| |

“THE WHITE MAN’S BURDEN”

During the last decade of the 19th century, the antagonistic relationship between Great Britain and the United States—rooted in colonial rebellion and heightened in territorial conflicts like the War of 1812—grew into a sympathetic partnership. In the U.S., the 1860s Civil War generated suspicion that neutral Britain covertly supported the Confederacy. Postwar industrialization and the introduction of new commodities such as steel and electricity gradually transformed the agrarian nation. As the American West was absorbed and the continent consolidated, the mandate of “Manifest Destiny” shifted from territorial to commercial expansion beyond contiguous borders.

As a long-established world empire, Great Britain held sway over some 12 million square miles and a quarter of the world’s population. Backed by the formidable Royal Navy, Britain could maintain a policy of “splendid isolation” independent of European alliances for much of the century. But by the 1890s, emerging industrial powerhouses like the U.S. and Germany reduced Britain’s industrial dominance. As Britain stepped up financial industries, shipping, and insurance to make up the deficit, global sea power took on additional significance. New commodities also meant advances in weaponry that might give neighboring countries—in particular, Germany—the potential to strike Britain. To maintain its position in the international balance of power, Britain needed allies. Relatively free from European rivalries and well situated to become a transoceanic partner, the U.S. was courted for the role.

Beyond commercial and military prowess, the two nations formed a natural brotherhood within attitudes later labeled as social Darwinism. When applied to people and cultures, the “survival of the fittest” doctrine gave wealthy, technologically-advanced countries not only the right to dominate “backward” nations, but an imperative and duty to bring them into the modern world. The belief in racial/cultural superiority that fueled the British empire embraced the U.S. in Anglo-Saxonism based on common heritage and language. In the U.S., despite spirited resistance from Anglophobic Irish immigrants and anti-imperialist leagues, overseas military campaigns gradually gained public support.

The burgeoning mass media helped promote jingoistic foreign policies by printing disparaging depictions of barbarous-looking natives from countries “benevolently assimilated” by the U.S. A brash Uncle Sam was shown coming under the wing of the older, more experienced empire builder, John Bull. Uncle Sam was portrayed both with youthful energy and as a paternal older figure straining to follow in John Bull’s footsteps as he took up the “White Man’s Burden.”

“After Many Years”: The Great Rapprochement

“The Great Rapprochement” describes a shift in the relationship of the U.S. and Great Britain that, in the 1890s, moved from animosity and suspicion to friendship and cooperation.

In an 1898 two-page spread in Puck, female symbols of the two nations, Columbia and Britannia, meet as mother and daughter to celebrate their reunion “After Many Years.” Wearing archaic breastplates and helmets, with trident and sword, these outsized, archetypal crusaders helm modern warships. The conspicuously larger size of Britannia’s big guns in Puck’s cartoon reflects England’s leading role in imperial conquest.

Contemporary conflicts are spelled out over dark clouds. Looming on the left, the “Eastern Question” refers to the long-standing British confrontation with Russia in the Balkans that would soon extend to conflict over Britain’s “Cape to Cairo” strategy in Africa. The Battle of Omdurman in September 1898—in which British forces retook the Sudan using Maxim machine guns to inflict disproportionate casualties on native Mahdi forces—was followed almost immediately by the “Fashoda Crisis” with France, in which the British asserted their control of territory around the upper Nile.

Written over the battle clouds on the right, the “Spanish-American War” would have inspired the depiction of Columbia as an emerging military power. On May 1, the U.S. Navy scored its first major victory in foreign waters—far from assured given the weakness of the American fleet at the time—by defeating Spanish warships defending their longtime Pacific colony in the Battle of Manila Bay.

|

|

|

|

“After Many Years.

Britannia—Daughter!

Columbia—Mother!”

