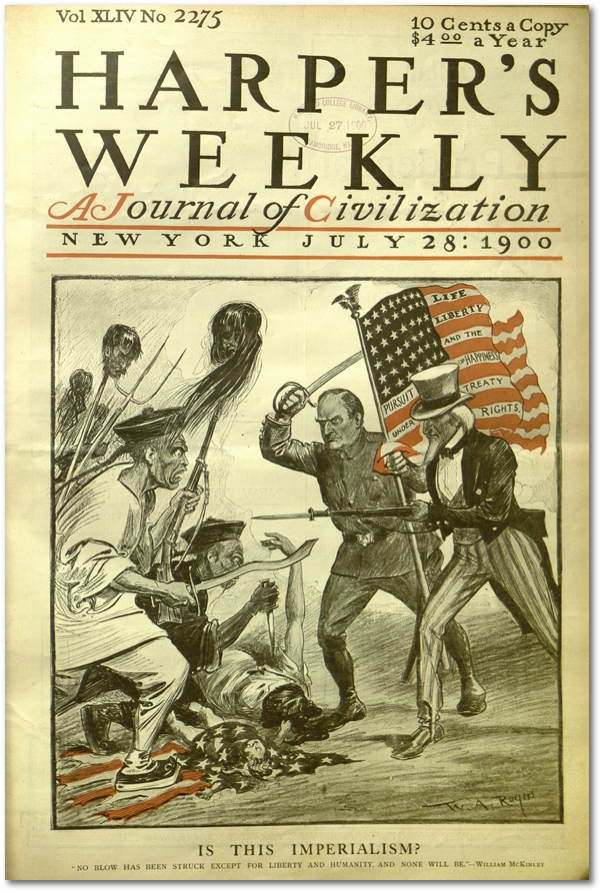

“Is This Imperialism?”: the Boxer Uprising

In the eyes of the West, China was dangerously close to chaos as the new century began. World powers competing for spheres of influence within her borders had grown ever bolder in their demands as the Qing rulers appeared increasingly weak. Western missionaries had penetrated the interior, and the missions they established disrupted village traditions. The influx of cheap Western goods eroded generations-long trading patterns, while telegraph and railroad lines were constructed in violation of superstitions, eliciting deep resentment among Chinese. Some of the poorest provinces in the north were further stressed by a destructive combination of flooding and prolonged drought. There, membership in militant secret societies swelled, most prominently in the Yi He Quan (Society of the Righteous Fist), a sect known to Westerners as the Boxers.

Christian missionaries, their Chinese converts, and eventually all foreigners were blamed for the troubles and attacked by Boxer bands of disenfranchised young men. By the spring of 1900, Boxer attacks were spreading toward the capital city of Beijing. Foreign buildings and churches were torched and the Beijing-Tianjin railway and telegraph lines were dismantled, cutting communication with the capital. A rescue expedition made up of troops from eight nations, under the command of the British Vice-Admiral Edward Seymour, left Tianjin for Beijing. The expedition met with unexpectedly fierce opposition from Boxers and Qing dynasty troops and was forced to retreat. On June 17, while the fate of Seymour and his men remained unknown to the outside world, Allied navies attacked and captured the forts at Taku. In one of the most lasting images of the conflict, the legation quarter in Beijing—overflowing with some 900 foreign diplomats, their families, and soldiers, along with some 2,800 Chinese Christians—was put to siege. On June 21 the Empress Dowager Cixi declared war on the Allied nations.

The Boxer Uprising was a godsend for the righteous exponents of a world divided

between the civilized West and barbaric Others. As the disturbance escalated, so did news coverage around the world. Reports of the Boxer attacks seeped out of the beleaguered area and misinformation spread, like this headline in the New York Times on July 30: “Wave of Massacre Spreads over China. All Missionaries and Converts Being Exterminated. Priests Horribly Tortured. Wrapped in Kerosene-Soaked Cotton and Roasted to Death.”

In this same horrified mode, the July 28 cover of Harper’s Weekly—a publication that carried the subtitle “A Journal of Civilization”—depicted demonic Boxers brandishing primitive weapons, carrying severed heads on pikes, and trampling a child wrapped in the American flag. Uncle Sam and President McKinley countered the assault under another American flag on which was inscribed “Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness under treaty rights.” The cartoon caption reflected America’s self-image as a reluctant civilizer: “Is This Imperialism? No blow has been struck except for liberty and humanity, and none will be.”

|

|

|

|

“Is this Imperialism?

‘No blow has been struck except for liberty and humanity, and none will be.’