Puck, June 15, 1898

Artist: Louis Dalrymple

Source: Library of Congress [view]

[cb03-020_puck_1898_June15_AfterManyYears_loc]

In this 1898 cartoon, Britannia (Great Britain) welcomes Columbia (the United States) as an estranged daughter and new imperialist partner. The U.S. entered the elite group of world powers with victories in the “Spanish-American War” (written in the clouds over the naval battle on the right). In the storm clouds on the left, the “Eastern Question” looms.

|

|

| |

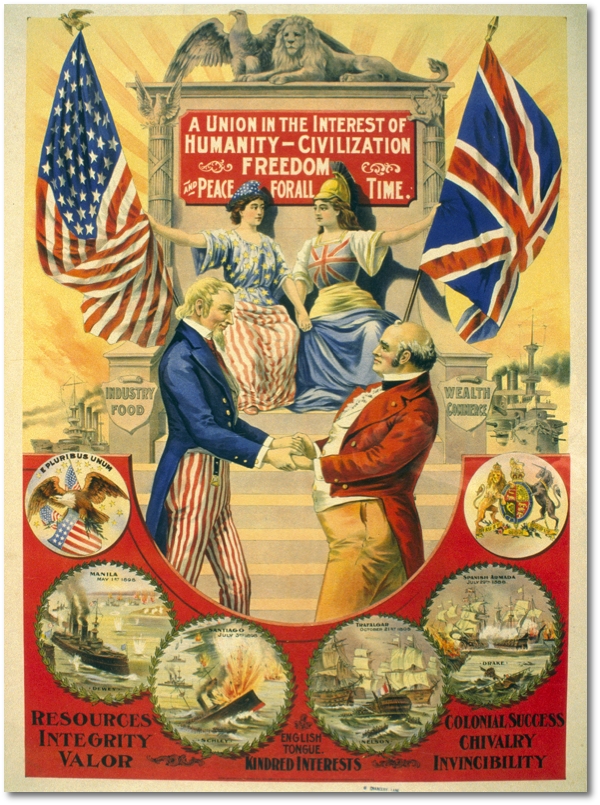

A poster headlined “A Union in the Interest of Humanity – Civilization, Freedom and Peace for all Time,” probably also dating from 1898, celebrated the rapprochement between the United States and Great Britain with particularly dense detail. In this rendering, progress—economic, technological, and cultural—is spread through global military aggression. The rays of the sun shine over Uncle Sam and John Bull, who clasp hands in a renewed Anglo-American alliance of “Kindred Interests” rooted in the “English Tongue.” Warships on the horizon ground their mission in naval power. Britain, the more powerful military partner, shows celebrated victories over the Spanish Armada in 1588 and over the French and Spanish navies at Trafalgar in 1805. The U.S. is newly victorious in 1898 naval victories over the Spanish at Manila and Santiago de Cuba. “Colonial success” is equated with “chivalry” and “invincibility.”

|

|

| |

| |

| |

“A Union in the Interest of Humanity – Civilization

Freedom and Peace for all Time.”

ca. 1898, Donaldson Litho Co.

Source: Library of Congress [view]

[cb27-004_1900_Judge_BackUp_000016]

This ca. 1898 poster promotes the U.S.-British rapprochement as “A Union in the Interest of Humanity – Civilization, Freedom and Peace for All Time.” Multiple representations symbolize the two Anglo nations: national symbols (the eagle and lion); flags (the Stars and Stripes and Union Jack); female personifications (Columbia and Britannia); male personifications (Uncle Sam and John Bull); and national coats of arms (eagle and shield for America; lion, unicorn, crown, and shield for Great Britain).

|

|

| |

“A Rival Who Has Come to Stay”: Naval Power

In the final years of the Civil War, U.S. naval power was second only to the great seafaring empire of Great Britain. The regular army was dissolved after the war and the ironclad warships gradually fell into disrepair. Few new vessels were commissioned until the 1880s when the first battleships were built, U.S.S. Texas and U.S.S. Maine. Militarily beneath notice by the major European powers, and able to resolve conflicts with Britain in the Western Hemisphere diplomatically, there was little pressure for a strong military in the U.S. With minimal military expenditures, the U.S. economy grew rapidly.

By the 1890s, the U.S. began to revitalize both its commercial and naval fleets. Partnership with Great Britain brought the advantage of shared technology to the U.S., but the new American-made ships represented competition for the British shipbuilding industry. In an 1895 Puck cartoon, “A Rival Who Has Come to Stay,” John Bull gapes while Uncle Sam proudly displays his prowess as “Uncle Sam the Ship Builder.” The U.S. Navy moved up from twelfth to fifth place in the world.

|

|

|

|

“A Rival Who Has Come to Stay.

John Bull – Good 'evins! – wotever 'll become of my ship-building monopoly, if that there Yankee is going to turn out boats like that right along?”

Puck, July 24, 1895

Artist: Louis Dalrymple

Source: Library of Congress [view]

[cb05-129_1895_July24_ShipBuilder_Puck_29027u_loc]

|

|

|

Left: John Bull gapes at a new American steamer. The sign on the shores of England reads, "John Bull – The old reliable ship builder since 1861. Ships for American commerce a speciality.” Left: John Bull gapes at a new American steamer. The sign on the shores of England reads, "John Bull – The old reliable ship builder since 1861. Ships for American commerce a speciality.”

|

Right: Uncle Sam proudly displays his new steamship and a sign that reads, "Uncle Sam the ship builder re-established with great success in 1893. American ships for American commerce!!" Right: Uncle Sam proudly displays his new steamship and a sign that reads, "Uncle Sam the ship builder re-established with great success in 1893. American ships for American commerce!!" |

|

| |

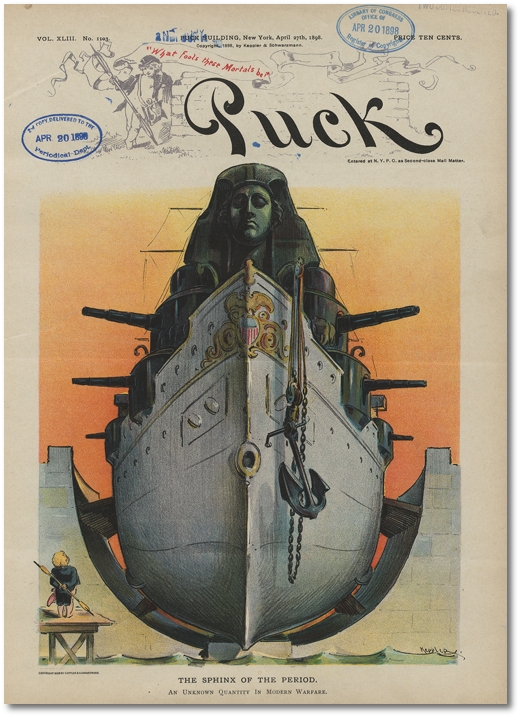

The test of U.S. naval power came with the Spanish-American War. A pair of 1898 graphics offer “before and after” snapshots related to two major events.

On February 15, 1898, the battleship U.S.S. Maine exploded and sank in the harbor at Havana. The Maine had been dispatched to Cuba to support an indigenous insurrection against Spain. The cause of the explosion is still undetermined. In all likelihood, it was an internal malfunction, but many Americans blamed the Spanish and rallied behind the slogan “Remember the Maine, to Hell with Spain.” The United States declared war on Spain on April 20, and the fury kindled by the sinking of the Maine was appeased by a great U.S. naval victory on the other side of the world two and a half months later. On May 1—a month before the celebratory second magazine cover reproduced here was published—Commodore George Dewey destroyed a Spanish fleet in Manila Bay in the Philippines.

Published in April 27, 1898, the first cartoon calls the monumental warship “The Sphinx of the Period: an unknown quantity in modern warfare.”

|

|

|

| |

“The Sphinx of the Period.

An Unknown Quantity in Modern Warfare.”

Puck, April 27, 1898

Artist: Udo Keppler

Source: Library of Congress [view]

[cb06-108_1898_April27_puck_Sphinx_28695u_loc]

|

|

| |

About a month later, a June 1 graphic picks up on the Sphinx metaphor and declares “The American Battle-Ship is No Longer an Unknown Quantity.” A pugnacious sailor and sweeping U.S. flag have replaced the inscrutable sphinx; guns are smoking, the Spanish fleet lies sunken below.

|

|

|

| |

“The Modern Sphinx has Spoken.

The American Battle-Ship is No Longer an Unknown Quantity.”