—William McKinley”

Harper’s Weekly, July 28, 1900

Artist: W. A. Rogers

Source: Widener Library, Harvard University

[cb70-014_harpers1900_07_v2a_012]

As the caption indicates, this cover illustration dismisses charges of imperialism that critics directed against American expansion at the turn of the century. Harper’s Weekly took pride in billing itself as “A Journal of Civilization.” The barbarians depicted here are Chinese Boxers who committed atrocities against Christian missionaries.

|

|

| |

After Allied forces were dispatched to relieve the sieges in Tianjin and Beijing, however, it did not take long before news reports and complementary visual commentary began to take note of barbaric conduct on both sides of the conflict. U.S. regiments were transported from the Philippines to join the Allied force. In an unprecedented alliance, the second expeditionary force was comprised of (from largest troop size to smallest) Japan, Russia, Great Britain, France, U.S., Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy. On China’s side, the Boxers were absorbed into the Qing government forces to fight the invaders. Allied troops departed Tianjin for Beijing on August 4.

Despite several victories in the battle for Tianjin, chaotic Chinese forces melted away before the Allied advance. With little opposition, Allied troops foraged for food and water in deserted villages, where the few who remained—often servants left to protect property—usually met with violence. Accusations of atrocities against civilians on the ten-day march to Beijing were made in first-hand accounts of the mission. Although protested by some commanders, no single approach prevailed among these competitive armies thrown together in a loose coalition. Newspapers carried pictures of corpses and stories of rape and plunder, notably in the wealthy merchant city of Tongzhou just before troops reached Beijing.

In 1901, occupation forces roamed the countryside to pillage, loot, and hunt for Boxers. Many peasants vaguely suspected of being Boxers were executed. The conduct of foreign troops in China was targeted in a searing cartoon by the French artist Théophile Steinlen. A laughing missionary in the lead, blood-soaked soldiers of the Allied forces tread on the bodies of women and children while carrying severed heads on a pike. The image appeared in the June 27, 1901 issue of L’Assiette au Beurre by Steinlen titled, “A Vision de Hugo, 1802–1902.” The full mural decries the bloodshed of colonial warfare in Turkey, China, and Africa.

|

|

|

| |

From the issue titled: “A Vision de Hugo, 1802–1902.”

L'Assiette au Beurre, February 26, 1902 (No. 47)

Artist: Théophile Steinlen

Source: Bibliothèque nationale de France

Duke University, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library

[cb72-245_1902_26Feb_pg05_HugoIssueBySteinlen_lassiette_au_beurre]

This special issue illustrated by Théophile Steinlen comprises a particularly gruesome mural depicting the bloodshed of contemporary colonial wars in Turkey, China, and Africa. The scene above turns the tables on the Harper’s Weekly cover (above) and accuses foreign troops and missionaries of atrocities during the Boxer Uprising in China.

|

|

|

Who is the Barbarian?

Juxtaposing the shocking Chinese barbarity depicted on the Harper’s Weekly cover with the equally shocking barbarity of Steinlen’s depiction of Allied atrocities in China gives rise to the question: who is the barbarian? Severed heads. Slaughtered infants. At first glance, the two mirror-image renderings could be part of the same picture.

|

|

|

Harper’s Weekly, July 28, 1900 (detail) Harper’s Weekly, July 28, 1900 (detail) |

L'Assiette au Beurre, Feb. 26, 1902 (detail) L'Assiette au Beurre, Feb. 26, 1902 (detail) |

|

| |

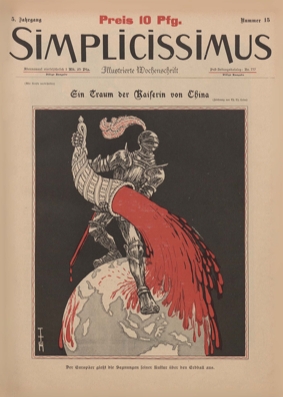

Eighteen months before Steinlen’s disturbing “mural,” another German artist, Thomas Theodor Heine, published a similarly blood-soaked rendering of the barbarities perpetuated abroad by Western military forces. Heine used the pages of Simplicissimus to denounce the atrocious conduct of Prussian troops during the Allied intervention in China, where the German forces obviously took to heart Wilhelm II’s exhortation to show no mercy. Heine provided Simplicissimus with what has become a justly famous image: an armed knight, representing the West, pours a torrent of blood over Asia, while his sword drips blood on Africa. Titled “Dream of the Empress of China,” the dream is an obvious nightmare, as the sardonic sub-caption makes clear. “Europeans,” this reads, “Pour the Blessings of Their Culture over the Globe.”

|

|

“Der Traum der Kaiserin von China”

(The Dream of the Empress of China)

Simplicissimus, July 3, 1900

Artist: Thomas Theodor Heine

Source: The Weimar Classics Foundation

[cb80-010_Simplicissimus_July3_1900]

“Der Europäer giesst die Segnungen seiner Kultur über den Erdball aus.”