Puck, June 1, 1898

Artist: Louis Dalrymple

U.S. Library of Congress [view]

[cb07-109_1898_June1_puck_sphinx2_28705u]

|

|

| |

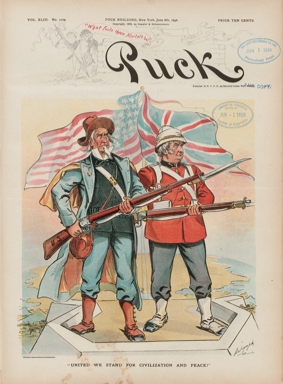

“United We Stand for Civilization and Peace”: the Anglo-Saxon Globe

By the end of 1898, a succession of U.S. military successes and territorial acquisitions reinforced the image of the United States standing side by side with Great Britain in bringing “civilization and peace” to the world. Commodore Dewey’s victory in Manila Bay in May not only paved the way for U.S. conquest of the Philippines, but also provided a valuable naval base for U.S. fleets in the Pacific. (This coincided with the annexation of Hawaii as a U.S. territory in congressional votes in June and July of the same year.) Simultaneously, the war against Spain in Cuba and the Caribbean saw the U.S. seizure of Cuba’s Guantanamo Bay in June, giving the U.S. a naval base retained into the 21st century. This was followed by the invasion and takeover of Puerto Rico. Looming just ahead for the two Anglo nations were turbulence and intervention in such widely dispersed places as Samoa, China, and Africa.

Puck’s cover for June 8, 1898, celebrated this new Anglo-Saxon solidarity and sense of mission with an illustration of two resolute soldiers standing with fixed bayonets on a parapet and overlooking the globe. Their uniforms are oddly reminiscent of the Revolutionary War that had seen them as bitter adversaries a little more than a century earlier. The caption at their feet exclaims “United We Stand for Civilization and Peace!”

|

|

"United We Stand for Civilization

and Peace!"

Puck, June 8, 1898

Artist: Louis Dalrymple

Source: Library of Congress [view]

[cb08-030_1898_8June_puck_united_28707u_loc]

Uncle Sam and John Bull, as fellow soldiers, survey the globe from a parapet. The caption applies the motto “united we stand” to the Anglo-Saxon brotherhood spreading Western civilization abroad. |

|

| |

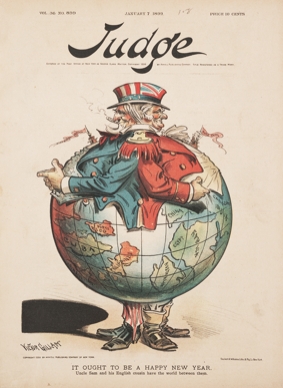

The weekly magazine Judge, a rival to Puck that was published from 1881 to 1947, opened 1899 with a barbed rendering of the Anglo nations gorging on the globe. “It ought to be a Happy New Year,” the caption reads. “Uncle Sam and his English cousin have the world between them.” Here, the United States has ingested Cuba, “Porto” Rico, Hawaii, and the Philippines. Britain is digesting China, Egypt, Australia, Africa, Canada, and India. Warships steam over the horizon of their chests flying banners of great waterways that would ideally open the world to commerce—“Suez Canal” (completed in 1869) and “Nicaragua Canal” (projected through Nicaragua to link the Caribbean and Pacific oceans—an undertaking later transferred to Panama).

|

|

“It Ought to be a Happy New Year.

Uncle Sam and his English cousin have the world between them”

Judge, January 7, 1899

Artist: Victor Gillam

Source: CGACGA - The Ohio State University Billy Ireland Cartoon

Library & Museum [view]

[cb09-140_1899_Jan7_Judge_d_10385_osu]

John Bull, whose portliness stood for prosperity, has joined with Uncle Sam to swallow the globe. The boats crossing their chests, labeled “Suez Canal” and “Nicaragua Canal,” show the importance of efficient naval and shipping routes through their “distended” realms. The countries have been jumbled to align them with American or British imperialistic interests. |

|

| |

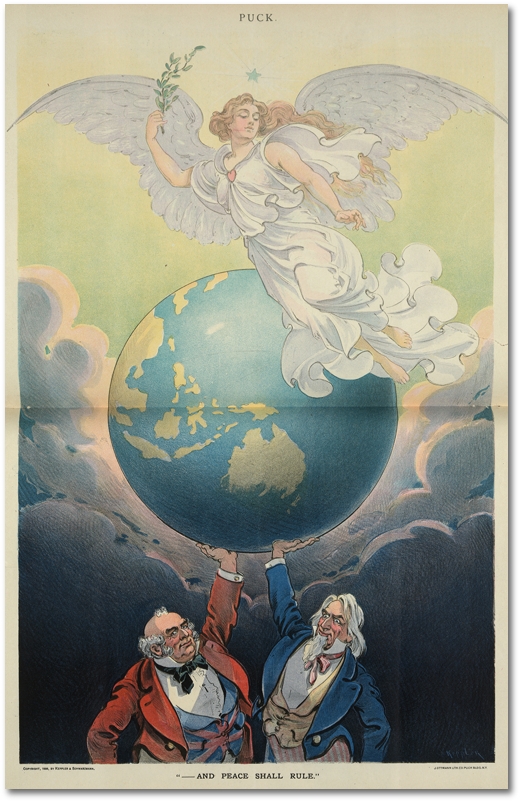

Udo Keppler, a Puck cartoonist who was still in his twenties at the time, was more benign in his rendering of the great rapprochement. A cartoon published in May, 1899 over the caption “—And Peace Shall Rule” offered a female angel of peace flying over a globe (turned to Asia and the Pacific) hoisted by John Bull and Uncle Sam.

|

|

|

| |

“—And Peace Shall Rule”

Puck, May 3,1899

Artist: Udo Keppler

Source: Library of Congress [view]

[cb10-101_puck_1899_May3_Peace_28594u]

John Bull and Uncle Sam lift the globe, turned toward Asia and the Pacific, to the heavens. The angel of peace and caption suggest that their joint strength will bring about world peace.

|

|

| |

From the high to the low, by 1901 the collaboration between the two Anglo nations held a different fate for the globe. In the French cartoon “Leur rêve” (Their dream), the globe is portrayed as a victim carried on a stretcher. The two allies had been embroiled in lengthy wars with costly and devastating effects on the populations in Africa and Asia.

|

|

|

|

“Leur rêve.”

Translation: “Their dream.”

L’Assiette au Beurre, June 27, 1901

Artist: Théophile Steinlen

Source: Bibliothèque nationale de France

[cb20-226_1901_June27_212-213]

This French cartoon eschews the romantic presentation in the preceding Puck graphic and casts a far more cynical eye on Anglo-American expansion as fundamentally a matter of conquest.

[view complete issue]

|

|

| |

In the centerfold of the August 16, 1899 issue of Puck, the not-so-cynical Keppler extended his feminization of global power politics to other great nations including a new arrival on the scene: Japan. Following its victory over China in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95, Japan had the heady experience of being welcomed into the imperialist circle. Keppler rendered this as “Japan Makes her Début Under Columbia’s Auspices,” with Columbia, Britannia, and a geisha-like Japan at the center of the scene. Seated around them (left to right) are a feminized Russia, Turkey, Italy, Austria, Spain, and France. A tiny female “China” peers at the scene from behind a wall.

In Library of Congress notes on this image, the seated figure on the left is identified as Minerva—the Roman goddess of wisdom, arts, and commerce, which would be a perfectly mythologized rendering of the mystique of Western “civilization.” Instead, however, it is recognizable as Germania (Germany), personified with her reddish-blond hair, black-white-red dress mirroring the flag of the German empire, and shield bearing an eagle with outspread wings.

|

|

|

|

“Japan Makes her Début Under Columbia’s Auspices.”