(The Europeans pour the blessings of its culture over the globe.)

The satirical weekly, Simplicissimus, flourished from 1896 to 1967 with a hiatus from 1944 to 1954.

[Click here to view complete issue]

|

|

| |

“Think It Over: All this for politics—is civilization advancing?”

In the United States, the most famous counter-voice to Kipling and his “white man’s burden” rhetoric was the writer Mark Twain. The U.S. conquest of the Philippines, coupled with the multi-nation “Boxer intervention” in China, prompted Twain to become an outspoken critic of America plunging into what he denounced as the “European Game” of overseas expansion.

Twain’s most celebrated anti-imperialist essay, “To the Person Sitting in Darkness,” was published in the February, 1901 issue of the North American Review. His biblical title, which came from Matthew 4:16 (“The people who sat in darkness have seen a great light”), picked up on many pro-imperialist themes of the times. The language obviously resonated with the Kipling-esque imagery of white men bringing enlightenment to “new-caught sullen peoples, half-devil and half-child.” People of darkness was, moreover, a perception that missionaries (whom Twain excoriated) routinely applied to the “heathen” natives of non-Christian lands. As the cartoon record of these turn-of-the-century years repeatedly demonstrates, moreover, it was taken for granted by the imperialists that the people on whom they were bestowing the light of civilization were literally—and often grotesquely—of various shades of darker complexion.

“To the Person Sitting in Darkness” addressed Great Britain’s Boer War as well as the Philippine conquest and Boxer intervention. As Twain saw it, the U.S. war against the nascent Philippine Republic amounted to little more than mimicry of Britain’s bloody war of conquest in South Africa. Turning to China, his stinging indictment extended beyond the two Anglo powers to target the Kaiser’s Germany plus Tsarist Russia and France.

Beyond flat-out aggression and repression, the common thread that linked the imperialist powers, in Twain’s critique, was the hypocrisy of expansionist rhetoric about “Civilization and Progress.” (He itemized the virtues that supposedly animated this white man’s burden as “Love, Justice, Gentleness, Christianity, Protection of the Weak, Temperance, Law and Order, Liberty, Equality, Honorable Dealing, Mercy, and Education.”) The February 1901 essay opens with the satirical observation that: Extending the Blessings of Civilization to our Brother who Sits in Darkness has been a good trade and has paid well, on the whole; and there is money in it yet, if carefully worked—but not enough, in my judgement, to make any considerable risk advisable.

The noble rhetoric that buttressed overseas expansion, as Twain presented it, was largely for “Home Consumption,” and stood in sharp contrast to “the Actual Thing that the Customer Sitting in Darkness buys with his blood and tears and land and liberty.” Where “the Philippine temptation” in particular was concerned, he cited press reports of atrocities by American troops. There should be no problem designing a flag for the conquered Philippines, he opined in drawing his biting essay to a close: “we can have just our usual flag, with the white stripes painted black and the stars replaced by the skull and cross-bones.”

Around 1904 or 1905—in another impassioned response to the American war in the Philippines (which officially ended in 1902 but in practice dragged on for many years thereafter)—Twain penned a short essay titled “The War Prayer.” The essay is now regarded as an exemplary indictment of blind patriotism coupled with religious fanaticism. At the time, however, Twain’s family, acquaintances, and publisher feared the piece would be denounced as both unpatriotic and sacrilegious, and urged him not to publish it. Twain went along, partly out of concern for his family, and “The War Prayer” was not published until 1916, six years after his death.

“The War Prayer” begins with a preacher praising the nation’s just and holy war, and leading his congregation in praying for victory. It ends with a stranger entering the church and delivering a devastating description of the carnage experienced by invaded countries. Given the fact that Twain was famous and widely admired for his outspokenness, it is especially disconcerting to learn that he and his close supporters concluded that challenging the mystique of “civilization and progress” in such stark terms was not feasible given the political and religious fervor of the times.

At the same time, however, the suppression of “The War Prayer” helps highlight the courage and critical edge that many political cartoonists brought to the very same subject of spreading death and destruction in the name of civilization and progress. Indeed, the visual record was, in its unique way, more powerful—more literally graphic—than words alone could ever be.