Puck, August 16, 1899

Artist: Udo Keppler

Source: Library of Congress

[view]

[cb21-112_puck_1899_Aug16_JapanDebut_28532u]

Japan is introduced in this 1899 cartoon as the lone Asian nation in the imperialist circle of world powers. Having defeated China in 1894–95, Japan is presented by Columbia (the U.S.) to her closest ally, Britannia (Great Britain). The feminine representations of imperial nations pictured here include Russia, Turkey, Italy, Austria, Spain, and France. China peeps over the wall. The unidentified figure on the left is Germania (Germany), personified with her reddish-blond hair, black-white-red dress mirroring the flag of the German empire, and shield bearing an eagle with outspread wings.

|

|

| |

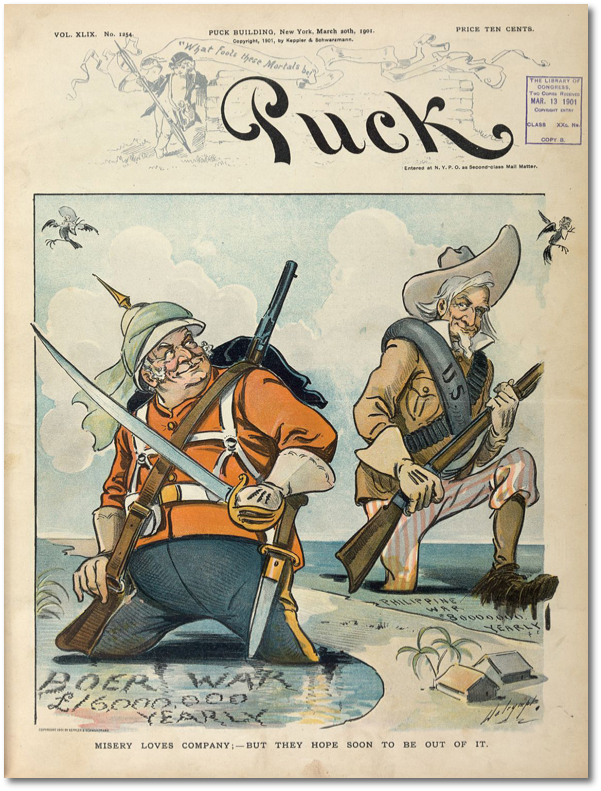

“Misery Loves Company”: Parallel Colonial Wars (1899-1902)

From 1899 to 1902, the U.S. and Great Britain each became mired in colonial wars that were more vicious and long-lasting than expected. Having purchased the Philippines from Spain per the Treaty of Paris for $20 million, the Americans then had to fight Filipino resisters to “benevolent assimilation.” The Philippine-American War dragged on with a large number of Filipino fatalities, shocking Americans unused to foreign wars. The war was declared over by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1902 but continued in parts of the country until 1913.

At the same time, Britain was fighting the Anglo-Boer War in South Africa. The war with the Boers (who were ethnically Dutch and Afrikaans-speaking) took place in the South African Republic (Transvaal) and Orange Free State. When rich tracts of gold were discovered, an influx of large numbers of British immigrants threatened to overturn Boer rule over these republics. Britain stepped in to defend the rights of the immigrants, known as uitlanders (foreigners) to the Boers. The larger objective, to gain control of the Boer territories, was part of Britain’s colonial scheme for “Cape to Cairo” hegemony in Africa. The campaign met with fierce resistance and saw the introduction of concentration camps as an extreme maneuver against the Boer defenders.

Despite public neutrality, the U.S. and Britain covertly supported each other. While the European powers favored Spain in the Spanish-American War, for example, neutral Britain backed the U.S. During the 1898 Battle of Manila Bay, British ships quietly reenforced the untried U.S. navy by blocking a squadron of eight German ships positioned to take advantage of the situation. Presence of a German fleet lent evidence to one of the justifications the U.S. gave for war with Spain, that is, to protect the Philippines from takeover by a rival major power. The U.S. policy of “benevolent neutrality” supported Britain in the Boer War with large war loans, exports of military supplies, and diplomatic assistance for British POWs. In addition, the U.S. ignored human rights violations in the use of concentration camps.