As early as mid 1899, for example, Life called attention to the staggering death count among Filipinos with a cartoon titled “The Harvest in the Philippines.” It is now estimated that, all told, between 12,000 and 20,000 Filipino military perished in this conflict, as opposed to 4,165 killed on the U.S. side. Estimates of civilian fatalities, on the other hand, range from 200,000 to possibly well over a million. In “The Harvest in the Philippines,” Uncle Sam stands, armed to the hilt, gazing at the viewer with a field of Filipino corpses lined up in rows behind him and stretching back as far as the eye can see. The caption reference to “harvest” surely carried multiple meaning to many of Life’s American readers. It evoked both the fact that the bulk of the U.S. force was made up of units from the Midwestern states. And, more subtly yet, it reflected the shift from the nation’s agrarian roots toward global engagement.

|

|

|

|

“The Harvest in the Philippines”

Life, July 6, 1899

Artist: Frederick Thompson Richards

[cb91-313_1899_July6_Life]

In mid 1899, Life published this chilling view of the war in the Philippines that was to drag on for several more years. Uncle Sam, armed and dangerous, cocks an eyebrow as he displays his handiwork: countless dead Filipino soldiers laid out in rows.

|

|

| |

A year later, Judge magazine published a two-page cartoon by Victor Gillam that sets the contemporary “civilization versus barbarism” debate against a grand panorama of historical carnage. The caption reads “Think It Over”—a phrase that also appeared later in Mark Twain’s “To the Person Sitting in Darkness” essay. Gillam’s sub-caption is “All this for politics—is civilization advancing?”

Contemporary wars in the Philippines and Transvaal (the Boer War) comprise the foreground of the “Think It Over” battlefield. Close behind them lie corpses from the “Franco-Prussian War,” “Russia and Turkey,” “Napoleon and Austria.” Far off in the distance, with labels reading “Roman Wars” and “Alexandria,” the artists carries his viewers back to ancient times, when the civilization myth first emerged to mask the brutal realities of politically-motivated conflicts.

|

|

|

|

“Think It Over.

All this for politics—is civilization advancing?”

Judge, February 3, 1900

Artist: Victor Gillam

Source: Widener Library, Harvard University

[cb82-016_judge_1900_007]

The barbarity of imperial war is displayed on a battlefield littered with dead soldiers of many nationalities that stretches from contemporary wars—here, the “Philippines” and “Transvaal” (Boer War)—back through time to “Roman Wars.” The sub-caption of this 1900 Judge cartoon once again asks the disturbing question: “is civilization advancing?”

|

|

| |

In September 1901, the French artist Jean Veber used the pages of L’Assiette au Beurre to call attention to one of the often-forgotten ironies of the mystique of “the white man’s burden.” His cartoon, depicting a vast field of flat stone grave markers, carried the simple caption “United Kingdom” (Le Royaume-Uni).

A scrawny female figure in the background appears to be a skull-faced depiction of Britannia, grown thin and solitary through endless pursuit of war. The full sardonic irony of the rendering, however, resides in the dead occupants of the graves. All are erstwhile British soldiers. Their diverse identities, however, reflect the global reach and ethnic diversity of the British empire—and the extent to which England relied on colonial subjects to fight its imperialist wars. Thus, under the &lldquo;Here lies” (Hic jacet) on each gravestone, we see generic names coupled with places of origin extending from England to Scotland, Ireland, New Zealand, Canada, Australia, Gibraltar, India, Ceylon, and Egypt.

|

|

|

|

“Le Royaume-Uni”

(“United Kingdom”)

L’Assiette au Beurre, September 28, 1901

Artist: Jean Veber

Source: Bibliothèque nationale de France

[cb90-210_1901_Sept28_Transvaal_pg22]

In this cartoon from the French special issue on concentration camps in the Boer War, a gaunt Britannia is the only living creature in a vast graveyard for dead British soldiers. Generic names on the gravestones are coupled with places of origin, including England, Scotland, Ireland, New Zealand, Canada, Australia, Gibraltar, India, Ceylon, and Egypt, indicating the diversity of those recruited to fight and die for the British Empire. This military dimension of the multi-ethnic “United Kingdom” is often forgotten. (The artist signed his name on the grave on the lower right.)

[Click to view complete issue]

|

|

| |

The wars undertaken in the name of “Civilization and Progress” were more savage, tortuous, and contradictory than is often recognized. And the political cartoons of the time—subjective, emotional, ideological, highly politicized and at the same time, politically diversified—convey this complexity with unparalleled sophistication and intensity.

It is all too easy to assume that Americans, English, and others on the home front could not see what their nations were doing overseas. The turn-of-the-century visual record tells us otherwise.

|

|

|