The human and financial cost of these extended conflicts was large. A 1901 Puck cover, “Misery Loves Company...,” depicts John Bull and Uncle Sam mired in colonial wars at a steep price: "Boer War £16,000,000 yearly" and "Philippine War $80,000,000 yearly." Anti-imperialist movements targeted the human rights violations in both the Philippines and Transvaal in their protests.

|

|

| |

| |

| |

“Misery Loves Company; — but they hope soon to be out of it”

Puck, March 20, 1901

Artist: Louis Dalrymple

Source: Theodore Roosevelt Center at Dickinson State University [view]

[cb27-004_1900_Judge_BackUp_000016]

By 1901, John Bull and Uncle Sam were bogged down in prolonged overseas wars at a cost, here, the "Philippine War $80,000,000 yearly" and the "Boer War £16,000,000 yearly." Yet, the protagonists exchange encouraging looks, revealing the covert support behind their positions of “benevolent neutrality.”

|

|

| |

Unlike Puck and Judge, Life was often highly critical of U.S. overseas expansion. Life’s black-and-white January 4, 1900 cover welcomed the new millennium by illustrating “The Anglo-Saxon Christmas 1899.” John Bull and Uncle Sam are positioned within a holiday wreath, machine guns pointing out in both directions. The caption is ominous: “War on Earth. Good Will to Nobody.”

|

|

“The Anglo-Saxon Christmas 1899

War on Earth. Good Will to Nobody.”

Life, January 4, 1900

Artist: unidentified

Source: Widener Library,

Harvard University

[cb23-133_1900_Jan4_life1900v2_001_widener]

John Bull and Uncle Sam celebrate “The Anglo-Saxon Christmas” of 1899 together, manning machine guns from within a holiday wreath. |

|

| |

The Poet, the President & “The White Man’s Burden”

Rudyard Kipling’s poem that begins with the line “Take up the White Man’s burden—” was published in the United States in the February, 1899 issue of McClure’s Magazine, as the American war against the First Philippine Republic began to escalate. The phrase became a trope in articles and graphics dealing with imperialism and the advancement of Western “civilization” against barbarians—or as the poem put it, “Your new-caught sullen peoples, Half devil and half child.”

The poem acknowledged the thanklessness of a task rewarded with “The blame of those ye better, The hate of those ye guard—” and sentimentalized the “savage wars of peace” as self-sacrificial crusades undertaken for the greater good. Kipling offered moral justification for the bloody war the U.S. was fighting to suppress the independent Philippine regime following Spanish rule. “The White Man’s Burden” was used by both pro- and anti-imperialist factions.

At the core of the “White Man’s Burden” is a reluctant civilizer who takes up arms for “the purpose of relieving grievous wrongs,” in the words of President William McKinley. In his 1898 notes for the Treaty of Paris—which ended the Spanish-American War with Spain surrendering Cuba and ceding territories including Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines—McKinley made a prototypical statement of the civilizer’s responsibilities in the kind of rhetoric still used today:

We took up arms only in obedience to the dictates of humanity and in the fulfillment of high public and moral obligations. We had no design of aggrandizement and no ambition of conquest.

Regarding the Philippines in particular, he continues:...without any desire or design on our part, the war has brought us new duties and responsibilities which we must meet and discharge as becomes a great nation on whose growth and career from the beginning the ruler of nations has plainly written the high command and pledge of civilization.

McKinley also mentions profit, free trade, and the open door in Asia:Incidental to our tenure in the Philippines is the commercial opportunity to which American statesmanship cannot be indifferent. It is just to use every legitimate means for the enlargement of American trade; but we seek no advantages in the Orient which are not common to all. Asking only the open door for ourselves, we are ready to accord the open door to others.

An exceptionally vivid cartoon version of Kipling’s message titled “The White Man’s Burden (Apologies to Rudyard Kipling)” was published in Judge on April 1, 1899. “Barbarism” lies at the base of the mountain to be climbed by Uncle Sam and John Bull—with “civilization” far off at the hoped-for end of the journey, where a glowing figure proffers “education” and “liberty.” The fifth stanza of Kipling’s poem refers to an ascent toward the light:

The cry of hosts ye humour

(Ah, slowly!) toward the light:—

"Why brought he us from bondage,

Our loved Egyptian night?" Barbarism’s companion attributes of backwardness, spelled out on the boulders underfoot, include oppression, brutality, vice, cannibalism, slavery, and cruelty. Britain leads the way in this harsh rendering, shouldering the burden of “China,” “India,” “Egypt,” and “Soudan.” The United States staggers behind carrying grotesque racist caricatures labeled “Filipino,” “Porto Rico,” “Cuba,” “Samoa,” and “Hawaii.”

The racism and contempt for non-Western others that undergirds Kipling’s famous poem—and the “civilizing mission” in general—is unmistakable here. At the same time, the distinction the artist draws between Britain’s burden and America’s is striking. America’s recent subjugated populations are savage, unruly, and rebellious—literally visually “half devil and half child,” as Kipling would have it. By contrast, with the exception of Sudan, the burden Britain bears reflects backward older cultures that look forward to “civilization” or back, condescendingly, at those people, cultures, and societies deemed even closer than they to “barbarism.” Both visually and textually, the “white man’s burden” was steeped in derision of non-white, non-Western, non-Christian others.

|

|

|

|

“The White Man’s Burden (Apologies to Rudyard Kipling)”

Judge, April 1, 1899

Artist: Victor Gillam

Source: CGACGA - The Ohio State University

Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum [view]

[cb25-141_1899_Judge_d_10386_osu]

The U.S. follows Britain’s imperial lead carrying people from “Barbarism” at the base of the hill to “Civilization” at its summit. In this blatantly racist rendering, America’s newly subjugated people appear far more primitive and barbaric than the older empire’s load.

|

|

| |

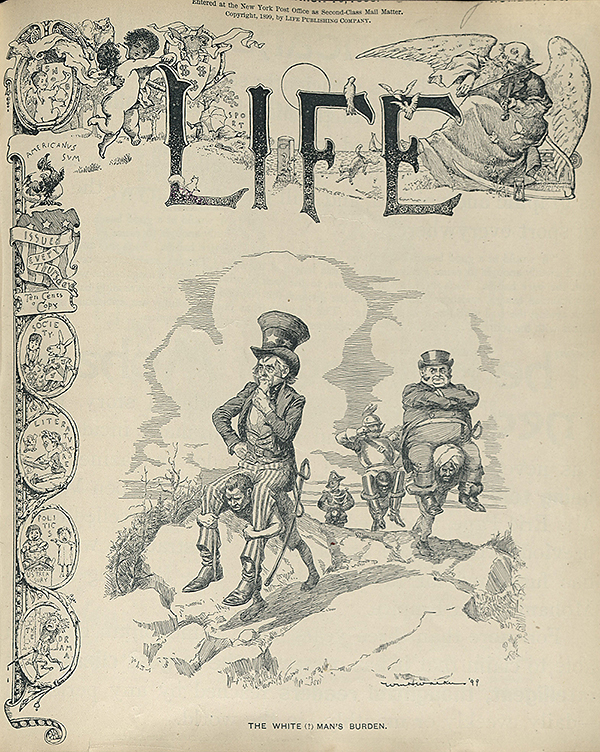

Shortly after Kipling’s poem appeared, the consistently anti-imperialist Life fired back with a decidedly different view of the white man’s burden on its March 16, 1899 cover: a cartoon that showed the foreign powers riding on the backs of their colonial subjects. The black-and-white drawing by William H. Walker captured the harsh reality behind the ideal of benevolent assimilation, depicting imperialists Uncle Sam, John Bull, Kaiser Wilhelm, and, coming into view, a figure that probably represents France, as burdens carried by vanquished non-white peoples. The addition of a question mark in the caption, “The White (?) Man’s Burden,” emphasized its hypocrisy. The U.S. appears to be carried by the Philippines, Great Britain by India, and Germany by Africa. Although Wilhelm II was famous for introducing the concept of a “yellow peril,” Germany’s major colonial possessions were in Africa.

|

|

|

|

“The White (?) Man’s Burden”

Illustration on the cover of Life, March 16, 1899

Author: William H. Walker

Source: William H. Walker Cartoon Collection, Princeton University Library [view]

[cb26-139_1899_March16_WllmHWalker_WhManB_LifeMag_Princeton]

A question mark was added to the phrase, “The White (?) Man’s Burden,” in the caption to this Life cover published shortly after Kipling’s poem. Imperialists Uncle Sam, John Bull, Kaiser Wilhelm, and, in the distance, probably France are borne on the backs of subjugated people in the Philippines, India, and Africa.

|

|

|

Walker's illustration appeared

on the

cover of Life with

the caption

“The White (?) Man’s Burden.”

[cb330_1899_March16_

WhiteManBurden_Widener_600w.jpg]

|  |

|